Nikesh Shukla: Superhumour

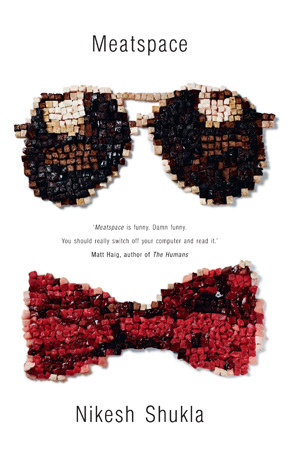

by Emma YoungMeatspace is the second novel from Costa First Novel Award shortlisted author Nikesh Shukla. It follows Kitab Balasubramanyam (‘Kit’ for short) as he deals with heartbreak, unemployment and an online namesake-turned-stalker. When Aziz, Kit’s brother and flatmate, leaves him to track down his doppelgänger in America, Kit finds it harder and harder to maintain his grip on reality and resist the temptation to tweet everything he does, or wishes he’d done. Gary Shteyngart called it “the greatest book on loneliness since The Catcher in the Rye”.

EY: First off, can you talk a little bit about the title which I, ahem, might have had to google, and your interest in the relationship between the real and virtual worlds we inhabit?

NS: I love the idea that our online interactions have replaced our physical ones as genuine ways of cultivating friendships, relationships and working partnerships, and this means that we view the real world as meat, a fleshy place. I dunno, there’s something fascinating about how we’ve made the very idea of occupying the same space together sound and feel disgusting, like we’re chicken wings or rump steaks all vying for space. The book started in three places – the first was being asked to write a short story about social media for BBC Radio 4 (naaamedrop). I wrote something about deleting my mum’s Facebook account when she died and how that digital footprint seemed more indelible than her soul, which saddened me. Because her Facebook account was a collection of photos and likes and dislikes and not the essence of a person. The second was, when joking with my mate Rob about getting a tattoo to make him look smarter (he has full-sleeve tattoos), we googled bow-tie tattoos. The first person in Google image search was a scary doppelganger for Rob. Really really scarily Rob-a-like. Within seconds, we’d found his website, Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn, and suddenly I knew all these things about him (not who he was) and was surprised by how easy all that was to find. The third inciting incident for writing the book was in 2010, when the second Nikesh Shukla in the world signed up for a Facebook account and suddenly I was not a social media Googlewhack anymore. It made me sad. I sent him a questionnaire to see how alike we were. He never replied.

The novel is – at least in part – a warning against falling too far from meatspace, and yet you’re a big Twitterer and general online bod. Are you exploring your own deepest fears?

Yeah, Meatspace is definitely where I could have ended up had I embraced the darkness around me and around that particular corner of the internet where you can say and do anything without any real consequence. I remember when my mum passed away in 2010 and I was promoting Coconut Unlimited, I spent a lot of time walking around the city listening to Ghostpoet, on my way home from readings, just embracing the quiet weirdness of a city in the witching hour. At the time, Twitter was the only thing awake. I had to restrain myself from using it as therapy. I could have very easily become one of those people who said and thought everything in a public sphere, and I thought, for me that would have been dark. So yeah, Meatspace is where that darkness was channelled. What would my life look like if everything I said and did went online and that was how I measured my self-worth, what kind of interactions I got back. Now, I think the most important part of using social media for me is maintaining the separation between who I am in person and who I am online.

I loved the section of the novel set in New York City, which read like a comic to me, and I know you’re a comics fan. What comics inspired you, and did you see these influences seeping into the other threads of the narrative?

I’m a huge Spider-Man fan. A huge one. I like to imagine the blog sections of the book are Spider-Man comics narrated by a teenager doing a vlog. It was important to try and conjure this hyper-real world where you as the reader question where the line is between what’s really happening and how you replicate it online, and what that means for truth. I firmly believe that whatever truth we represent online is a curated one, that we’ve workshopped in our heads, one that presents the perfect version of truth. With the comic feel, I love the way Stan Lee wrote. He wrote superheroes like no one else. The thing with DC is, it’s very weighty and serious and everyone has problems and everything hurts and it’s all epic and dark and complex and… joyless. The Marvel universe that Stan Lee wrote was full of hepcat jazz dialogue, zingers and brilliantly energetic prose, dialogue and stage directions that constantly broke the third wall and questioned the nature of storytelling while Kapowing Blamming and Thwiping across the rooftops of New York.

I found your depictions of family relationships heartbreaking – Kit’s relationship with his brother, and his father who can’t seem to strike the balance between playing dad and awkward friend. How did you go about researching and writing these characters?

How to skirt around the fact that I looked at my own relationship with my dad… I jest. The book’s about responsibility, right? Taking responsibility for how you like your life, how much you give to the internet, how much you give to life. The male relationships – how they’ve all failed each other, Kit and his brother and his father – are very much about not taking responsibility for how you should take care of your people when they’re in crises. It’s a very male problem to arse about and make jokes instead of dealing with a problem. That’s how Kit and Aziz deal with things; instead of being a father to his children, Kit’s dad is about being selfish, taking things back for himself and trying to not be tied to any responsibility, and that means he neglects what role he should be playing in Kit’s life, especially in this crisis of his. And this impacts how Kit views the brotherly, fatherly, mentorly relationship ‘Kitab 2’ insists he must have in his life. I take these things from the relationships and the dynamics around me and how I relate to my family and to my friends. I think people who know me will read the book and try and make links to my own life, but that’s the trick about writing comedy – you write what you know and you amp up the pain and the tragedy and the singular weirdness of people, and then you’ve got something people can laugh at. By taking elements of my real life and making it grotesque.

You also write terribly affectingly about break-ups, and I laughed out loud at many points during the novel, most uncontrollably when Kit makes a replacement girlfriend out of his bedding and announces: “I call her Quiltina”, and when Kit meets Kit 2, and remarks: “I was immediately disappointed that my namesake was so Indian-looking.” Can you talk a little about how you use humour?

Like I said before, I take elements of things around me and turn up the pain and tragedy and grotesqueness until it’s funny, to me anyway. It’s important that the laughs are relatable and warm. I hate cold humour when we’re all implicitly in the mauling of a thing for comedic effect. That makes me feel uncomfortable. I like the laughs that bring something out in us that resonates in our lives. I love shows like Arrested Development because, much as this family dynamic is so utterly gross and disgusting, they contain a universal truth, a relatable way of acting and interacting that resonates with our own lives. Also, the writers love their characters so much and because they do, they’re able to really take them to the extremes and make them do unspeakable things, and these will be dealt with warmly. I like to think I do the same. I’m as influenced by sitcom and comedy as I am books.

The entire novel feels original and fresh even though many of the subjects it discusses aren’t issues unfamiliar to the reader. The way you write dialogue is vital to this, I think, and feels very authentic. How do you go about creating it? I want to picture you yelling about porn in the British Library, essentially.

So there was this time I got banned from the British Library for trying to access RedTube in the toilets on my phone… No, definitely, dialogue is really important. And this is where my sitcom obsession comes in. Too much dialogue in books reads like dialogue in books, where it’s either advancing plot or it feels utterly contrived and not like any words that anyone would say ever. I spend a lot of time reading stuff back to myself out aloud. Kevin Barry told me (naaamedrop) he does this too, but he has a two-level desk, where he can write the bulk of the text, then stand up and read things back to himself aloud and work on it while pacing. I don’t have the money or the walls for a two-level desk, but I do spend a lot of time honing the dialogue till it feels real, till it feels of its character and till it feels like it’s been written with a lexicon and a rhythm and syntax that sounds like a guy might say it.

Speaking of porn and the British Library, how fun was it to recreate the London publishing scene in your writing, and what do you think of other novelists’ attempts to do this?

Mine was a very low-level London publishing scene – it was set at a reading that wasn’t too far from something like Book Slam and with writers who are suffering from that writers-now problem where they have to balance writing with actually making money. It’s not like the six-figure advances of yore. It’s a now where we write marketing copy and work in coffee shops and spunk our parents’ inheritances all in the name of suffering for our art. But it’s a London publishing scene that’s real to me. It’s not like when I read Howard Jacobson or Edward St Aubyn – I mean, I’m sure how they write it exists, but it’s nowhere near a reality I’m familiar or comfortable with, so this was a book for all the writers out there who do the readings, stay late and go to work in their quantity surveyor day jobs with hangovers, and write their novels on Google Drive when no one’s watching.

And finally, what are you reading at the moment, and what’s coming out in the next few months that you’re looking forward to?

I just finished Simon Rich’s next short story collection, Spoiled Brats, which is really excellently funny, as his stuff usually is. The centrepiece, a novella called Sell-Out is ridiculously chortlesome. Also, I just read Bilal Tanweer’s stunning short story collection The Scatter Here Is Too Great. I’m really looking forward to Niven Govinden’s All of the Days and All of the Nights, Salena Godden’s Springfield Road and Chimene Suleyman’s Outside Looking On, because they’re both incredible writers and I love everything they do. I also recently finished reading The Way Inn by Will Wiles, which is weird and creepy and funny.

Nikesh Shukla’s debut novel Coconut Unlimited (2010) was shortlisted for the Costa First Novel Award and longlisted for the Desmond Elliott Prize. In 2011, he co-wrote a non-fiction essay about the riots with Kieran Yates called ‘Generation Vexed: What the Riots Don’t Tell Us About Our Nation’s Youth’. In 2013, he released a novella about food called The Time Machine, donating all his proceeds to the Roy Castle Lung Cancer Foundation. His short stories have featured in Best British Short Stories 2013, Five Dials, The Moth, The Sunday Times and on Radio 4, among others, and he has written for the Guardian, Esquire and BBC 2. He hosts The Subaltern Podcast, the anti-panel discussion featuring conversations with writers about writing. Meatspace is published by The Friday Project. Read more.

Nikesh Shukla’s debut novel Coconut Unlimited (2010) was shortlisted for the Costa First Novel Award and longlisted for the Desmond Elliott Prize. In 2011, he co-wrote a non-fiction essay about the riots with Kieran Yates called ‘Generation Vexed: What the Riots Don’t Tell Us About Our Nation’s Youth’. In 2013, he released a novella about food called The Time Machine, donating all his proceeds to the Roy Castle Lung Cancer Foundation. His short stories have featured in Best British Short Stories 2013, Five Dials, The Moth, The Sunday Times and on Radio 4, among others, and he has written for the Guardian, Esquire and BBC 2. He hosts The Subaltern Podcast, the anti-panel discussion featuring conversations with writers about writing. Meatspace is published by The Friday Project. Read more.

nikesh-shukla.com

Emma Young, a former arts publicist and literary night host, is a contributing editor and events manager at Bookanista. Follow her on twitter: @emmaryoung