‘La lengua’: interpreters the colonial age

by Sophie Harbach

“Impeccably researched and engagingly presented, this fascinating book shows how languages arise, grow, borrow, mix and blend.” David Bellos

In August 1492, Christopher Columbus set sail from Spain, hoping to find a westwards trading route to Asia. With him were two interpreters, fluent in various European and Middle Eastern languages. Columbus himself, who was originally from Genoa in Italy, also spoke several European languages. Even within Spain, a multitude of languages coexisted, many of them still in use, such as Castilian (Castellano, now treated as standard Spanish), Catalan and Basque, as well as a number of smaller regional languages.

On this particular voyage, those language skills turned out to be useless. Hundreds of languages were spoken on and around the continent that Columbus eventually reached, and not one of them was related to the Indo-European family.

All invaders face a basic linguistic challenge. To capture a new territory, they may only need weapons and ruthlessness. But to capture the inhabitants’ accumulated cultural intelligence, they need to understand their language.

From the moment Columbus and his crew first sighted land, at Guanahani in the Bahamas, finding a way into that native wisdom was one of their central missions. They were aware that the people they met did not just have precious raw materials. They also had knowledge. They knew which other communities lived in the area, their habits, and the languages they spoke. They knew safe travelling routes, and the sources of fresh water along the way, and how to process raw ingredients into palatable food.

Gathering, editing and translating this expertise became a central goal for the Spanish, long after Columbus had died and others followed in his wake.

As early as 1503, the Spanish royal court encouraged the Spanish invaders to marry indigenous women, ‘so that they may communicate with and teach one another’. Later, the children of mixed couples used their bilingualism as writers and translators. Spanish-Quechua bilinguals wrote histories of the conquest of the Inca empire in Peru, and translated a range of European literature into Quechua. Their Mexican equivalents did the same with Nahuatl.

How did the very first Spanish explorers bridge the language gap? How did they do this for languages that had never been in contact before, and were not even linked by a third language?”

Eventually, this effort became enormously complex and sophisticated, involving teams of translators versed in several scripts and languages, scribes, editors, and of course, printers, who distributed the resulting texts in Europe.

One particularly influential figure in that process was Bernardino de Sahagún, a Franciscan friar from Spain who learned Nahuatl, one of the main languages of central Mexico. In the late sixteenth century, Sahagún set about collecting proverbs, stories and general musings from Nahua elders. He sent out teams of researchers, who asked the elders to write down their contribution in Nahuatl scripts. Bilingual students then transcribed this into the alphabet. From there, Sahagún translated it all into Spanish.

The result was a sprawling compilation known in English as General History of the Things of New Spain. It includes a loose collection of proverbs and metaphors that may have been intended as teaching materials for missionaries learning Nahuatl, based on direct quotes from the elders. Thelma Sullivan, a Nahuatl expert, describes these informal jottings as ‘word pictures’ that illustrate the life of the Nahuas, as well as their thoughts and feelings.

The work of these later generations of translators and interpreters built on the dictionaries and bilingual texts compiled by earlier ones. But how did the very first Spanish explorers bridge the language gap? How did they do this for languages that had never been in contact before, and were not even linked by a third language?

Linguistic hostages

Landing of Columbus at Guanahani, 14 October 1492 by John Vanderlyn, 1847. Architect of the Capitol/Wikimedia Commons

One quick and brutal strategy was to kidnap people and force them to act as guides and interpreters.

A couple of months after they left Spain, Columbus’s crew spotted Guanahani, an island in the Bahamas, inhabited by the Lucayans, or Lucayos in Spanish. A group of unarmed Lucayans appeared on the beach. Columbus went ashore with some of his men, planted a flag in the ground, and declared that they’d taken possession of the island. He noticed that these friendly, unarmed people had a gift for languages: ‘I have observed that they soon repeat anything that is said to them… I will bring half a dozen of them back to their Majesties, so that they can learn to speak.’ To speak, in this context, obviously meant to speak Spanish. Their own language was Taino, of which different variants were spoken throughout the Caribbean.

Columbus had seven Lucayan men ‘brought aboard so that they may learn our language’. The men initially communicated through signs. They also told the Spanish the names of the places around them, including more than a hundred island names.

As Columbus sailed from island to island, he met more indigenous inhabitants, exchanged gifts with them, and noticed that they wore gold bracelets. He asked them where the gold was and showed them some pieces of gold he’d brought along, to make sure they understood the question. The Lucayans continued to explain the area to him through signs, and guided him towards fresh-water sources.

The ships reached Cuba and Haiti, inhabited by more Taino speakers. En route, the Spanish abducted a group of a dozen men, women and children. As they were about to sail away, they were followed by a man whose kidnapped wife and children were on board. He begged to be taken along rather than lose his family, and they promptly took him, too.

From now on, the new encounters featured interpreters: the imprisoned people on board the ships, who quickly picked up some Spanish. As more people appeared on more islands, speaking ‘in the proud language common to all the peoples in these regions’, they communicated by signs, and also through a few words translated by the kidnapped interpreters. Already, the beginnings of a sophisticated dialogue were starting to emerge, with meaningful gestures, illustrative objects such as lumps of gold, a few words and place names, and some early, basic translations.

Some of the crew stayed on Haiti; the rest returned to Spain, along with a group of captive island interpreters. They were displayed to Isabella and Ferdinand of Spain, along with chilli peppers and sweet potatoes. More voyages followed, with larger fleets, landing on Guadeloupe, Antigua and, eventually, Venezuela, Honduras and Panama. European settlements, or colonies, were established in the wake of the explorers.

The only way to study their culture and belief system is through the artefacts they left, [but] Taino loanwords continue to be used in many modern languages, including the words barbecue, hurricane, canoe…”

For the Taino, the Spanish arrival was disastrous. Almost all of them were eventually killed by European diseases such as smallpox and even the common cold, to which they had no immunity. By about 1600, only a century after Columbus spotted their land, the Taino community had been mostly wiped out. The Taino did not write their language down. The only way to study their culture and belief system is through the artefacts they left, such as human-shaped ceremonial stools, called duho. Taino loanwords also continue to be used in many modern languages, including the words barbecue, hurricane, canoe, hammock and tobacco.

A second strategy was to train a Spanish crew member in a local language. Cristóbal Rodríguez, a sailor who accompanied Columbus on his later trips, was the first European to learn a language from the Americas. He acquired Taino on Haiti, by living with native speakers. According to Bartolomé de Las Casas, a sixteenth-century Spanish colonist and historian, Rodríguez was ‘nicknamed “la lengua” (“the tongue”) because he was the first to know the language of the Indians from this island, and he was a sailor who had spent several years working among the Indians, without talking to any Christians, to learn it’.

Later, conquerors such as Hernán Cortés found shipwrecked Spanish sailors who had been captured by indigenous communities and mastered their languages while living among them.

Doña Marina, chief interpreter

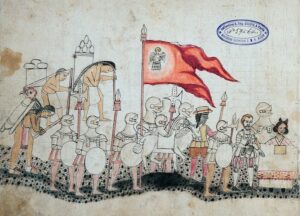

Hernán Cortés and Malinche (far right) at the court of Azcatitlan in an early 16th-century indigenous pictorial manuscript of the Conquest of Mexico. Gallica Digital Library/Wikimedia Commons

Since many different languages were spoken in and around the Americas, the kidnapping strategy was repeated over and over by Columbus and his successors, such as Hernán Cortés. People were either just bundled onto the ships or handed over by chieftains as part of peace deals.

In one of these peace deals, a chieftain on the coast of Mexico gave twenty women to Cortés and his men. One of them was baptized Marina by the Spanish. Pronounced with her native accent, this became ‘Malina’. Later, after her fortunes had changed dramatically, her people turned this into an honorific form: ‘Malintzin’. In one of the linguistic boomerang effects that are so common in human history, ‘Malintzin’ was then heard by Spanish-speakers as ‘Malinche’.

Malinche, as she is known to this day, is possibly the most famous interpreter of the conquest era. She helped the Spanish prise open the many, many indigenous languages of Mexico. Her voice mediated between the two most powerful men in her world: Hernán Cortés, who had come to conquer her land, and Moctezuma, the god-like ruler of the feared and mighty Mexica.

Cortés called her ‘la lengua’, the tongue, the interpreter. And she did have a magical tongue, one that could produce four or five languages. Not just that, but she understood how these languages related to each other, how they could be translated, which additional interpreters were needed to fill the gaps, and how they could be recruited in slightly more diplomatic and skilful ways than kidnapping. She rose to become what the Sumerians would have called ugula eme-bala, a chief interpreter.

In the 1960s and 70s, some Mexican American feminists adopted Malinche as an icon. Loved or loathed, she’s been recognized as a crucial figure in the conquest, inspiring countless books, essays and films.”

In Mexican Spanish, Malinche’s name is synonymous with selling out, betraying your people and heritage, cosying up to powerful foreigners. However, she’s also been defended as someone who just did her best with what she had. After all, many indigenous people translated for the Spanish. In the conquest of Peru, an indigenous man known as Felipillo learned Spanish from the conquerors, and interpreted between them and Atahuallpa, the Inca ruler. Without such mediators, the two sides would have struggled to communicate at all. As one Inca leader told the Spanish: ‘it is quite impossible for me to understand your weird language’. (Felipillo’s status in Peruvian culture is also conflicted, with some accusing him of treason, and others arguing that he ultimately sided with his people.)

In the 1960s and 70s, some Mexican American feminists adopted Malinche as an icon. They dedicated bilingual poems to her, defiantly declaring ‘Yo soy la Malinche’, I am Malinche. Loved or loathed, she’s been recognized as a crucial figure in the conquest, inspiring countless books, essays and films. And yet the skill that catapulted her into her unlikely role is often strangely ignored: her multilingualism. Her ability to interpret between languages, which is a second skill in itself, has also often been taken for granted.

A closer look raises many questions. What do we know about the languages Malinche spoke, and how she learned them? What does something that’s quickly typed out on a keyboard – ‘she interpreted between Cortés and the Mexica’ – look like in real life? And how did it feel to navigate such a diverse soundscape, where a single misunderstood word or phrase could lead to death and destruction?

Relatively few details are known from Malinche’s life, and there is no direct record of her thoughts. However, we know quite a lot about the languages that shaped her. Among them are different varieties of Nahuatl and Maya, two language families that are deeply intertwined with the culture and history of Mexico before the conquest.

Through these languages, and their broader history, we can at least partly reconstruct how an anonymous girl from a riverside hamlet near the Gulf of Mexico came to be the voice of the Spanish conquerors.

From Languages Are Good For Us (Apollo, £18.99)

Sophie Hardach is the author of three novels, The Registrar’s Manual for Detecting Forced Marriages, about Kurdish refugees, Of Love and Other Wars, about pacifists during World War Two, and Confession with Blue Horses, about the repercussions of the division of Germany on the lives of individuals. Also a journalist, she worked as a correspondent for Reuters news agency in Tokyo, Paris and Milan and has written for a number of publications including the Guardian, BBC Future and The Economist. Languages Are Good For Us is published by Apollo, an imprint of Head of Zeus, in hardback and eBook.

Sophie Hardach is the author of three novels, The Registrar’s Manual for Detecting Forced Marriages, about Kurdish refugees, Of Love and Other Wars, about pacifists during World War Two, and Confession with Blue Horses, about the repercussions of the division of Germany on the lives of individuals. Also a journalist, she worked as a correspondent for Reuters news agency in Tokyo, Paris and Milan and has written for a number of publications including the Guardian, BBC Future and The Economist. Languages Are Good For Us is published by Apollo, an imprint of Head of Zeus, in hardback and eBook.

Read more

sophiehardach.com

@Sophiehardach

@HoZ_Books