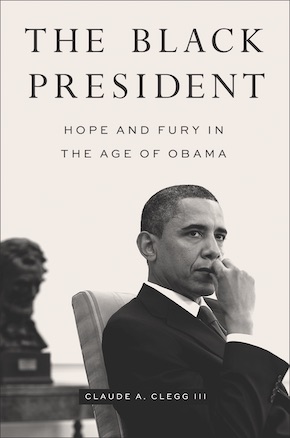

Obama the chameleon

by Claude A. Clegg III

“A gracefully written, scrupulously balanced and quite satisfying account of what Obama meant for Black Americans.” New York Times Book Review

The concept of race has no evidentiary basis in science or the serious study of the natural world, but as a social construction, it has had a powerful impact on the shaping of the modern era. Race has structured hierarchies and relationships within vast empires and between powerful nation-states and subjugated colonies for centuries. Further, the idea of race diminishes the significance of the individual and the many environmental variables that shape people and societies in favor of exaggerating the assumed existence of collective tendencies and differences between groups. Easily lending itself to racism and other extreme forms of racialized thinking, race is often employed to do its most vigorous labor in the service of justifying existing inequalities and can, in turn, set the stage for rationalizing future privilege and exploitation. As an ideological and a historical phenomenon that has shaped policy, practice and tradition, race, as experienced in any given setting, also has borders and protocols, which may exhibit varying degrees of porousness depending on conditions. For the individual not easily characterized visually or culturally within conventional racial categories, the navigating of race can be deployed for advantage, allowing for inconspicuous movement across boundaries and even long-term, if precarious, residence in the gray areas between socially acknowledged racial identities.

In this vein, Barack Obama is an intriguing and instructive case study – both in his observed, lived experiences and as a practitioner of narrative self-making – of the nexus of several racial, ethnic and cultural identities, each of which shaped and helped project his sense of self and being. Many of his early – and more frank and less politically filtered – ruminations on race are presented in his first book, Dreams from My Father. At once a memoir, travelogue and deeply introspective meditation, the volume is a poignant, probing chronicle of his efforts to reconcile himself with his eclectic lineage – embodied in his mixed racial heritage, his geographically dispersed kin and homelands, and his contentious paternal issues – and to discover his place and purpose in the world. In vivid, lively prose, he escorts readers through his childhood in Hawaii and Jakarta, between his undergraduate years at Occidental College and Columbia University, deep into a transformative stint as a community organizer on the South Side of Chicago, and alongside his Kenyan search for familial origins and affirmation. At its thematic core, the book is as much about coming of age as a Black youth in late twentieth-century America as it is about how Obama grappled with the more exotic circumstances of his birth and far-reaching family ties, though these elements get their fair share of pages. That is, he seeks first and foremost to understand his American experiences – via Hawaii, Los Angeles, New York and Chicago – through race and his evolving Black identity, even as he invites readers to witness these developments and dynamics from foreign – namely, Indonesian and Kenyan – vantage points.

On Chicago’s South Side… he noticeably matured in his relationships and as a person, symbolized by his preference to be called ‘Barack’ instead of his childhood nickname, ‘Barry’.”

The alchemy of race and racial identity that Obama spends chapter and verse discussing is fluid and volatile, though its protean nature and contradictions at times seem to escape his notice, or at least do not warrant further efforts at investigation. Obama the chameleon is on full display throughout the book. As he confides early on, “I learned to slip back and forth between my Black and White worlds, understanding that each possesses its own language and customs and structures of meaning, convinced that with a bit of translation on my part the two worlds would eventually cohere.” While trial-and-error experiences often tested his racial footing, he was exposed to enough laboratories of race, whether Hawaii, New York or Chicago, to gain a sense of their parameters and each place’s unique balance of possibilities and limitations.

In his book, Obama is generally realistic about the potentialities of race relations, and his reading of African American history, Malcolm X, and his own experiences, is typically informed and clear-eyed. Nonetheless, the book strikes some discordant notes, with Obama sporadically lapsing into a pessimism that obscures his ability to see across divides or to cross borders. “The emotions between the races could never be pure,” he writes about a particularly depressing incident. “Even love was tarnished by the desire to find in the other some element that was missing in ourselves. Whether we sought out our demons or salvation, the other race would always remain just that: menacing, alien and apart.” Such statements are in line with the stylistic sweep of the book, adding shades of complexity that both illuminate and darken the content and tone.

Barack Obama on the campaign trail in 2004. David Katz/Office of Senator Barack Obama/Wikimedia Commons

During the 1980s, Obama deliberately embraced an African American or Black identity. His college experiences on the mainland were an important part of this development, but his stint as a community organizer among economically distressed Black residents on Chicago’s South Side was particularly critical. He noticeably matured in his relationships and as a person, symbolized by his preference to be called ‘Barack’ instead of his childhood nickname, ‘Barry’. His writings convey a genuine longing for community of the sort that had not been available to him in Hawaii or Jakarta, where a minuscule or “lonely only” representation (as Joella Edwards termed her tokenism at Punahou) could never approximate the substance or value of true belonging. Immersing himself in the South Side and its many crises involving unemployment, health-care access, affordable housing, drug-related violence and failing schools moored him in a people and their communal concerns. However, being present was not enough to establish binding ties.

Obama came to believe that membership and belonging could be – had to be – earned. “In the sit-ins, the marches, the jailhouse songs, I saw the African-American community becoming more than just the place where you’d been born or the house where you’d been raised,” he opines in consideration of his experiences in Chicago. “Through organizing, through shared sacrifice, membership had been earned. And because membership was earned – because this community I imagined was still in the making… I believe[d] that it might, over time, admit the uniqueness of my own life.” To be sure, phenotype and ancestry did matter and could produce meaningful kinship, or at least durable connections and inclusion. In his 2006 book, The Audacity of Hope, Obama describes explicitly seeking to merge his own American perspective and experiences as “a black man of mixed heritage” with “generations of people who looked like me” and who “were subjugated and stigmatized, and [experienced] the subtle and not so subtle ways that race and class continue to shape our lives.” Still, individual agency, choices and psychological investment in belonging did count; these factors were the very sinew of community, its reason for being.

In later musings, Obama recognized that facets of his experience, whether the missing father or his “teenage rebellion”, were mirrored in the lives of the Black people that he worked with and for in Chicago. He also recognized that he was arriving at an African American identity in a “pretty roundabout” fashion and that he had even been compelled “to shape my identity, in some ways, on my own.” Such community imagining and self-crafting are, of course, circuits that lead back to his absent Kenyan father, his white mother, Indonesia, Punahou, and all of the features of his biography that convinced him that it was imperative to think of American Blackness (and communal membership) in capacious enough ways to hold his sprawling familial narratives and their far-flung points of origin. If moving to Chicago had not created an entirely new man, the journey had provided the tools and rationale for such a project of self-(re)invention.

Excerpted from The Black President: Hope and Fury in the Age of Obama (Johns Hopkins University Press, £26)

Claude A. Clegg III is the Lyle V. Jones Professor of History and African American Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. His previous books include An Original Man: The Life and Times of Elijah Muhammad (St Martin’s Press, 1997; University of North Carolina Press, 2014) and Troubled Ground: A Tale of Murder, Lynching, and Reckoning in the New South (University of Illinois Press, 2010). The Black President is published in hardback and eBook by Johns Hopkins University Press.

Claude A. Clegg III is the Lyle V. Jones Professor of History and African American Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. His previous books include An Original Man: The Life and Times of Elijah Muhammad (St Martin’s Press, 1997; University of North Carolina Press, 2014) and Troubled Ground: A Tale of Murder, Lynching, and Reckoning in the New South (University of Illinois Press, 2010). The Black President is published in hardback and eBook by Johns Hopkins University Press.

Read more

claudeclegg.com

@ClaudeClegg

@JHUPress

Buy at bookshop.org