Jini Reddy: Believing is seeing

by Farhana GaniIt’s the book I didn’t know I needed. In vicariously joining Jini on her quest (albeit from the confines of my sofa), I found an honest and curious companion who opens her heart to us, sharing her background, fears, pain and desires and her mission to find a deeper sense of belonging. She’s completely true to herself and disarmingly funny.

Click on any image to enlarge and view in slideshow

For so many of us, the pandemic has opened our eyes to the great outdoors close to home. Social distancing and travel restrictions meant most of us were confined to limited time outdoors for a few months, and when we ventured outdoors it was for exercise or to go to nearby shops. There was less traffic on the roads and in the air. Pollution began to subside and wildlife thrived. Birdsong became audible, goats brazen, deer uninhibited and we all began to take time to smell the roses. Life slowed down. There were no sports on TV. And the weather was good. Suddenly we were watching bees buzz around lavender, feeding foxes and getting to know the trees. Instagram and Facebook pages filled with photos of flora and fauna taken on neighbourhood walks. There was excitement. Could this new-found love of nature ultimately heal the planet?

Like Jini, I’m Indian born to South African parents and I grew up on three continents. And I empathise with Jini’s tales of being made to feel Other, just as any non-native in Britain will have experienced now and then. I’m a roamer, and holidays mean hiking. Like Jini, my health veered in a direction of its own and knocked me sideways, and like her a deep grief for my cherished father has changed the essence of me. How do you bear each day when the person whose ideas and opinions on our changing world were always the first you sought is no longer amongst the living?

This seemed to be where our similarities end. I’m a nature lover, not a tree hugger. But my curiosity was stirred, and Jini’s raw honesty meant that if anyone was going to convince me there’s magic in the landscape, it would be her. Sure enough, the day I finished reading Wanderland, I was pottering in the back garden. A particular sycamore (a non-native, naturalised species) loomed large as usual. It was the favourite scratching post and climbing challenge of a long-time cat companion of mine. And for the first time ever, I hugged a tree and stroked its bark. It felt right that I finally said thank you to it for giving Jack such pleasure for 18 years.

Jini’s quest is as thrilling as it is fascinating. The book opens with a spooky and ethereal experience while camping alone in the Pyrenees, causing her to wonder what is truly out there, and closes with a trip to Lindisfarne that began with good intentions but challenged a close friendship. In between, across Britain, there are labyrinths to unravel, trees to whisper to, wild art to contemplate and mythology and folklore to learn about, spliced together with stories of growing up in a world in which she will always stand apart.

I was seeking to connect with an animate nature, the spiritual dimension of landscape, the Divine even – I saw it as a journey, and I was wanting to follow my curiosity.”

Throughout, she doesn’t hold back from sharing all aspects of her travels, emotional and physical. And that’s what makes Wanderland such a powerful narrative. Jini’s Pyrenees encounter leads her to seek something similar on home turf, and in Iona, quite out of the blue and palpably thrilling, the most wondrous series of coincidences connecting mind, time and nature reveal the elusive path she’d been searching for fruitlessly in the days before.

Her gentle, determined personality shines through her writing and her curious nature means she asks questions of everything, which is deeply satisfying. She is a natural and instinctive storyteller and you feel you’re with a kindred spirit as she generously shares the marvellous alongside frustrations and personal intimacies. Her writing has undoubtedly woken something in me, and with holidaying at home being the right thing to do this year, I’m now the happy owner of a list of destinations to reawaken my metropolis-numbed senses.

I caught up with Jini to delve deeper into her search for magic in the landscape and to discuss the wider world around us.

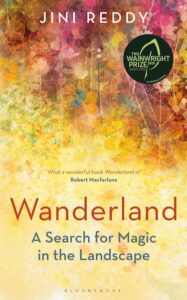

FG: Congratulations on being shortlisted for the Wainwright Prize. What does this mean to you?

JR: I’m feeling a joyous glow about it all! It gives me much greater confidence as a writer – also the recognition that a book like mine, which straddles a few genres can be acknowledged and appreciated in this way, is heartening.

You write about ‘craving an intimacy with the land’. What do you mean?

I was seeking to connect with an animate nature, the spiritual dimension of landscape, the Divine even. I’d been a travel writer, and I’d had opportunities to meet people from indigenous cultures, I was always inspired by the way that for those I’d met it was perfectly natural to experience this kind of deep reciprocal relationship with the forces of nature. I wanted to know if a regular person like myself might be able to experience a glimpse of the world in this way – I saw it as a journey, and I was wanting to follow my curiosity.

And how did select which areas to visit – or did they choose you?

I didn’t organise my trip in the conventional way – I didn’t resort to a map and compass, rather I was trying to enter into the spirit of my endeavour. In a very playful, experimental, trusting way, I chose to seek counsel from the land to guide me: I was willing to enter into that intuitive, non-rational space, and see where it led me. I followed signs, clues, and whatever information presented itself to me. I really do believe that creativity is as much about a listening and a receiving as it is a doing.

Most of your travels were solo. Was this a conscious decision?

Yes. I find that when I travel alone, my experience is a more… full-bodied, immersive one. It’s easier to pay attention to what is around you, and to what is within you when you are alone. I travelled with a friend recently and it was great fun, but now that I’m back my memories of the place we were in are not as sharp or defined as they would be if I’d travelled alone.

The shock and pain of losing your father and sister two years apart is tough to bear. And then your GP sounded a warning bell about your own health. How much did these events influence your mission?

I wouldn’t say they greatly influenced my mission in a conscious way, but these experiences and that loss are a part of me, and that fear of death is always there. Any opportunity for healing of any kind I’ll take. I suppose there is a part of me that wants very much to believe there is a life beyond this one. I crave that reassurance.

In times of sorrow or when we’re feeling adrift, why do so many of us reach out to the wilderness?

On one level nature has the power to soothe – green is a calming colour, there are (often) wonderful scents to inhale, clean air, beautiful scenery, no man-made sounds to jar, there’s an escape from the incessant information overload of the modern world, the kind of stimuli that are hard on the nervous system. On another, deeper level, I think we unconsciously respond to the call of the wild because we humans are a part of the wild. We’re the human aspect of the natural world. So instinctively perhaps we gravitate to this bigger part of ourselves that we are embedded in.

It’s not that unusual to have experiences that go beyond the ordinary. There is a lot that goes on beyond the rational – it’s all about broadening our field of perception, something we in the West are not good at.”

Your experience in the Pyrenees feels supernatural. Do you know of anyone having a similar experience? Can it be explained ‘rationally’? It was also deeply intimate. Did you hesitate at all about sharing those details with us (and your mum!)?

Oh yes, it’s not that unusual to have experiences that go beyond the ordinary. As for me, I don’t feel the need to explain it rationally. There is a lot that goes on beyond the rational – it’s all about broadening our field of perception, something we in the West are not good at. That said, no I couldn’t explain it rationally. I went through all the possibilities and none made sense in that context. And it was a one-off thing! It wasn’t like I have supernatural experiences every day! My mother is totally cool with all of this – there are in healers in my family. My grandfather on her side (who died before I was born) used to perform exorcisms. My mum has often spoken of an aunt who was a legendary healer. And my late father was a child psychologist but he would have been open to the mystery of it, too, I’m sure. As for sharing it in the book, oh yes, I hesitated big time – but then I felt that way about the entire book!

The search for the spiritual, a desire to connect with nature at a deeper level is thought of as ‘woo woo’, hippie, eccentric even. How do you deal with such scepticism, and what will it take to alter perceptions?

I’m not trying to persuade anyone to leave behind their scepticism. How people receive the book is up to them, I just put it out there! But I have been heartened by the reaction to the book by the sort of people who I’d imagined would out-and-out dismiss it – people from mainstream nature and conservation circles, and book reviewers in the mainstream press. It’s had wonderful reviews in, for example, the TLS, the FT, the Observer and even, yes, the Mail on Sunday! But equally magazines like BBC Wildlife have been really positive about it. I did a thing for Springwatch’s lockdown digital show, and dear Chris Packham – the least spiritually inclined person I can think of – was supportive! And I love that media directed at people who are black or Asian or from other marginalised backgrounds have picked up on it – like Eastern Eye and Brown Girl Magazine. That such a broad range of people have connected with a book I’ve written on a quite esoteric theme has really amazed me and been the best thing about all of this.

As well as a search for the magical and the divine in the land, Wanderland is also a story about belonging. You write about strangers’ eyes lingering on you long enough to make you feel like an outsider, causing you to be wary of walking into rural pubs on your own. Can you explain more about how you felt about this at the start and end of your year-long journey?

I mentioned all of that because it is part of my reality, but I’ve always felt that way, and probably always will to some degree – there’s no getting away from it. But equally I’ve travelled widely in the world, and fairly widely in Britain even before writing this book, and I am accustomed to feeling hypervisible, at times.

But I am fundamentally a person with a positive outlook. In terms of the journey, as a result of doing it I feel more centred in myself, more quietly confident than I did. A lot of that has to do with publication of the book, and with feeling, finally like a ‘proper’ author. I’ve wanted to be a writer from the time I was a small child. I adore fiction, I adore creative non-fiction. I’m not coming to any of this as a naturalist or a specialist…

That part of me that is deeply interested in the spiritual was allowed to surface in writing the book, and so coming ‘out’ in that way has been empowering too.

In Iona, remarkably, everything fell into place in quite a magical fashion. Did you have an epiphany?

Iona was amazing – it genuinely did happen like that! It was a perfect illustration of what I mean about connecting with the spiritual dimension of the landscape. You can’t imagine how deeply joyful and awe-inspiring that felt. It opened doors in my heart and expanded my field of perception – I know without a doubt that there is more going on than meets the eye, and this informs how I journey in a physical sense as well as how I live my life more generally. I love it, I feel like a spell-caster at times. (I’m also human and have really bad days!!)

You talk about wanting to hear nature’s voice. And to listen more to nature. Can you explain this?

I think I probably touched on this earlier: I was seeking to connect with the Divine in the landscape, the spiritual dimension of nature – that’s what I mean by nature’s voice. Like many I celebrate the physical beauty of wild landscapes and the natural world, but I equally want to connect with an animate nature.

You’ve travelled extensively, and there’s something of the nomad about you. Where is home for you?

Oh, I love this question because it is very ‘live’ for me right now. It’s something I grapple with. I live in southwest London (and was born here) so in a sense that is home but I grew up in Canada, my parents are Indian and from South Africa, so I feel half my heart is in Canada, and bits of me connect with bits of Indian and South African culture.

I have the fondest memories of the Saint Lawrence River, or at least the stretch that flowed past the end of my street and led to rushing rapids. That place, for me, is heaven.”

Children, it is said, are more in tune with natural world before structured conventional education kicks in. Your early life in Canada sounds idyllic. What are your most treasured memories of childhood there?

Oh, I have so many gorgeous memories. When we first moved to Canada we lived on the edge of a tiny village in the Laurentian mountains. The back garden was a wilderness, and we arrived in a blizzard, and it was like entering a winter wonderland. (I’ve written about this in the book.) I remember putting on snowshoes for the first time, going sledging, and exploring the slopes in summer, picking blueberries in the fields with a chum. We moved to Montreal a couple of years later, and I have the fondest memories of the Saint Lawrence River, or at least the stretch that flowed past the end of my street and led to rushing rapids. That place, for me, is heaven.

You write honestly about your embarrassment as a child about wanting to belong, and you adopted an English-sounding abbreviation of your name. How others relate to your ethnicity (or how you are made to feel about your ethnicity) runs throughout the book. Do you still feel the need to ‘belong’?

So first of all, I definitely didn’t adopt an English sounding abbreviation of my name. I want to clear that up! My parents named me Sarojini at birth, and that is what it says on the birth certificate, but from the time I was born both called me Jini. So I totally and utterly identify as Jini. They’ve never called me anything else! I’m not dismissing my background, or trying to be more acceptably white or ‘English’. Jini is just who I feel myself to be. If they’d called me Sarojini growing up it’d be different. An author recently had a go at me for not using my full name – and I thought, you’ve not got a clue, people are nuanced individuals, with individual stories.

I think I have a much greater sense of contentment right now – so that’s what belonging feels like for me. I also have more of a voice now, and having a voice gives me a feeling of belonging.

The Black Lives Matter movement has gained momentum this year. The UK leadership is determined to paint the nation as generous, ‘tolerant’ and ‘least racist in the world’. Having lived in different countries and experienced diverse cultures, what is your opinion?

My experiences abroad have generally been really positive, as they have been here. On the whole I do believe this is a tolerant nation – that said, whether you experience the UK as a tolerant place or not depends on where you are geographically and in terms of your circumstances too, I think.

Structural racism, and everyday racism in the stories of hurt and pain people share, the awful demonising of refugees and asylum seekers are all a terrible blight on the UK. Our so-called leadership often feels like a compassion-free zone, blinkered and wilfully obtuse. I believe little will really change until there is a willingness to look colonialism and Empire in the face, that system of domination and control, and consider how it has viewed people who are black or Asian as inferior or backwards. The trauma of that has to be valued. There has to be recognition that this system has created the structural racism that is in place and persists today. The cultural attitudes embedded in our social fabric for generations as a result of colonialism need to be brought into the light of day, confronted and taught in schools.

Many in the media who once embraced the BAME acronym are now publicly distancing themselves from it, seeing it as a weapon to perpetuate the Other. What is your position?

I loathe the acronym. I always have. I find it hideously reductive. I’m a human being not a monolith. We’re talking about people from vastly different socio-economic backgrounds, and ancestral heritages and cultures, people whose philosophies and politics and experiences of life vary wildly.

Lockdown has offered many the opportunity to slow down and reflect. What has your lockdown experience been like?

Apart from the fear factor, on the whole OK. I live in a green southwest London suburb and have a wood at the end of my street. I have a bicycle and used the time to explore nature reserves and parks I hadn’t ventured to before, because the usual places I’d gravitate to were off-limits or too crowded. I really enjoyed that feeling of an amplified connection with the natural world and the slowing down. In fact, I’ve resolved to stay in the slow lane! But I also launched my book in lockdown and that was pretty intense, suddenly having to get up to speed with digital festivals and zooms and podcasts. I’m quite shy and all of that has been a steep learning curve and hard on the nervous system.

It’s lovely to read a book whilst resting against a tree! Plus, they release oxygen and absorb carbon dioxide, and are a home for wildlife. We all ought to be tree worshippers.”

Trees loom large throughout the book. You clearly have a passion for trees and you hug them – but only when no one is looking! Do you have trees as friends?

Ha ha! I do love trees, but not in an overly geekish way. I just think they’re quite beautiful. It’s lovely to read a book whilst resting against a tree! Plus, they release oxygen and absorb carbon dioxide, and are a home for wildlife. We all ought to be tree worshippers. I have a few local favourite trees – there’s a fig tree I’m fond of because of the scent coming off the leaves. Sometimes it’s there, sometimes it isn’t. I can never tell. And I love oak trees. And yew trees – I love the texture and colour of the bark.

The yews in Chalice Well Gardens in Glastonbury are said to transport people to other realms. Can you expand on this? Has anyone who has been on such a journey shared their experience with you?

At Chalice Gardens, I met a ‘priestess of the Goddess’ – a woman who honours the feminine aspect of the divine. And she mentioned that story about the yews briefly, in passing. But again we are alighting on experiences and perspectives that exist beyond the rational, and start with a belief in an animate nature. I’ve never been on a journey with yew trees, no, but I know of people who have. (I did have an interesting experience with dandelions once though – in my first book, Wild Times.) There’s a brilliant book called 52 Flowers That Shook My World by Charlotte Du Cann which I read a few years back. I definitely recommend it. And, on the trees front, a book called Plant Spirit Medicine by Eliot Cowan. He can definitely talk trees! I adored Richard Powers’ Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Overstory, by the way. It’s all about the wisdom of trees.

Do you trust our policymakers when it comes to protecting and nurturing our natural world? What would you like to see happen from government in the UK and internationally?

Given the hunger for expansion and growth on a planet with finite resources I’d say no, I don’t trust them. On a global level there needs to be an understanding that environmental justice is also about social justice – people and planet are interconnected. You can’t care about one or the other in isolation. You also have to ask yourself who the traditional models of conservation are benefitting. Historically, for example, the creation of the US National Parks, with Yellowstone in 1872, involved ethnic cleansing – Native Americans were forcibly removed. Wildlife tourism in African countries today tangibly contributes to conservation but there’s little diversity in terms of clientele, and who owns and operates these outfits? How much of a stake do local park rangers and porters and hotel workers have in the decision-making process? The issues are complex. In the UK, there is a lot of talk right now about access to natural landscapes – some people can’t even afford the gear to go walking, so how are they supposed to care about nature? And why is it not obligatory for all new housing developments to be built with eco-friendly materials, and with green spaces?

Michelle Obama has talked about suffering from a ‘low-level depression’ brought on by the state of the world. Factors such as the health of the planet, weak leadership, tribalism, all feed into this malaise. Here in the UK, it feels like helplessness has crept in, for instance protest about climate change has subsided. How can the nation be shaken out of this apathy?

I had an interesting conversation just yesterday with someone about this – on the one hand she believes in the value of expressing gratitude for every good thing in her life, but on the other isn’t sure what to do with the anger and helplessness she feels feel at all the injustices in the world. I think we’re at an interesting point in history. I think we’ve lanced a boil and a whole lot of gunk is coming out. It’s going to be a tough going for I don’t know how many years. My feeling is that the planet will ultimately be OK, and will regenerate – decay is a part of the cycle of life, after all – but we, as humans, may not be OK. In the here and now, I think we also have a responsibility to ourselves, to our loved ones and to the planet, to allow ourselves to feel moments of joy. Despite the difficult times we live in, wonder and magic still live on. Love is a powerful force.

If more of us can be persuaded to listen to the landscape and hear nature’s voice ourselves, could this be where hope may lie?

When we experience feelings of kinship with the natural world – in other words, rather than separating ourselves from nature and merely being observers, actually recognising that we are the human part of nature, that those beautiful landscapes are an extension of ourselves – love grows. We care and want to protect what we love. And why would we want to hurt a part of ourselves? We can draw wisdom from people from indigenous cultures around the world, for whom living in harmony with the natural world is a given. I’d recommend taking a look at the work of Flourishing Diversity and The Gaia Foundation as a starting point, in a nice accessible way. hold many of the answers to our most pressing problems concerning the climate crisis

Who are your role models?

I have a lot of respect for care-givers, i.e. nurses, doctors, paramedics – I’ve experienced first-hand the kindness and compassion of NHS hospital workers. I admire anyone who works tirelessly to ease the plight of refugees and asylum seekers. Generally, I have the greatest admiration for people who combine wisdom with humility. People who listen well.

Where are you travelling to next, and will it involve magic?

I’m just back from the Isle of Lewis – I hadn’t expected to go there. But every B&B and cottage in Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly (where I’d wanted to go originally) was booked, so I took a leaf out of Wanderland and sought counsel from the land.

I knew the drill: quieten down, humbly ask for guidance, look out for signs, trust… And that led me (and a friend) to the Western Isles. We ended up there in the hottest week of the year – and this is Scotland! We were dazzled with sunshine, had white-sand Caribbean beaches and staggeringly beautiful coastal paths to ourselves. The islanders were friendly and kind and helpful. We encountered spirited sheep and beautiful shaggy Highland Cattle, and astonishing sunsets. If that’s not magic, I don’t know what is. Everything was with us and we started and ended everyday with ‘thank yous’. Thank you land, thank you sea, thank you sand, thank you sky, thank you, thank you, thank you.

Thank you Farhana, for this lovely interview

Jini Reddy was born in London to Indian parents from South Africa, and was raised in Montreal, Canada. She has a degree in Geography, an MA in English Literature and a passion for writing on travel, nature and spirituality. Her first book, Wild Times, was published in 2016 by Brandt, and she is a contributor to the forthcoming Women on Natureanthology (Unbound, 2021). Wanderland is published in hardback and eBook by Bloomsbury.

Read more

jinireddy.co.uk

@Jini_Reddy

jinnyreddy20

Farhana Gani is a freelance writer and a founding editor of Bookanista.

@farhanagani11

@bookanista

wearebookanista