Miriam Elia begs to differ

by Mark Reynolds

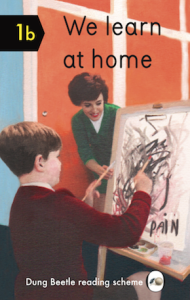

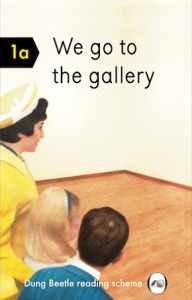

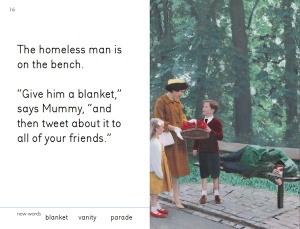

Artist and satirist Miriam Elia’s Ladybird-style spoof We go to the gallery was one of the self-made hits of 2015. It attracted both the ire and the opportunism of publishing giants Penguin, who own the copyright in the original, long-overlooked series, and tried to quash Miriam’s work while rushing out their own adult Ladybirds. Now, together with her brother and co-writer Ezra, Miriam has produced two more instalments in the Dung Beetle Learning series. In We learn at home, Mummy re-evaluates John and Susan’s core schooling subjects from a feelings-based outlook, while in We go out, the well-intentioned tyrant strips down every aspect of a simple walk on the high street to a struggle against patriarchal oppression. Just days before she gave birth to her new baby (welcome, Sidney), Miriam gave me some insights into her own background and worldview, and that skirmish with Penguin.

Artist and satirist Miriam Elia’s Ladybird-style spoof We go to the gallery was one of the self-made hits of 2015. It attracted both the ire and the opportunism of publishing giants Penguin, who own the copyright in the original, long-overlooked series, and tried to quash Miriam’s work while rushing out their own adult Ladybirds. Now, together with her brother and co-writer Ezra, Miriam has produced two more instalments in the Dung Beetle Learning series. In We learn at home, Mummy re-evaluates John and Susan’s core schooling subjects from a feelings-based outlook, while in We go out, the well-intentioned tyrant strips down every aspect of a simple walk on the high street to a struggle against patriarchal oppression. Just days before she gave birth to her new baby (welcome, Sidney), Miriam gave me some insights into her own background and worldview, and that skirmish with Penguin.

MR: Why did you choose art?

ME: It chose me. It’s like a religion, I didn’t have a choice. Both my parents are artists, so I grew up in a very visual family, and from an early age I was always making things. My dad’s an abstract artist. He earned money as a graphic designer, but he had his own studio where he did these weird, very minimal compositions. Squares, triangles, stuff he found in skips. Most of the time the whole house was stuffed with things he found in skips that he was reconfiguring in some abstract form, really funny and poetic little arrangements of things. My mum is more figurative – drawing and painting and direct observations. She had a sense of high camp, very theatrical. She worked with like Lindsay Kemp and the punk movement.

What’s the first piece of art you can remember making?

When I was about four or five, I remember walking through Wood Green High Street with my mum and seeing a woman who was probably heavily pregnant, and I said she looked like a bumpy staircase, and mum said, “Oh, draw that!” So I did. But she was quite old in the drawing, so maybe she wasn’t pregnant, she was just really fat. Mum kept all my drawings from childhood and a lot of them are quite funny. You’re not inhibited when you’re a kid, and she was always encouraging us to look at whatever was around us, which most people don’t do anymore. She was very much into observation, rather than looking at other artists’ work. She said that was bad, which was interesting.

So by the time you got to the RCA, what were you specialising in?

So by the time you got to the RCA, what were you specialising in?

I was in a bit of a mess, actually. I’d gone to art school at Brighton, I’d done years of graphic design and print making, which I really enjoyed, but I never wanted to be a graphic designer. I wasn’t sure why. I enjoyed learning about how to make things, like book binding, and I started hoarding a lot of Ladybird books and 1950s paraphernalia. I was only about 21 when they gave me a place at RCA, and everyone there was a lot older than me and had worked in the industry and got all jaded. It was like a refuge for them, but I was a bit frustrated. I had this thing about comedy for a long time, and when I finished at the RCA I’d just had enough of it all, the wine and cheese and private views, everything about it was starting to piss me off. So I did a stand-up comedy course, and then I managed to somehow get on the BBC with a show called ‘A Series of Psychotic Episodes’ and I was doing comedy for a long time, writing and performing comedy in bars and clubs, and I stopped doing visual work.

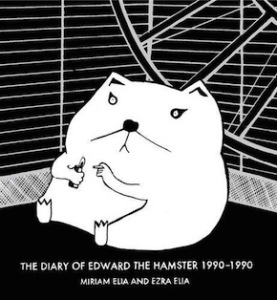

Your book Edward the Hamster, which you also wrote with Ezra, came out of that series. How involved was he in the radio show?

We were co-writers. I did the stand-up by myself, but I never felt as confident as him as a writer. He was always more wordy than I was. I had all these ideas and stories, but he could craft better. I thought about this hamster that we had growing up in Muswell Hill that was obviously depressive, living a very short lifespan, that was the only thing we’d been given as a pet. So I showed it to my mother – and this is a good lesson in life, don’t show things to your mother – and she said it’s not funny, she told me it was cruel to animals, so I put it in a folder on my desktop called ‘Bad Ideas’. Then Ezra and I were trying that night to come up with things, and he immediately latched onto it, and said, “Why did you throw this away, you idiot? It’s really funny!” So we started writing it as a monologue, and I started performing it in clubs. It got a really nice reaction, and I started writing a lot of jokes from the hamster’s perspective, and Ezra really kind of meated it out. It was hard because we were living off very little money, but we had complete creative freedom, which was amazing. And then I started drawing it, as these black-and-white, kind of Kafka-inspired images. The BBC had a small budget and said they could employ an animator to visualise the radio sketches, and they showed me these awful, badly drawn cartoons, so I said no, I’ll do it myself. And that was a pivotal, because I started drawing again. I’d stopped completely up till then.

One day I was sorting through my room and I said to Ezra, ‘Imagine these characters from these 1960s books looking at all this annoying stuff, trying to make sense of it.’ I got completely obsessed with it.”

And when did Pan Macmillan come calling?

And when did Pan Macmillan come calling?

Well it went online with Radio 4 as this animation, and I can’t remember the exact order of events, but they approached me saying do you want to make a book of your drawings and his diary? I didn’t know anything about publishing at that point, or how to make anything out of it. But it’s all a learning curve, isn’t it? But through that I did realise that I had the skills to draw, write and design a whole product without having to ask for anyone’s help.

What was the spark for We go to the gallery?

I was in comedy and I’d met an artist and I had a very rocky year or two after that relationship ended. It was a difficult time, and I made this work called ‘I fell in love with a conceptual artist… and it was totally meaningless’, which was my way of processing that whole thing. But it wasn’t really about the relationship, it was about coming to terms with being an artist and not fitting into the comedy world anymore. At that time I’d written like a I-Spy guide to everything I’d seen in art school, all the broken dolls and crucifixes and empty rooms, all the conceptual clichés and the double-speak – the lack of observation, actually. Whereas my mother when I was a child was always saying, “Look, look, look, look, look,” they were saying, “Don’t look, don’t look. Come here into this little cocoon away from the world,” but I wanted to engage with it.

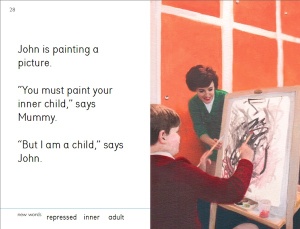

Then one day I was sorting through my room, which was a complete tip, full of Ladybird books and old things I’d hoarded from Brighton, and I said to Ezra, “Imagine these characters from these 1960s books looking at all this annoying stuff, trying to make sense of it,” and I started on that, and I got completely obsessed with it. I started by making collages and then paintings in that style. The first one was ‘God is dead’, the empty room, that really made me laugh, then I had the ‘Why did you fuck me and leave?’ from the conceptual artist work, you just find bits from all over, and then the idea became this journey through a gallery. I illustrated everything, and then we wrote it, which is an interesting way of working. So it was visual first, and then the idea was how does the mother explain this to the children in a language for under-5s? That was the challenge: it had to get simpler and simpler.

And once you decided to actually make a book, what were your expectations?

I was just extremely excited. I had no money, I was about a grand overdrawn, and living at my parents’ house but I didn’t care. I had a little studio in Southgate Road in Islington with some textile people, they let me have a little desk there, and the Cob Gallery gave me a desk as well, just so I could get out of the house. I was completely in love with it, and every time I showed it to anyone they started laughing, so I was like, “Ha, ha ha, it works!”

And then Penguin got wind of it…

And then Penguin got wind of it…

I swear hand on heart I had no idea that they would even be concerned by it. Maybe I was really naïve, but it was just an art project, just “I have to do this, I have to finish it, and it has to look like this, and the spine has to be a certain way.” I studied how the original Ladybird books were made, there was a lot of obsessing over it. The initial run was 1,000 and they were launched in the Cob Gallery in Camden Town, and then the Independent wanted to interview me and they asked me, “Have you asked Ladybird’s permission to make this book?” and I said, “It’s an art work, no. Why would I ask anyone permission to make an art work?” And they printed that, and I was lying in bed that night thinking maybe I shouldn’t have said that… and that’s when it all kicked off.

It just seemed so weird, why would they be upset about it? Everyone was saying how funny it was, it was just a vehicle for exercising something I wanted to say, I wasn’t having a go at them, there was nothing about it that’s saying look how stupid they are. I just couldn’t get my head round why they were so upset. At that time it started picking up online and people were sharing it.

I had to get a solicitor because they were sending me these threatening letters saying I had to send them all my art for destruction. If something takes you that long to make you’re not going to give it up, so I just refused, and they got more and more obsessed with it and I just refused more and more to do anything they said. It was quite funny, but it cost me a lot of money and time and it was very stressful.

Reinventing it as a Dung Beetle book was a gamble, but I just thought, they don’t want to let me do anything but I will, I’ll find a way through it. So I printed another very small run of the Dung Beetle books to test what would happen.

How did it feel to see We go to the gallery displayed in bookshops alongside Penguin’s own spoof Ladybirds?

Now, I didn’t know that would happen. I’d just printed the first batch of 20,000, which was a huge run for me, and I got a bit of support from the London Small Business Centre, they helped me raise the initial print cost, but I was still really scared. We went to Vietnam on holiday, and then while we were there Ezra called me to say, “Have you heard the news?” Penguin had gone quiet for about three or four months, maybe even longer, and we got back from Vietnam and suddenly there were like eight ‘satirical’ new Ladybirds and I was quite upset. It was shocking, actually. I basically opened up a whole market for them, because no way would they have done that otherwise. I’m not the first person to reference a Ladybird book, I’m aware of that, but as far as I know I’m the first person to make a complete work of satire and publish it, and create an actual, physical object with paintings and original text. That hadn’t been done. But all these people have done is just taken old images and written a bit of new text. It’s easy, you could do that in ten minutes. The covers were clever but there’s no substance. I mean, if you’re going to do anything, at least write a good joke!

So will there be more Dung Beetles? Do you know what subjects you might tackle next?

So will there be more Dung Beetles? Do you know what subjects you might tackle next?

I’m not quite sure yet, because I’m about to have a child. But I think it will be really interesting becoming a mother myself, and I’m really gathering a lot of material on the whole baby industry that I’m now experiencing hands-on.

What kind of Mummy do you expect to become?

No idea! Just be myself. I’ve been very anxious about that. What kind of parenting technique? I don’t know, just don’t spoil them.

And have you ruled out home schooling?

I thought that was really funny as a device, for the mother in the book to recondition her children with progressive education. I really enjoyed making that. But I don’t know yet, I haven’t ruled out anything.

Schooldays can teach you a lot about hierarchies and boundaries – and when to disobey.

It’s funny because I was taught polar opposite things at every school I went to. On the one hand I went to a very religious school, and then I went to Acland Burghley which was a secular kind of artistic experiment in north London, and then I had a secular primary school, and then I went to a really right-wing comprehensive. So I was always taking in lots of different value systems, I thought they were all quite hilarious.

Did you conform at any of them?

No, never. Wherever you put me, I just react against it: “You’re all idiots!” That’s a problem, isn’t it? Actually I was thinking about that, I’ve never really been happy anywhere, I’ve never really agreed with anyone!

Miriam Elia is an artist, writer and satirist. Much of her text-based work is produced in collaboration with her brother Ezra. Their first book, The Diary of Edward the Hamster: 1990–1990, was published by Pan Macmillan in 2012. She founded Dung Beetle Books in 2015. Her art work comprises collage, illustration, print making, short films and live performance and has been covered in publications including the Independent, The Times, the Guardian and Dazed & Confused. Artists’ editions of We learn at home and We go out were published in August 2016, and commercial editions are now available in all good bookshops. Read more.

Miriam Elia is an artist, writer and satirist. Much of her text-based work is produced in collaboration with her brother Ezra. Their first book, The Diary of Edward the Hamster: 1990–1990, was published by Pan Macmillan in 2012. She founded Dung Beetle Books in 2015. Her art work comprises collage, illustration, print making, short films and live performance and has been covered in publications including the Independent, The Times, the Guardian and Dazed & Confused. Artists’ editions of We learn at home and We go out were published in August 2016, and commercial editions are now available in all good bookshops. Read more.

miriamelia.co.uk

@Miriamelia1

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.