Siri Hustvedt unmasked

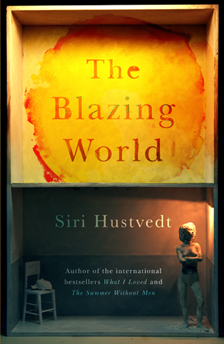

by Lucy ScholesSiri Hustvedt’s The Blazing World is a sparkling tour de force examining ideas about perception and identity. Harriet ‘Harry’ Burden, an artist railing against the New York art establishment that she believes has overlooked her work, undertakes a unique and complicated experiment: hiding behind the fronts of three male artists who exhibit her work as their own, she attempts to confront the prejudice she sees all around her. As with all convincing subterfuge, though, the boundaries between her and her ‘collaborators’ begin to break down with disturbing results. The novel, written in the aftermath of Harriet’s death, is presented as a collection of texts compiled and edited by one I.V. Hess, an academic attempting to elucidate the mystery that is Harriet Burden. Thus Hustvedt’s story unfolds through a series of extracts from a multitude of sources – Harriet’s notebooks, reviews and articles by critics and scholars, and interviews with Harriet’s children, her lover and friends – but rather than together forming a cohesive whole, with each, often conflicting, account, the mystery deepens and the possible interpretations multiply.

LS: Given the importance of disguise and concealment in the text – Harriet titles her project Maskings – it’s interesting that the novel itself is masquerading as a piece of non-fiction. What was it like to merge your two writing identities – novelist and essayist – in this one work?

SH: I wrote all the pieces inside sequentially, but I did write the introduction after, and I did the footnotes after – well, of course that’s the way one would do a book like that. But the novel, in a way, is composed as varying degrees of distance from the central story so the editor has this very straight academic tone to gloss the much hotter, almost burning tone of Harriet Burden. But since the book is really about perceptions, each voice and each position is intended to undermine every other one in a way.

My first impression of the novel was very much that it was a book about the perception of differences between the genders, but then as I read further, more and more layers were peeled away and I realised I’d only seen the tip of the iceberg.

Oh yes, in fact I think the whole novel – I hope – creates so much doubt that those divisions really get cancelled out. Harry’s supposed to be someone who in some way transcends gender, and I think it’s unusual to have a female genius at the centre of a book. The very idea of female genius is a kind of oxymoron in our culture, so Harry is meant to dance and leap and rage against every category – she’s a kind of monster. The monster theme keeps recurring; a monster is that thing that we can’t fit into a box – the study of monsters is teratology, the study of things that can’t go into all those boxes in an encyclopedia.

It’s interesting you mention fitting things inside boxes, as this seems to be an idea you’ve been interested in for a while, particularly in relation to storytelling. The first of Harriet’s three masked shows, The History of Western Art, features seven story-box crates, which in turn are reminiscent of the story boxes made by the artist Bill Wechsler in your novel What I Loved (2003), as well as the three boxed images painted by Edward Shapiro in the corner of his portraits in The Enchantment of Lily Dahl (1996), each of which he fills with a story told to him by his subjects as they sit for him. These Joseph Cornell-like boxes are clearly a form you’re drawn back to again and again, do you know why?

All the time! I seem to be obsessed with them. Now there’s a number of possibilities – one doesn’t always know, obsessions are probably the most difficult part of one’s own work to track because they appear and they feel compelling and so you go to them – but I think there are a few things. When I was quite young, in 1980, I saw a Cornell show at the Museum of Modern Art that made a huge impression on me. Actually after I saw that show I wrote a poem for Cornell that was in little boxes…

More broadly – and I’ve just been thinking about this lately – aesthetic experience, especially reading books, is something that is bounded; I mean you’re not in the world, you’re looking at a text, but the way you read the text, for most of us, is that we make pictures in our mind. In other words, when you remember a book, you’re not remembering pages, you’re remembering the characters and what they did in some way. So I think this idea of an aesthetic frame is part of the whole box business. And also, when it comes to the aesthetic, there’s a certain safety – you know when you’re reading a book you can feel all kinds of emotions, you’re having emotions, and those emotions are real but the characters are imaginary – and so you’re experiencing all this inside the safety of an aesthetic frame, and I think ever since I was a child I’ve always loved to go into that aesthetic frame, away from the hyperactivity of the sensory world.

As suggested by both your non-fiction (much of which is critical works about art and artists) and your fiction, the term ‘art’ for you seems to encompass both the written word and the visual. Can you expand on the relationship between the two and your interest in both?

Well they are all art, but I do think the word functions in a different way from the image. It’s probably older in our development – visual images come earlier than, say, learning to read or acquiring language, so there’s something older about images, and of course when you’re looking at a picture (not film, film is different) it’s there all at once, it’s not sequential. Reading is sequential, so they are different experiences but they’re both experiences with an aesthetic frame.

Your protagonists are often artists, so you become both novelist and artist as you create their works as part of your narrative. How do you go about this – do you ‘see’ the works as, say, a visual artist would, or do you think about what you want them to mean critically and then assemble them accordingly?

It’s interesting to make artworks that are words, because that’s what I’ve done. Both in What I Loved and The Blazing World there are artworks that appear, they’re described, and I guess their function in some way is clearly an interaction between the psychology of the artist and the broader world. Art is located, in a way, between the person and the world, and when someone makes art, in these cases visual art but it’s also true for literature, often the work of art knows more in some way than the person making it. I mean this in the sense that the unconscious is clearly at work in these things. So in a novel, the artworks are there in some way to tell us even more. In this book, the interaction between Harry and her masks, which becomes more complex with each artist that she uses, the works that come out of these collaborations – well, they’re not strictly collaborations, but in some way the other is affecting her – they’re coming out of that overlap, if you will, between Harry and the other.

You need to describe enough so that the reader can make a comprehensive work of art, but you can’t say too much because then you drown the reader in detail.”

It goes without saying that the three ‘mask’ exhibitions – The History of Western Art, The Suffocation Rooms and Beneath – are central to the novel. How did you approach the creation of each of them? Clearly you’re not able to show them visually to your readers, you’re limited to describing them only, but do you think of them visually?

I just see them and then I describe what I see. They’re just kind of there – that happened in What I Loved too – I don’t know how they’re there, but they are, so I just describe them. You need to describe enough so that the reader can make a comprehensive work of art, but you can’t say too much because then you drown the reader in detail. It’s a real balance. I think that’s where the other part of writing, editing – what I call combing – comes in. You have to keep combing your pages, getting rid of extra hair as it were.

I just see them and then I describe what I see. They’re just kind of there – that happened in What I Loved too – I don’t know how they’re there, but they are, so I just describe them. You need to describe enough so that the reader can make a comprehensive work of art, but you can’t say too much because then you drown the reader in detail. It’s a real balance. I think that’s where the other part of writing, editing – what I call combing – comes in. You have to keep combing your pages, getting rid of extra hair as it were.

You’ve already mentioned that Joseph Cornell has been an important influence on your work, but which other artists were particularly important when it came to the creation of Harriet Burden and her work?

Well, Harry has a whole notebook on Louise Bourgeois. Bourgeois, in some way, is haunting the whole text, and I wanted that to be clear. Harry’s use of the metamorphs is not identical to but bears some resemblance to the stuffed human forms that Bourgeois did, so there are influences, and those influences are meant to be part of the text and part of Harry’s work. And, of course, my fictional universes and the actual art world come together in that I have Harry like Bill Wechsler’s work.

The Blazing World is a theoretically dense novel. This, of course, stems in part from the fact it takes the form of non-fiction, as for it to be convincing the critical essays demand footnotes and Harriet’s own notebook entries necessarily have to be academic, but are you dealing with theoretical concepts that are important to you? Are you using the novel to work through theories you’re interested in?

The greatest genre for ideas is the novel. The novel has a teleology of story but you don’t have to decide, it’s not an argument, however it can contain arguments. The conflict, or the polyphony – a word I use in The Blazing World – that results is a fantastic form for the interaction of ideas inside a single text.

Part of the fairly complicated feminist aspect of the book is Harry’s notion of what the human mind is and her position is very much one I share: that we are embodied creatures and the mental cannot be separated from our neurophysiology, but also not from the world in which we live – the body is not taken out of its environment – all of this is part of her thinking. Rune [the male artist who provides the front for Harry’s final exhibition, Beneath] on the other hand, is interested in computational theory of the mind, which is a completely different thing. It’s not about embodiment; it’s about the mind as a kind of computer. The fantasy that Harry’s criticising, that Rune is deeply involved in, and, of course, as a result of which, comes to a tragic Frankenstinian end, is this idea of artificial intelligence and that at some point human beings will be, in a way, consumed by a machine intelligence that’s greater than they are. To some people this sounds kind of idiotic, but there is in fact a huge amount of serious scholarship devoted to these ideas. I think they are fantasies – part of the fantasy is the desire to evade the female body altogether; it’s birth from the head, in other words, if this machine fantasy comes to be then of course there’s no need for women or babies or giving birth.

There are traces of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein – the original text that deals with the notion of non-biological birth – throughout The Blazing World, most often in connection to Harry herself. In one of her testimonials, her friend Rachel Briefman says the character Harry most identified with is the monster.

She does! It’s very complex. It’s not, Harry says at some point, “either, or”, and of course “either, or” is also a reference to Kierkegaard. This is a deeply Kierkegaardian text, there’s irony upon irony upon irony – just what you identified here, you can’t split this. Harry herself identifies hugely with the monster who, well, was born from a scientist. For Mary Shelley this was an exploration of her deep inner life. It’s quite a book. I re-read it not so long before I started The Blazing World and the monster is the most amazing creature: enormous, touching and horrible. I quite intentionally meant Harry to have that identification, and for her to have a certain monstrous aspect. And of course she’s making all these things. At one point Bruno [Harry’s lover] talks about how she never stops working, she might be full of this anxiety about lack of recognition but she never stops working, and he says something like “she popped one work after another out of her like wet, bloody newborns”, so the birth thing runs through the novel.

I think one of the reasons that women making art has been so complicated has to do with the fact that female creativity is supposed to be limited to babies. And then, because that’s something that men cannot do, there’s the idea that artistic creativity is a male function. When women do it there’s a kind of resistance.

The novel obviously goes beyond ideas of just gender difference, but would you describe it as something of a feminist manifesto? Do you see the sexism that it’s dealing with as ingrained?

There’s no question that the sociology, if you will, is accurate, I mean when was the last time you heard a male artist described as a ‘man artist’? It’s what Simone de Beauvoir identified a long time ago in The Second Sex, the problem that men stand for the universal, and that hasn’t really changed. So in that way all the sociology is accurate; the problem here is that Harry is also involved in her own self-sabotage so it’s psychologically a very complex issue. Hess the editor points out very early on that Harriet leaves the art world; she just stops trying. Then inside the text the rather sensible art writer Rosemary Lerner points out that Harry wasn’t quite as dismissed as she thought, it’s part of her fantasy and related to her own father and her first marriage. All of this psychological stuff is part of Harry’s perception of the world, which is not necessarily more perspicacious than any of the other characters’; her views are always modified by somebody else. But that there’s a kind of fear of women in some of the narratives is very clear. The book is a feminist book but it cannot be reduced to a feminist parable.

Harriet’s daughter Maisie Lord goes some way to describe the complexity of her mother’s identity. She describes her as a woman, not of multiple personalities but of many “protean artist selves, selves that popped out and needed bodies”.

Yes, but the whole book is a kind of multiple-personality book!

Yes, through the conflicting stories told it forces you to continually see Harriet anew, and then just when you think you’ve got a handle on her, you throw in the suggestion that she might have fictionalised her notebook entries, leaving behind her “a novel of sorts”.

What you have here is almost like a parable of fiction itself.

This complex layering of personas and personalities made me think again of the story boxes. Harriet’s diaries become another potential framed receptacle for a story or stories.

If there’s any kind of climax to all this it’s when Harry does that crazy thing and writes as Richard Brickman [an art critic who writes a piece about Harriet Burden’s work]. I had a wonderful time doing it, but you realise too that this is so destabilising that Hess, who’s been trying to untangle what’s irony and what’s parody, at this point doesn’t know what to do anymore.

The reader is intended to become part of the drama of the book itself, which then generates more interpretation. For this reason I’ve had a kind of funny distance from reviews.”

There’s that great description of Brickman as “another character in the larger artwork, another mask, this time textual”. With every additional persona, and every additional analysis, the scope of Harry’s project becomes bigger. As one character puts it: “It wasn’t merely a sleight-of-hand trick; the magic had to unfold slowly and eventually be turned into a fable that could be told and retold in the name of higher purpose.” It seems to me that the boundaries between the novel and the story it contains are slowly broken down in exactly the same way as those between individuals and their identities. In this way the novel itself, made up of its various texts, becomes part of Harry’s project too. It’s part of this “larger artwork”.

I did actually begin to think of the reviews of my novel as in some way proliferations of Harry’s project.

So the reader’s interpretation is part of the process?

Exactly. The reader is intended to become part of the drama of the book itself, which then generates more interpretation. For this reason I’ve had a kind of funny distance from reviews, even with negative reviews [of which there haven’t been many] I’d find myself in an analytical rather than a personal position. I’d read it as the reviewer allying him or herself with a certain character.

Actually. I have to shut myself down on this book now because for me it became a hugely generative project – I came upon a form that just doesn’t quit in some way, so you have you walk away.

But you’re encouraging the reader to embrace this ambiguity?

Yes, and enjoy the dance, to take pleasure in the dance, and the levels of wit.

I think of it as something of an interpretative game. I enjoyed being part of the puzzle.

It is a puzzle and a game, yes, but it’s a very deep puzzle that has no resolution, and it’s a game that has a dark side. It’s one of the few novels to pit a man and a woman against each other in an Agonistic battle for power. This doesn’t happen very much.

Siri Hustvedt is the author if six novels, a poetry collection and four books of essays. Born in Minnesota, she now lives in Brooklyn. She has a PhD in English from Columbia University and in 2012 was awarded the International Gabarron Prize for Thought and Humanities. The Blazing World is published by Sceptre in hardback, eBook and downloadable audio. Read more.

sirihustvedt.net

Lucy Scholes is contributing editor at Bookanista and a literary critic and book reviewer for publications including the Daily Beast, the Independent, the Observer, BBC Culture and the TLS. She also teaches courses at Tate Modern and Tate Britain.

Follow Lucy on Twitter: @LucyScholes