The horror of the self

by James Riley

In November 1979, the American current affairs programme 60 Minutes ran an item called ‘Wellness’. In it, host Dan Rather profiled the work of Dr John Travis, a former physician-turned health educator who had, in 1975, opened the Wellness Resource Center in Mill Valley, an affluent city in California’s Marin County. As Rather discovered, Travis offered clients dietary consultations, he worked with them to develop exercise routines and he used such futuristic devices as the biofeedback monitor to map out their stress triggers. A day at the Wellness Resource Center could also involve a dip in their downstairs hot tub, a positive visualisation session at the ‘Lifestyle Evolution Group’ or just some good old-fashioned group hugging out by the trees, where all the parties used to happen. Despite his medical background, Travis offered no formal diagnoses, he provided no prescriptions, the Wellness Center was not a dispensary. Instead, as Rather reported to his nationwide audience, Travis offered ‘the ultimate in self-care’. He helped his clients – many of whom were struggling with work pressures or wrestling with mid-life crises – to find out ‘why they were sick’.

‘Just because you aren’t sick, you don’t have any symptoms and you could go and get a clean bill of health, doesn’t mean that you are well,’ counselled Travis during his interview for the show. ‘It doesn’t mean that you are going to prevent disease further down the line.’ Wellness, then, was framed as ‘an ongoing, dynamic state of growth’ not merely ‘the absence of disease’. It described a holistic approach to health that combined physical fitness with mental wellbeing and the cultivation of a positive, optimistic approach to one’s sense of direction in life.

A miracle cure, surely? Rather was not entirely convinced. Towards the end of the segment, he interviewed some of Travis’s beaming clients. They were radiant with good health, positively placid with it, and seemed prepared to do nothing else than to sing Travis’s praises. Suspicious of all these good vibes and eager to prod at the consensus, Rather wondered aloud if there wasn’t something more sinister afoot in Mill Valley. Was the ‘wellness movement’ a middle class-cult? he asked. No, came the reply. ‘In wellness, you are the leader,’ explained one smiling client, ‘you’re your own guru and you’re the perfect person that is trying to make your life better and more full.’ It was an ironically evangelising response that sounded not unlike a disciple quoting from the texts of a middle-class cult.

Dan Rather may have introduced wellness as something new on television, but by 1979 cinema had already rehearsed and made explicit the covert fears feeding into his report. “

Rather’s scepticism was not just a matter of journalistic protocol. In the late seventies, particularly in America, cults and indeed any group or activity with the merest whiff of cultish behaviour were a matter of considerable public anxiety. The decade had begun in the immediate aftermath of the Manson murders of August 1969, it had seen the rise of multiple New Religious Movements, New Age belief systems and alternative health programmes, and a year prior to the 60 Minutes ‘Wellness’ broadcast, there had been the terrible reports of the mass murder-suicide at Jonestown in Guyana. On the surface, the pro-active health benefits of wellness might have seemed innocuous when compared to the likes of the Peoples Temple. However, in the febrile, paranoid days of the decade’s end its easy to see how this smiling group – dedicated to a highly specific health programme, beyond the reach of professional practice and under the care of a charismatic ex-doctor – could have appeared to be victims of benign brainwashing.

America’s viewing public was certainly primed to adopt such a view. Dan Rather may have introduced wellness as something new on television, but by 1979 cinema had already rehearsed and made explicit the covert fears feeding into his report. Across the decade, films like Shock Treatment (1973), The Terminal Man (1974) and before that, Seconds (1966), had featured mysterious companies and private clinics that promised endless self-perfection, only to have such fantasies revealed as dehumanising experiments, procedures that either through misjudgement or malign intent caused great harm to those involved. Meanwhile, drive-in fare like I Drink Your Blood (1970) and The Astrologer (1975) variously re-packaged the last vestiges of the 1960s counterculture and the new decade’s deepening interest in mysticism and the occult, to warn us of the dangers inherent in following self-styled guru figures. Such films varied widely in terms of their mood and tone. They were also a world away from the curious journalism of 60 Minutes and its magazine-style take on wellness. The throughline, however, was a shared concern with the possibility of human transformation outside the perceived limitations of conventional medical practice.

Films like I Drink Your Blood and its more gothic counterpart The Deathmaster (1972) were not the cinema of the superhuman. Their scenarios were monstrous, their plotlines were cautionary, and, on balance, their dominant generic mode was that of ‘horror’. That said, they were spiritually akin to the gentler aims of wellness. John Travis was attempting to impart practical advice on how to improve personal health and to maximise the potential of his clients, while filmmakers were elsewhere showing the shadow side: the dire consequences of scientifically, chemically, or magically changing the physical and psychic capabilities of the human.

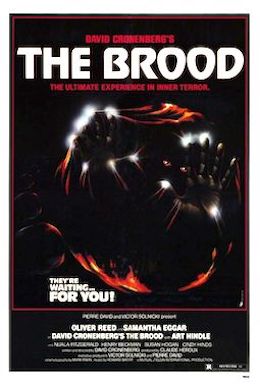

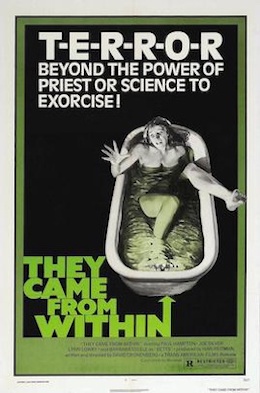

Of this group, there was no filmmaker of the period who explored these ideas with such gusto and provocation as the king of ‘body horror’: the Canadian writer-director David Cronenberg. In 1970 Cronenberg released Crimes of the Future, a follow-up to his shorter, documentary-like film of the year before, Stereo. Both took place in strange institutions and featured characters who open themselves to experiments that blur the boundary between the physical exterior and the psychic interior. His commercial debut Shivers (1975) and its follow-up Rabid (1976) developed this scenario with their focus on dangerous procedures – variously venereal, parasitic, and surgical – that go awry, first in a luxury tower block, then across an entire city. Particularly in Shivers, Cronenberg had let rip with an attack on middle-class mores, in which transgression was heaped upon transgression before the film reached its orgiastic conclusion in that cauldron of social anxieties, the swimming pool.

Cronenberg’s first salvo of features played out like an antiseptic, nightmare version of Paul Mazursky’s Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice (1969). In that film, two couples wrestle with the possibilities of partner-swapping after attending an encounter group at a thinly veiled version of California’s legendary Esalen Institute. Established in 1962, Esalen was the symbolic stronghold of the Human Potential Movement, a loose network of overlapping practices and philosophies geared towards optimising the ‘self’. Encounter groups were an essential part of the Esalen experience, along with bathing, gestalt workshops and various types of message-based ‘bodywork’. They were a form of communal therapy in which participants would attempt to establish open communication with each other and themselves. In theory, an encounter group was a safe space for the airing of one’s thoughts and feelings, but in practice they could be excoriating arenas of brutal ‘honesty’ in which oversharing as well as no-holds barred verbal attacks could be the norm. Long-held beliefs and lifestyle choices where rigorously deconstructed in these sessions before participants were sent back into the world, ready to quit their jobs, file for divorce, or in the case of Mazursky’s initially uptight middle-class characters, flirt with swinging.

For critical observers like Tom Wolfe and Christopher Lasch, Esalen was encouraging a philosophy of selfishness, in which the satisfaction of one’s own needs, physical and psychological, were paramount.”

From Esalen’s point of view, if the encounter group had helped an ‘authentic’ desire come to the surface; if you were being true to yourself in the pursuit of it, then all to the good. The Esalen creed was one in which self-care equated to self-validation. For critical observers like the writer Tom Wolfe and the sociologist Christopher Lasch, however, Esalen was encouraging a philosophy of selfishness, in which the satisfaction of one’s own needs, physical and psychological, were paramount. Lasch saw this attitude as part of a widespread ‘culture of narcissism’. Wolfe was more direct in his condemnation. Writing in New York Magazine in 1976, he dubbed the still in-progress 1970s The ‘Me’ Decade. Filmmakers like Cronenberg seemed to agree with these criticisms. His institutions, like the House of Skin in Crimes of the Future or the Canadian Academy for Erotic Enquiry in Stereo are grand fortresses of solipsism in which terrible things occur, but at the same time he invests their esoteric experiments with awesome power. Cronenberg’s films may well be horrific, but they’re often about the difficult cultivation of new, posthuman forms. Cronenberg’s human characters are not always destroyed, more often they’re transformed into something other; something for which we don’t yet have the right language to describe.

The Brood (1979) his last film of the seventies, took this idea as its central premise. Based in the Somafree Institute, another of Cronenberg’s all-too-believable fictional establishments, the film looks at the practice of ‘Psychoplasmics’. Sounding not unlike a seminar one could attend at Esalen or the Wellness Resource Center, Psychoplasmics is a therapy technique in which the expression of repressed feelings is channelled into extreme bodily transformations. Across the film welts appear on the bodies of the Somafree patients, mystery organs surface and, as implied by the title, aggressive tulpas emerge as physical manifestations of buried rage.

The Brood was released in June 1979, six months after Lasch published The Culture of Narcissism (1978) and six months before 60 Minutes broadcast their ‘Wellness’ segment. When John Travis spoke earnestly to the nation about helping people determine their own problems and thereby improve their lives, he carried no hint of Cronenbergian intensity. By that time, though, the decade’s surrounding cinematic and critical culture had built up a solid set of stereotypes when it came to experimental health. Wellness may have emerged from Esalen’s celebration of the self, but when it came to films like The Brood, confronting the self – the buried, body-disrupting self – in all its monstrous, provocative glory was a moment of ecstatic horror. This representation has persisted. Take, for example the hypnotic intensity of Panos Cosmatos’ Beyond the Black Rainbow (2010) with its Esalen clone, the Arboria Institute; or Eddie Alcazar’s delirious, mutant take on human perfection in Divinity (2023). Such images speak volumes about the general mindset of the seventies, not so much the attitudes of those offering or wanting to seek out alternative channels of therapy or wellness, but the attitudes of those looking on. Fear, scepticism, perhaps a residual conservatism wanting to keep the status quo intact? These attitudes certainly had their place in the politics of the decade. But what, John Travis may have said in response, are you all really afraid of?

—

James Riley is a Fellow of English Literature at Girton College, Cambridge, focusing on modern and contemporary literature, popular film and 1960s culture. His previous titles include The Bad Trip: Dark Omens, New Worlds and the End of the Sixties. He also makes films and performs spoken word poetry. Well Beings: How the Seventies Lost its Mind and Taught Us to Find Ourselves is published by Icon Books.

Read more

english.cam.ac.uk/people/James.Riley

@EndOfSixties

@iconbooks