Lisa Harding: Lost lives found

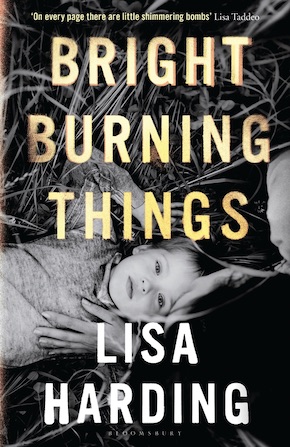

by Farhana GaniSonya, Tommy, Herbie and Marmie. These four characters have embedded themselves into my psyche. The last time I cared so deeply about the fate of fictional creations was with Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life. Where Yanagihara’s doorstopper spanned decades in the lives of four men, Lisa Harding’s blisteringly brilliant novel Bright Burning Things takes place within a year in the life of a young Dublin-based woman named Sonya, and her household.

From the opening pages we learn Sonya is a drinker, a heavy drinker. A young single parent who gave up a promising acting career, she adores her four-year-old Tommy, and loves her rescue dog Herbie (“who rescued who?”). After her own difficult childhood – she was bullied at school and distanced from her father, who remarried a woman she didn’t get on with after her mother died – Sonya tries to put a protective ring around herself and “her boys”.

She also avoids consuming anything that requires animal suffering: “Cow’s milk? Disgusting. What mother in her right mind…? The calves cry themselves hoarse.” The thought of eating meat sends her into the depths of despair. It’s one of the reasons why she hates food shopping, “aisles of dead animals” – but that doesn’t stop her from shoplifting bottles of wine.

Like so many addicts, Sonya may have the best intentions towards those who depend on her but loses any semblance of self-control in her desire to sate her senses. Prone to paranoia, she aggressively resists any offers of help, seeing them as a personal attack on her capabilities. When her capacity for self-harm spills out and begins to hurt Tommy and Herbie, she is horrified. She knows she must change her life or risk losing everything.

A catalyst for this process is Mrs O’Malley, her curtain-twitching neighbour, who, fearing that Tommy is being neglected and malnourished, threatens to report Sonya to the Guards. It turns out Mrs O’Malley is being paid to be nosy by Sonya’s estranged father, who stages an intervention and forces Sonya to agree to a 12-week treatment plan. The rehabilitation centre, run by nuns, is situated outside Dublin, and she undergoes a tough drying out regime, in which she isn’t allowed any contact with Tommy for the first few weeks. Sonya believes he’s now in the care of her father.

Sonya’s battles for herself and her boys are only just beginning.

Bright Burning Things is a story about addiction, motherly love and how society at large handles ‘difficult’ women. It is so tightly written, reading like a thriller in which you need to know what’s going to happen to sweet boy Tommy, trusting Herbie and tortured Sonya. Harding cleverly weaves in everyday events, to paint a picture of disorderly existence in these modern times. Surrounded by consumerism, the me-first generation, climate change, animal welfare, and codes on how a mother should be, it’s no wonder that addiction and mental health issues are taking centre stage.

Farhana: Tells us about your lockdown experience, including the impact it has had on your daily life, and your reading and writing.

Lisa: At first I was very productive, thinking it would give me time to focus only on writing, and I wrote a first draft of a new novel in six months. Then life and anxiety took over and I have found it hard to concentrate on either reading or writing in this second prolonged lockdown. I am watching too much Netflix!

How long did you work on Bright Burning Things, and what was your writing regime?

I worked on-and-off for three-and-a-half years. It was a hard book to get right as it’s so raw and it changed form many, many times. I tend to write in obsessive spurts and then watch too much TV in between.

My experience of loving an alcoholic is that parenthood can be a dangerous, volatile territory for the child in the situation. Alcoholism rarely exists separately from mental health issues or a history of trauma.”

The book covers many themes, from motherhood and addiction to mental health and animal welfare. How did it come about?

I have personal experience of loving someone in my family with a chronic addiction to alcohol. It has been such a destructive force not only for the person in the grip of the addiction, but also all those around them. My experience of loving an alcoholic is that parenthood can be a dangerous, volatile territory for the child in the situation. Alcoholism rarely exists separately from mental health issues or a history of trauma. I learned a lot about ‘dual diagnosis’ over the years and my character certainly suffers with this. Her intense love and concern for animals is a way of her trying to channel her extreme emotions. Animals are, after all, a lot less complicated and easier to love than human beings, especially if, like Sonya, humans have caused a lot of harm.

The treatment programme Sonya undergoes for her alcoholism is brutal, particularly her prolonged separation from Tommy. How did you research this?

The person I love who suffers with alcoholism has spent many, many stints in this particular institution in Ireland, run by a religious charity. I wanted to highlight the fact that there is no state-run facility in Ireland and people who have no health insurance or ability to pay for expensive private rehabs have no choice but to enter a religious rehab like the one in the book. I met many mothers over the years of visiting who had similar experiences to my character. The separation is very, very hard, but also unfortunately necessary at a certain stage in the addiction process. My research was all based on first-hand experience.

You suggest there is a link between mental health and how we treat animals. Sonya is particularly affected by cruelty and inhumanity in the meat and dairy industries – there’s a parallel between dairy cows separated from their calves, which Sonya despairs about whenever she’s offered dairy products, and her own separation from Tommy. Why was it important for you to shape her in this way?

That’s a really interesting observation and not one I had consciously recognised myself as I was writing this novel. But no doubt Sonya is very moved by animal cruelty, and it can be a source of great pain for her. She feels overwhelmed with all the suffering in the world, and focusing on animal mistreatment is a part of her negative mind-looping. It is also a part of her great ability to feel compassion and empathy for voiceless creatures. That she gets separated from her son is agony for her. When she cries thinking about the calves separated from their mothers in the dairy industry, I must have unconsciously echoed that.

Sonya has given up her blossoming acting career for motherhood, and she finds herself unable to cope as a single mum surviving on social welfare cheques, and drowns herself in drink. She struggles in this new role without a script, having to ad-lib with disastrous results. Sonya is experiencing a form of shock at her new reality, isn’t she?

Yes, that’s very well articulated. I think motherhood is a huge shock to Sonya. When her acting career is removed, where does she channel her manic impulses, her creative charge? She uses alcohol to both try to soothe herself and recreate the highs of her former career that she misses on a cellular level. She is very alone and adrift in her new reality as a single mother.

I didn’t want to shy away from the harsh reality of being an alcoholic mother, and also I wanted to express her humanity, her heart, her love, compassion, humour.”

Sonya is angry and distrusting, she neglects her child’s welfare, she is reclusive, she suffers dangerous alcohol-induced blackouts. In summary she sounds like a nightmare, but you show her gentle heart, free spirit and vulnerability. How did you balance out her dark and light?

Thank you for saying that. I worried she might be too dark and too destructive for some readers. The fact that I love an alcoholic, despite the chaos and hurt they have caused in my own life, allowed me to access this compassion for Sonya. It is not an easy place to be: living with that constant voice in your head that tells you to pick up, pick up. That battle is terrifying and very real. I didn’t want to shy away from the harsh reality of being an alcoholic mother, and also I wanted to express her humanity, her heart, her love, compassion, humour. I love that you call her a free spirit. I think she is; I just think she needs to find a way to bring all those parts of herself to bear. No one is ever only one thing.

Tommy is a bright, imaginative little boy. He cares for his animals so kindly and sweetly. He also develops a means of self-preservation as events conspire against him. You’ve created a lovable child only a heard-hearted reader wouldn’t want to care for. That’s an incredibly powerful thing for a writer to achieve. How did you shape his character?

I love that little boy and felt so protective of him writing this. Not an easy thing: being the child of an alcoholic. And he is so alone, except for his best pal, the rescue dog Herbie. I’m dog-mad myself and growing up we always had big, beautiful dogs who would soak up a lot of tension in the house. They can be incredibly stabilising presences for children in stressed environments. Little Tommy is resourceful, imaginative and resilient. He has to be.

Herbie and the rescue cat Marmie she adopts later on are beautifully drawn too – you obviously live with animals…

Yes. I am animal-mad for all the reasons I’ve written about already. Their innocence and purity. They teach us about being better people (in my opinion), and if I let it in like Sonya I too can get overwhelmed by how badly we treat our fellow creatures. There does seem to be a counter-movement now towards recognising they are sentient beings, which is soothing and hopefully signals a better future for all animals at our hand.

Sonya’s counsellor David Smythe is a controlling, imposing character whose presence introduces an element of psychological thriller to the novel. There is a creeping tension and looming sense of menace whenever he makes an appearance. He’s a piece of work, isn’t he?

He is a piece of work. He’s a composite of men I have let into my life, as well as two friends’ separate experiences with their counsellors. Imagine breaking that boundary. What an abuse of trust. That coercive control: it’s so insidious and dangerous and very hard to see until you’re out of it. Sonya is vulnerable and doesn’t trust her instincts when she meets him. He senses that and abuses her trust.

During Covid I wrote my first psychological thriller. They are as fun to write as they are to read, and I think we all need a bit of that right now.”

How has your training and performing as an actor informed your writing?

I think it has absolutely made me the writer I am: internal, voice-driven, immersive, first-person monologic. I write from the inside out, like how I approached my characters as an actress. I guess I’m a method writer!

Are there any plans afoot for Bright Burning Things to be adapted for screen? Who would you like to see cast as Sonya?

Yes, it has already been optioned but I can’t say any names yet. I adore the Irish actress Jessie Buckley and think she would make a brilliant Sonya. She’s capable of such truth, dexterity and complexity.

Tell us about your own reading habits. Which recent books would you particularly recommend?

I just finished Shuggie Bain, which some people have compared my book to. I loved it. It’s very different to how I approached the narrative of the alcoholic mother, as it’s told in a third-person voice from the perspective of the son. A beautiful, heartbreaking book that deserves all the plaudits. Also, I got an advance copy of Animal by Lisa Taddeo, which is remarkable. I love how she writes. It’s visual, pacy, funny and sharp.

Any cultural highlights for 2021 you’re particularly looking forward to?

It all seems like an abyss right now! I hope and pray we can all get back to some semblance of normal life soon. I would love to participate in some literary festivals this summer, but who knows? I’ve been invited with the book to New York in December, so fingers crossed for that.

Both Harvesting and Bright Burning Things tackle sensitive social issues that are often underexposed. What are you working on next?

I have gone a little less intense with novel number three. I think I had to, for my own mental health. During Covid I wrote my first psychological thriller: a sort of cult campus novel. Not light exactly, but not as intense and interior as the other two. Novel number four will be a return to form. I already have the bones of an idea expanding on the idea of coercive control in a relationship. For now, though, I’m enjoying writing my twisty, turny thriller-esque novel. They are as fun to write as they are to read, and I think we all need a bit of that right now.

Lisa Harding is a writer, actress and playwright based in Dublin. Her previous novel Harvesting, which gives voice to victims of sex trafficking, was a bestseller in Ireland, won the Kate O’Brien Award and has been optioned by Out of Orbit Films, with Michael Lennox (Derry Girls) attached to direct. Bright Burning Things is published by Bloomsbury in hardback and eBook.

Lisa Harding is a writer, actress and playwright based in Dublin. Her previous novel Harvesting, which gives voice to victims of sex trafficking, was a bestseller in Ireland, won the Kate O’Brien Award and has been optioned by Out of Orbit Films, with Michael Lennox (Derry Girls) attached to direct. Bright Burning Things is published by Bloomsbury in hardback and eBook.

Read more

@LisaSHarding

@BloomsburyBooks

Author portrait © Francesca Mantovani

Farhana Gani is a freelance writer and a founding editor of Bookanista.

@farhanagani11

@bookanista

wearebookanista

bookanista.com/author/farhana