Love, judgement and forgiveness

by Mika Provata-Carlone

“Full of insight and intrigue.” Observer

“Children begin by loving their parents. After a time they judge them. Rarely, if ever, do they forgive them”, said Lord Illingworth to Mrs Arbuthnot in A Woman of No Importance. It is perhaps one of Wilde’s most chilling aphorisms, as much a witticism à clef, as it must have felt like a presentiment and fear foreshadowing Wilde’s equally chilling future.

Colm Tóibín is keenly interested in families, in the ineffable bonds that render them the be all and end all, or the binds that tether and shackle, and that have inspired the greatest dramas on the page, the stage and the hearts and minds of endless generations. It is no coincidence that one of his previous collections of essays bore the darkly titillating title New Ways to Kill Your Mother. He is also audaciously curious about genealogies – false or genuine paternity and maternity, the meaning of it all, whether on the level of the human sentiment or in the depths of the words that we seek in order to express this continuity with and separation from all that we are or hope to be.

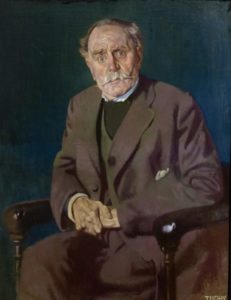

In Mad, Bad, Dangerous to Know: The Fathers of Wilde, Yeats and Joyce Tóibín brings together the essence – and even the orality and timbre – of the Richard Ellmann Lectures in Modern Literature he was invited to deliver at Emory University in November 2017. On the surface, it is an obvious choice of subject – Wilde, Yeats and Joyce are the three Irish Greats, the Fathers of Irish Letters as we know them, perhaps even of the Irish heart and mind as it would like to imagine and define itself. The gesture of taking a step further back to look at the progenitors of these monumental father figures is also on the face of it predictable. Portraits of William Wilde, John B. Yeats and John Stanislaus Joyce have been attempted before, with various degrees of accuracy and celebrity. Yet what Tóibín sets out to do is considerably more complex, ambitious and ultimately thrilling.

Dublin emerges as the breeding ground of both good and evil, shock and wonder, explosive visionaries and more quietly eccentric geniuses.”

In his hands, fathers and sons become both text and pretext; they provide the most opulent occasion for what Tóibín does best, namely seamless, flowing narrative and storytelling, and the excuse for a veritable ode to Dublin, to the living historicity of Ireland and the Irish, to the impossibility, even, of ignoring the past or neutralising the present. There can be no Ireland, no Irishman or Irishwoman without memory, its burden, its breathing sharpness, we seem to be told on every page. In Dublin, as Tóibín sees it and revisits it, as he perhaps creates it, at every turn and unsuspecting instant “the mind pondering on nothing much or the malady of the quotidian, can become bothered by heroes, by history, by head-bangers”. He ought to know. He comes himself from rather formidable stock.

Dublin emerges as the breeding ground of both good and evil, shock and wonder, explosive visionaries and more quietly eccentric geniuses. As a tapestry woven out of the atemporal or the merely ephemeral, but also as a web that captures lives, links them inextricably, no matter how much they tug and struggle to break free. His Dublin is a destiny and a fate, but it is not a place of departure or a destination. You cannot leave Dublin behind, nor can you arrive there as a newcomer. A Dubliner is, cannot become, nor can they be unmade. A Dubliner invariably, like Beckett’s characters, does ‘nothing much’, and yet that mere nothingness is enough to bedazzle and transfix the world, or so Tóibín would have it. Let me tell you the tale of Dublin and Ireland, he seems to say – of its heroes and scoundrels, the bloodiness and the blessings, above all of its love for paradoxes, topsy-turviness, radical reversals and transgression. The tale has all of Tóibín’s brilliance, as well as some of his hallmark failings, such as for instance the conviction that the close microfocus on the authorial ‘I’ is always necessary and revealing, an axiomatic perspective of analysis, or the enamoured emphasis on a verbal fluidity that on occasion may become corpulence.

This is a book especially about connections, whether fecund and full of promise or jarring, a heavy burden or an unwelcome, inescapable attachment. The Yeats and Wilde families were part of the same Dublin world; Joyce would feel the need to create the connection of the missed link between his own more troubled family and theirs by caricaturing both Wilde and Yeats in Ulysses. It goes to show how very close and how remote to one another they were. Yet the city and the country do not allow for separate lives, a theme Tóibín has picked up repeatedly in his novels. “A set of networks and webs of association began to evolve in the city, intensifying the narrative and making it more mysterious, offering the atmosphere here in Dublin a hidden and powerful underflow… that politics did not offer, nor commerce either.” The lives of artists, writers, thinkers possess a power beyond worldliness or perhaps even humanity.

The unspoken theme is the vital art of creation that transubstantiates merely being alive into being. And the highest form of such creation, at least in the context of these writers, certainly so for Tóibín, is reading not only the words but the voice, the gaze behind them. Literature is the indispensable filter for understanding and belonging to the world, as well as what forges individual consciousnesses, separateness, an almost valorised ‘aloneness’, as he calls it. As he visits the National Library, he hears “a sudden pounding silence, as heads are bowed low in the holy sacrament of reading.” This is a book about writing and reading, about authorship as much as it is about paternity and filial influence or tension. It is about the paternity of Irish literature, Irish identity, the legitimacy of Ireland itself as a nation, and, perhaps much more crucially, as a topos.

There is an alluringly rich array of historical and personal anecdotes and experiences, such as his reading of De Profundis while locked up in Wilde’s cell in Reading Gaol, and a surfeit of truly riveting close readings and cultural analyses. Characters both minor and major emerge with the haphazard naturalness of an encounter, a meeting that is so much more than a simple crossing of paths. These three almost supernaturally larger than life figures had universes of even larger, more Gargantuan proportions of their own, and Tóibín takes particular delight in painting the dazzling details as well as the garish hues of his multifaceted, ever-shimmering mural. Stories of loneliness, ingeniousness, extraordinariness or scandal vie for space or intersect, evoking the rather wondrous sense of being in the presence of a storyteller-mystic at the height of the methectic trance.

Tóibín shares liberally his powers of inwardness and otherness, insights on the self or the society of lives and minds. We have a privileged view of his lightness, mirth and sadness, mischief, and distinct sense of duty to wisdom.”

The counterpoint of this is that sometimes there is too much emphasis on what emerges as the social dysmorphia, the almost garrulous extravagance of each set of parents (and even sons), the inclination of the age for a hyperbole in relentless tension with almost ascetic restraint. Yet what redeems this compulsion to tell all is Tóibín’s receptivity as an interpreter, as a filter and guide. “Sometimes in the great unsteady archive where our souls will be held, there is a special section that records the quality of our gaze” – a sentence and pronouncement that evinces the rare human sensibility he has sought to develop and nurture in his work and in his public life. The notion of the gaze, both as a relationship, but also as a gesture of totality and dominion, allows him to launch upon a close, shrewd and evocative reading of Yeats’ poetry, of his own parental burdens and resources. It will also endow his reading of Joyce’s work, his life story and the creations of his mind, with unmissable discernment.

In Mad, Bad, Dangerous to Know Tóibín shares liberally his powers of both inwardness and otherness, his insights on the self or the society of lives and minds. We have a privileged view of his lightness, mirth and sadness, mischief, certainly, but also of his distinct sense of the duty to wisdom that has come to be his intellectual trademark and calling. This is a book as much about the Wildes, the Yeatses and the Joyces, about fathers and mothers, sons and daughters, as it is about the creation of lives and genealogy, about history and destiny, about Ireland and the (re)creation of a nation. It is about spiritual journeys and vocational paths, art and science, a life of the mind and being in time. Ultimately, it is about defining a life worthy of living, and Tóibín traces the many options of such an itinerary with engrossing indulgence and clarity.

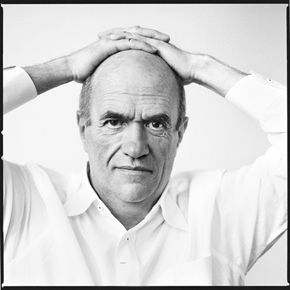

Colm Tóibín was born in Enniscorthy in 1955. He is the author of nine novels including The Master, Brooklyn, The Testament of Mary and Nora Webster. His work has been shortlisted for the Booker three times, and won the Costa Novel Award and the Impac Award. His most recent novel is House of Names. He has also published two collections of stories and many works of non-fiction. He lives in Dublin. Mad, Bad, Dangerous to Know is published by Viking/Penguin in hardback, eBook and audio download, read by the author.

Colm Tóibín was born in Enniscorthy in 1955. He is the author of nine novels including The Master, Brooklyn, The Testament of Mary and Nora Webster. His work has been shortlisted for the Booker three times, and won the Costa Novel Award and the Impac Award. His most recent novel is House of Names. He has also published two collections of stories and many works of non-fiction. He lives in Dublin. Mad, Bad, Dangerous to Know is published by Viking/Penguin in hardback, eBook and audio download, read by the author.

Read more

colmtoibin.com

Author portrait © Brigitte Lacombe

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.