Stage dive

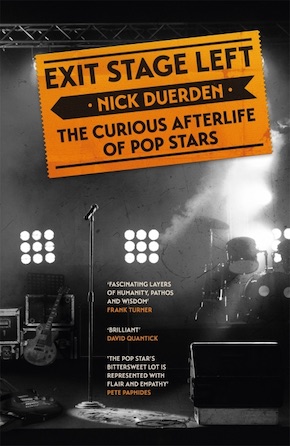

by Brett Marie“The troubadour’s spirit is to not chase anything. You simply go about your business and wait for the world to spin slowly on its axis until eventually it comes back around and finds you – still there, waiting patiently,” writes journalist Nick Duerden in his new book Exit Stage Left: The Curious Afterlife of Pop Stars. It’s a beautiful thought. But wait, that can’t be right. Can it?

Rock ‘n’ roll music’s first poet laureate Chuck Berry created the template for pop stardom with his best-known song, ‘Johnny B. Goode’. Across three breathless verses, Berry shouts the story of a young guitar hotshot from “deep down in Lou’siana close to New Orleans,” who, his mother promises, will someday “be the leader of a big ol’ band”. Berry’s exuberant delivery is infectious, and his switch from third-person storytelling to second-person testifying in the final verse turns his fictional character’s one-in-a-million rise to fame from a one-off fairy tale into a universal directive aimed squarely at his listener. The song’s message has reverberated for decades; if there’s a player out there who didn’t hear echoes of Mrs Goode’s prophecy as they bashed out their first sloppy guitar riff (“Maybe someday your name’ll be in lights…”), I haven’t met them.

Reflecting on the song’s success in his 1987 autobiography, Berry claims to have modeled ‘Johnny’ more or less on himself, with a couple of crucial changes, notably slotting his character’s log-cabin origin story in place of his own more middle-class upbringing. This taste for extremes works in both directions. Bruce Springsteen’s ‘Johnny Bye-Bye’ acts as a sequel of sorts to Berry’s anthem, lamenting the loss of the archetypal rags-to-riches figure Elvis Presley. Tellingly, Springsteen was compelled to write such a song only after Presley’s tragic passing. Just as, in Berry’s words, “a story that brings a subject from out of the boondocks to fame and fortune is more dramatic than one out of midtown to somewhere crosstown,” Springsteen found Elvis far more interesting post-mortem than he did during the final half-decade which the King spent alive but musically irrelevant.

Like the songs they contribute to our life soundtracks, the biographies of pop musicians tend to be short and sweet, favouring the dramatic, all but ignoring the unremarkable. Nick Duerden puts it bluntly in Exit Stage Left: “By rights, [pop stars] are supposed to be a flash in the pan, a pin-up who disappears before we have the chance to get bored of them, thus leaving in their wake slippery moments of throwaway bliss.” As a result, artists who stop making hits, whose lifestyles stop making headlines, are “cursorily snuffed out… replaced, with barely a pause, by the next big thing in an industry that has always fetishised the next big thing above all else.”

If this cultural mindset feels too callously forgetful, Exit Stage Left makes for a fine corrective, with Duerden taking a series of deep dives into that post-fame purgatory to which the snuffed-out legions of one-hit wonders and overage teen idols are banished. As Duerden writes in an email to me, “I wanted this book to be less about music than about the human being behind the music, so I approached artists from every genre whose stories I thought would resonate, and also reflect different experiences.”

The drop, that point at which each artist sees their fame and fortune yanked away, varies so widely in its timing and severity that it can sometimes feel utterly random, but that isn’t to say that there are no morals to these tales.”

Duerden has plenty of different experiences to offer, but they follow a broadly similar arc: a fateful single launches an act from the depths of obscurity into the public consciousness; following a set number of months in the Top-Forty stratosphere, they float (or crash) back to earth, and rejoin the faceless masses in a new kind of obscurity, in which the memory of their big hit hangs around them like a calling card – or a millstone. The drop, that point at which each artist sees their fame and fortune yanked away, varies so widely in its timing and severity that it can sometimes feel utterly random, but that isn’t to say that there are no morals to these tales. Duerden turns up innumerable factors for his artists’ eventual fade-outs. They can be too addicted (see: Peter Perrett), too timid (Del Amitri’s Justin Currie), too disinterested or disillusioned with the type of fame they’re offered (Chumbawumba, Cornershop), or simply too much (Adam Ant).

Stand and deliver: Adam Ant still doing his thing at G-Live, Guildford, in 2011. Steve Speight/Wikimedia Commons

The word Exit in the book’s title is misleading. Yes, at some point a good number of Duerden’s subjects drop their instruments and make for the wings, while others simply get the hook. But for more than one among this varied cast of characters, the music never stops, the performance never ends. Robbie Williams and Don McLean might cede their places at centre-stage, but their drive to create and perform never leaves them. “I was struck time and again by just how stoic – often stubborn, too – they were, and who didn’t want to do anything else with their lives, whatever the cost. I found it fascinating that no one could ever fully walk away from pop music. And those who do walk away, or at least want to walk away, find that their old hits essentially keep working for them, maintaining their profile on their behalf. They get played on the radio all the time, get used in films and adverts, which then prompts offers from promoters, invitations from reality TV shows, etc.” And the tug of the limelight, no matter how diminished, is quite a force. “Interestingly,” says Duerden, “several of my interviewees who had told me that they were no longer interested in doing music then promptly started doing it within months of our conversation.” Of course they did. One anecdote Duerden tells me illustrates why: “I once interviewed Miki Berenyi from the early 90s shoegazing act Lush who told me that, after the band split up, she became a subeditor at a magazine. Colleagues could never entirely accept that someone who had once been on Top of the Pops was sitting next to them in an office doing ‘ordinary’ work, and she herself found that nothing quite compares to the thrill of being on stage, singing songs, and having people scream at you. So she formed another band…”

In chapter after chapter we see the same rise and fall play out, each time with a new half-remembered name riding the wave. There is a certain superficial pleasure to getting status updates on these artists, about whom for decades we might not have given a thought, but Duerden’s empathy for his subjects keeps Exit Stage Left from ever descending into a simple game of Where Are They Now? “I wanted the book to be as empathetic as possible, and kind,” Duerden tells me, adding, “These weren’t pop stars in their full pomp anymore, they were people for whom Life, capital L, has happened.” By digging past the public stories and into those capital-L lives, the author discovered a commonality that his subjects shared – one that’s far more satisfying to read about than the endless loop of their riches-to-rags plotlines. “I found them all to be humble and thoughtful, and full of gratitude for still being able to do what they do. Even those who perhaps came across as a little curmudgeonly, angry, or bewildered, had the kind of humility to them I didn’t always see when interviewing them for music magazines back in the 1990s. They no longer took their audience for granted. They were grateful, and I wanted to convey that: pop stars are human, just like us.”

Duerden’s hopeful outlook and immense goodwill towards his subjects, elevated by his uncommonly elegant and evocative prose, combine to ensure that his gamble pays off.”

Perhaps they were grateful, but that doesn’t mean all were eager to make Duerden’s task easy. “A lot of people didn’t want to talk to me,” he tells me, “perhaps because I was asking them essentially to discuss… not failure exactly, but what it’s like to live with the presumption that perhaps your best was behind you – something all of us feel, of course, at some or other point in our lives. I suppose those who were happy to talk were in a relatively good place. Managers of several artists told me that their charges wouldn’t be able to speak quite so candidly in a public forum, and several who had agreed then had second thoughts. (One manager told me that this was a subject they had thought about a lot, ‘but he isn’t in the right headspace to discuss this right now’).”

Even absent these challenges, covering over fifty artists within 300-plus pages is an ambitious project – one that isn’t without risk. Such a smorgasbord of stories, of less than mythic characters leading less than epic lives, could easily have made for a repetitive dirge. But Duerden’s hopeful outlook and immense goodwill towards his subjects, elevated by his uncommonly elegant and evocative prose, combine to ensure that his gamble pays off. And all that repetition has an interesting side effect: reading all of these tales back-to-back, I come to recognise how pop culture’s conventions have preconditioned me. Over and over, Duerden lays out the same story. Over and over, I find myself strapped into fame’s rollercoaster with a new artist beside me, climbing to the first peak, feeling the first descent in my gut, occasionally rising and falling again. And as I feel the story’s end approaching, I await the last climb that will send the artist out on a high note of renewed fame and fortune. Despite the dozens of stories Duerden has already told me that upend this trope, I’m surprised each time my companion steps off somewhere partway up the slope, often finding – or planting – themselves in a comfortable equilibrium away from the spotlight our culture tells us is their destiny. I’m further surprised at just how relieved I am to see them reach that happy medium. The view from the penthouse sure is spectacular, but as Exit Stage Left can attest, there’s plenty of fine real estate closer to the ground.

Nick Duerden is a writer and freelance broadsheet journalist. He has written widely on the arts, family and health, and is the author of two novels, a memoir on fatherhood, and other non-fiction works. Exit Stage Left is published by Headline in hardback, eBook and audio download.

Nick Duerden is a writer and freelance broadsheet journalist. He has written widely on the arts, family and health, and is the author of two novels, a memoir on fatherhood, and other non-fiction works. Exit Stage Left is published by Headline in hardback, eBook and audio download.

Read more

nickduerden.co.uk

@Nick_Duerden

@headlinepg

Brett Marie, also known as Mat Treiber, grew up in Montreal with an American father and a British mother and currently lives in Herefordshire. His short stories and other writing have appeared in publications including The New Plains Review, The Impressment Gang, Pop Matters and Bookanista, where he is a contributing editor. His debut novel The Upsetter Blog is published by Owl Canyon Press.

Brett Marie, also known as Mat Treiber, grew up in Montreal with an American father and a British mother and currently lives in Herefordshire. His short stories and other writing have appeared in publications including The New Plains Review, The Impressment Gang, Pop Matters and Bookanista, where he is a contributing editor. His debut novel The Upsetter Blog is published by Owl Canyon Press.

Read more

@owlcanyonpress

Facebook: Brett Marie

@brettmarie1979

bookanista.com/author/brett-marie/

Author portrait © Roxanne Fontana