On the trail of Gideon Lewis-Kraus

by Mark ReynoldsIn his discursive and entertaining debut A Sense of Direction Gideon Lewis-Kraus challenges the boundaries of memoir and travelogue as he departs a life of lazy curiosity and stale hedonism in Berlin to embark on three distinct pilgrimages to examine how we may be defined by ritual, desire and purpose. Along the well-trodden trail of the Camino de Santiago across northern Spain with fellow writer Tom Bissell, on a solo circuit of 88 temples on the island of Shikoku, and in a rag-tag gathering in Ukraine at the tomb of a fairly obscure Hassidic mystic, Lewis-Kraus is an engagingly honest, funny and thoughtful guide to spiritualism, earthly endeavour, and the hardwired optimism and unreliability of the human family.

There’s an inference in the title that he was himself directionless until embarking on the pilgrimage journeys, but it’s quickly plain that he’s driven by a need to write, examine and interpret. So did he exaggerate his listlessness in Berlin in order to give the book structure?

“Yes, definitely!” he agrees. “There was a Colm Tóibín review in the Guardian that I really liked because he made this point that nobody else had made, which I’ve been waiting for somebody to make, that this is a little bit of an unreliable narrator – intentionally so – and that there are aspects that have been exaggerated to make certain points. I had been writing for years before I moved to Berlin, I’d written a bunch of stories for Harper’s, I’d reviewed books for the New York Times, and I moved to Berlin at least initially with a Fullbright scholarship; I had some institutional structure, even if a flimsy one, to be there. But I was also there to do a lot of other things: to speak good German, to meet young Europeans, I had a lot of aims and writing was just one of them. I never really intended to write about Berlin – if I had, I’d have taken better notes. But as I was writing about the Camino while en route, I realised that this was going to be enough material for some sort of book, and that I wanted to explore the concept of pilgrimage further – it was a concept I could hang another bunch of conversations on. And it was only when I sat down to write a book proposal and I had to frame why I had gone off on the Camino that I wrote about living in Berlin. It was only after I finished that proposal and the book was bought that then I thought, actually this is exactly the right way to frame the Camino, I’ll expand this into a short introduction. It ended up being a bit longer than I expected. I certainly felt at loose ends in Berlin, I didn’t always feel like I was doing the things that I wanted to be doing, but for the purposes of the narrative, to make the points I wanted to make, it seemed useful to play up my feelings of fecklessness, even if they weren’t strictly accurate, or had been a little bit magnified for the point of the book. One of the things I’ve done since this book is to figure out a way to continue channeling my restlessness into productive ventures. So these days I travel to work on reporting projects. It’s been a while since I’ve taken a vacation, but I travel constantly for work.”

One enduring image on the Camino, among the many colourful characters on that trail, is of a German father who has seemingly taken his two sons on a bonding trip, only to be constantly outpaced by them as they walk half a kilometre ahead lost in their headphones.

“It made me sad, actually, watching that happen. I felt this has got to mean so much to this father, and the kids have just shown up in the most frictional way. I think these kids will regret it at some point, that they had this opportunity and they had their headphones on the whole time. But I wasn’t judgmental… about halfway through my trip in Japan I started listening to music as I went along because it was otherwise unbearable. I went the first half as a kind of purist, and then I was very glad that I gave that up.”

Re-establishing a bond with his own father became an unexpected central theme to the book. It was only towards the end of the writing process that their reconciliation became a strong focus.

I mentioned off-handedly that my dad is a gay rabbi and we don’t have the easiest relationship, and my editor said, you know what, you’ve already done the Christian one and the Buddhist one, maybe you should find a Jewish one and take your dad along.”

“I had never planned to write about my father. Initially I had 150 pages about the Camino and I’d heard about this Japanese trip from people on the Camino which sounded really interesting and would give me a chance to work out further these ideas I had about what pilgrimage did and could mean. And I thought, OK, I’ve written half a book, and now I’ll go to Japan and write the other half, and I’ll do something with the fact that one is a line and the other is a circle. By that point I knew I was working on an actual book, and my book editor and I were talking over lunch and I mentioned off-handedly that my dad is a gay rabbi and we don’t have the easiest relationship. And she said, you know what, these things usually come in threes. You’ve already done the Christian one and the Buddhist one, maybe you should find a Jewish one and take your dad along. And I thought, that’s a terrible idea. I hadn’t had a successful trip with my dad in more than ten years, and I thought about the closeness of being with Tom on the Camino and thought, God, my dad and I would kill each other. But then, thinking it over, at that point the book had become about pilgrimage as pretext, and I thought it can serve as a pretext for adventure, it can serve as a pretext for an escape, for flight, so it serves pretty well as a pretext for conversation, especially because there’s this expectation that you’re going to rise to the occasion – necessarily it’s got a charged feeling, as something hovering outside of everyday life. Though still, there’s no way I’d be walking with him for more than a few days. Then I happened to read about this thing in Uman in Ukraine [a three-day pilgrimage to the tomb of Hassidic mystic Nachman of Breslov] and thought, oh, maybe we could actually do this, it’s a very short trip, it’s self-contained…”

He was also able to persuade his younger brother Micah to join them, counting on his greater capacity for peacemaking should things get uncomfortable (where the elder Lewis-Kraus admits to a tendency to harbour and nurture long-lasting grievances his brother, he says, can offend someone one minute, and the next be pipette-feeding their kittens).

“So I went on this trip with my dad and thought maybe something will come out of it, maybe it’ll be an epilogue or something. And then afterward I got on a train from Kiev to Berlin, and… I tend to resist romantic images of writing or metaphors, but this was the only time in my life that I’ve actually felt like I was in some kind of fugue state. I was on this train for 24 hours and I just sat there the whole time and I wrote 25,000 words – I think I slept for two hours – and I got to Berlin and I emailed the material to my editor right away, without having looked back at it. She wrote back and said this is great material, but your book cannot just take a hard swerve into memoir three-quarters of the way through, and now you’re going to have to find a way to drag back all this material through the rest of the book to make it all cohere. Then she said, wait a minute, didn’t you talk to your dad for the first time in two years when you were on the Camino? Then it was so interesting for me to revisit the first two chapters I’d written in the light of this subsequent conversation, and that was what made the book into a much more personal book than I’d ever set out to write. I thought I was going to write the book in two registers, in a sort of Paul Theroux picaresque travelogue register, and a more quasi-anthropological/philosophical register where I talk about Richard Turner’s ideas and those sorts of things, and then I ended up having to fit in this third register, the personal part, and figure out how to weave those three things together in a way that didn’t seem jarring.”

I ask if his dad had a crisis of faith when he came out; or is it not that tough to be a gay rabbi?

“No, there was no crisis of faith. I mean, he doesn’t like to take personal responsibility for things, so he loves to either credit or blame everything he can on his sexuality. So he thinks he lost a job because he came out, but that doesn’t explain why he lost a lot of other jobs. This is one of the things I have found and still find so frustrating, the way that he exploits his sexuality as this ‘get out of jail free’ card. So there wasn’t a crisis of faith. I mean I never thought of my dad as somebody who had an unusual amount of faith to begin with…”

So that’s not a prerequisite for a rabbi…?

“Well, Judaism emphasises practice over belief, right? Rarely is it ever prescribed what you have to believe, it’s just about what you have to do. So you don’t necessarily have to actually push the belief aspect of it all that far if you don’t want to. To some extent that’s what the book is about, how at least superficially obeying the rules, and having that kind of structure, is a way to remain internally free. One can think what one wants about how to interpret what’s going on, but you can be anchored in a practice while feeling flexible within that.”

With political tensions in Ukraine erupting the weekend before we meet, I’m curious to know how apparent the cultural and ethnic divisions in the country were during his visit.

“Well, our contact with Ukrainians in Uman was scant, because in Uman the Jews essentially displaced the Ukrainians, who had moved out into their friends’ apartments. But certainly when we travelled for a few days afterward, in Odessa and Kiev, you could see the extent to which the country is still divided between ethnic Russians and ethnic Ukrainians. We were mostly in the Ukrainians’ places, and it was certainly something that came up. I never would have predicted what’s happening now, but this seems to have much more to do with Putin than it does with the Ukrainians. I mean, look at what’s going on in Georgia. These breakaway republics that have so-called independence movements, most of those have just been planted by the Russians as a way to foment conflict and take territory away.”

On the two longer journeys Lewis-Kraus is in continuous conflict with John Brierley and David Moreton, authors of the two main guidebooks to the Camino and Shikoku. It’s a relationship he winningly describes as his ‘bat-shit guidebook-author complex’. Though at one point he is distraught when he discovers he has left the Moreton behind and has to backtrack to the previous temple stop to retrieve it.

“Mmm, terrible, terrible day… I think the conflict is because I take guidebooks really seriously. Obviously it’s a little bit different now that everybody has the internet, but to write a guide book is to assume an enormous amount of responsibility because you’re the one shaping somebody’s experience of a place, and their most basic orientation. So the rage and the frustration with a sense of betrayal by an authority figure was real, but kind of deliberately done in this mock comic mode: you know, like where Beckett railed against an absent God, this was me railing against these guidebook writers. It helped to both admit that kind of frustration and diffuse it.”

The Shikoku walk was particularly gruelling, lending the Camino chapter by contrast the air of an extended party.

“Oh, it was incomparably more difficult. There was never a moment on the Camino where I thought I might not make it. There were moments where I was in pain, but I loved everything about it. It was social, it was interesting, there were always people around. I’d gone to Japan hoping it would feel the same way, I really found that rich, spontaneous sense of community that one gets as a group of fellow sufferers to be a tonic, and I was hoping for that again, but then in Japan there was never anybody around, or if there were people they didn’t tend to speak English, there was nothing fun about it. Plus I was constantly on the side of roads with traffic, it was raining all the time. I mean, there were stretches of the Shikoku experience that were beautiful, especially when I was up in the mountains, it’s a beautiful place, and it’s not to say that there weren’t any moments of grace or equanimity, but it was not on the whole a pleasant experience.”

The Camino, however, is definitely a trip he’ll do again. Vicariously inspired by his experiences, I ask for tips for the best part of the trail to go on if you only had, say, a week to set aside.

“That’s a very good question. I thought the most beautiful walking was in La Rioja, in the area around Logroño, because it’s a vineyard area, and then the stuff in Galicia at the end is really beautiful. People say that it looks like Ireland, it’s so green, but the weather there is much less predictable, so I think I would start in Pamplona and go to Burgos, or maybe a little farther… I think the nicest bit to do would be Pamplona to Léon, I think that would be like ten days, and Léon is a really nice city and if you start in Pamplona you miss the gruelling days over the Pyrenees, or the one day over the Pyrenees and then the day or two down…”

With accommodation in the trail’s purpose-built albergue pilgrim hostels pretty basic, this stretch also has the added attraction of a greater concentration of boutique hotels in each of the cities passed through. (I later consult Google Maps to discover that this section covers the best part of 400 kilometres, which would demand a distinct improvement on personal bests, as well as a bicycle or several taxis, if I and my partner were to hit the ten-day mark.)

Noting that he geared the Tips for Writers he recently wrote for Bookanista to non-fiction only, I ask does Lewis-Kraus rule out ever trying his hand at fiction?

“I think so,” he says without pause. “I first wrote for and edited the humour magazine in college, mostly just because the people on the magazine were the smartest and the most interesting people that I knew. I’d never thought of humour writing before, and I found I wasn’t great at it but I wasn’t terrible at it, and then after a few years of doing that I thought actually maybe I want to write something else, I thought of it more as writing jokes than ‘writing’. So I decided I was going to take a creative writing class. I guess now they have non-fiction classes, but at that time they didn’t, so I had to take the fiction writing class, and I wrote these short stories that were totally derivative of David Foster Wallace. I would hate to look at them again. The professor said to me during the class, look, you have a nice way with sentences and description, but clearly your heart is not in writing fiction because you don’t care about any of the contrivances. And I said yeah that’s true, I don’t really care about fiction. I love reading novels, but in my writing – and I think this has to do with growing up with somebody who refused to be accountable in an adult way ever – one of the things that I really like about non-fiction is that feeling that you are somehow accountable to the world, that you’re accountable to publicly verifiable descriptions and facts, and I love when I write a piece and somebody says yes, that’s how it was, that’s how it is. Colm Tóibín had some line about how supremely accurate my section on the Camino is, from somebody who did it, and I get chuffed about that, when someone says that you nailed something. So to me that’s one of the pleasures of non-fiction; the hiding games that one plays in fiction are less interesting to me.”

Although, as we discussed at the start, there are hiding games in non-fiction too. In the book he talks about ‘transforming my actual misery into stylised self-deprecation… to lighten my burden’. So to what degree is the Gideon in the book stylised?

“Yes, this character is and is not me. Anytime you’re writing an ‘I’ you’re inventing a character for a specific set of focuses. I would still stand by this as myself, or as a particular version of myself.”

And does his dad acknowledge and accept his own depiction in the book too? Specifically the way he appears to measure his life against the characters in Will and Grace?

“Oh yeah, he doesn’t have a problem with any of that! I think it felt enormously comforting to my dad that a version of his life could be represented in a sitcom, a sitcom seeming like, you know, the epitome of normality.”

Our motives are always mixed. You know, everything is over-determined, and sometimes the only way one can get away with fulfilling a desire is by describing it as an obligation.”

In the last third of the book he comes back again and again to the idea that “what we often label obligations are really desires… there might, in the end, not be so great a difference between saying ‘I felt like it’ and saying ‘I had to.’” And he makes the point that this was also the case for medieval pilgrims – the pilgrimage could be as much about desire and escape as a religious duty.

“Our motives are always mixed. You know, everything is over-determined, and sometimes the only way one can get away with fulfilling a desire is by describing it as an obligation. It just has to do with, what are the bedrock reasons that your community will accept? So if you live in a community where it’s perfectly fine to say I’m going to take off and walk to Spain, then you don’t necessarily have to justify that. But in the medieval peasants’ world, the way that you justified leaving everything behind was to say you’re going on a religious pilgrimage. That was one of the only ways you could sell the idea to the people around you. Not ‘I want to’, but ‘I’m commanded to.’ But I also think everybody’s doing this constantly. I know a lot of people who use their work as the closest-to-hand excuse to justify what they do in the rest of their lives.”

It’s almost two years since the US edition came out, and although now based in New York Lewis-Kraus has since continued to flit east and west in search of stories.

“I’ve travelled to a lot of places in the last two years. I’ve been back to book criticism and narrative non-fiction magazine pieces. I’ve spent a lot of time in Japan, where my brother was living after he left Shanghai. I wrote a long piece about Japanese internet cats for Wired, I wrote a story about a co-sleeping café where one pays to sleep next to a professional sleeper for periods of time…”

I concede that he might need to go to Japan to research the sleeping café, but the internet cats?

“Well that’s a very long, involved story. Essentially I pitched this almost as a joke to an editor I’d worked with for a long time. I sent him a completely deadpan paragraph saying you should send me to Japan to profile Moru, the most famous cat on the internet – Moru has since been superseded I think, so at the time the most famous cat on the internet – and he called my bluff and brought it to an editorial meeting. In the end I couldn’t actually get access to that cat, but it’s a big thing putting your cat on the internet in Japan and it ended up being an essay about proxy self-expression. I also went back to Japan for a piece that hasn’t come out yet to go to a national hole-digging contest that my now sister-in-law was participating in through her company’s morale programme. Most of those were just excuses to go visit my brother – and because I really like Japan, I like writing and reading about Japan. What else have I done? I was in Georgia for a piece in September, I did a travel piece where I took trains from London to Istanbul doing a sort of DIY Orient Express that was fun, that will come out in the Times next month…”

So no book projects on the back burner?

“Possibly… I just spent all of January in San Francisco, again for Wired, writing a story about start-up failure. It was interesting to spend some time out there again and to write about youth culture in the context of Silicon Valley and who these people are starting companies and why. At the moment there’s a lot of moving pieces, but I’m trying to put together a Silicon Valley book. I’m pretty much done writing about myself. I think everything I do will have some first-person element, but I’ve said what I have to say about my life.”

A Sense of Direction is published by ONE, an imprint of Pushkin Press. Read more.

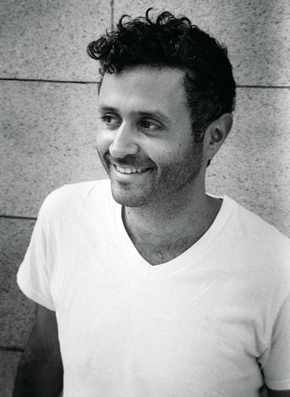

Gideon Lewis-Kraus was born in 1980 and grew up mostly in New Jersey. He attended Stanford University and lived in San Francisco, Berlin and Shanghai, before settling in Manhattan. He is a contributing editor at Harper’s magazine and has written for GQ, n+1, Wired, The New York Times, the London Review of Books and the TLS.

gideonlk.com

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.