Judith Shakespeare

by Ramie Targoff

In her 1929 feminist manifesto, A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf explored the reasons why over the centuries women had written so little compared to men. “A woman must have money and a room of her own,” she famously pronounced, “if she is to write fiction.” In lectures originally given in 1928 at Newnham and Girton Colleges (both women’s colleges at Cambridge University), Woolf described her own circumstances – she had already written Mrs. Dalloway and To the Lighthouse – as a direct result of having inherited £500 a year from an aunt who died after falling off her horse in Bombay. Woolf got the news of her aunt’s gift around the same time that women were given the vote, in early 1918. “Of the two – the vote and the money,” she declared, “the money, I own, seemed infinitely the more important.”

What most readers remember from Woolf’s polemical work is her account of Shakespeare’s imaginary sister, Judith. If there had been a Judith Shakespeare endowed with a talent like her brother’s, Woolf warned, she would have met with the darkest of fates. “Any woman,” she exclaimed, “born with a great gift in the sixteenth century would certainly have gone crazed, shot herself, or ended her days in some lonely cottage outside the village, half witch, half wizard, feared and mocked at.” For in spite of her genius, Judith Shakespeare “would have been so thwarted and hindered by other people, so tortured and pulled asunder by her own contrary instincts, that she must have lost her health and sanity.” Had any woman survived these conditions, Woolf concluded that “whatever she had written would have been twisted and deformed, issuing from a strained and morbid imagination.”

Woolf had good reasons for her pessimism. To be a woman in Shakespeare’s England was to live a drastically reduced life. Girls were rarely permitted to go to grammar schools and were never allowed to attend university. Before marriage, they were supposed to serve and obey their fathers. Once married, women’s obedience shifted to their husbands, who assumed possession of their wives’ personal property and became their legal guardians. Renaissance women could not hold political office or vote. They could not become lawyers or doctors. They could not appear onstage in theatres. They were supposed to keep quiet in public, and disruptive behaviour could lead them to be brandished as ‘scolds’ and paraded through the streets wearing a heavy iron muzzle known as a ‘scold’s bridle’. Despite all of these restrictions and hardships, however, some women did learn their letters, read voraciously, and then take up the pen themselves. They weren’t encouraged, and they rarely found even a shred of acclaim, but there were some women who managed to write.

When Woolf wrote A Room of One’s Own, she knew almost nothing about the powerful literary works a small group of women had written – and in many cases, published – around the time of Shakespeare. These brilliant poems and plays, translations and histories, had been lost or forgotten for centuries. But Woolf had recently encountered one of these women’s writing, which she peremptorily dismissed as trivial. In 1923, Woolf’s lover Vita Sackville-West published the early diaries of Lady Anne Clifford, who had lived at Sackville-West’s childhood home at Knole. Sackville-West saw in Anne a kindred spirit, a fellow reader and writer who was dissatisfied with the prescriptive role English society had carved out for her, and who had heroically found a way to fight back.

That Woolf couldn’t grasp what was thrilling about Anne’s diaries reflects her own tastes and biases – but also gives us a different perspective on the reasons she thought Judith Shakespeare couldn’t have practised her art.”

Anne would no doubt have been thrilled to know that a woman like Vita Sackville-West brought her writing back into the world. She would have been less pleased with Virginia Woolf’s response. In her 1931 essay ‘Donne After Three Centuries’, Woolf described Anne as “practical and little educated,” someone who painstakingly restored her castles but “never attempted to set up a salon or to found a library.” She may have “read good English books as naturally as she ate good beef and mutton,” but in Woolf’s estimation, Anne’s writing didn’t deserve our attention.

That Woolf couldn’t grasp what was thrilling about Anne’s diaries reflects her own tastes and biases – but it also gives us a different perspective on the reasons she thought Judith Shakespeare couldn’t have practised her art. For it turns out Woolf’s doomed vision of women writers in Renaissance England was horribly mistaken. Although she claimed to have heard of “Lady Pembroke” (whom she might more respectfully have called by her own name, Mary Sidney), she seems never to have read a word of either Mary’s dazzling verse translation of the Psalms or her beautiful poems to Queen Elizabeth. She almost certainly hadn’t heard of Aemilia Lanyer, the first Englishwoman to publish a book of original poetry in the seventeenth century, whose brilliant poem ‘Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum’ offers a feminist retelling of both Eve’s fall and the Crucifixion. Woolf likewise knew nothing about Elizabeth Cary, whose stunning tragedy recounting the murder of the ancient Jewish princess Mariam at the hands of her tyrannical husband Herod, was the first original play to be published by a woman in England. Revisiting many of the themes of Shakespeare’s Othello written just a few years before, The Tragedy of Mariam bravely affirms a woman’s right to follow her own conscience and speak her mind at whatever cost.

Once we learn about these women and read their books after centuries of neglect, it’s not only their names that we recover. Suddenly, there are new voices. We hear from teenage girls married off to men they would never have chosen; wives forced to tolerate their husbands’ spending their money and taking lovers; mothers whose babies died before their first birthday, or whose children were taken away by their fathers as punishment for wifely disobedience. We hear from widows filing their own lawsuits in Chancery Court, opening charities and schools, travelling for pleasure to Europe, building their own houses, and erecting monuments. We hear a woman’s perspective on the killing of Mary, Queen of Scots and the Spanish Armada; the Protestant wars in the Netherlands and the witchcraft trials in England and Scotland; the ongoing persecution of Catholics and the outbreak of the Civil War. We realize that however much we thought we knew about the Renaissance, it was only half the story. We begin to understand how much we’ve been missing.

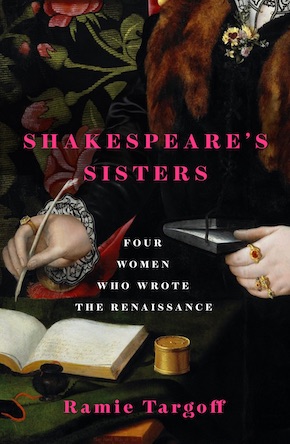

Abridged from the introduction to Shakespeare’s Sisters: Four Women Who Wrote the Renaissance (riverrun, £25)

—

Ramie Targoff is the Jehuda Reinharz Professor of the Humanities and Co-Chair of Italian Studies at Brandeis University. She holds a BA from Yale University and PhD from University of California, Berkeley. She is the author of several award-winning books on Renaissance English poetry, as well as a biography and translation of the sixteenth-century Italian poet Vittoria Colonna. She lives with her family in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Shakespeare’s Sisters is published by riverrun in hardback, eBook and audio download.

Read more

ramietargoff.com

@riverrunbooks

Author portrait by Frédéric Brenner