Ned Beauman: Intelligent life

by Mark Reynolds

“Funny and profound, full of extraordinary ideas and brilliant set pieces, but also generous and poignant… a novel that delights, dazzles and moves in equal measure.” Alex Preston, FT

Ned Beauman’s Venomous Lumpsucker is a dazzling satire of a near-future Europe in which global warming-led species decline has become accepted as an unfortunate by-product of economic growth. A system of ‘extinction credits’ means that any company set to gain financially from operations that happen to wipe out an endangered species simply has to purchase a permit to carry on regardless – which only serves to accelerate the rate of extinctions. This in turn has given rise to a radical new definition of extinction, whereby if the species has been eradicated in the wild, but a full biobank record of its DNA, physical attributes, habitats and behaviours exists on file on a supercomputer biobank, it can be considered to still virtually exist.

The world order is skewed from its current axis: Britain is isolated and economically adrift from the rest of Europe (due no doubt to a run of persistently disastrous government policies based around dubious ideals of freedom and autonomy), and the USA has done something literally unspeakable that has turned it into an international pariah.

Against this backdrop, animal-intelligence scientist Karin Resaint and crooked mining exec Mark Halyard have differing reasons to be alarmed at the reported extinction of the Venomous Lumpsucker, a fish of unusual intelligence and exceptional human-like behaviours (communal living, social hierarchy, murderous revenge…). As Resaint and Halyard team up to scour the natural world to investigate whether any specimens remain in the wild, they come up against sinister market forces and conspiracies that threaten to block their path.

Mark: To be clear from the start, a Venomous Lumpsucker isn’t a species currently known to science. How many other species, living or imagined, did you consider before turning to this unsightly but highly intelligent and socially developed fish?

Ned: I knew it had to be a fictional species so I would have the freedom to make up all the details (also, a real one might have gone extinct while I was writing the book). It definitely couldn’t be a mammal because the pool of European mammals is so small (less than three hundred) that it just wouldn’t be plausible for there to be a fairly intelligent one that nobody’s ever heard of. And it couldn’t be a bird, reptile or amphibian either, because in the course of the plot there has to be some uncertainty about whether this species is extinct, and if you’re a naturalist in the 2030s and you want to know whether a non-aquatic species is still hanging around somewhere you can probably just send a few drones to have a look. Whereas the ocean is a murky place full of obscure creatures. So I invented a fish.

As Karin acknowledges: “If you really can’t see intelligence in the ability of a shrub to recover from having ninety-five per cent of its mass consumed by goats, maybe you’re the vegetable.” What is the best definition you have encountered of ‘intelligent life’?

I want to note first of all that this line is a borrowing from Justin E.H. Smith’s essay ‘The Problem with “Animal Intelligence”’, which Resaint has probably read. Justin goes on to say, “The more we reflect on the matter, the more ‘intelligence’ comes to appear not so much as the name of a general faculty we may observe and measure in our own and other species, as rather an honorific term that we extend to beings and systems manifesting behaviour that reminds us of ourselves. We use tools, we count, and we recognise ourselves in the mirror, and so we take an interest in the ability of certain other species to do the same.” Here he is in agreement with Denise L. Herzing, a pioneering dolphin scientist who I mention in the book. Herzing has a paper called ‘Profiling nonhuman intelligence: An exercise in developing unbiased tools for describing other “types” of intelligence on earth’, which argues we need metrics that aren’t overly anthropocentric, so that they’ll have the flexibility to recognise ‘weirder’ forms of intelligence. She suggests these might be helpful if we ever encounter alien life!

When I had the idea for extinction credits I thought it was wildly satirical, but then I discovered that in fact the US, Canada and Australia all have forms of ‘biodiversity banking’.”

You paint a pretty bleak picture of our capacity to ward off global warming and species extinction. Are you as pessimistic as these projections appear to suggest? And do you think something like extinction credits could become a reality?

The future I imagine in the book is one in which nothing particularly major has been done to avert the climate crisis, and yes that’s how I see things playing out. As I understand it, things aren’t looking quite as gloomy as they were a few years ago, but all the same a Second World War-type global mobilisation, which is what we need, is clearly not on the cards. And I certainly think extinction credits could become a reality because it already is a reality! Well, not quite, but almost. When I had the idea for extinction credits I thought it was wildly satirical, but then I discovered that in fact the US, Canada and Australia all have forms of ‘biodiversity banking’, where a developer who wants to flatten some wetlands is obliged to pay somebody else to not flatten their wetlands. It’s an attempt to treat ecosystems, the most complex things in the world, as if they were as abstract and fungible as money – and of course you’re relying on some underfunded government agency to keep track of whether it’s working remotely as intended. Extinction credits is just an exaggerated version of that.

You depict artificial intelligence advanced way beyond human understanding, and set to eventually outlive our species. What do you suppose the planet would be like if AI algorithms were left to make all the decisions about the future of biological life on the planet?

Well, one of the points I make in the book is that an AI algorithm is already making most of the decisions about the future of biological life on the planet – that algorithm is free-market capitalism. However, if we’re talking about a computer mind, then obviously it would depend on what goals we gave it when we designed it. If we simply told it to safeguard biodiversity above all else, I imagine it would immediately eradicate the majority of living human beings and ensure that our population never again rose above nine figures. Whereas, if we allowed the AI to invent its own goals, there’s no reason to think it would care about biological life at all. However, if it did, I suppose it might observe that the lives of most animals in the wild are blighted by hunger, fear, disease and violence, and decide that nature ought to be radically reshaped, even at the cost of some biodiversity, to make sure that everyone could have a nicer time.

Presumably you were working on your final edits during lockdown. Did living through a pandemic affect the atmosphere you set out to evoke?

The pandemic was inconvenient for Venomous Lumpsucker mostly because in the early months a lot of people were saying that international travel was over forever and the two main characters of my book are supposed to fly all over the place for their jobs. Obviously I couldn’t rewrite it so everything happens over Zoom! I did jam in a line about needing to show a vaccine passport on your phone before you could go into a hotel lobby, which seemed plausible at the time, but no longer does (unless we get another, worse pandemic in a few years – which according to the book we do). Conversely, a lot of people were saying we were going to be plunged into a deep and prolonged recession, and that was actually helpful for my world-building – but then there was an almost immediate recovery, so I had to hastily remove a couple of details about the recession – and now it looks like we are getting a recession after all, but partly for reasons nobody anticipated. Which illustrates the difficulty of trying to write something set in the near future.

You conjure up future technologies of the kind that Greta Thunberg has warned against us trusting in to solve the climate crisis. Do you expect that genetically modified peat moss capable of digesting poisonous pollutants will remain a pipe dream? And what is the closest science has so far achieved in the attempt to clean up human detritus?

I am actually pretty bullish on technology. For instance, the detail you mention was inspired by a real experiment where Norwegian researchers used peat moss to help clean up an oil spill after a tanker ran aground. And I’m sure in a couple of decades we’ll be doing amazing things with genetically engineered microbes. But ever since I got a dog I’ve become a complete fascist about street litter, so frankly the invention I’m most excited about is litter-picking robots.

The environmental fraud laws you describe are punitive, at least on paper: “Give a lot of kids severe asthma, and you couldn’t expect to be treated any better than the sicko who’d choked a few with his bare hands, just because you’d taken a more roundabout route to the same result.”Unfortunately those laws don’t quite exist yet, and even in your future world they’re pretty easy to evade…

I do believe, as is predicted in the book, that as the effects of climate change become more painful there will be a greater public demand for retributive justice. In Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Ministry for the Future, it’s a mega-heatwave in India that finally puts the fossil fuel executives in the firing line. But, famously, nobody in the US went to prison for the financial crisis. So will the same apply here? Personally I’m in favour of Nuremberg trials for the guys who knowingly suppressed the scientific evidence for the sake of their profits, but I don’t actually think I will live to see that happen. One of the things that corporations are very good for is anonymous, diffuse responsibility. Look at the water companies illegally dumping sewage into our rivers. The individuals who made the decision to do that have much less to fear than, say, a pop star who says something crass in an interview. Despite having such advanced machinery for ostracism at our disposal, we can’t even get it together to torch their names on social media, much less force them out of their jobs, much less actually punish them.

One of the things that corporations are very good for is anonymous, diffuse responsibility. Look at the water companies illegally dumping sewage into our rivers.”

There are also dire warnings about trusting in automated facial recognition as the basis of justice and security systems. Are you concerned that we’re heading blindly down that path?

Actually I’m not sure the problem is that we will trust facial recognition too much. I would much rather have a computer decide whether I committed a crime than a human being at a police station, because the computer is more likely to be right. Within a few more years I imagine facial recognition will be virtually infallible. What’s scarier is the uses it will be put to in the future. I don’t mean governments identifying protestors – that’s not the future, that’s already here – I mean any old creep having it in his pocket. Even today, if you have the right industry contacts, you can get an app like Clearview that allows you to identify anybody you see on a train, in a bar etc. in real time. I think when we all have that on our phones it’s going to make daily life extremely weird, especially for women.

The dark humour in the book put me in mind at various points of A Hitchhikers’ Guide to the Galaxy, Dr Strangelove and Slaughterhouse-Five. What are your touchstones for comic speculative fiction?

Yes, I used to love Douglas Adams when I was younger (which is not to say I’ve grown out of him, I’m sure I would still love it now). Also as a teenager I reread Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash more times than I can count, plus I hesitate to mention this given the allegations against him but I’d be lying if I said Warren Ellis’ Transmetropolitan wasn’t a seminal series for me back then. Philip K. Dick can be pretty funny at times, and one has to add Gary Shteyngart’s Super Sad True Love Story.

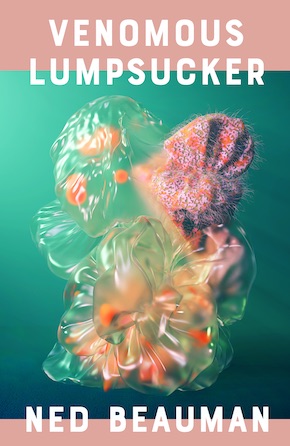

The image on the cover kept me guessing until the final chapters. Did you drive that choice, or was it the folks at Sceptre? I see that the US publisher Soho Press opted for a recognisable lumpsucker…

When we were working out what to do with the cover I came across a Danish CGI artist called Caroline Vang on Instagram and I thought she’d be perfect. The image isn’t supposed to represent anything specific from the book – it was an already-existing piece that we bought from her – but to me it simultaneously evokes sea life, biotech experiments, and a slightly disconcerting futurity, which is everything we wanted. Thanks to Sceptre I’ve now had a run of five great covers in a row, so when you buy one of my books you know you’re getting totally adequate content in a totally beautiful wrapper – that’s the Ned Beauman Promise.

Why is it essential to poke fun at our shortcomings in mitigating global warming and species collapse?

I wrote a comic novel about this for the same reason I wrote a comic novel about the rise of the Nazis – I’m really interested in what it’s like to live at a time of unspeakable tragedy, but I just don’t have the essential moral seriousness that you need to write an earnest, moving novel about these things, so I go for black comedy instead. Also, wildlife conservation is inherently pretty funny at times. After the Exxon Valdez spill in 1989, they rescued about three hundred otters so they could clean the oil off them and release them back into the wild, but the process was so painstaking, and so many of them died in captivity, that it ended up costing about $80,000 per surviving otter. I can’t help but laugh at the absurdity of that, even though I feel sorry for the otters.

Which books have you read lately that you particularly admire and recommend?

The two most enjoyable books I’ve read in the past twelve months are David Niven’s The Moon’s a Balloon and Norman Rush’s Mating. In fact, paragraph for paragraph, The Moon’s a Balloon might be the single most delightful book I’ve ever read, especially in the first half before his career takes off – and it doesn’t matter if you barely know who David Niven is. Meanwhile, I had put off reading Mating despite many trustworthy recommendations because it’s a 500-page novel about a romantic relationship, which is not remotely my thing, but I soon realised that in fact it’s a supreme example of one of my favourite genres, namely a very intelligent person explaining a series of complicated things to you in lucid and good-humoured prose.

Archery Pictures have optioned the TV rights to Venomous Lumpsucker. What is their vision for the series, and what are the main challenges they will face in bringing it to the screen?

I haven’t talked to them about this at all, but for me the main challenge is that the story is 1. set in a Westworld-type future with flying cars and floating cities, which means big budget, but also 2. about a fairly unsexy subject, which means niche audience – and those two things are not compatible in the TV industry. My guess is the first thing they’ll do is take out the flying cars.

Which of your other books are currently in development for TV or film?

Boxer, Beetle, The Teleportation Accident, Glow and a couple of my short stories have all been in development at one time or another but as far as I know nothing is happening with any of them anymore. Which is normal. I noticed that after the announcement about Venomous Lumpsucker a few people seemed to take ‘the book has been optioned’ as equivalent to ‘it’s going to be a TV series’ – but it does not mean that at all! I do have a few original projects of my own in development as well but I wouldn’t exactly bet my life on those either.

What are you writing next?

You’d think I would have learned my lesson about current events rendering my work obsolete, but actually my next novel is about the present-day UK political situation, which means it will almost definitely be irrelevant by the time I finish answering this question, let alone by the time I finish writing it, let alone by the time it’s actually published.

Ned Beauman is the author of Boxer, Beetle, winner of the Writers’ Guild Award for Best Fiction Book and the Goldberg Prize for Outstanding Debut Fiction; The Teleportation Accident, which was longlisted for the Man Booker Prize and won the Encore Award and a Somerset Maugham Award; and the highly acclaimed Glow and Madness is Better Than Defeat. He lives in London. Venomous Lumpsucker is published by Sceptre in hardback, eBook and audio download.

Ned Beauman is the author of Boxer, Beetle, winner of the Writers’ Guild Award for Best Fiction Book and the Goldberg Prize for Outstanding Debut Fiction; The Teleportation Accident, which was longlisted for the Man Booker Prize and won the Encore Award and a Somerset Maugham Award; and the highly acclaimed Glow and Madness is Better Than Defeat. He lives in London. Venomous Lumpsucker is published by Sceptre in hardback, eBook and audio download.

Read more

nedbeauman.co.uk

nedbeauman.blogspot.com

@NedBeauman

@SceptreBooks

Author portrait © Alice Neale

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.

@bookanista

wearebookanista

bookanista.com/author/mark