Rosa Rankin-Gee: Planet Thanet

by Mark ReynoldsRosa Rankin-Gee’s widely acclaimed second novel Dreamland is a thrilling and tender portrait of a disenfranchised community in a near-future Margate ravaged by climate change and economic collapse. With the seaside town’s now-defunct amusement park as a backdrop, she deftly tackles the political and personal landscape of financial disparity, poor housing, extremism, the climate crisis and the perils of leaving social issues to the whims of the free market. Sixteen-year-old narrator Chance has to grow up fast in this crumbling bolthole, isolated from what remains of functioning society, as she battles to protect her big brother JD and her mother Jas from violent criminals and the oblivion of cheap booze and suspect chemical highs. But the first focus of her care has to be the baby of the family, a boy named Blue. When a populist leader sells a sketchy dream of a fresh start away from the surrounding devastation, the town grows emptier still. But Chance is conflicted. She’s fallen in love with enigmatic outsider Francesca (a.k.a.Franky), but uncertain where that may lead. Then when circumstances finally dictate it’s time to go, the opportunity is snatched away from her – but perhaps not from baby Blue…

Mark: Can you say a few words about how the elements, themes and locations in Dreamland came together, and how Chance came into view as the main protagonist and narrator.

Rosa: A book takes a long time! Or it does for me anyway. You have to be interested in – close to obsessed with – so many different elements of the world and story to get through the marathon of it. Place was, as it often is for me, the starting point. Margate, past and present, weird and hard and beautiful, emblematic of the tidal high-and-low nature of the British seaside. I knew I wanted to write that. I knew I wanted it to be in the close future, I knew I wanted to write a love story between two young women, and really try and pin down in words the extraordinary, blinding power of that. The abject horror of current political leaders, and the way the class system affects every element of life in Britain – I want to write socially realistic novels, so those things can’t be avoided.

Chance changed as the novel did, but there were always lines or moments or bits of dialogue where I’d think ‘that’s her’, and that allowed me to find her again when at first I lost her. I love Chance.

Was anger at government policy a major spark for the novel, or was it more a case of imagining how a familiar landscape might come to be known by future generations?

A combination of both – we are simultaneously experiencing a housing crisis and a climate crisis. In this country, they haven’t come close to peaking – or clashing together – in full force yet, but they will, and it will be devastating.

According to your research, how far into the future is the Kent coast predicted to be flooded to the extent depicted in Dreamland?

According to your research, how far into the future is the Kent coast predicted to be flooded to the extent depicted in Dreamland?

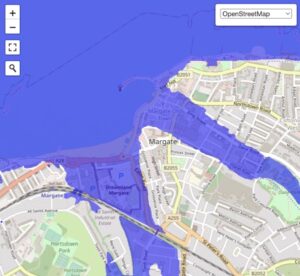

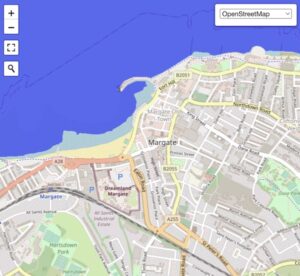

Pessimistic forecasts put 2037, which is where the main part of the story takes place, at 2 ft+, but it’s not linear or predictable. There are lots of terrifying potential tipping points. Steady declines, and then cliff-edges.

There’s an amazing/harrowing website called Flood Map which plots sea level rise. Here’s Margate from now to 10 metres (above – click on right-hand image to enlarge). To be clear, sea levels don’t have to rise permanently to this point for extreme tides and weather to produce similar effects. What’s interesting is that Dreamland is one of the first places to flood – that only requires a metre.

Over seven years elapsed between your debut novel and Dreamland. What else have you been up to?

A very rude question! No, a fair one. Dreamland was incredibly hard to get right, and took a long, long time to break down and rebuild when I first got it wrong. What else did I do? Life. You fall in love. You move countries, homes. You try to earn money. I also started my third novel in the middle, in a despondent ‘I can’t do it’ Dreamland break, which I’m back with again now. (The novel, not the despondency… yet.)

We are simultaneously experiencing a housing crisis and a climate crisis. In this country, they haven’t come close to peaking – or clashing together – in full force yet, but they will, and it will be devastating.”

How much time in a typical week or month do you manage to devote to fiction writing?

I’m happiest and most comfortable in my skin when I’m writing every day, not because the writing is burning to come out of me, or any of those clichés, which I can find pressure-filled and unhelpful. It’s more that when I’m writing, there is less of a gap between what I say I am and what I want to be – a writer – and the reality of life, which is so frequently admin and emails and trips to TK Maxx to buy a new sports bra. And happy, because I do love fiction, I love it in those rare moments where it just glides and works and you think, this is so cool and so fun, I get to play.

Your mum, Maggie Gee, has written on similar themes, most recently in The Red Children. Is there any kind of rivalry between the two of you about who gets to tell speculative stories set on the Kent coast?

Duels to the death, weekly, in the garden. Adjudicated by my father, of course, who we both try to bribe. No – not competitive at all, just interested in similar things, though done differently I think. She’s definitely the OG speculative writer – her exceptional novel The Ice People, set in a close-future Britain where climate change has sparked a new ice age, came out in 1998 – and she moved to Thanet before I did. Come to think of it, I better get my defence lawyers ready.

I see that Scribner are putting out a new edition of The Last Kings of Sark, with a cover design echoing Dreamland. Will you be back on the promotion trail with its release?

I see that Scribner are putting out a new edition of The Last Kings of Sark, with a cover design echoing Dreamland. Will you be back on the promotion trail with its release?

It’s nearly the ten-year anniversary of The Last Kings of Sark first coming out, and I couldn’t be happier to see it have a second life, with a beautiful new cover. Shout out to Scribner, but also Jack Flag who’s a phenomenal book designer. I don’t think there’s a promotion trail as such, but I also wrote the introduction to a beautiful Manderley Press reissue of Jerrard Tickell’s 1951 novel Appointment with Venus, also set on Sark and coming out in July, so there will be some fun things in the pipeline for that. In fact, anyone free on 14 July, we’re having a launch at the Cinema Museum with a film screening and drinks of course – if you’re reading this, you’re welcome.

You lived in Paris for a fair while, where you were supported by winning Shakespeare & Company’s inaugural Paris Literary Prize. How much do you miss Paris life, and how often do you tend to go back (pandemic permitting)?

I lived in Paris for the main part of my twenties, and I rarely left because I couldn’t afford to. It means that very formative part of my life is almost parked there, if that makes sense, like it waits for me when I go back, which can be haunting.

Paris doesn’t change. Which means, it relation to its static-ness, you see how you yourself have changed. I torment myself with this. What would those versions of me in my twenties think about me now? Things like that. It is a wonderful place to live and write. I’m not sure if I would have become a writer if I’d stayed in London. It is, surprisingly to some, a lot more affordable than London. You can walk everywhere. You can take a bottle of wine to the river and feel like a king. You will live somewhere the size of a postage stamp, you may have a bath in your kitchen, but you can piece together a life there with not a lot. I made some of the best friends of my life there, and I go back when I can.

Which books have you most recently read that you particularly recommend?

Speaking of Paris, my friend Ed Chisholm just published a memoir I enjoyed a huge amount called A Waiter in Paris, based on his… you guessed it… time as a waiter in Paris. It has all the pace of a thriller, but also these incredibly beautiful portraits of a place in time: Paris early morning, Paris late at night. And real Paris. Apart from that, I’ve been on a bit of a Doris Lessing bent. Also My Phantoms by Gwendoline Riley was another recent knockout. It’s eye-wateringly sharp. She pins down characters like butterflies on a spreading board.

What are you writing next?

It’s a contemporary novel, about a gay man and gay woman who fall in love, but it’s also – in a prequel-esque way – within the Dreamland universe. I’m having a lot of fun with it.

2050 is touted as the deadline for the world to go carbon neutral and preserve natural habitats. How optimistic are you that we’ll make it?

My girlfriend’s the one to speak to about that. She’s a diplomatic advisor to the Marshall Islands, low-lying islands in the Pacific which are an average of 6ft above current sea levels. She says, and for what it’s worth, I entirely agree with her: “We have to stay optimistic. Failure is not an option, because mass devastation is the alternative. Those on the frontlines of climate crisis fight in every forum for this. Ultimately we can’t let interests of a few cause destruction for so many.” You have to hope, and you have to fight.

Rosa Rankin-Gee’s first novel, The Last Kings of Sark, won Shakespeare & Company’s Paris Literary Prize. Her writing has appeared in publications including Esquire, Vogue, the Guardian, The New Yorker, The Paris Review Daily, MacGuffin, The Happy Reader and Harper’s Bazaar. She lives between Ramsgate and South London. Dreamland is now in paperback from Scribner, and is also available in eBook and audio download.

Rosa Rankin-Gee’s first novel, The Last Kings of Sark, won Shakespeare & Company’s Paris Literary Prize. Her writing has appeared in publications including Esquire, Vogue, the Guardian, The New Yorker, The Paris Review Daily, MacGuffin, The Happy Reader and Harper’s Bazaar. She lives between Ramsgate and South London. Dreamland is now in paperback from Scribner, and is also available in eBook and audio download.

Read more

rosarankingee.com

@rosarankingee

@ScribnerUK

Author portrait © Laura Stevens

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.

@bookanista

wearebookanista

bookanista.com/author/mark