Marbles

by Nicholas Royle

“A tribute to all in life that is witty, modest and caring. Touching, tender and moving.” Independent

I have lost plenty of people. Every loss is a lessening. Every loss makes one more aware of how much there is to lose. But the death of my mother was something else. I don’t know when she died. She had dementia. For ten years she was among us in the midst of life cut off. An island going down under rising sea-levels. A skyscraper collapsing in a decade-long earthquake. A sunset sleepier than a druid’s daydream. It began in her mid-sixties. It was over before her seventy-fifth birthday. It wasn’t like an island or a skyscraper or a sunset. These similes are to no purpose. Nothing captures the pace of her descent into where she went.

Like others near and dear I pretended it wasn’t happening. I’d ask if she would like a coffee. I’d suggest we go shopping or take a drive down to the sea. I’d say these things as if she was right as rain. I appeared to be unscathed. Not sinking an inch. I would see that she wasn’t answering but act as if the pause in the footage was someone else’s problem. A technical glitch. It could be ignored. It would come clear in a moment. I could see that she was not listening. She was looking out of the window at the birds around the bird-table. I would repeat the question. She would turn to me with whorls in her eyes. She would look in my direction as if. As if if. As if if I could just repeat the question one more time – just once more – it would connect. Repetition the mother of memory. As if if things could just rewind this era might start over. Here we are. Regained. We’d drive down to the coast. Walk arm in arm past the fishermen’s huts along the dark Jurassic shore. Drive over the fragile medieval bridge into the little town and sit in one of her favourite pubs. She would have her cup of coffee. I would have my pint of beer.

When does a mother die?

—

I’m losing my marbles.

So she said one autumn morning in Devon. It was in the kitchen. I had just taken a coffee bean out of the machine and was chewing it slowly.

Losing her marbles. In the past she might have said this of an old friend or elderly family member. My grandfather’s cousin or my mother’s great-aunt in Scotland whom we would not see for several years at a time. She and I would head north. Like a band on tour. A duo without audience. We would drive through the Great Glen. Listening to the jigging charm and melancholy of Mark Knopfler’s Local Hero or the road-to-nowhere Little Creatures album by Talking Heads. We would stop on Skye or Mull. Or we’d go up east – away past

Loch Ness and down again. We would stay in bed-and-breakfasts. Sharing a twin room. At some point on the tour (as arranged in advance by letter) we visited Cousin Nessie in her time-capsule of a cottage on the Square at Drymen. Cups and saucers clinked and teaspoons tinkled. The clock of ages on the mantelpiece stumped up the hour and the half- and the quarter-hours in strange accusation. What is the past? What is a family? It made our hearts knock together. After tea and scones we left and my mother remarked that Nessie was losing her marbles. She said it with all the peremptoriness of a High Court judge. The verdict was sound.

My mother’s every utterance was a play before the law of written or printed matter. As if her voice threw round each word a gentle mantle of quotation marks… a mind mid-clue.”

On other occasions the loss of marbles escaped me. I had to reconsider what had taken place. The gestures. The looks. Things said. With a friend of my father’s in Somerset it had not been clear. But my mother had picked it up. Visible as an item of litter in an otherwise spotless National Trust garden. She was Acute personified. A bloodhound for lunacy in others. She would note a detail. A failure to retain something just said. An absence of attention. A lower score on the conversation chart. I always imagined her judging what others said – assessing their ability in the arena of wit and recollection and story-telling fast as lightning.

And about my father’s friend my mother was right. Within months he went from absent-minded to pit-stop care home to pushing up the daisies.

There must have been a point at which we failed to go back to see Cousin Nessie. Solitary in her time-capsule at Hillview Cottage. Her name cropped up only later. She’d passed away. The British way is with ‘away’. Americans go without it. She’d passed. The away may be superfluous but the American idiom has a Christian tint: when people pass they pass to the Lord God or to heaven. And ‘away’ is such a dreamy two-in-one word. Fleet but longing. These details matter. The matter of my mater. Matador killing metaphor. My mother’s every utterance was a play before the law of written or printed matter. As if her voice threw round each word a gentle mantle of quotation marks. As if she spoke from a love for the provisional that understood that no locution was ever playful enough. A mind mid-clue. On occasion my mother would say that someone had died or passed away. But more often she would fling up some funny everyday idiom. Her father’s cousin in the Central Region was pushing up the daisies like the man in Somerset. She had popped her clogs.

Besides a fine nose for marble-loss my mother had a great taste for irony. ‘Irony’: I picture the word wrought and looped – gappy and splendid in the manner of the fencing in her beloved Richmond Park. Just another word for the invisible cloaks and lassos thrown. Many people failed to get her. A shopkeeper or dog-owner caught up in conversation could very soon be immobilised by her tongue. Impossible to ascertain the status of what this quick-witted woman had just said. They should all be strung up. Did she mean it? You look so much younger. Did she mean it? She could pull herself to pieces in a minute twenty times a day but did she ever mean any of it?

Still I don’t recall her ever saying in jest: I’m losing my marbles. For example at having mislaid the car key. Or forgetting an optician’s appointment. Which made the declaration that bright autumn morning with the intensity of the Colombian coffee bean disintegrating in my mouth all the more sickening.

My father and I had understood for months that something terrible was happening. You’ve been losing them for a good while (one of us might well have retorted). They’ve been rolling around scattering this way and that – slipping under the skirting-boards disappearing into previously unknown nooks and crannies whizzed off without a murmur every which way in a muted nightmare pinball – for a good while already. Nothing good about it. A terrible while. Hideous wile of a while. For you too must have known. And we had said nothing. Too choked to say. But now for the first time you were saying it yourself.

I played chess with madmen. I sang songs on request to old women. But I had never felt overtaken – submerged – rooted out by the reality of another’s madness.”

They were the saddest words ever spoken to me. I wanted it to be a duo’s refrain. I’m losing my marbles. A playful echo of other times. A riff of her old self making light of fetid fate. I wanted it to be immediately untrue. I wanted the judge to remove her wig and laugh the moment down the plughole. When my brother Simon and I shared a bedroom as boys and at night pleaded with her to come and frighten us by entering the room in different costumes – one minute a sheeted spectre – the next a fortune-teller – the next a shadowy crocodile – how we thrilled to be frightened. Knowing it was our mother in disguise. And now she was making a throwaway colloquialism scarier than a declaration of nuclear war. I was chilled to the marrow. Moribund metaphor. Icing on the cadaver cake. Cold clammy ivy wrapped my innards in an instant. And tears fell from my face incongruous as hot ice. I swallowed the fragments of the coffee bean. I prepared to vomit.

Nothing came. What to say? Rolling down my cheeks. My water marbles.

Ludicrous to pretend: No of course you’re not. Don’t be daft darling mother. Or to effuse: Yes yes of course. We had noticed. That’s why we’ve been trying to set up an appointment with the doctor. So that we can get you a proper diagnosis and see what medication might be prescribed.

My father and I were like hooded birds. Seeling our own fates.

Until then I’d never been shot through by dementia. In my late teens I had done some voluntary work at a local mental hospital. I spent afternoons in the company of the raving and sedated. Watched them watching the test card on the television screen from one hour to the next. Listened in fear to their anguished moans and cries. I played chess with madmen. I sang songs on request to old women. And in later years I visited friends who had undergone breakdowns and been sectioned. But I had never felt overtaken – submerged – rooted out by the reality of another’s madness. Mad judgment of the judge of madness. Trial of lunacy by lunacy. All the time headlong down a slide with no ground in sight.

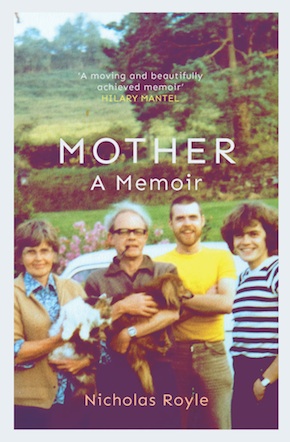

From Mother: A Memoir (Myriad Editions, £8.99)

Nicholas Royle is Professor of English at the University of Sussex, where he established the MA in Creative and Critical Writing in 2002. He is the author of the novels Quilt and An English Guide to Birdwatching and many other books, including studies of Elizabeth Bowen, Hélène Cixous, Jacques Derrida, E.M. Forster and Shakespeare. His books about literature and critical theory are widely influential and have won considerable acclaim. They include The Uncanny (2003), Veering: A Theory of Literature (2011), and An Introduction to Literature, Criticism and Theory (fifth edition, 2016, with Andrew Bennett). Mother: A Memoir is published by Myriad Editions in paperback and eBook.

Nicholas Royle is Professor of English at the University of Sussex, where he established the MA in Creative and Critical Writing in 2002. He is the author of the novels Quilt and An English Guide to Birdwatching and many other books, including studies of Elizabeth Bowen, Hélène Cixous, Jacques Derrida, E.M. Forster and Shakespeare. His books about literature and critical theory are widely influential and have won considerable acclaim. They include The Uncanny (2003), Veering: A Theory of Literature (2011), and An Introduction to Literature, Criticism and Theory (fifth edition, 2016, with Andrew Bennett). Mother: A Memoir is published by Myriad Editions in paperback and eBook.

Read more

@NicholasRoyle3

@MyriadEditions