Jean-Baptiste Andrea: The child within

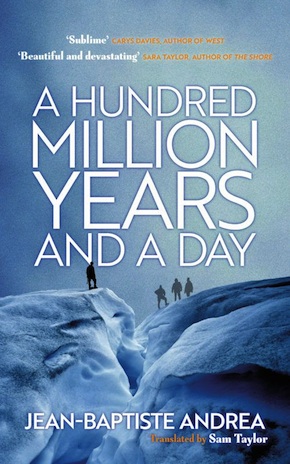

by Mark ReynoldsJean-Baptiste Andrea’s A Hundred Million Years and a Day is the fictitious story of fifty-something Stan, a middle-aged fossil-hunter who, in the summer of 1954, is driven to undertake a hazardous expedition to a mountain glacier to discover the whereabouts of a mythical ‘dragon’; a probable dinosaur skeleton embedded beneath the ice. He gathers together his loyal friend and former student Umberto, Umberto’s eccentric young assistant Peter and experienced local guide Gio for a life-defining trip that becomes a poignant journey into Stan’s past.

MR: To what extent do you share Stan’s obsession with dinosaur fossils and the lure of the mountains?

JBA: I love the mountains. It’s my favourite place in the world, and I grab any excuse to go there. Fossils were an earlier phase of my life. I wanted to be a palaeontologist when I was around 12, having been told that being a writer (my first choice) wasn’t a real job. I got into geology and all that, I was quite geeky. But that was a long time ago. A Hundred Million Years and a Day is not a book about palaeontology.

What has been your own most reckless or risky adventure?

I’m not trying to be clever here, but… becoming a writer. I received the French equivalent of an Oxbridge education, and I’m grateful for that, but I was bored to death (and to be fair, not very good at it). All I wanted to do was write, and that’s from an early age. So as soon as I graduated, I put my degrees in an envelope and started from scratch. And I got lucky – or was stubborn enough – to get my first break within five years, when I made my first movie. And then it was back to square one for another five years. It’s been a bit hairy sometimes, but I would redo it in a second.

That said, my fondest memory of a physical adventure is of a winter raid I did with close friends in the Alps. We spent a week in the snow, sleeping in a tent at minus 20 degrees, and that was a very unique thing. You somehow experience what life was before the invention of fire. But we were well equipped. I don’t take any unnecessary risks or put myself in harm’s way for the thrill of it. Too many people see the mountains in terms of conquest, competition, I’m completely against that. Humility is paramount in that kind of environment.

The planet we live on doesn’t belong to us. Mountains are not from one country or another. We seem to think we own nature, we do not, and very recent events have come to remind us of that.”

Stan sets out on an internationally-led expedition in the mountains that border France and Italy, which are a no-man’s land in every sense. Both France and Italy as we know them today are recent constructions in the scheme of history (and even more so for Stan and his contemporaries in the summer of 1954). Was it your intention to blur national borders as well as to reflect on humankind’s relatively short yet potentially disastrous span of time on the planet?

Absolutely! Thank you, not many people see that. I wanted to underline the absurdity of the concept of borders. The planet we live on doesn’t belong to us. Mountains are not from one country or another. We seem to think we own nature, we do not, and very recent events have come to remind us of that. Some people seem to think they’re different or superior or entitled to this or that simply because they come from one country or another – it’s the most ludicrous idea ever. The book is about a man who sheds everything that’s artificial about him – civilised as it were – in order to somehow become one with nature. Something we should all do, even if it doesn’t have to be in such an extreme fashion. There is very much a political and environmental message behind this story. About being together as a species, beyond borders/races/sexes, and developing a symbiotic relationship with the world we live in.

The hunt for the ‘dragon’ is on the hearsay of a child, and each of the four men who climb the mountain share a thirst for adventure that verges on madness. Are all explorers a little impetuous or crazy?

My story is fictitious. But if you look at great adventurers or explorers of the past, distant or not, most if not all of them were what could be considered mad, or crazy, or borderline suicidal. I say visionary. You see something nobody else sees, so of course they’re going to call you crazy. And you need to be, a little bit, to give up on comfort and normality for the unknown.

Stan’s time up the mountain has strong echoes of Touching the Void. Was that film a touchstone for you as your story developed?

I love Touching the Void. But I actually haven’t thought about it in years. Unconsciously, who knows? As a rule, I’m a fan of mountain movies, Touching the Void, The Dawn Wall, Free Solo, Meru, you name it, I’ve seen it. At the end of the day, all these movies, and A Hundred Million Years and a Day also, are about that crazy spark within us, that rebellious spirit which wants something big out of life.

You have said you’ve now given up filmmaking in favour of literature. How would you reply if you were asked to adapt and direct this novel for the cinema or TV?

Thank you very much but no. This story was always a novel. But if someone else wanted to adapt it, why not? I actually think it would make a great movie. But my job here is done.

Stan’s final challenge is solitude, isolation and almost certain death; which force him to take stock of his past. What can solitude teach us?

Probably a lot, considering pretty much every culture associates the figure of the hermit with wisdom. It’s quite obvious that if you cannot find happiness on your own, you will never get it from society. I would go as far as to say that society will not bring you happiness at all, and that the best you can do out there is not let others destroy who you really are. But then I have strong hermit-like tendencies myself, much to my family and friends’ despair (yes, I managed to make a few friends). Solitude is the first step towards happiness.

Your first novel, Ma reine, is told from the perspective of a damaged child, while Stan’s journey ultimately regresses into memories of childhood, his beloved mother and tyrannical father. Do you believe there is an age in early adolescence at which a person’s character and identity is more or less set for life?

“Set for life” might be a bit strong, in that one can and will always change. But yes, I do think that who you really are, you know very early on. And then, from your teenage years on, the world around you will somehow try to destroy that person, that real you, and turn you into a good little robot, so that you can fit nicely among the other robots. Sounds a bit harsh, and I’m exaggerating a bit, but barely. My adult life is spent preserving the child I was – am.

To what degree is our character set by following or rebelling against our parents?

Parenthood is everything. Those among us who were able to follow and rebel – both are needed – are the lucky ones. Because they had an example to follow and rebel against. Not everyone has that luxury. Some kids have no parents, or terrible parents, and what it does to them is unfair and heartbreaking. I admire the ones who managed to survive that.

I would go as far as to say that society will not bring you happiness at all, and that the best you can do out there is not let others destroy who you really are. But then I have strong hermit-like tendencies myself.”

What have you learned from touring with your novels and meeting readers?

That writers toured with their novels and met readers! In the film industry, this relationship is virtually non-existent. And because writing is such a lonely job, because you sometimes wonder if anybody else other than you is going to understand what you’re writing about, it’s fantastic when you realise you’re not alone. That people actually do get you.

How did you find working with Sam Taylor on the translation of A Hundred Million Years and a Day? Did the process open up any new insights?

It was great. Having written scripts in both English and French, I know first-hand that if I were to write the same scene in French and in English, both scenes would ultimately be a bit different and not a perfect match for each other. The differences would be mostly in the dialogue. So the first thing I told Sam was to not be afraid to betray the original text if needed. What mattered was to get the emotions, the tone right. I’m a great believer in the traduttore/traditore concept. The translator is and has to be a traitor. In the end, because Sam’s such a great translator, he managed to find a way to actually stick to the original without it feeling awkward. He had his job cut out: in terms of tenses, for example, I’m taking quite a lot of liberties in French which were not easy to deal with. Sam was also kind enough to let me have a look at his work, which both demands great humility and a fantastic amount of self-confidence. Having the writer peer over your shoulder could be unsettling. It didn’t faze him. I hope we’ll work together again soon.

Are there any plans for an English translation of Ma reine?

Not that I know of at this stage. Maybe later, who knows.

What themes connect your two novels to date?

The child inside of us, the spark, the spirit, whatever you call it, this thing which beats inside us and should never be allowed to die. Actually it never dies. But it can go to sleep, until we actually die.

What are you writing next?

The theme of my third novel is in one of the answers above. Won’t say more!

Where are you happiest, or most in awe?

Here. Now. Seriously. But if you really need a place, again, take me to the mountains…

Jean-Baptiste Andrea was born in 1971 in Saint-Germain-en-Laye and grew up in Cannes. Formerly a director and screenwriter, his first novel, Ma reine (2017) won twelve literary prizes, including the Prix du Premier Roman and the Prix Femina des Lycéens. A Hundred Million Years and a Day was shortlisted for the Grand Prix de l’Académie Française 2019 and the Prix Joseph Kessel 2020, and awarded the 2020 Prix des lecteurs lycéens de l’Éscale du livres. Translated by Sam Taylor, it is published in paperback and eBook by Gallic Books.

Jean-Baptiste Andrea was born in 1971 in Saint-Germain-en-Laye and grew up in Cannes. Formerly a director and screenwriter, his first novel, Ma reine (2017) won twelve literary prizes, including the Prix du Premier Roman and the Prix Femina des Lycéens. A Hundred Million Years and a Day was shortlisted for the Grand Prix de l’Académie Française 2019 and the Prix Joseph Kessel 2020, and awarded the 2020 Prix des lecteurs lycéens de l’Éscale du livres. Translated by Sam Taylor, it is published in paperback and eBook by Gallic Books.

Read more

@BelgraviaB

Author portrait © Vinciane Lebrun-Verguethen

Sam Taylor is an author and former correspondent for the Observer. His translations include Laurent Binet’s HHhH, Leïla Slimani’s Lullaby, Riad Sattouf’s The Arab of the Future and Maylis de Kerangal’s The Heart, for which he won the French-American Foundation Translation Prize.

samtaylorwriter

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.

@bookanista

wearebookanista