Secrets and lies, red Welshmen and words of vagrant wisdom

by Mika Provata-Carlone

“A rare find. A journey through language and family, revealing lives lived on the margins and on the wrong side of history.” Rachel Seiffert

“All families develop a special language, words and references no outsider can understand. My family’s special language was Rotwelsch.” Thus begins Martin Puchner’s complex, compelling, if at times ambivalent exploration of a family and a language, or in point of fact of Language (and perhaps Family) capitalised. Of language as an institution, as a structure of survival, as a community’s foundational medium and as a repository of history or, again, as an agent of politics, ideologies, hegemonies, ideas, our very humanity and multiple identities. His impressively rich, evocative and syncretic The Language of Thieves: The Story of Rotwelsch and One Family’s Secret History, is as much a personal memoir and a work of confessional historiography as it is a chronicling of particular facets of Nazi Germany and of our current geopolitics; it is a poignant, challenging essay on belonging and displacement, on brittle margins and dominant centres; a reflection on the role of anonymous individuals or of groups existing in the shadows, and on the responsibilities of intellectuals with the power of a public voice.

Puchner is a Professor of Comparative Literature at Harvard University, and his book evinces the confidence and easy authority of someone who is both a meticulous and conscientious researcher, and an eloquent speaker and teacher. He now defines himself as a German-born American, while his voice retains the plasticity as well as the angularity of his native tongue, for all its deep and mellow East Coast accent and intonations. He has travelled far and wide both geographically and intellectually, with wonder as well as Wanderlust, a true flâneur, before settling in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which he now unequivocally calls home. The enchanted haze of an unconventional childhood filled with extraordinary figures of fascinating idiosyncrasies and formidable personalities, lures him towards a closer scrutiny of echoes and images of the past that he feels have preordained his present and his future. Former bohemianism and present scholarship merge to produce exalted rhythms of language and thought, until the vision darkens, presaging a thriller – or perhaps worse.

The Language of Thieves strikes a fine balance between a mystery story, a deeply intimate meditation and a philological history and socio-ethnological analysis. At its centre are two main threads, which will interweave into the most intricate and unsettlingly arresting patterns: a German’s inherited guilt and shame about a horrific past, and a scholar’s delight for and duty towards a much neglected, often censured or even beleaguered subject. Puchner is the grandson of a Nazi ideologue, who actively sought to produce systematic linguistic criteria for ferreting out the Jews from among the Aryans as part of Germany’s policies on racial purity; at the same time, his father was besotted with the story and the language of one of the groups that were particularly targeted by the Nazis, namely vagrants, travellers, non-assimilable foreigners. The crossover between the two strands makes for chilling reading, especially when Puchner seeks to identify beginnings and genealogies of evil.

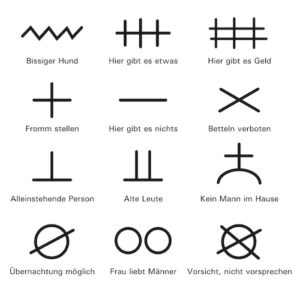

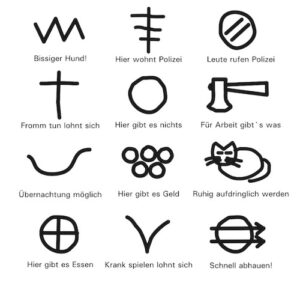

His family’s special code language included arcane signs that were not of their own making: they were zinken, scrawled hieroglyphs that had been used since the Middle Ages by vagrant groups for communicating vital information.”

How does one deal with inherited guilt? With the qualms of one’s own inert conscience and reluctance to break the complicity of silence? With the history one cannot approve, connect with or belong to? What is atonement and what is gesture politics or appropriation of a trauma, a story or a destiny? These are the key questions Puchner inevitably faces as he seeks to recover deliberately forgotten narratives, or equally calculatingly erased histories. Rotwelsch, which does not mean, as a young Puchner had playfully thought, a red Welshman, but the ‘gibberish’ of brigands and the underworld, becomes a foil, even an allegory, for engaging with the implications of History as a personal rather than a neutrally intellectual concept; for addressing questions of what constitutes identity and belonging; for anatomising our perceptions of and agency in our own fate and that of others. For most of what is an intensely suspenseful journey, this strategy of parallel visions results in sharp and piercing clarity; occasionally, the foil becomes a foible, a subterfuge for the repression or even sublimation of the critical questions and issues involved.

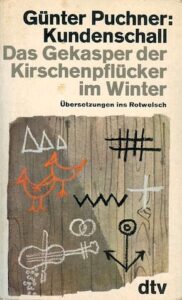

Puchner’s uncle’s book on Rotwelsch

Puchner’s story begins with a childhood game and a bafflement. His family’s special code language also included arcane signs that were not of their own making: they were zinken, scrawled hieroglyphs that had been used since the Middle Ages by vagrant groups for communicating vital information, and were still much favoured by mysterious figures who would appear at his childhood doorstep.

A fascination with the visual and verbal sociolect of Rotwelsch, with the ethnology and particular way of life of its speakers, leads to a harsher revelation. Puchner’s grandfather Karl had been a historiographer of names with a particular interest in what he called the “Jewification” of Germany. He had produced a study of the etymology, genealogy and topographical distribution of family names in order to provide “policy recommendations” in line with the Nuremberg Laws and with the Federal Agency of Genealogy, whose magnum opus had been “an alphabetical registry with an estimated 800 million card entries.” This, in conjunction with multiple independent archives and local records, aspired to effect a final, national, systematic cleansing. Puchner does not comment on this, but so natural did this process seem to Germans at the time that Jews themselves would use the same model to proudly compile Jewish community phonebooks, recording and publicising their place, presence and economic and cultural contribution to German society. A famous such phonebook was produced for Berlin, tragically and unwittingly providing the SA and the SS with the perfect extermination roadmap they needed.

The Nazis were in fact relative latecomers to the manhunt. Martin Luther had been there before them, and Puchner’s account of Luther’s shift from admirer of the Jews as the “forerunners of Christianity” to recalcitrant theorist of xenophobia, Judenfeindlichkeit and racial and linguistic purism is particularly detailed and ardent. In 1528, Luther would personally oversee the republication of the anonymous Liber Vagatorum, a book that claimed to inventory, categorise and provide the necessary glossaries for no less than 28 kinds of vagrants, vagabonds and other such shady groups. In his introduction, Luther is “one of the first to name this mysterious language” which he calls Rotwelsch, and which he attributes directly to Jews. Most of the members of these 28 groups were Christians, yet Luther would focus instead on delivering a vitriolic diatribe against Jews, foreigners and beggars, as well as (and perhaps these were the worst of all, in his view) mendicant monastic orders, all intertwined and interchangeable. A harsher, more brutal and equivocal picture of the Protestant rebellion against Rome emerges from Puchner’s analysis than the one conventionally promoted by advocates of the more benign and secular construct of Humanism. And Luther, as well as the Peace of Westphalia, which concluded the bloody Thirty Years War and which “established the modern political order in which we still live today”, emerge in Puchner’s scheme as the originary causes for the policies and attitudes of othering, foreignising and outright persecution that would follow.

In seeking to diagnose both roots and symptoms in what aspires to be a complex reflection and problematising on racism, discrimination, institutional violence against marginalised groups, evil not so pure and certainly not simple, Puchner must deal with Germany’s own reckoning with events and a past to which he relates from a position thrice removed. He is not son but grandson to the generation that was responsible. He must also assess and weigh the substantive value of what came after, and this he now seeks to examine and contextualise as a newly (or not so newly) minted US citizen. In Germany denazification was tried and abandoned, not only by the Allies, but also by the Germans themselves; memory was repressed and silenced, history was objectified, scientifically categorised, personally neutralised. As W.G. Sebald so critically commented, for Germans facing the aftershock of defeat, razed urban landscapes became almost a creative opportunity to redefine themselves, a tabula rasa on which to envision and erect a new Germany. Puchner’s generation was schooled to “reckon”: through intensive history lessons on the Holocaust and “our country’s misdeeds”, visits to concentration camps, compulsory viewings of films by Leni Riefenstahl and of footage of the mass rallies of Adolf Hitler. The examination of German guilt was thorough and forensic, but also clinical and sterilised, detached, impersonalised – “a state-sanctioned system”, rather than a success story of critical education. “We just didn’t know how to respond to something that was unthinkable and absurd.” And they did not think of asking questions to parents, grandparents, fellow Germans as to what they themselves did during the war. There were few or no leftover monuments to trigger either action or reaction. “If there was silence, I was complicit in it, helping this secret to be passed down from one generation to the next” – unquestioned and unconfronted.

The human tableau that emerges from Puchner’s engagement with Yiddish and the effect it had on Rotwelsch, with people for whom borders do not or cannot exist, is as riveting as it is – and often – harrowing.”

The Language of Thieves is, as a result, driven by what Puchner calls a “moral imperative [of] knowing history”, and this is a quality that transfuses the text throughout, whatever its wobbles and occasional relapses, into an atemporalising and depersonalising of history, agency and experience. The human tableau that emerges from Puchner’s engagement with Yiddish and the effect it had on Rotwelsch, with people for whom borders do not or cannot exist, is as riveting as it is – and often – harrowing. We learn of fear and resilience, of methodised exclusion and persecution, of solidarity but also of a certain elemental hardness. Rotwelsch families would beat their children until they only spoke in Rotwelsch, we are told, and they were poets of language as well as being rather resourceful, at times ruthlessly effective rogues. It is an entrancing, robust exploration of collective experience as formed and defined by language, of language as a definer of identity and as a structure and strategy of survival.

Rotwelsch aroused the interest not only of Luther, but also of Kafka and Goethe; it would intrigue Judah Loew ben Bezalel, a sixteenth-century rabbi and Kabbalah scholar, and his near contemporary the Orientalist and mathematician Daniel Schwenter, who would write a treatise on cryptography which he called Steganographia, or hermetic writing. It would inspire Kafka’s contemporary Gustav Meyrink, author of The Golem, and it would irk and infuriate Adolf Hitler, who would use one of its words in Mein Kampf to designate all that was verbally or conceptually abhorrent. Gregor Gog would found the Brotherhood of Tramps, as well as a journal dedicated to its speakers called The Vagrant, giving it for the first time an authentic, unmediated voice and self-identity; Charlie Chaplin would immortalise glimpses of Rotwelsch existence in The Tramp, and Bertolt Brecht certainly had the language and its people at the back of his mind. One could add the Dadas, Samuel Beckett, Marguerite Duras, Nathalie Sarraute – the French embedment of the seemingly incomprehensible and absurd into literary culture. There is a unique document by Ferdinand Baumhauer, perhaps the only genuine written record of Rotwelsch by an authentic speaker. Puchner’s analysis of how languages, idioms, idiolects and sociolects resist and survive through purposely created literary texts, what are no less than vicious attempts at their extermination, makes for thrilling reading. Yiddish triumphed against such assaults on its very essence and existence through determined use as an oral, but above all as a literary language. Puchner might have added that Marc Chagall’s wife Bella wrote two extraordinary memoirs in Yiddish, as a way of making sure her daughters would feel it as the most inalienable part of who they were. Marc would illustrate them, thus sealing that covenant between word and sign, and a father-and-daughter translation into French would affirm the ecumenical transcendence of a community’s tradition. Puchner’s uncle would make it his life project to translate into Rotwelsch a synoptic Bible of his own making, so that readers could intuit the meaning thanks to their prior knowledge of the passages. He would also translate Shakespeare, Goethe, Cervantes, seeking to build a material corpus, an incontestable presence, a linguistic permanence through art, and perhaps in this case undisguised artifice.

For the most, and for the best part, The Language of Thieves is scholarship at its most intimate and deeply personal. The hybridisation and crossover between confessional memoir and academic treatise is not always easy or unproblematic, yet one cannot give up shadowing the tensions and the tractions: one needs to know what came before, how it all ends, or, as Puchner stresses, how it begins anew. It is also a struggle between guilt (for Puchner, it is guilt by genetic association), and the affirmation of the right to speak of, or perhaps for, a particular history, a claim to both objectivity and impartiality. A visit to Sachsenhausen, where family lore claimed his maternal great-grandfather had been taken as a political prisoner (he had been sent instead to Coswig, a significantly lesser underworld), proves a stark encounter with memory, personal as well as historical: what does one do with monuments of atrocity, inhumanity, cruelty? For Puchner, the pulling down of Nazi landmarks, the razing of buildings, especially concentration camps, means that a skeleton remembrance would almost catastrophically replace the substantial evidence of a reality of horror and trauma one must not ever forget.

Vestiges of a tainted past do not necessarily serve to glorify or impose select versions of historical experience: they are also there to make that historical experience into empathy, into constructive confrontation, into an essential encounter with both guilt and trauma, if we allow ourselves the critical integrity and acuity. In Sachsenhausen, the brutal repurposing of a single, otherwise banal object, a stone water trough, serves as an unforgettable sign (or zinke), to memory and to conscience, of all that happened there. Meant to be used for washing potatoes, it served also as the place where one of the guards used to occasionally drown inmates. For Puchner the question is a current and pressing one. In a 2020 interview with The Harvard Gazette, the diachronicity of the dilemma (and the dangers of impulsive action) are for him explicit: “I think about what’s happening right now, with the changing of street names, and the tearing down of monuments and statues. Suddenly German history seems to resonate in a strange way with both our national reckoning and the fear of fascism… Tearing down statues is not enough. Your own identity in all of that has to be on the line as well.”

The vagrant life and narrative so demonised by the Nazis would become in many cases the national story for soldiers returning from the Eastern Front, for political prisoners, for an entire country now displaced.”

As Puchner seeks to trace paths, retrieve stories, animate people and their lives, anatomise a history of both humanity and inhumanity, it becomes clear that there are no linear narratives. The vagrant life and narrative so demonised by the Nazis would become in many cases the national story for soldiers returning from the Eastern Front, for political prisoners, for an entire country now displaced from a past it had to both disown and own up to. Perversely, the term “fellow traveller” would be used to expiate those whose role in the Nazi mechanism could be deemed subsidiary, or made to seem ancillary. In the case of Puchner’s father, this constant implication, interference and cross-section of stories of being and belonging would find expression in an album he created with photographs and poems on the events in Prague in 1968. It was, Puchner says, a “way of coming to terms with the past” through a transposition of paradigms, perhaps also of guilt and of experience, allowing for a neutralised objectivity or distance. The last thing he read before he died, we are told, were Nelly Sachs’ poems, an almost impossibly staggering life-image. His aim was to counter erasure with global resonance, to emulate the aspirations of Esperanto, this time building not on a construct, but on a real language. A “world literature” following Goethe, who in fact coined the term.

The conclusion of The Language of Thieves and the culmination of the reconstruction of family history but also of the history of Rotwelsch, brings Puchner to an almost frontal collision with all that he is: the scholarly recovery, preservation and ordering of the past and its trail runs through his own genealogy, starting with his father and uncle and their Rotwelsch project. His grandfather, who would resume his role as state archivist after the war, compiled a meticulous file on his own work and life; his great-uncle, also an archivist, would become no less than the director of the Nuremberg archive. For Puchner, this puts into question his own academic motives and allegiances, his integrity, even his appropriating, proprietary or intellectual agency: “what business did a former Nazi sympathiser have overseeing the records of the German past?” It is an eerie question, as eerie as the answer: “I was ashamed that my campaign against silence had now, finally, encountered a silence it was not willing to break: my own.”

The densely woven tapestry that Puchner has crafted on the question of memory, Nazi history and guilt (any historical guilt), Judenfeindlichkeit, marginalisation and domination, languages, and Language, Rotwelsch and life, unravels at this point. Multiple current academic or social debates vie for primacy and not always evident relevance, diluting the clarity of focus and subsuming several crucial aspects of the issues that Puchner has been seeking to valorise and negotiate. A major failing throughout the book has been the lack of distinction between the Rotwelsch universe and mode of life (or the more modern sociolects Puchner now aligns to it, such as urban argots, or the jargon of various trade or social groups), and the culture and history created, sustained and expressed by Yiddish or other comparable languages that arise not merely as shared codes, but as the articulation of evolving communities and living traditions. Language is more than a matrix of lives, or a universal conveyor of messages, it is an ineffable, but materially tangible space and state of belonging, of agency, continuity, creation of meaning and renewal of connections, it is a repository of memory and an enactor of visions for the future. It contains both decay and promise, it is a palimpsest of lives, of states of being and of the mind. It is this particular aspect that perhaps marks out Yiddish, or the local idiolects created by the various people living in communities under duress or isolation. Mountain or island communities, remote villages across Europe (since Europe is Puchner’s fieldwork locus), and immigrant sub-societies share an extraordinary tradition of diversification and individuation from a common root, whose beauty finds voice in dances, stories, lore and songs, in idiosyncratic expressions, in unique words or even thoughts. In Puchner’s account at least, Rotwelsch emerges as the ultimate non-community (he calls it, not unproblematically, “more Welsch than Yiddish: the Yiddish of Yiddish”); it is almost a linguistic trait that simply associates, but does not create societies. This is a quality he tacitly appreciates: a “linguistic diversity as a form of biodiversity… [languages] no longer created by humans, like paintings… but by nature, which also made them part of an ecosystem.”

Against the background of the historical narrative Puchner has been exploring, self-analysing, trying to come to conceptual and personal terms with, this biologising of language conjures up spectres of a particular kind, a geneticist version of human thought, intelligence and the social and creative imagination that has in it fearsomely more darkness than light. The eugenicist slant is pressed further, almost in apparent contradiction: “the theory that languages are tools used for particular purposes… means that extinct languages belong neither in a museum of art, nor in a museum of natural history. Tools are meant to be surpassed by better tools. Once they are, they should be preserved in a museum of technology, of human ingenuity, of the cultural past.” Dead words must be, if not buried, then at least mummified? Puchner has embroidered his text throughout with translations of phrases or literary texts into Rotwelsch to prove his point of the vivacity of the language of thieves. Reverse translation would perhaps show the critical and treacherous lacuna of this enterprise, as would an attempt to modernise an older text, that uses what he qualifies as obsolete tools, into a version that employs the so-called advanced and better ones. Soviet bloc speech, or Orwellian New Speak, Hitlerite or other totalitarian, canned and mighty verbosity comes to mind. Language is not a mere messaging system, it is, pace all technocrats, what a poet once called, speaking of literature, “a movement of the soul”.

Interestingly, and as a testament to the intrinsic power of Puchner’s book and to his awareness that it is not only linear narratives that do not exist, but also patly closed ones, the Language of Thieves ends in rather sublime irony. It finishes off with a suggestion that the journey of a language, of a people, of our exploration of our humanity is after all an endless one, certainly an open-ended one. Puchner is given the chance to ask scholarly questions of a ‘native’ Rotwelsch speaker in Switzerland through a fellow Rotwelsch amateur. The “Yenish Chief” laughs at Puchner’s effort to systematise, analyse and conserve a language that socially and culturally does not belong to him, either historically or experientially, as though in a laboratory experiment. It is a mordant reminder, perhaps Puchner now feels, that languages do articulate human communities and their stories and experiences, rather than being phylogenetic ecosystems, and that theorisations, globalisations, or any academic (or other) objectifications can be slippery or misconceived, and at times dangerously deceptive…

Martin Puchner holds the Byron and Anita Wien Chair in Drama, English and Comparative Literature at Harvard University. He has published over a dozen books, collections and anthologies, including The Written World (Granta, 2017) and is the general editor of the six-volume Norton Anthology of World Literature, used by students worldwide. He has written for the London Review of Books, Raritan Review, Bookforum and N+1. The Language of Thieves is published by Granta in hardback and eBook.

Martin Puchner holds the Byron and Anita Wien Chair in Drama, English and Comparative Literature at Harvard University. He has published over a dozen books, collections and anthologies, including The Written World (Granta, 2017) and is the general editor of the six-volume Norton Anthology of World Literature, used by students worldwide. He has written for the London Review of Books, Raritan Review, Bookforum and N+1. The Language of Thieves is published by Granta in hardback and eBook.

Read more

martinpuchner.com

@martin_puchner

@GrantaBooks

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.

bookanista.com/author/mika/