The hydra of memory and forgetting

by Mika Provata-Carlone

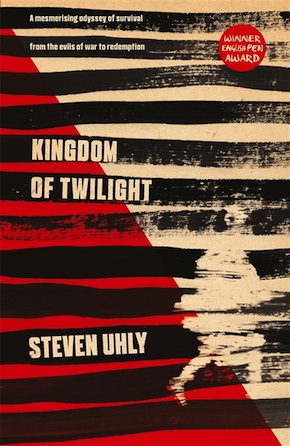

“One of the most important and powerful novels of recent German literature.” Deutschlandradio Kultur

“If you have no wounds, how can you know you are alive?” wrote Edward Albee in 1998’s The Play About the Baby. Steven Uhly’s Kingdom of Twilight could be said to be all about physical, psychological and historical wounds and about the true meaning of knowing oneself to be alive – the true worth of life itself. It begins with a typical Holocaust narrative: a Sturmbannführer (an SS major) is following a Pole who is to lead him to a hideout of Jews. In the brief span of that first chapter, among the familiar sinister threads of a Final Solution episode, is a succinct analysis of causes and beginnings; of the quintessentially monstrous theatricality and exhibitionism of Nazi ideology and social structures, of the unswayable determination to attain racial, national or individual supremacy: a perverse drive for greatness, for the power to wield an absolute will – and to impose it in its most extreme, most twisted and outrageously atrocious form.

The Sturmbannführer dies after a few pages, opening up the story to its many bifurcations and entangled human destinies. The woman who killed him will be hidden away by a couple of German settlers; she too will die and her baby will be raised by the German woman, whose husband will be forced to enlist and who will later die in Siberia. The Sturmbannführer’s commander will act true to character and retaliate for his subaltern’s death; he will have several Poles shot and he will rape his Jewish maid. He will then have her raped by his soldiers. It is a brutal beginning, a raw, unmitigated immersion into all that was, all the “horrors that human beings found hard to believe”, as Billy Wilder’s narrator comments in Mills of Death. Yet Kingdom of Twilight, fluidly translated by Jamie Bulloch, aspires to be more than staggering, unflinching Holocaust literature. It wishes to probe also into the before and after.

Juxtaposing monsters and bystanders, Uhly exposes the programmatic standardising of cruelty and slaughter. He also allows for the text of the interim period to be written, for stories that, compared to those of the millions who suffered Nazi ambition, action and ruthless effectiveness, can feel illegitimate, even perhaps sacrilegious. The historian Fred Taylor has called it the period between war and peace, the time of occupation by the Allies and the Soviets, the return of German prisoners from the Eastern Front and camps, the Morgenthau Plan and the Potsdam Agreement, and finally the Marshall Plan. In his uniquely lucid On the Natural History of Destruction, W.G. Sebald wrote that Germans resolved to make it especially a time of startling reinvention: “they make it look as if the image of total destruction was not the horrifying end of a collective aberration, but something more like the first stage of a brave new world”, and he quotes Robert Thomas Pell’s “amazement with which he heard Germans stating their intention of rebuilding their country to be ‘greater and stronger than ever before’ – in a tone in which self-pity, grovelling self-justification, a sense of injured innocence and defiance were curiously intermingled”.

Uhly asks questions that are as excruciatingly thorny as they are imperative and vital, questions long avoided under the weight of pain or for the sake of a fragile equilibrium.”

Kingdom of Twilight follows every human (and inhuman) path; of Jews escaping concentration camps or Germans fleeing the Soviet advance; of the new provisional camps for displaced persons, the new disinfestations, with DDT instead of Zyklon this time, the endless rootlessness and suspended identities. Of Nazis reborn as ordinary citizens leading casual family lives. Of Jews reclaiming a place in a Germany still hostile, still reluctant to grant them human status, national legitimacy, historical credit; or of Jews escaping to a Palestine they need to wrestle away from the British, secure against the Arabs, build, inhabit, define so that it can finally be their promised land. Without self-righteousness or falseness, Uhly succeeds in uttering the unsayable: the Nazis did not disappear after Germany lost the war. The denazification process was inspirationally conceived as a project of humanitarian grandeur and quickly abandoned: the logistics were impossible, the Soviet menace during the Cold War deemed more pressing than finished history. Forty-five million Germans were involved in one way or another (yet consciously in each case) in the central Nazi organisations, and Uhly asks us to look closely at how they were reintegrated, rehabilitated, absolved or ignored. He echoes, in that, Roosevelt’s and Thomas Mann’s position that it was not only a few Nazis who were responsible, but the German people as a whole. He also implies that the task of defining the kind of justice that will even the scales between victims and victors is vital but also critically difficult: gradually, methodically, retribution is ruled out, as is self-commiseration, self-destruction, or comfortable oblivion. Just as Jews had to reconcile with their faith in God after the Holocaust, Germans had to confront their own “filth chamber” of conscience, where they would place the past “before locking it and tossing away the key into oblivion”: history must be respected, safeguarded, studied and especially understood.

Kingdom of Twilight is a book full of complex metaphors – every Nazi is in denial, every Jewish character, or anti-Nazi German, suffers a split personality, survival guilt, pangs of doubt as to the very right to exist, or impulses of retribution. It is a particularly absorbing chronicle with deep humanity, tactility, the voices of many lives. Uhly asks questions that are as excruciatingly thorny as they are imperative and vital, questions long avoided under the weight of pain or for the sake of a fragile equilibrium “not based on sentiment or history but on common interest”, in the recent words of Lord Powell. Where did the vehemence, the hatred and the violence go in the aftermath of the war? What is the connection between the forced labourers of Nazi years and the Gastarbeiter that made the miracle of the New Germany possible? What were the attitudes of the British, the Americans, the French towards Jews after the war? What meaning does the abstract term ‘historical responsibility’ truly contain in comparison to collective guilt? What face did Germany give itself in the mirror of its conscience after it was all over?

This is a book about love, loneliness, despair, about a history of national hatred and horror, about the instinct of survival and the natural impulse for humanity.”

On a simpler, human level, when does trauma disappear? With some, Uhly suggests, it never does. It either becomes a misanthropic bitterness eternally shackling them to the cause of their suffering or a Vico-like spiral of inescapable circles of darkness, always recurring, ever widening. For some few, fortunate ones, trauma becomes a wisdom of kindness, a creative shrewdness, an awareness of the ‘what if’ that allows for a different course, and even, perhaps, for happiness. Kingdom of Twilight traces all these routes, as well as the paths of those who were scourges, tormentors, persecutors, ogres in human guise.

This is a book about love, loneliness, despair, about a history of national hatred and horror, about the instinct of survival and the natural impulse for humanity. It is a resolute questioning of evasion and escapism – for the innocent fleeing trauma, for the guilty shirking from the responsibility of culpability, from the confrontation with what was no less than sinning against the essence of existence. Uhly first scatters with calculated disorder the fragments of his many complementary tableaux. He then follows each through time, across unexpected, perfectly credible developments, by means of a beguiling richness of historical fact and human detail, to a present time of revelation, truth and assessment, shock, bereavement and atonement. Throughout Kingdom of Twilight, one hears almost uncannily the warning of Rabindranath Tagore against “the stilling of pain”, and for Germany, it was the generation of wartime children that undertook the task of seeking beginnings, confronting the terror, defeating the Hydra of a resisted memory.

Steven Uhly was born in 1964 in Cologne and is of German-Bengali descent, partially rooted in Spanish culture. He has studied literature, served as the head of an institute in Brazil, and translated poetry and prose from Spanish, Portuguese and English. He lives in Munich with his family. Kingdom of Twilight is published by MacLehose Press. Read more.

Steven Uhly was born in 1964 in Cologne and is of German-Bengali descent, partially rooted in Spanish culture. He has studied literature, served as the head of an institute in Brazil, and translated poetry and prose from Spanish, Portuguese and English. He lives in Munich with his family. Kingdom of Twilight is published by MacLehose Press. Read more.

Jamie Bulloch’s recent translations include Ruth Maier’s Diary: A Jewish Girl’s Life in Nazi Europe, Portrait of a Mother as a Young Woman by F.C. Delius, The Sweetness of Life by Paulus Hochgatter, Forever Yours by Daniel Glattauer and Look Who’s Back by Timur Vermes.

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.