Laura Lippman: No more heroes

by Mark Reynolds

“Engrossing, suspenseful and substantial.” Scott Turow, The New York Times

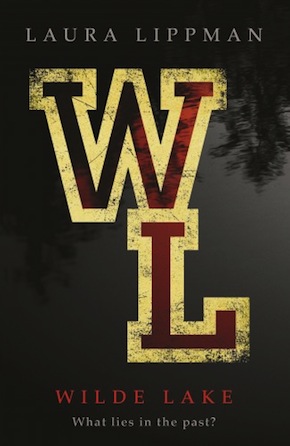

Laura Lippman’s latest novel is set in the Maryland suburb of Wilde Lake, Columbia, twenty miles west of Baltimore, where she lived and went to school in the 1970s. The ‘new town’ of Columbia was founded as a well-meaning experiment in egalitarian community living – which in retrospect was always likely to fail. With deliberate echoes of To Kill a Mockingbird, Wilde Lake is constructed around an accusation of sexual assault and features a protagonist who grew up believing her attorney father to be an unimpeachable hero.

MR: What led you to approach the themes of such a well-known book from a more contemporary perspective?

LL: It’s kind of a roundabout road. I was very interested in what in the States is called ‘rape culture’. I don’t like the term; it sounds a little bit nicer than it should. I’d written one very short novella about a real-life incident, and then Dylan Farrow, the daughter of Mia Farrow and Woody Allen, published a letter in The New York Times asserting, “Yes, I was the victim of a sexual assault by my father, and it is important to me to say that directly and clearly, and make sure that people don’t think this is an allegation that was made on my behalf by my mother.” I was very moved by her letter, and I think a little bit chagrined looking back at when the case had first come to light, that I’d had a kind of cynical, world-weary, “he said, she said…” response to it. I then went and read every primary document, every legal finding in the case, and things were not quite as I’d remembered them. For example the prosecutor very much wanted to pursue a criminal case against Woody Allen, and declined only because he and Mia Farrow believed that Dylan would be damaged by a trial. That’s very different from no charges being filed because the case was unfounded. And I decided, just for myself as a human being – not as a journo, not as a cop, not as a judge – that maybe when people say they’re raped I’ll just believe them, because most people don’t lie about it.

In the United States we have reliable statistics that false accusation accounts for between 2 and 8 per cent in rape cases that go into the criminal system. Of course you do not want to be one of the 2 to 8 per cent who is falsely accused of rape, but the problem of rape is much, much larger than the problem of false accusation. Sure, there were cases that did turn out to be false, but I didn’t feel any worse for having believed the person until they were proved wrong.

Having thought this way about real-life cases, I began thinking about how rape had been handled in film and literature, and again the idea of false accusation is much more prevalent in fiction than it is in real life. And I looked at To Kill a Mocking Bird, this book I love so much, and thought, so do we now doubt the events? Can we believe Mayella and Ewell? Obviously To Kill a Mocking Bird is a book of its time and place, it’s about the 1930s in the United States, it’s about how racism is so ingrained that a clearly innocent man would be found guilty. But what if you take those situations and bring them forward? What if we are now talking about people who think of themselves as much more evolved in their attitudes towards race and sex and gender? Today most well-intentioned people understand that rape occurs when a person has sex without consent. But then I thought, what about the 1970s, when people were almost self-congratulatory in their liberalism? And having thought about the 1970s I thought about the place where I went to high school, which happened to be this extremely progressive suburb that had this real kumbaya vibe, and I said OK, that’s the book, that’s the story: just take the broad outline of To Kill a Mocking Bird, but take it to a different place, and especially to a different time.

There’s something eerily cool about the fact that Harper Lee also struggled with the idea of Atticus as purely heroic. Of course, what’s the key difference between the two books? One is told by an adult and one is told by a child.”

You make it clear how difficult it is these days to lionise or idolise public figures, whether from the past or from the present. And after Go Set a Watchman, we’re now reassessing the hero status of Atticus Finch as well. What are your feelings on the release of that book, and its effect on the reputation of Harper Lee, and perhaps of the publishing industry too?

Go Set a Watchman was published by my publisher in the States, HarperCollins, and two men were instrumental in making that happen. One of them is Jonathan Burnham, whom I know not at all, the other is Michael Morrison, whom I hold in very high esteem and consider a friend. So I believe and trust Michael’s explanation that this was something that Harper Lee wanted. I do believe that Go Set a Watchman should be in the public domain, that it’s something that should be available to readers, and I think it’s certainly important for scholars and for students of literature to have this version of the story. I’m pretty convinced, primarily by a very good article written by Neely Tucker in The Washington Post, based on records from the literary agency, that they are two sides of a coin. Still, it’s fascinating. Go Set a Watchman came to light while I was in the middle of writing my book, and it was published last summer at almost the exact moment I handed in my manuscript. I got one of the first copies in the United States because my publisher sent it to me, and I had to not read it. I was like, I’m going to read this not only after I’ve finished Wilde Lake, but after I’ve finished talking about Wilde Lake. I don’t want it inside my head.

There’s something eerily cool about the fact that, no matter what the sequence of events is, Harper Lee also struggled with the idea of Atticus as purely heroic. Of course, what’s the key difference between the two books? One is told by an adult and one is told by a child. The child lionises her father; the adult has to come to terms with the reality of her parent. That’s just life, that’s how it works. If indeed Go Set a Watchman is the first book, it was a very canny choice of editing to switch to the child’s voice because it allows you to avoid thorny questions about Atticus’s character.

There’s some funny instinct at work that I kind of did the two things in the same book; here’s the child and here’s the grown-up. Sometimes things are just in the air and you’re going to see a lot of people grappling with them. And it’s not just that we are reconsidering Atticus Finch. People in New Orleans voted to take down statues of confederate war heroes because they’re on the wrong side, but in the same city there’s no way they’re going to get rid of the statue of Andrew Jackson, because he was the hero of the Battle of New Orleans. But Andrew Jackson is certainly as problematic a figure in history.

What I find interesting – it’s even a line in the book – is that we keep thinking we’re done. It’s like we’re so smart and evolved that we’re not making any mistakes anymore. We look at all those poor ignorant people in the past who didn’t have the right ideas about race and the role of women, and we act as if in twenty years people aren’t going to be saying the same thing about us. It’s in the air, it’s of the moment and I’m just one person among many picking up the signal.

About halfway in, state’s attorney Lu Brant writes: “The truth is messy, riotous, overrunning everything. You can never know the whole truth of anything. And if you could, you would wish you didn’t.” She’s aware that she’s on the verge of shattering discovery – but she’s also withholding secrets of her own. She’s a public investigator who wants to keep parts of her own life private, and who it turns out has been told some huge lies by her family. How did her character develop; and why was a state’s attorney the figure through whom you wanted to explore your themes?

In To Kill a Mocking Bird, Atticus is famously a defence attorney, but I’m very interested in the problems that flow from people thinking themselves to be well-intentioned, and I decided early on that it would be so much more interesting to be dealing with prosecutors. Defence attorneys focus on a single client, their job is, case by case, to defend the client to the best of their ability. They’re not particularly interested in the truth, that’s not their job. Their job is to provide the best legal defence for the client based on the facts at their disposal. They’re not to disregard difficult facts, although many defence attorneys make the decision that the client should not take the stand if that person has committed other crimes because if a person never takes the stand, the jury does not get to hear about any criminal record.

So I really wanted to have these two generations of people who believe themselves to be on the side of truth, of the big picture, who have to produce the whole story that establishes guilt. And I wanted all the contradictions of a public figure with a private life, the truth-teller with her own secrets, the noble public servant with the messy private life. I’m so interested in sanctimony. I’ve always been fascinated by people who believe themselves to be so good that they’re beyond reproach, and there are a lot of people in this novel like that.

This is a long-standing obsession with me. I’m not interested in villains, I love writing about good people who do bad things, and still think themselves good.”

I was a reporter for twenty years, mainly a feature writer but I did hard news too, and I had this long spell of time when I covered poverty in Baltimore, which also meant that I covered the non-profits that served the poor. There was this woman in Baltimore called Bea Gaddy, who was known as the Mother Teresa of Baltimore. She had famously started feeding the poor on Thanksgiving after she won the lottery. I had no suspicion of her, I just wanted to write about her, and I began doing that fly-on-the-wall thing where I followed her around all the time. It was appalling! The woman, in my presence, in the presence of a journalist, opened up all the cheques one day and sent one of her volunteers to a cheque-cashing store to cash them – so first off she’s paying 17 per cent off the top. She used part of it to pay her electric bill and her private phone bill, and then she told one of her workers to go buy lottery tickets. My bosses did not believe me when I came back with what I had. As a matter of fact they were desperate not to publish the story because she was a saint and she was African-American, probably the single worst person to write an investigative piece about in Baltimore, and they tried to bury it. They published it on a holiday weekend, when no one would read it, but it got her audited by the IRS – and also earned me an enemy for life.

So you didn’t take Bea off the streets altogether. Is she still out there?

Bea has passed on, and Lord knows what kind of mess she left behind. Over the years, other reporters would interview her and she’d go off on me every time, but she still thought of herself as good. She wasn’t walking around saying, “I’m a gangster, I’m ripping the system off.” She was like, “I’m a saint, and I do good things. How can anyone question the way I go about doing these good things?” So this is a long-standing obsession with me. I’m not interested in villains, I love writing about good people who do bad things, and still think themselves good. I’m talking about my own characters now, the stories they come up with to tell themselves that everything they’ve done is OK.

The book is told in two voices, switching between Lu’s journal of her childhood and a third-person, present-day narration – in which Lu is also a strong presence.

It’s also her pov, but present tense. It was really hard to figure out how to write this book. I’d written so many novels from multiple points of view, I’d played with time a lot, and I’m really intent on not repeating myself. The writers I admire most are people who have written really different books. So I want to keep challenging myself, but I also want to do what’s best for the book, you can’t do what’s easiest. At this point I think I could do multiple pov in my sleep, it could’ve been: here’s Lu, here’s AJ, here’s Bash, everybody telling pieces of the story, and it’s easy to create suspense because you move from character to character and they can only know what they know.

But this is so much Lu’s story, for some obvious reasons by the time you get to the end, and it’s a book that’s obsessed with the past and the present, and how the present will reconcile itself to becoming the past. And I thought, OK, there should be these first-person, past-tense passages that suggest someone who knows the whole story, and then when we see her in the present day it should be in the present tense through a third person because that illustrates the folly of thinking you ever know anything.

We’re living in the moment, and if ten seconds from now there’s a loud explosion, there’s no foreshadowing to that. We live in the present tense, to say the obvious, and I wanted to capture Lu in the present: smart, good at her job, she has all of this history that the other Lu tells us, but still she doesn’t see what’s coming. But then the trick was, OK, but at some point it has to end, at some point the two have to come together, and when is that going to be? And I just had to write my way to that, to find the point at which we now only have present-tense Lu. And then the question was, will past-tense Lu come in at the end to sum everything up for us, and what will that feel like? And it felt right to me.

Is the Baltimore depicted across all of your books recognisably the same city? Is there a sense that Tess Monaghan could cross paths with Lu?

She could. It’s twenty years since I started writing books and Baltimore has changed in a lot of ways, but because much of this book is in a suburb of Baltimore I don’t really touch on it. There is that moment when Lu goes into the city to attend a viewing at a funeral home, and there are little hints about how the neighbourhood around her is changing. She’s actually standing across the street from my daughter’s Montessori school, where there’s this gargantuan tower block going up that’s so out of scale for the neighbourhood. At the turn of the twentieth century, this was a working-class neighbourhood for people who worked around the port. It became pretty super-gentrified from the 1990s on. But who am I to complain? I’m one of the gentrifiers. But now these millennials are coming in who want their high-rises. I said to my husband [The Wire creator David Simon], I think there’s a tipping point between us and the millennials – and they might win. I mean, right now it’s a remarkable story of revitalisation. I moved into this neighbourhood twelve years ago and there was literally one school-age child on the block because people moved in, had kids, moved out. People could not send their children to Baltimore City public schools, they moved to the suburbs. Today, within a four-block radius, there must be fifty children, and our daughter is going to go to a public school in our neighbourhood in the fall, and it’s a good school. This was unthinkable a decade ago. So yeah, it’s a recognisable Baltimore. But it’s only one part of Baltimore.

One of the things I was asked about a lot over the past year is, “So when are you going to write about Freddie Gray?” – the black man who died in police custody in April 2015.

He does get mentioned in your book…

Yeah, there’s a tossed-off line about how police were obligingly killing black men all over the United States at this time, and unfortunately that continues. But I can’t tell the Freddie Gray story except from the perspective of a white person looking at it. I suppose I could be really ambitious and attempt to write the story of Freddie Gray’s life, and I’d certainly consider anything on the table in terms of my imagination, but I don’t think I would execute that well. Now the trials are going on, they haven’t managed to convict a single person. Three ended in acquittal and one ended in a mistrial. There probably is somebody in that group of officers who could’ve been held criminally accountable for the death of Freddie Gray, but the charges were too big, and the charges were brought to make people in the community feel better, which is not how you should do the job of being a prosecutor, you have to bring the right charges.

So it’s a recognisable Baltimore, but it’s the Baltimore that’s seen primarily by a middle-class, middle-aged white woman.

How would you characterise the community of Wilde Lake, Columbia, then and now?

It’s a very different place now. At that time, from its founding in ’67 through the ’70s it had… I wouldn’t say a hippy-dippy vibe, although parts did, but it was extremely liberal. People were true believers. My friends were the first kids to come all the way up through local schools from the age of 6 to 18, and their parents believed in the concept of Columbia. It wasn’t just a convenient place to live between Baltimore and Washington, these were self-selected pioneers. And it just didn’t work.

First of all the educational system didn’t work because teenagers are just probably not well suited to that much freedom. They’re not self-starters, they’re not going to get their work done, so that part didn’t work so well. And then I think they found that a lot of people didn’t embrace the idea of a class-free development, people didn’t want to live next to the Section 8 housing.

Columbia founder James Rouse (left) unveils a plaque honouring Connecticut General president Frazar Wilde (right) with the naming of the new town’s first lake in 1967. Columbia Association archive

Columbia has continued to spread over the years, and in one of those serendipitous things, my stepson who just graduated from college also grew up there. He and his mom lived in the far west of Columbia, in the most desirable school district, where the houses were McMansions and affordable housing meant a townhouse that cost $300,000. There was racial diversity in that there were a lot of Asian-American kids at the school, but fewer and fewer African-American kids. So it really lost touch.

The people who grew up there are crazy about it, and it really does have a Facebook page called ‘You know you grew up in Columbia when…’ and everyone on the page, to the extent that I’ve checked it, has been pretty nice about the book. Some of my friends who grew up there were really helpful to me in writing the book, and one of them reached out to me after the book came out and said, “You know, we really did think we were so evolved on the subject of race, but I look back now and I don’t see it that way.” And I said, well I think we were evolved on the subject of race in terms of we didn’t see difference. But one of the funny things about this ‘don’t see difference, nobody’s different’ idea is that when there were African-American students in our high school who wanted to embrace a very particular African-American identity, whether we’re talking about clothing or music or wearing a hair pick that had a Black Power fist on it, which was really something in the ’70s, people didn’t like that. It was like, “No we’re all the same, that’s the whole point of Columbia, there are no differences.” So people who sought to have an identity that was very much about difference and individuality, especially when it was expressed through being African-American… or God knows what would’ve happened if someone had tried coming out as gay. I’m sure that no one in my high school was out as gay. I can look back and think of who probably did end up coming out, but no, it wasn’t that progressive.

So I think it was a really beautiful, unworkable idea. The thing that makes me angriest when I go back is that Columbia had a lot of dedicated green space, and I’m pretty sure they’ve built on a bunch of it. I don’t even live there anymore and it pisses me off. So it’s a different place, but isn’t every place different almost thirty years later?

Sure, and it can be argued that those kinds of genuinely radical, progressive values and social experiments have since been replaced by anodyne, knee-jerk political correctness – which opens a door for populist anti-establishment figures like Sarah Palin or Donald Trump to spout the opposite view.

I think what we’ve been seeing, and it’s actually been going on for over a decade, is there are a lot of white people who were just fine with how everything was, because they were resting on the idea that they were going to forever be in the majority. With the rise of immigrant populations in the United States, the statistical reality is that at some point whites will not be the majority – they’ll be the plurality, they’ll still be the biggest group of people, but not the majority – and as that idea starts coming into reality, it comes at an emotional, psychological cost to a lot of people. I’ve had liberal friends, smart, progressive people, who left the city of Baltimore because they were disturbed by the fact that their child was going to be in classes that were majority African-American, saying “I don’t want my kid to be in the minority.” And I think, Did you hear what you just said? If it’s not good for your kid to be in the minority, then it’s not good to be in the minority. But someone has to be, right?

Between you and your husband, do you overstate or accurately depict the rate of crime in Baltimore?

Oh, I think we’re both pretty accurate about it. But here’s the irony, I’ve written more than twenty crime novels, and the standalones tend to take place in the suburbs, but even if you just look at the 12 Tess Monaghan novels, which are all set in the city, those are fake, because they are all about what the police call ‘red balls’. There’s only one novel that I wrote that’s about how crime really works in Baltimore, which deals with the deaths of young African-American men. But my books are mostly fake as crime fiction tends to be, because you write about the cases that almost never happen. They could happen, but they’re not the day-to-day reality. So my books are realistic and they’re credible, and sometimes they’re even inspired by true crimes, but the true nature of crime in Baltimore is the kind of soul-deadening, day in, day out, drugs were being dealt on the corners, another corner boy got shot… The Wire is actually super accurate about crime in Baltimore, and the type of crime in Baltimore. So I give him higher points for accuracy. You know, there are people in Baltimore who are always trying to make out that The Wire affected Baltimore’s reputation. I just don’t think that’s true. I think people are smarter than that, and I think people know that it’s not the whole story, but still some guy’ll come along and say. “I wanna promote the positive.” And somehow I get completely left out of the debate. People think I’m good for Baltimore because, I don’t know, I talk about certain food and folklore. I don’t even understand that disconnect. I mean, I’m killing people too!

You also appeared in one episode of the show…

As myself – and I garnered some of the worst reviews of my life! It was season 5, which remains a controversial season, and some people who reviewed it decided that me playing myself was emblematic of what was wrong with it. So I was singled out, which I really find quite ridiculous, that anyone would care about my one-line reading of “Hey, I’m not the police reporter.” It couldn’t possibly have been as bad as they said. There are a lot of real-life cameos in The Wire, and I’m in the dead middle. I’m not the worst, I’m not the best. But yeah, that happened.

Laura Lippman spent twenty years as a reporter, including twelve years at the Baltimore Sun. She began writing novels while working full-time and published the first seven novels about Baltimore City’s ‘accidental PI’ Tess Monaghan before leaving daily journalism in 2001. She has since added five more books to the series, and written nine standalone crime novels. Her work has been awarded the Edgar, the Anthony, the Agatha, the Shamus, the Nero Wolfe, Gumshoe and Barry awards. Wilde Lake is published by Faber & Faber. Read more.

Laura Lippman spent twenty years as a reporter, including twelve years at the Baltimore Sun. She began writing novels while working full-time and published the first seven novels about Baltimore City’s ‘accidental PI’ Tess Monaghan before leaving daily journalism in 2001. She has since added five more books to the series, and written nine standalone crime novels. Her work has been awarded the Edgar, the Anthony, the Agatha, the Shamus, the Nero Wolfe, Gumshoe and Barry awards. Wilde Lake is published by Faber & Faber. Read more.

lauralippman.net

@LauraMLippman

Author portrait © Lesley Unruh

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer and a founding editor of Bookanista.

@bookanista