Petina Gappah: Follow the body

by Mark ReynoldsWhen British explorer David Livingstone died in 1873 in a small village in present-day Zambia, he was accompanied by an entourage of around seventy African guides, porters and helpers, who came to the remarkable decision to carry his remains over 1,500 miles to the coast at Bagamoyo to be transported home for burial. In Out of Darkness, Shining Light, Petina Gappah takes up the story via fictionalised accounts from two of Livingstone’s real-life companions – seen-it-all cook Halima, and freed slave and Christian-educated scribe Jacob Wainwright. The film below captures the flavour of the novel, and is followed by a wider transcript of our chat.

MR: How long have you been fascinated by David Livingstone, and how have your impressions of him changed over time?

PG: That’s actually an essay-worthy question. It really started for me when I was a child, discovering David Livingstone in my local library, the Queen Victoria Memorial, when I was about ten or eleven. And our school did a lot of competitions with a school called David Livingstone Primary in town, so I was always aware that there was a person called David Livingstone, and he was very heroic to me because he was a heroic failure. The kind of books I read were all about these great British heroic failures: Livingstone and Scott and Shackleton. And so I actually wanted to be such a heroic failure – only I wanted to succeed. I wanted to be an explorer and look for the source of the Nile, but that was a childhood fantasy, I didn’t realise that the source of the Nile had been found! And then it was only when I was sixteen that we did the new History curriculum, which focused a lot on African history, and my attention moved from David Livingstone to his companions.

So your subject is not Livingstone’s expeditions but what happened after his death. What urged you to write about this coda to his life?

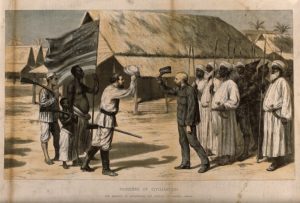

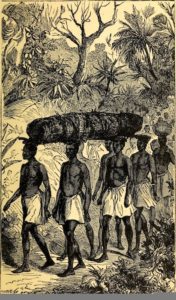

Livingstone’s body in transit, from Louise Seymour Houghton’s David Livingstone: The Story of One Who Followed Christ, 1882

I initially started to write about David Livingstone and his relationship with the companions, but the more I wrote, the more I realised that what really interested me was that journey – what happened to him after he died. Now I don’t know how much people know about David Livingstone, but he died on the first of May in 1873, in what is now known as Zambia, and his companions had a decision to make: what do we do with his body? There were no other white people about for them to consult, there was no consulate or anything like that, this is pre-colonial Africa. So they made an extraordinary decision to travel with his body from what is now northern Zambia to the coast of what is now Tanzania, to the port city of Bagamoyo. That journey on the map looks like a very short distance, but it took them about nine months to complete.

The novel switches between the observations of a sharp-tongued cook and the journal of a young scribe and would-be priest. What made these two stand out for you among Livingstone’s followers?

I chose to narrate the novel from the perspectives of two very different people. The first person is Halima, David Livingstone’s cook, and the second person is Jacob Wainwright, who was a freed slave. Originally the novel started out as multiple voices. I was very much inspired by William Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying, but the more I wrote the voices – I had about thirteen or fourteen voices – the more I realised that some of them sounded the same. One of them was actually David Livingstone’s voice, and another was his daughter in England. And then I thought to myself, the two most interesting voices to me are the cook and the scribe, so those are the two voices that I chose to focus on.

The joy for me in researching this novel is that David Livingstone was such a gossip – he loved writing about the people around him. He was a wonderful writer, and nothing escaped his attention.”

How much is known about the real Halima and Jacob, and how much in the novel is your own invention? What hints did you pick up from Livingstone’s journals and elsewhere?

Well, I tried to telegraph to the reader how very clever I was in my research (!) by getting excerpts from David Livingstone’s journals and putting them as epigraphs to the first part of the novel, to Halima’s chapters. I wanted the reader to understand that these were historical figures, they were actually real people who travelled with David Livingstone, and people that David Livingstone wrote about. And the joy for me in researching this novel is that David Livingstone was such a gossip – he loved writing about the people around him. He was a wonderful writer, and nothing escaped his attention, whether it was the quarrels of his companions, or the beauty of a particular young woman who had joined them. So what I ended up doing was to take those bits of the journal where he talks about his companions, and then flesh them out.

Handwritten extracts from Jacob Wainwright’s actual diaries were published by Livingstone Online last April, some time after you’d handed in the book.

I was absolutely gutted to find that they had published excerpts of the journal, it had actually been found, but at the same time I was also relieved, because I don’t know if I would have been confident enough to write an imagined journal if I had known that the real one existed. I’ve got an event on 19 March in Edinburgh, with the David Livingstone Memorial Trust, who are the repository of the memories of David Livingstone, and I’m going to go and look at the journal at last.

I read that there was a German translation of the original diaries in existence. Did you have sight of that at all?

No, no I didn’t, I came across it very, very late on in my research, it was translated by a historian called Roy Bridges, but by that time it was too late for me to make any real use of it.

James Chuma and Abdullah Susi will be known to some readers as Livingstone’s longest-serving retainers, and for having advised on the publication of his Last Journals. How have you modified their known public personas? And in what ways are those last journals problematic?

Chuma and Susi presented me with a real dilemma, because they are the only companions who speak, who are known about, who are acknowledged and acclaimed, and as you say they also contributed to the last section of the last journal of David Livingstone. But they were problematic to me because, even though they seemingly spoke, they were actually silenced. The story of the journey is narrated by somebody else and not by them. So I wanted them to be part of the journey, because obviously they were there, but I also wanted to highlight the other companions. I made them 69, because it’s a nice, poetic figure, but there were 72 or 73 people who travelled with Livingstone, and I wanted to highlight the others as well as Chuma and Susi.

Both Halima and Jacob are diminished and restless after the journey’s end when, as Halima observes, “there are now hundreds and hundreds of freed slaves roaming the streets… [facing] a life of banditry, ruffianry or starvation.” How might the British have improved on their model of abolition? And how did Livingstone himself believe things should pan out after slavery?

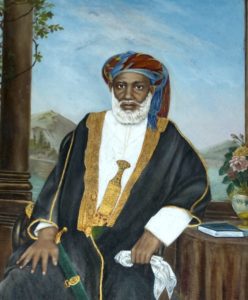

That is actually one of the most difficult issues that faced Zanzibar at that time, because the emancipation of the enslaved was so sudden and so quick. I got a lot of information from a memoir by one of the princesses from the Sultanate of Zanzibar, Emily Ruete, who married a German man. She writes about how difficult Zanzibarian people came to see the emancipation of slaves really was, because of course once people had been emancipated and freed they had no work, because employers, their former masters, didn’t want to pay them. So they were roaming the streets, they were homeless, and it was a very unsettled time for Zanzibar. But I don’t know what the British could have done, really, because they were not in control of Zanzibar at the time, Zanzibar was free and under the control of the Sultan.

Chunua Achebe contrasts Livingstone’s attitude to Africans to that of Conrad, who was born much later on, and says this makes Livingstone very special in that he recognises that Africans are as normal as everyone else.”

You quote Livingstone as noting that Africans “are just such a strange mixture of good and evil as men are everywhere else.” And that the cries of children “are the same in tone, at different ages, here as all over the world.” Do such sentiments qualify him as a pioneering humanitarian, or are they just a little patronising?

I thought a lot about whether Livingstone’s observation that Africans are as much a mix of good and bad as everyone was patronising, or whether that really made him stand out from his peers, and what helped me answer that question is that I first came across that quote in an essay Chinua Achebe wrote about Joseph Conrad, about Heart of Darkness, where Achebe contrasts Livingstone’s attitude to Africans to that of Conrad, who was born much later on, and says this makes Livingstone very special in that he recognises that Africans are as normal as everyone else. Of course there are other problematic passages in Livingstone’s journals, but that passage really does stand out, and I also love the passage where he talks about how the cry of children in the villages they go to remind those of the party who are fathers and mothers of the little ones they left behind. And to me it was passages like that that made it easier to sustain my interest in David Livingstone as a character. I started to imagine, what would it have been like to write about Stanley who was, to make the understatement of the year, a bit of a bastard. One of my friends who was writing a biography said to me that if you’re writing about a historical figure and spending a lot of time in the world of that figure, it really helps to be a little bit in love with your subject. So I’m very glad that in David Livingstone I found somebody, not that I was a little bit in love with, but I was really fascinated by him, and I was really intrigued by especially his relationships with his companions. I call him the first white man to go native in Africa, because he was very much at home with his African companions; more so, actually, than with the white fellow explorers that he travelled with.

I felt that Halima was a little bit in love with him…

Halima is a little bit perplexed by him, because she doesn’t understand why any man with all his five senses would actually leave his home to look for the beginning of a river. And that for me was the beauty of narrating the novel first from Halima’s point of view, because she’s more interested in people than in things like geography and the source of the Nile and all that kind of thing, so we see the camp, the expedition through her eyes and they are just people to us, and then Jacob comes in later with his more superior knowledge of the world, to locate us geographically as we travel on that journey. But yes, I would say Halima is a little bit fascinated by him, but also thinks him a bit of a fool!

Halima might not be educated, but she knows people, whereas Jacob Wainwright is so rigid, so absolutely certain of the rightness of his views, that he actually becomes the most unreliable character of the two.”

Just as there are different moralities and behaviours in any slice of human society, Livingstone’s followers are capable of anything from kindness and compassion to silliness, pride, lust, greed and even murder. Part of the fun of the novel is to view the actions of the same individuals through the eyes these two very different people: a mercurial gossip and a sanctimonious young man of God.

I love unreliable narrators, there’s just something about somebody who believes they are telling you the full story, when actually they only see half of it. That is very attractive to me as a writer because, I think, I’m a plot-driven writer, plot is very important to me, so using an unreliable narrator really does help to advance the plot because you want to leave the reader a little bit mystified about what’s actually happening. So the beauty of having two such blinkered characters – Halima is actually less blinkered in a way than Jacob Wainwright, because she’s utterly cynical about people, there’s nothing she hasn’t seen, because she’s been an enslaved woman in different households, she knows people. She might not be educated, but she knows people, whereas Jacob Wainwright is so rigid, so absolutely certain of the rightness of his views, that he actually becomes the most unreliable character of the two.

How would you say Livingstone’s legacy is viewed across central and southern Africa today – and in Zimbabwe and Zambia in particular? It seems those two countries are almost vying to claim him as their own.

Do you know what, I disagreed with my former president on a lot of things, with President Robert Mugabe, but one thing we agreed on was that Livingstone was a central part of our history that we could not erase however much we wanted to. In fact there’s a statue of David Livingstone at Munhumutapa Building where the president has his offices, and it overlooks the president’s motorcade, and I often asked the people I worked with in the civil service, why on earth is this still there? And the answer, apparently, is that Robert Mugabe wanted it there, because he said, what harm is he doing in the courtyard? He was just a humanitarian. So there’s that view of Livingstone, that he was a humanitarian, and because Africa, southern Africa especially, is probably 80 per cent Christian, he was important in Christianising the continent, and he was also important in eradicating the slave trade. In fact, I would say that is his one big success, which came posthumously, the closure of the Zanzibar slave market.

Do you agree with Kenneth Kuanda’s assertion that Livingstone was “Africa’s first freedom fighter”?

One of the most moving things I discovered when I was researching the novel is that on the hundredth anniversary of Livingstone’s death in Zambia, in Chitambo’s village, Kenneth Kaunda laid a new plaque on the grave of Livingstone’s heart, and he said some very lovely things. Livingstone’s legacy is helped in part because he wasn’t really part of the colonial project, he preceded the colonial project. In a way, he unwittingly paved the path to colonialism, but he wasn’t himself a colonialist. He talked about the ‘three Cs’ for Africa: one of them was Civilisation, obviously very patronising, the others were Christianity and Commerce. He wanted to establish trading posts to replace the slave ports. He believed that if Africans were able to trade in products beyond slaves, it would help the development of the continent. So he had some very interesting ideas about Africa, and because of his role as a missionary, even though he was a failed missionary in the end, his role in Christianising Africa, his translation of the Tswana Bible and so on, is seen in a much more benign light than someone like Stanley or Mungo Park in Nigeria or any of those people.

One of the ways the British Navy fought the slave trade was to run blockades just off the shores of Africa. And of course the dilemma was then, what happens to these people when they have been rescued?”

Is there anything murky about his association with the slave and ivory trader Tippu Tip?

Do you know, one of the most fascinating episodes in the life of Livingstone is that on at least two occasions, he was rescued by slave traders, and one of them was Tippu Tip, whose brother Kumbakumba was also a fairly well known slave trader. One of the things I regret is that I didn’t really focus on that aspect, because of course it happened when Livingstone was alive, and my focus was on Livingstone’s body after his death. It must have been such a burning humiliation for him to accept help from the people whose trade he called “the odious trade in human flesh.” It must have been the ultimate humiliation to have to accept the help of slave traders, but I think that’s one of the things that, to me, makes David Livingstone such a layered and complex character to write.

Two things you really do focus on are the East African slave trade, and the group – including Jacob Wainwright – who are freed slaves schooled in Christianity by the British in India, which is tied in with that trade. This was all new to me.

That is something that was new to me too. We had studied the slave trade at school, and of course I’d read about slavery in East and West Africa, but there were little details that were unknown to me. For instance, when Britain abolished the slave trade in 1807, and then slavery itself in 1833, the trade was still continuing, slavery was still an institution in many parts of West Africa, East Africa, the Caribbean, and so on. So one of the ways that the British Navy fought the slave trade was to run blockades just off the shores of Africa on the Indian Ocean, and in West Africa the Atlantic Ocean, and they had these ships that used to patrol the coast to recuse slaves who had been taken. And of course the dilemma was then, what happens to these people when they have been rescued, what happens to these freed slaves? Because for a lot of them, of course, they couldn’t remember where home was, or even know where home was, because you’re now suddenly out on the Indian Ocean and you’ve been taken from Malawi or Mozambique or wherever. So the solution that the British found was to establish a school in the principality of Bombay, which was then under British control. The school was called the Nassick School, and it was such a fascinating place because these, especially the young men who were taken there, they were trained in carpentry, they were given skills like shipbuilding, cartography, they were taught to read and write in English, they were Christianised, and then when the explorers were coming through India to refuel and restock, they would pick up some of these boys and take them back to Africa as their companions. And Jacob Wainwright is one of the boys who was rescued and educated in this way.

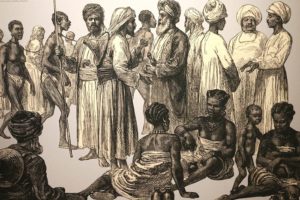

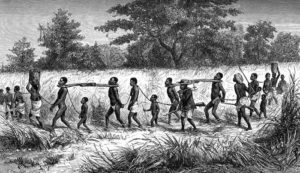

‘Gang of Captives met at Mbame’s on their way to Tette’ from David Livingstone: Narrative of an Expedition to the Zambesi and Its Tributaries. John Murray, 1865

This band is crossing a pre-colonial landscape, before European-imposed national borders, and it’s a land peopled by feuding tribes, kingdoms and clans, where villages are named after local chiefs. It’s little wonder that those rivalries continued long after the European carve-up…

One of the things I found really fascinating as I researched this was to understand what Africa looked like before colonisation. There were big kingdoms in different parts of Africa, and there were also smaller chiefdoms, if you can call them that, and as you say there were a lot of ethnic wars and what people might call tribal wars and so on, there was this big menace coming from the south, the so-called Mazitu, who are these Ngoni groups related to Shaka Zulu’s ethnic group who were marauding throughout southern Africa, who were given different names in the different languages. So it was a time of great uncertainty, and in fact the great Mfecane, as it’s called in South Africa, the splintering of the Zulu kingdom and the great migration of the Zulu from what is now Natal up to Mozambique, to Zimbabwe, to Zambia, to Botswana, happened during that time. It’s fascinating to me that Livingstone met Sebetwane of the Makololo, a Zulu king who had fled from the wrath of Shaka Zulu in the south. That’s maybe a level of detail that a lot of readers might not know, but for me it was really very interesting to see that Livingstone was recording what was happening in pre-colonial Africa at this time of great upheaval.

My novels from now on are going to be historical in theme, because I’m fascinated to explore those little corners of African history that haven’t really been talked about.”

We ought to talk about how long it’s taken for you to write this book…

Can I show you something? [she holds up a floppy disk] I have removed this from its frame. This is the first version of this novel, I called it Mwili wa Daudi, which is Swahili for ‘the body of David’. I wrote it first in 1998 and I was really proud of myself. This is what I call the Faulkerian version, with all the different voices. But the more I wrote, I realised that I really didn’t know that much about the period. I was just writing these people as characters without really locating them in the geography of the place, without understanding anything about expedition life. So I thought, hmm, maybe let me do a bit more research. But also I didn’t really trust myself as a writer, it seemed like a hugely ambitious project, and to have it as my first novel seemed a little bit too ambitious for me, so I exercised my writing muscle by writing other things before finally turning to this one as my fourth book.

Your recent story collection Rotten Row is in a very different vein, tackling themes of crime and law in contemporary Zimbabwe. So what other contemporary and historical fiction are you planning? And which periods of history particularly tempt you?

Do you know, I think Rotten Row is probably the last book I will write about contemporary Zimbabwe, because I think I’m done with contemporary Zimbabwe as explored through short fiction or novels. I’m now writing plays about contemporary Zimbabwe, my first play was staged just last year, also called Rotten Row; I adapted four of the stories in the book to write a one-hour play. My novels from now on are going to be historical in theme, because I’m fascinated to explore those little corners of African history that haven’t really been talked about. So at the moment I’m writing what I call my Rhodesia trilogy, as opposed to my Zimbabwe trilogy, which were my first three books, and the Rhodesia trilogy looks at different members of a black middle class in Rhodesia, from a time of the Mutapa Kingdom in the 1400s, up to about 1978 or so.

Where has your other career as an international lawyer taken you in recent years?

I’m currently doing a panel in the WTO, arbitrating a world trade dispute, which is very hush-hush and I can’t talk about it. I’ve also recently been an adviser to my government on a new trade and investment policy, and in a way it’s wonderful to be a retired lawyer, because it means that I can focus on being a full-time writer. But at the same time, when I get bored, I do like to go back to doing legal issues. I teach at an institution in Narusha in Tanzania, for example, I teach African trade diplomats. So it’s nice to dabble, to go back and forth.

“A powerful novel, beautifully told.” Jesmyn Ward

Petina Gappah is a Zimabwean lawyer and writer. She is the author of the story collections An Elegy for Easterly and Rotten Row and the novel The Book of Memory, and the recipient of the Guardian First Book Award and the Society of Authors’ McKitterick Prize. As a lawyer she specialises in international trade and development, and lived and worked in Geneva for many years. She is now based in Harare. Out of Darkness, Shining Light is published by Faber & Faber.

Read more

@VascoDaGappah

@FaberBooks

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.

@bookanista

wearebookanista

Watch Petina reading an extract from Out of Darkness, Shining Light

Read our interview with Petina about her previous novel The Book of Memory

Read an extract from the story ‘The Old Familiar Faces’ in Rotten Row