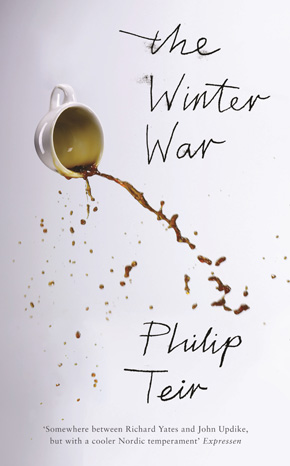

Philip Teir: Question everything

by Mark ReynoldsPhilip Teir’s debut novel The Winter War chips away at Scandinavia’s much-trumpeted model society by examining individual lives in a well-to-do but barely functional Finnish-Swedish Helsinki family as they scrabble for meaning and identity. Max Paul is a retired lecturer on the point of turning 60, who is working on a biography of pioneering sociobiologist Edvard Westermarck. His wife Katriina has a well-paid job in health management, while daughters Helen and Eva are respectively grappling with the early years of marriage to a dull husband and life as a mature art student in London. Cracks in the Paul marriage begin to show when one of Max’s former students, now a journalist, turns up and expresses the desire to interview him, and seemingly presents an opportunity for seduction.

MR: The opening line of the novel is: “The first mistake that Max and Katriina made that winter – and they would make many mistakes before their divorce – was to deep-freeze their grandchildren’s hamster.”

So my first question is, were any hamsters harmed in the making of this book?

PT: People sometimes ask authors if anything is true in the book, if it was based on real life, and I would say that the only thing I took straight from my own life is the names of the hamsters, because we used to have hamsters in my family called Blixten and Skorpan. But no hamsters were harmed, no.

Of course what that opening does is foreshadow the end of the book, revealing that Max and Katriina are going to split up. So what were you aiming to set up in terms of the tone and scope of the novel by beginning in that way?

That sort of opening is not the first thing you write. I wrote that very, very late in the process, when the book was practically finished. But I really like the way some writers open books giving an expectation of what’s going to happen. You don’t have to say very much, but in terms of the story arc it’s very effective when you have some sort of expectation when you start reading, and that’s what I was looking for. It’s one of those very lucky things that suddenly I just had that line in my head. There’s a lot of examples like that in literature of writers combining two very unexpected things in the first line, and that was what I was going for, to have those two ingredients where you don’t know right away what they have to do with each other, but as you read on you get the story.

Again, quite early in the book there’s a nice description of marriage from Katriina’s point of view, which goes: “Katriina viewed marriage as a form of reciprocal tyranny, like living in a highly functional totalitarian state. There weren’t many options, but as long as you kept to yourself and didn’t challenge the status quo, it works fine.”

How does this fit with Edvard Westermarck’s understanding of marriage? And are his observations now completely outdated?

Westermarck was writing his research on marriage just when it was changing. If you read his book The History of Human Marriage, he discusses in the later chapters how marriage is no longer something that is imposed by society, that you can now get married for love. This was the 1890s, and he was active until the 1930s. He discusses those things, so he was modern in a sense. With Katriina and Max I think they have what a lot of married couples have, where people can be pretty happy if they have money, and don’t really have to worry about politics. They can be happy if they just don’t start poking into some of the issues they have in their marriage, and that’s I guess how a lot of us live our lives. We know that we might actually need to discuss something, but if we keep our eyes closed we can stay happy.

Which leads neatly into the questioning of typical Scandinavian liberal ideals, for example where Max asks Laura: “Who wants to live in a society in which everything is organised according to the concept that no one acts inappropriately or feels bewildered; nobody goes too far or follows his emotions or does anything in direct contradiction of all the rules?”

How is that liberal society being dismantled – for better and worse? And how are things different in Finland compared to the rest of Scandinavia?

I think Finland compared to Sweden is quite different – like with the Julian Assange case, when he said Sweden is like the Saudi Arabia of feminism. I think what Max is saying comes a little bit from that perspective; he thinks that if you have gender identity politics which question the idea of the norm – the conventional marriage or whatever – there’s always also something normative in that. And I think he’s seeing it in his work, he’s seeing young people coming in and making everything into identity politics.

If you can’t question everything, then you end up with this totalitarian idea of how things should be. Max feels that young people are too rigid in their political views.”

That’s a very central line in the book because it really dives into the last five or ten years of discussion in Scandinavia, for example in literary discussion, that has been very much about identity: can a white heterosexual male write books about immigrant experiences, and so on. Max was young in the 70s and he was there when the feminist movement came, he experienced all that, but he thinks it’s too rigid now, everything is locked in: you can do that, you can do that and you can do that. What he’s saying is that if you can’t question everything, then you end up with this totalitarian idea of how things should be. I think his argument is very typical for his age, and for professors his age. He feels that young people are too rigid in their political views.

Laura’s views and opinions are fairly unremarkable and malleable, yet she is considered a bright new voice in journalism. Does she have anything fresh to say?

She’s a little bit cynical, an opportunist. But she’s young and inexperienced. I can picture myself as Max being interviewed by Laura, and realising that she doesn’t know that all the discussions people her age are having are the same as people had in the 70s. And he’s frustrated that he can’t really show her that he knows what she’s talking about, and that their views are not really connecting.

She writes a newspaper column, and that got me thinking about just how much original thought can actually be circulated in the mass media. The public interpretation of Max’s academic studies on relationships sees him dubbed the ‘sex doctor’, which is not substantially different from (as you have elsewhere) someone commenting on Laura’s byline picture that she probably has nice tits. Is the mass media guilty of dumbing down the population?

The problem is there’s only room for one narrative. For example if I were to write an article about Finland, even for Swedish readers, some topics are typical: the Finnish education system, the terrible cold winter, and maybe Santa Claus. It’s really hard to try to nuance everything, and that’s one of the reasons why I write fiction, because it’s much easier in fiction to look at the bigger picture than in journalism.

Finland is a young nation in terms of having an independent identity. What have been the major societal changes between your father’s generation, your own, and today’s students?

Again, that’s a very central theme of the book, it’s really about contrasting generations. What is the idea of happiness, for example, for these different generations in Finland? My father is about Max’s age, and I’m about the same age as Eva, and then my family background is sort of the same as the father’s in the book. His parents were the post-war generation, and the way of living in just two generations has changed a lot. It’s probably very similar in England.

Max’s generation was the first to go to university, and after that Eva’s generation is the middle-class, young generation that wants to be in the arts or the creative industries because that’s what their parents still couldn’t do. Eva’s father Max is encouraging her to do art in London even though she doesn’t really know what she’s doing. When I thought about her character, I thought about interviews I sometimes see in the local newspaper with 30-year-olds coming home for the summer who tell the interviewer about their amazing life as a design student in Berlin, or doing clothing design in Paris. I always thought there’s something strange about that. It’s like an industry nowadays, people paying a lot of money to go to study art in London or something just so you can say you did it. But what’s the point? It’s such an expensive city, and it’s not a very glamorous life. I think Eva’s probably the most unhappy person in the book, but then, typical of her generation, she even enjoys being unhappy because it means she has a possible subject for her art. But it’s about the very fast change. This is the first generation who don’t have it better than their parents.

The title of the novel references the Soviet invasion of Finland. How does that battle, and the impact of World War II, still resonate in Finnish society?

A lot, especially in Finnish literature. One of the main reasons I called the book The Winter War is that when I started to think about writing a family saga, I realised pretty quickly that the family in the book would have some kind of background in wartime Finland, and I needed to decide what Max’s parents’ background would be. Then it sort of became the working title of the book. There have been so many writers, even young writers, writing about the war experience in Finland. I didn’t want to go into the archives and start reading old newspapers, because people have done that already and you’d really need a fresh angle. But I had the title and I thought maybe, you know, like Alan Alda says in Woody Allen’s Crimes and Misdemeanours, “comedy is tragedy plus time”. I thought maybe it’s time now to use The Winter War as a metaphor. Finland is such a young nation, people are still trying to figure out its identity, in a different way from what people might be doing in England or elsewhere.

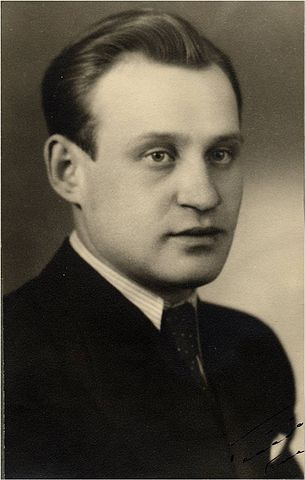

Väinö Linna in 1947. Wikimedia Commons

Väinö Linna’s book about the war years The Unknown Soldier, which Helen is introducing to her students, is a novel without a central character too. Is it a book that influenced your approach to this one?

Actually, Helen’s struggle with that book is taken very directly from my experience of reading it. I read Linna’s trilogy about rural Finland, Under the North Star, which I really enjoyed, but The Unknown Soldier I never really got into. As you say, there’s a lot of characters, but I don’t think that book influenced me. It was something I thought would be nice to put into the book to make the war a reference point.

In the course of looking up Linna’s book, I saw that Penguin Classics are releasing a new edition in April (retitled Unknown Soldiers), which they say is “the first faithful English translation”. An English translation has been out since 1957. Do you happen to know why that version might be flawed?

I only read it in Swedish, but the thing about the book is there’s a lot of dialects; the soldiers come from different parts of Finland and Linna used different dialects. When it was translated in to Swedish, there was no equivalent to the Finnish, so the translator decided to use Swedish dialects. So I guess what is faithful probably has a lot to do with how they talk in the dialogue.

You describe Finland as an over-eager member of the European Union since it joined in 1995. So what were your thoughts when Prime Minister Jyrki Katainen stepped down last summer to become EU Vice-President? And how is he getting on in the new job?

First of all, for a long time he was really, really tired, and fed up with the job because he’d formed a government with people from a lot of different parties, and he was telling journalists how they’d be up till two in the morning making decisions and he only slept four hours. He was looking really tired, so everybody knew that it was a relief for him when he decided to quit.

There was an election for party leader, so he had to make a decision even though the Finnish election is not till next April. So a new prime minister came in for less than a year and we don’t what’s going to happen with him. But the new one, Alexander Stubb, has the same politics. He already had his EU time, and he’s the kind of guy I think that goes home at 5 and goes out running, and then sleeps very well. Like I say in the book, Finland has been like the good student in the EU, and I would think that we have a pretty OK reputation, and people are probably listening to Katainen. I think he’s very well integrated into the whole EU system.

The Occupy movement plays a big role in the London episodes of the book. When the camp outside St Paul’s is moved on, Eva reflects: “… it was sad. The fact that there was such a thin line between the two options: worldwide revolution or total oblivion.”

The protesters still keep trying to set up camp in Parliament Square and are constantly moved on or stopped by the police, so it does feel a long way from an effective revolution. Do you think movements like that can make a difference?

I think it probably did make a difference. The thing that’s important is the symbolic gesture. It’s democracy. But like the former Soviet Union nations trying to become democratic societies, there’s a lot of tedious and boring work involved. I interviewed people who were there, and very early on there were a lot of practical issues that took a lot of energy, and became almost a job for them, organising electricity and food and everything you probably don’t think about in the beginning. For a lot of people, the experience was probably very important and useful. But in the final analysis, they never decided on any demands.

To jump to some other random topics and observations, modern interior design is a matter of conflict in the marriage. Katriina wants things “orderly and tidy”, while Max despises “throwing out all things old and human”. Should we always look to choose traditional crafts over mass-produced consumer goods?

I guess it’s parallel to what Max is saying about identity politics, that people shouldn’t be so rigid. He thinks that everything should have a personality, a story, and not be so locked in. Max is the kind that really hates IKEA. It doesn’t necessarily reflect my own views, but I enjoy going into characters’ heads and trying to imagine how they think about things. Also he seemed to like Darwinism, and theories that our idea of beauty might come from human history in Africa and the natural landscapes there. I like working with that, and sort of mixing it all up with contemporary topics.

Helen’s husband Christian is “unmistakably a Finland-Swede in the typical Helsinki style: well-mannered, always willing to help, and so polite as to be slightly boring.” What else characterises Swedish Finns, and what stereotypes would they prefer to shake off?

A lot of Finnish Swedes, especially in Helsinki, live in bilingual families, where the wife is often Finnish-speaking and the husband is Swedish-speaking. I guess the thing Swedish Finns most want to shake off is the idea of a bourgeoisie, that everyone has that kind of background. There is a bit of that in Helsinki, families that have been part of Finnish aristocracy for a long time. But then you have the whole west coast that’s mainly farmers and fishermen, and of course there are small-town, suburban pockets too. I wanted to write a middle-class story, and I don’t think the Paul family is typically Finnish-Swedish, this could just as well be a Finnish family in Helsinki, or a family in Berlin or London.

Why did you decide to extend the geography of the novel to include London – and Manila?

I think if you want to portray a typical upper-middle-class family today, especially in Helsinki, you would probably have a daughter studying in London or some other European city. My sister, for example, lives here. She doesn’t study art or anything like that, but she lives here. With the Manila thing, my mother has sort of a similar background. She hasn’t been to Manila recruiting nurses, but there are a lot of projects like that as Finland tries to do something about the demographics of an ageing population with not enough carers. In Finland at least, you don’t read a lot of books about work. I wanted to write about about modern work, and I wanted to find something that was pretty hard to do, something that wouldn’t be the most obvious.

I guess it is a tough sell for Katriina, when one of the supposed perks of the proposition is the chance to learn Finnish. It’s not exactly a transferrable skill back in Manila…

But these projects do exist, and I did interview some people in this field. But most of it I just made up.

Finland is still very restrictive with asylum seekers compared to Sweden, which is obviously at the other end of the spectrum. The political question is, what is Finland doing to help people in need? And I think we’re not doing enough.”

How much of an issue is immigration in Finland compared to other Scandinavian countries?

Finland was for a long time very restrictive, and is still very restrictive with asylum seekers compared to Sweden, which is obviously at the other end of the spectrum. Sweden also generates more immigrants, because if you have a lot of families from Syria, say, living in Sweden, more Syrians want to move there because they have family, and in Finland you don’t have that. But I think Finland is comparable to most Western countries because Helsinki in another twenty years is going to be twenty or thirty percent people born outside of Finland. It’s students, people moving for work or whatever; that kind of immigration is going to happen anyway. The political question is, what is Finland doing to help people in need? And I think we’re not doing enough.

How do you feel about comparisons of your debut novel to the work of Jonathan Franzen? And which international writers do you particularly admire?

I guess it’s flattering to be compared with Jonathan Franzen. I think it’s accurate in the sense that the sort of composition with four main characters is at least typical for the two novels of his that I’ve read. But I think there are British influences too. I’ve read David Lodge who has these professor types, and Ian McEwan’s Solar is a little bit similar with the professor at the centre. I really wanted to write that kind of novel, set in a Finnish context.

Which other Finnish writers should we be reading?

You should read the Tove Jansson short-story collection that was just released by NYRB Classics, The Woman Who Borrowed Memories. I think they have been published before, but not in one book. She’s really one of my absolute favourite authors, and she really has been very important for my writing. People don’t know her adult writing so much.

Sort of Books recently published her first collection, The Listener, which has some of the same stories, and I read that. In fact, we ran one of the stories, ‘The Rain’ on Bookanista.

Then there’s this Finnish author now who is really happening called Katja Kettu, her most famous book is The Midwife. She’s an author there’s a lot of talk about, who will soon be available in English (the rights have sold to Amazon Publishing, and a Finnish film adaptation will be released in September 2015). Sofi Oksanen I also really enjoy, her book Purge came out a couple of years ago. Then there’s the Finnish-Swedish author Monika Fagerholm, who wrote The American Girl, that’s also really good.

How do you see yourself at 60?

Well, I think this is a very good handbook for anybody who is going to turn sixty! You know, here are the mistakes you might make and should avoid. I really liked being in the head of Max, and hopefully I learned something. I actually thought a lot when I was writing about becoming older, and I think all the clichés that we read about, a lot of us experience them first-hand, it’s really hard to avoid a lot of the clichés in life. That’s why I use a lot of clichés in my book, because I just think life is like that.

What have you been writing since, and what can we expect to see next?

I have two manuscripts that I’ve been working on in parallel, but there is a novel, and hopefully it’s going to be out in Swedish and Finnish in 2016. It’s also about a marriage, but it’s a longer scope, like twenty years. It’s not a longer book, but it’s different in temperament, and it focuses on only two characters, the wife and husband.

Philip Teir’s poetry and short stories have appeared in anthologies including Granta Finland. He lives in Helsinki with his wife and two children. The Winter War, his first novel, saw him compared by Finnish and Swedish reviewers to authors including Jonathan Franzen, Richard Yates and Julian Barnes. It is now published in English by Serpent’s Tail, translated by Tiina Nunnally.

Philip Teir’s poetry and short stories have appeared in anthologies including Granta Finland. He lives in Helsinki with his wife and two children. The Winter War, his first novel, saw him compared by Finnish and Swedish reviewers to authors including Jonathan Franzen, Richard Yates and Julian Barnes. It is now published in English by Serpent’s Tail, translated by Tiina Nunnally.

Read more.

@philipteir

#Scanzen

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.