Towards a poetics of wreckage

by Mika Provata-CarloneThere is something thrilling about a beautiful book – a book whose aesthetic, material presence, and the evocative momentum of its ideas and the words that embody them, seek to touch a reader’s every nerve, even that insubstantial vital centre we call our soul. Susan Stewart’s The Ruins Lesson: Meaning and Material in Western Culture aspires to be just such a book: sumptuously created, powerfully eloquent, grippingly intelligent. You’ll know from the first lines of the preface (actually from the three words, “new, tender, quick” of the dedication, quoted from George Herbert’s ‘Love Unknown’) that this is a supremely intellectual and spiritual, deeply human meeting of minds and experiences, across and in time, that is not to be missed. It is certainly not an encounter to be trifled with: it lives up to each of the promises of its title, namely to face frontally and try to comprehend the ravages of catastrophes, deterioration and devastation; to seek, and to believe in, meaning and its communicability; to reaffirm the value of a Western historical experience and its cultural inheritance as an inexhaustible, vital and living source of lessons for our present state of humanity. Passive reading is strictly forbidden (it would be, in fact, anathema, or to use the term most associated with the mistreatment of ruins, a desecration). The Ruins Lesson is an irresistible dialectics on culture, on values, on what makes us sentient and cogent beings in defiance of, or in a timeless contrapuntal harmony with, time itself. And by time, Stewart unequivocally means a consciously meaningful existence. The Ruins Lesson is a critical dialogue with diachronicity and synchronicity, with the feeling of a place of belonging, with the disjuncture or the creative syncretism of anachrony, with others and ourselves.

Stewart is in turns beguilingly and formidably poetic, philosophical, meditative, an unflinchingly analytical historian and critical reader of texts and objects, cultures and the socio-politics that have tainted them or shaped them, of the forces of creation and transcendence, destruction or disruption that have made us, or hindered us. For Stewart, The Ruins Lesson is a “meditation on the Tower of Babel”, an exemplum and a trope to which she returns time and again, in order to explore the hubris or the holiness of meaning and human creation, the notion of human endings and beginnings. Throughout human history, our encounters with ruins have been no less than engagements with mortality and eternity, with the very worth or Wyrd (fate) of life, to use the term Stewart retrieves from the Old English poem ‘The Wanderer’ – for ruins, Stewart will argue, are also like Joyce’s Wandering Rocks, the one episode in his Ulysses without a Homeric precedent: surfeit with referential rootedness, and yet errant and unknowable. Ruins have an a priori epic or elegiac quality. Quite often, they are even vested with both: “ruins, like trees, live beyond us and raise the haunting thought that what we have made may outlive us, even as a species.” Stewart is in thrall to ruins and their mesmeric power; she is also keenly alert to their Ozymandian symbolism, the lessons they so pithily – and Pythia-like – conceal for us.

For Stewart, ruins are at the boundaries between nature and human artifice, materiality and transcendence, time and eternity, chaos and meaning, Fall and redemption.”

Ruins are remnants but also starting points; they are both present and absent; they are enduring aesthetic models, or the tragic witnesses of failure and decay. They “speak to the resistance of human effort against nature”: a ruin is a thing (in Western culture, it is even an animus) destroyed, but it is also a survivor. “If Rome is eternal, it is not because of the permanence of its forms, but because it has endured so many cycles of destruction and rebuilding.” For Stewart, ruins are at the boundaries between nature and human artifice, materiality and transcendence, time and eternity, chaos and meaning, Fall and redemption.

Architectural ruins, a vision by Joseph Michael Gandy, 1798. Sir John Soane’s Museum

In setting out audaciously and ambitiously to chart a history of the materiality and material techniques of ruins, from original construction of the unruined whole, to spolia, conservation, restoration, re-antiquification or architectural rehabilitation, Stewart takes enormous delight in tangentials – most, if not all of which lead to wondrous peregrinations, and reveal an exhilarating mastery of scholarship in an almost infinite array of fields, as well as the ineffable connections and interrelations between them, real or metaphorical. Stewart possesses a superb Renaissance mind, and an intellectual fearlessness that allows her to deliver what is no less than a series of magisterial lectures on a cornucopia of variations on her chosen theme of ruins. In her schema, Beowulf is also an encounter with Britain’s Roman ruins; epic poetry reflects the ruins of epic action, as evinced through close readings of the Iliad and the Aeneid. Total ruins emerge as archetypal evidence of divine justice, as they do in Virgil, the Old Testament, the Greek myth of Deukalion. Renaissance nativity scenes such as those by Botticelli, Piero della Francesca or Dürer, with their landscapes of ruins in the background, are not only religious images and reflections on the sacred and the human, but also allegories of what emerges as a ruins trope: the old pagan, Imperial Roman world has crumbled, as the New Life is born. Ruins become a poignant topos of female narratives and feminist readings, as Stewart demonstrates through her exposition on the Hypnerotomachia, “one of the most exquisite material objects of the Renaissance”, and her study of the language of ruination attached to women (fallen/ruined), through the ‘ruined’ first human dwelling, the womb. Nymphs, social archetypes, theology and literature are explored as female narratives of ruination or its opposite, the Derridean topos of the virginal, the untouched, the ur-textual. The culmination of such a female perspective into ruins theory is the destruction of Marian icons during Iconoclasm and the Reformation. Language itself becomes a witness and the victim of ruin, as it undergoes changes, and is transfused by foreign elements.

Whether we admire or condemn them, seek to preserve them or destroy them, our reflection on ruins is also a tacit declaration that we can possess the past, both materially and conceptually.”

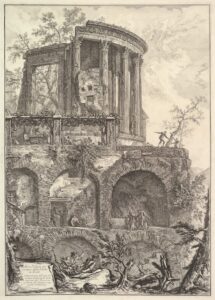

Altra veduta del Tempio della Sibilla in Tivoli by Giovanni Battista Piranesi, 1761. Metropolitan Museum of Art

There are fascinating analyses of our attitudes to ruins throughout time, starting with graffiti and inscriptions, which are not simply informational annotations, or dialectical commentaries, but also a way of ascribing or denying ‘age value’ to ruins, of acknowledging or disclaiming their history and identity. From agonistic destruction to idolatrous adoration, from ideologic appropriation, kitschification and monumentalising, to sacred veneration, to archaeology and narratives of a people’s being and identity, our engagement with ruins reveals as much about the past, as it does about the present. Our perception of ruins, our judgement on them, as the vestiges of past lives and actions, also codify what seems to be a continuous theme and motive in human history – and, arguably, not only in the history of Western civilisation: whether we admire or condemn them, seek to preserve them or destroy them, our reflection on ruins is also a tacit declaration that we can possess the past, both materially and conceptually. That we can define it, alter it, selectively extract and import its shapes, shadows, echoes, and above all its narratives of domination or subjection and defeat, alienation or belonging.

Starting with Pope Sylvester and Gregory the Great, and their distrust of a Classical past and its material presence, moving on to Petrarch’s famous zeal for a recovery of the classical tradition, and to Albrecht Dürer, who lamented that “as an artist he had been ‘robbed’ by the vehemence of iconoclasm against the pagans” of the ‘teachers’ he could have found in ancient artists, but also to Fazio degli Uberti and his Ditta Mondo, the Epos of the World, a dirge on the loss of classical culture, or to Manuel Chrysoloras, who would bring Greek and Greek texts to the West, and would write in turn to the Emperor of Byzantium about Rome and its ruins, and then to Pope Eugenius IV, who sponsored a survey of Roman ruins, which would lead to the legendary De Re Aedificatoria by Alberti, or to Pope Leo, who asked for a reconstruction on paper of Imperial Rome, and to Biondo, the precursor of architectural restoration-as-rehabilitation, then finally and breathlessly coming up to the ‘anticomania’ of the 18th century, and the travellers-looters of the Grand Tour, as well as their poets, Stewart offers a gripping survey of the politics and symbolisms of ruination, re-edification, monumentalising and re-memorialisation, of the history of history as a discipline, but also as a process of historical othering, and re-historicising.

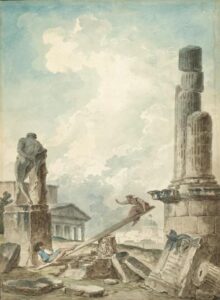

A Capriccio of Roman Ruins with Peasants in the Foreground by Charles-Louis Clérisseau, 1773. Private collection

Even printmaking in Stewart’s hands emerges as a “process of ruination”, due to the material particulars of its techniques, in what is rather an extravagant extension of the term, given that one can argue that sculpture, drawing, weaving, sewing, anything that gives shape to or alters the shape of a material, is a ruination of its original structure and form – even writing, from first scribbling, to cypher-worthy palimpsest… Yet it is such intellectual extravagances that transform an art-historical and socio-cultural analysis into an enthralling journey, a felicitous wandering across European landscapes, cultural and geographical, across timelines of history, in search for those nodal moments in time that made or broke our world. Poetic licence as regards how liberal the ruins category can be, becomes an inspired à propos for a meditation on the evolution, revolutions and contradictions of Western culture and civilisation, its multiple modalities, its resistance to a single experience, or to a homogenous, single identity or fate, at the very time that it has sought the transubstantiation of identity, whether as nationalism, or as one of many variants of distinct consciousness in an ongoing dialogue of coexistence.

For the Greek Manuel Chrysoloras, artefacts, icons, ruins “are not history, but direct and personal observation (autopsia), and living presence (parousia) of all the things that happened” at the time of their creation; they are, in his view, endowed with a particular life force, and should be seen as the embodiment of lived, and especially of living traditions. Ruins, for all their static connotations, are inextricable from flux, from a constant process of genesis, maturation or decay, regeneration. And this is perhaps one of the (few, yet arguably crucial) criticisms one can make of The Ruins Lesson: namely, that Stewart often speaks from a perspective of dislocation, alienation and severance from such a lived and living tradition, whose continuity and identity to all that it contains depends vitally on its ability to grow dialectically, exploratively, innovatively, and to evolve organically. There is a sense, again, of an a priori, this time that ruins are by definition membra disjecta, and that any attempt to locate them, localise them, see and feel them in, and as being of, their place, suggests “an ethnocentric notion of legality”. This sense of abstraction, detachment and objectification, which runs not in parallel, but antagonistically to the notion of objectivity, persists even as Stewart exposes, scathingly and rather brilliantly, the politics of appropriation and dispossession underlying the practices of spoliation, imperialising collecting, or even commercialisation. She condemns with ironising language the ‘legalised’ looting of both Greece and Italy in the 18th and early 19th centuries, quoting Quatremère’s famous position that ruins have an inalienable relationship not only with their geographical and social space, but above all with “their entire contextualisation in the memory of the people”.

Perhaps at the source of this critique is the very theoretical apparatus through which the past seems to be primarily perceived. That involves the notion of reception, so current in most discussions of any engagement with the past, and which has replaced (rather polemically) Aby Warburg’s concept of cultural Mnemosyne, or Nachleben. Warburg’s term presupposes a creative and organic, dynamic anachrony, a past that transfuses the present, even as the latter is transfused and redefined by the former. Reception, on the other hand, presumes on a certain critical level a quasi-autonomous object which is transferred or passed on, both altered and pristine, yet always neutralised, a foundling in a constant state of unclaimedness. In order to have reception, one must assume a process of cultural delegation, a tributary act, almost, not simply by the past to the present and the future, but essentially by one cultural paradigm (or people) to another. It entails principles of legators and legatees – as well as death certificates.

An extraordinary book… an unfailingly engrossing, formidably complex essay on art, permanence and impermanence, meaning and agencies of meaningfulness, pastness and the question of whom it belongs to.”

Much of the problematisation of this debate is inherent in Stewart’s analysis, especially in terms of embedment, or even in terms of artifice and artificiality, fake ruins, or the famous fabriques, where made-up or make-belief ‘ruins’ were installed in highly curated landscaped gardens. Such fabriques perhaps functioned as the ‘skulls’ in ‘living’ vanitas tableaux, or in turn as appropriated tokens of an ersatz historicity and permanence, in what would be now a new social landscape and stage… The question of a received history, culture, memory, is certainly at the heart of Germany’s negotiation of critical remembrance and expiatory forgetting, of reintegrating vitally, but also reflectively, the traces of an annihilation, as in Berlin’s stumbling stones, or Stolpersteine. In this sense, the non-inclusion in Stewart’s discussion of what Alison Shell has termed “sacrilege narratives”, i.e. stories where “sacred stones cry out against sacrilege, calling down divine vengeance on the perpetrator” and which were “attached to ruined abbeys, martyrs’ relics and other highly visible signs of Reformation violence” leaves perhaps a space of vocal silence in The Ruins Lesson, as does the omission, among others, of W.G. Sebald, Paul Zanker, Kurt Schreyer or Jennifer Summit, whose “poetics of wreckage” are certainly a strong dialectical counterpoint to Stewart’s own poetical theory of ruins.

The See-Saw by Hubert Robert, c. 1786. Harvard Museums

Yet it is almost impossible to rest for long on any criticism of such an extraordinary book, of such an undeniably and unfailingly engrossing, formidably complex essay on art, permanence and impermanence, meaning and agencies of meaningfulness, pastness and the question of whom it belongs to. In fact, Stewart has a near-perfect conclusion or open ending to her breathtaking journey (to her lavishly rich and masterful ‘lesson’) around ruins, and that is Shelley’s Ozymandias. Bringing her own story to a close, Shelley’s poem, its multiple layers, subsumed perspectives and intertextual translucence, becomes a way to perhaps tacitly suggest that any individual poem, or work of art in any form, is a fragment of a larger, ever growing whole, namely the human creative imagination, critically embodied in the particulars, transcendental in its purpose and necessity. Ozymandias reminds us perhaps that ruins need bodies, places and memories to belong to, they need, in Stewart’s words, “a name and a knowing witness”. It is a plea that perhaps Constantine Cavafy heard more clearly, more evocatively, than most.

The Ruins Lesson is an electrifying engagement with the question of what is the past, what do we do with it, who created it and who should remember it, and how. These are questions that can even extend to our fascination with ephemerality, quick turnaround and consumerability for Stewart: “why, for example, do we pursue novelty at the expense of sustainability”, strewing the ‘ruins’ of our everyday lives so liberally around us?

A young (Italian?) couple in Hubert Robert’s The See-Saw shows great heuristic talents in conjuring up a playground out of a pile of ruins, next to a sublimely ironising stele with the inscription “qui se exaltat, humiliabitur, et qui se humiliat, exaltabitur”, that anachronically projects Luke, 14:11 onto a pre-Christian, pagan world and, in timely fashion, onto the future. “Whoever exalts himself shall be humbled, and whoever humbles himself shall be exalted” is certainly something one should bear in mind when looking at or thinking of ruins, certainly perhaps in the context of what Stewart calls “the unfinished”: “Companion of the ruin, the unfinished is not the sign of a damaged form, but the sign of a damaged intention… The non finito could be viewed as ever emerging, moving not toward closure, but toward, as Leopardi would suggest so eloquently, the infinito.” The ruins lesson par excellence?

Susan Stewart is the Avalon Foundation University Professor in the Humanities and director of the Society of Fellows in the Liberal Arts at Princeton University. A former MacArthur fellow, she is the author of five earlier critical studies, including Poetry and the Fate of the Senses (2002), winner of the Christian Gauss award of the Phi Beta Kappa Society and the Truman Capote Award. She is also the author of five books of poems, most recently Red Rover (2008) and Columbarium (2003), winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award. The Ruins Lesson is published by the University of Chicago Press.

Susan Stewart is the Avalon Foundation University Professor in the Humanities and director of the Society of Fellows in the Liberal Arts at Princeton University. A former MacArthur fellow, she is the author of five earlier critical studies, including Poetry and the Fate of the Senses (2002), winner of the Christian Gauss award of the Phi Beta Kappa Society and the Truman Capote Award. She is also the author of five books of poems, most recently Red Rover (2008) and Columbarium (2003), winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award. The Ruins Lesson is published by the University of Chicago Press.

Read more

princeton.edu/susan-stewart

@UChicagoPress

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.

bookanista.com/author/mika/