The new censor

by Bothayna Al-Essa

The new censor was late to his office. He had stood too long, rooted to the ground in front of the Censorship Authority building, trying to guess the number of floors it contained. A few meters from the entrance, counting on his fingers, he was certain there were at least thirty-six floors. But the elevator only listed thirty.

He had heard a rumor about secret floors in government offices. They were reserved for the higher-ups, filled with computers, smartphones, and tablets. In these rooms, they accessed in secret what was called the Internet. But this was just a rumor, and he knew what experts said about rumors: they were the vestige of a biological instinct to invent stories, a primitive instinct from the Old World, in the process of being wiped out.

The Censorship Authority building was a gray cube, its windows squeezed too close together and overlooking the main road. To one side was a parking lot where cars could also be charged. On the other side was a garden that no one paid much attention to, a grassy patch of land bordered by bougainvillea bushes and oleander. He sighed, staring at it all, still unbelieving of his bad luck.

After long months of waiting and living on unemployment, the call had come from the employment office informing him of the book censor post. It wasn’t the job he wanted. If he was fated to work for the Censorship Authority, he would have preferred to be at the Inspection Bureau. But refusing it meant waiting for who knows how much longer, barely scraping by. He couldn’t do that to his wife, who was burned out from being the sole breadwinner.

Authority personnel in khaki pants and starched shirts took hurried steps to the entrance. The hallways teemed with employees. An aroma of coffee mingled with the acrid fumes of floor disinfectant. There was another elusive smell that wound its way through the building – maybe he was the only one who noticed. He guessed someone had forgotten to wash their socks or that a glass of water had spilled on the carpet somewhere. Something must have happened, leaving behind a chicken-coop-boiled-cabbage-damp-socks sort of smell.

Even the rabbits had arrived before him. He came across two in the hallway and tried to kick them, but they were always too quick. White devils! They defecated all over the place; he spotted at least three sets of droppings that had escaped the janitor’s broom. He imagined the rabbits were leaving behind little tokens of love, doomed souvenirs to remind mankind, forgetful by nature, that their organizations were always susceptible to penetration. He yelled at the janitor to sweep up the filth. Spewing profanities, he entered the department and sat in his chair. Instead of inspecting a book, he placed one leg atop the other and surveilled the other seven censors.

Like wooden dolls in a puppet theater, their invisible strings controlled by a faceless man, each censor would turn a page at the same time. Blink in unison. Scratch their noses at once, then suddenly start writing.”

He thought of the first day he’d arrived here for work, appointment letter in hand. I’m the new censor, he had said. They all greeted him with a nod. From the outset he noticed an inconceivable synchronization in their actions, as if they were septuplets. Aside from their work uniform, each of them wore spectacles and was balding. Like wooden dolls in a puppet theater, their invisible strings controlled by a faceless man, each censor would turn a page at the same time. Blink in unison. Scratch their noses at once. Stretch out their hands to reach for a pen, then suddenly start writing, completely in sync. They would pick up their reporting notebooks and record violations from each title. Sometimes one of them would sneeze and the rhythm that linked them would be broken. He asked himself if he too would one day be part of this collective harmony, part of the whole. But up until this very moment, he had been unable to oppose even one book.

He stared at the wall before him, at the drawn-up task schedule. The schedules were updated several times a day, so everyone knew, at any given moment, who was reading what. The process was akin to entering a minefield or a jungle full of snakes. A rope should have been attached to each of their backs, he thought, just in case a censor lost their way back to the surface.

It was a large room, big enough for all of them. Each sat at his own desk, a crate full of books awaiting inspection at his feet. Nothing eye-catching, except for the schedule on the wall: each censor had two columns next to their name, one for the books they had finished inspecting and another for the books they were ordered to inspect. The column next to his name was empty except for one book.

It had taken him a while to grow familiar with the preventative measures that censors took to limit the impact a book had on them. At first, he thought it was a lack of professionalism, but he soon learned that everything had a reason. Anxious that the censors might wade too deep into the forest of language and lose their footing in reality, the First Censor, for example, would intentionally cough at certain times when the room grew too quiet. Sometimes he would sneeze, just so everyone would say, “Bless you!” At other times he would grumble about the heat or some other mundanity to interrupt their train of thought. He encouraged each of them to discuss what they were reading, and he would gently swat away any intrusive thoughts. The most valued behavior was to mock what one was reading – whether the book was banned or permitted made no difference. What mattered was your ability to belittle the enemy.

This was what had happened with a poetry collection the day before. “Look here!” the Second Censor cried. “Listen to this:

The sun said

Embrace me

And give me a drink from your forearm.”

He then extended his left arm and began to massage it as if milking an udder. The rest of the censors laughed too loudly and took it a step further, one of them milking his own foot, another pretending to pour water from his ear. When they reached more intimate places, the First Censor scolded their improper behavior, especially with women in the building. Then someone said one could no longer tell the difference between poetry and nonsense, that literary taste was lost, to the point that everyone began wondering: what sort of book was this? By the time their conversation ended, the book had lost all value. Not just the book in question but every other book in the room. Grumbling, they returned to their inspection, more wound up than before.

But such tactics didn’t work for him. He didn’t understand why he couldn’t, even for a moment, hate the book he held between his hands.

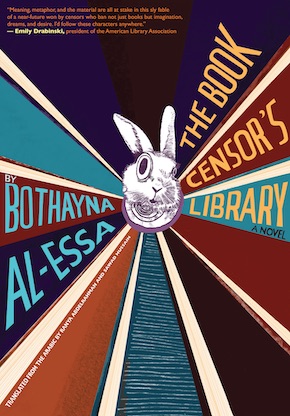

From The Book Censor’s Library, translated by Ranya Abdelrahman and Sawad Hussain (Restless Books, $17.99)

—

Bothayna Al-Essa is the bestselling Kuwaiti author of nearly a dozen novels and several children’s books. She is also the founder of Takween, a bookshop and publisher of critically acclaimed works. The Book Censor’s Library won the Sharjah Award for Creativity in the novel category in 2021 and is her third novel to appear in English, after Lost in Mecca and All That I Want to Forget.

Read more

@restlessbooks

Author photo by Yousef Alabdullah

Sawad Hussain is a translator from Arabic whose work has been recognised by English PEN, the Anglo-Omani Society and the Saif Ghobash Banipal Prize for Arabic Literary Translation, among others. Based in Cambridge, she is a judge for the Palestine Book Awards and the 2023 National Translation Award. Her recent translations include Black Foam by Haji Jaber (Amazon Crossing) and What Have You Left Behind by Bushra al-Maqtari (Fitzcarraldo Editions).

sawadhussain.com

@sawadhussain

Ranya Abdelrahman is a translator of Arabic literature into English. She has published translations in ArabLit Quarterly and The Common, and is the translator of Out of Time, a short story collection by iconic Palestinian author Samira Azzam. She is based in Dubai.

A UK edition of The Book Censor’s Library is published in September 2024 by Selkies House, under the title The Guardian of Surfaces.

@SelkiesHouse