Transformers

by Ann MorganYears ago, when I was starting out as a writer, I met a literary agent. “What do you want to see happen to characters in a story?” I asked him. His reply was simple: “I want to see them changed.”

In many ways, identity change is a central part of most stories. Through the experiences they encounter, nearly all protagonists learn something that alters the way they look at themselves and the world.

However, some works take this further still. These are the ones that feature characters who not only change through the events they experience, but who also deliberately reconstruct their identities (or have them reconstructed for them) for good or dubious ends.

These kinds of stories have always fascinated me because they let us explore how we might all be different if we presented ourselves in other ways. This is one of the reasons I chose to structure my debut novel, Beside Myself, around an identity swap gone wrong – twin girls who change places in a game and then get trapped in the wrong lives when one of them refuses to swap back.

Here are ten of my favourite examples of people, characters and things that change their identities in striking ways:

Rosalind in As You Like It by William Shakespeare

Shakespeare plays abound with characters passing themselves off as other people and finding themselves ‘translated’. There are men dressed as women, women dressed as men and all manner of fantastical beings reconfiguring themselves to befuddle poor, bumbling humans – not to mention poor old Bottom, blundering around with an ass’s head. For my money, however, the most magnificent has to be the witty yet vulnerable Rosalind who dresses herself in doublet and hose, and poses as the youth Ganymede in order to attempt to charm Orlando, with whom she has fallen in love. Rosalind’s repartee is both amusing and bittersweet as we see her striving to keep her feelings in check. “Men have died from time to time, and worms have eaten them, but not for love,” she tells Orlando in Act IV, scene i. Perhaps she’s right, but judging from her own actions, people are certainly willing if not to die then at least to lose themselves almost completely for love.

Mohamed Ahmed in The Sand Child by Tahar Ben Jelloun, translated from the French by Alan Sheridan

How’s this for a premise? Hajji Ahmed Suleyman is the father of seven daughters and the possessor of a big problem: if he and his wife don’t produce a son, his money will be inherited by his brothers when he dies, leaving his widow and children destitute. When his eighth child turns out be a girl, the father takes drastic action. He decides to raise her as a boy and names her Mohamed Ahmed. Only the parents and the midwife know the truth. What follows is a fascinating and troubling account of a person raised in the wrong gender role in conservative Moroccan society and her struggle to find her way towards a self she can accept. The narrative is often as bewildering and mindboggling as the dilemma Mohamed faces, but the overall effect is a powerful and engrossing account of the search for identity, and the lengths to which we will go to feel comfortable in our own skins.

Strasbourg

Strasbourg

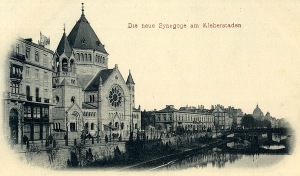

If you like the sound of travelling without leaving the comfort of your own home, you might have done well to have lived in Strasbourg around the turn of the 20th century. The city has changed nationality no fewer than four times since 1871, as France and Germany variously laid claim to it, in addition to a brief stint of independence from both. I visited during a school trip around 20 years ago. Though it was clear that the traumatic events of history had taken a great toll on the town, which lost many inhabitants and architectural gems such as its Romanesque revival synagogue, the richness that this dual heritage had given the city was also apparent. From its handsome buildings in the Gerberviertel or Petite France to the delicious pain d’épices, packed with spices reminiscent of Lebkuchen, Strasbourg is a reminder that changing identity or allegiance can be an enriching process.

David Bowie

It would be hard to write a piece about people and things that alter their identities without mentioning David Bowie, particularly this month in the wake of the news of his death. With his clutch of alter egos – Ziggy Stardust, Aladdin Sane and the Thin White Duke – as well an aesthetic that shifted through as many modulations as his music over the years, the artist was an inspiration for millions of music lovers, huge numbers of whom describe him as a transformative influence on their own lives. Adopting and discarding various gender markers, he was also instrumental in changing prevailing attitudes to gay and transgender rights in recent decades. In many ways, his fluidity and chameleon-like nature was part of his essence: his remaking of himself characterised his five-decade career.

Beatrice-Joanna in The Changeling by Thomas Middleton and William Rowley

As transformations go, they don’t get much more dramatic than the one depicted in this celebrated Jacobean tragedy. Starting the play as the chaste, beautiful intended bride of Alonzo, Beatrice ventures on the road to her ruin when the idealistic young Alsemero catches her eye. Infatuated with him, she commissions her father’s servant, the prophetically named De Flores, to kill Alonzo. But there is a price: in order to perform the murder, De Flores demands the reward of Beatrice’s virginity. After much agonising, Beatrice acquiesces, only to find that she relishes her experience with De Flores, despite his ugliness and vulgarity. The two embark on an affair, while Beatrice continues to string Alsemero along, becoming ever more lustful and attached to De Flores with each secret encounter. Torn between her reputation and the reality of who she has chosen to be, Beatrice cannot hope to survive.

Mr Benn

Although the TV version of the books by David McKee aired first in the early seventies, I remember watching the programme as a child in the 1980s. There was something deeply engrossing about the story of the little bowler-hatted character who would visit a fancy-dress shop each week to be presented with a costume that would allow him to have an adventure in a corresponding world. It was what I always hoped would happen when I played dressing up or embarked on one of the imaginary games that would sometimes go on for weeks of break times at school – that the make-believe could be real, even for a moment, and that I had the power to become someone else.

Lili Elbe

The story of the Danish artist Einar Wegener, one of the first people known to have undergone sex reassignment surgery, is big news at the moment, thanks to the release of Tom Hooper’s The Danish Girl. While that movie is based on David Ebershoff’s novel of the same name, a fictionalised account that does not always stick strictly to biographical facts, it does capture Elbe’s bravery. Although change for most of the entities on this list is a psychological or sartorial matter – something that at least has the potential of being reversed or modified further down the line – for Lili Elbe it was a one-way procedure that would be inscribed permanently on her body. The surgery’s novelty and experimental nature also meant that it had a high chance of proving fatal and might destroy not only Lili’s former self, but the new self that she so desperately wanted her body to reflect.

c. 1677. V&A” width=”200″ height=”264″>John Wilmot, Second Earl of Rochester

c. 1677. V&A” width=”200″ height=”264″>John Wilmot, Second Earl of Rochester

This notorious wordsmith and libertine of the court of Charles II was given to extreme behaviour on many fronts. Not only were his excesses legendary, but he is credited with being one of the English language’s most obscene poets (although his translation of part of the chorus from Seneca’s Troas is memorable for its quiet dignity and is among my favourite pieces of writing). Among his more eccentric behaviours the maverick earl had a penchant for dressing himself up as a tinker or a quack doctor and going out to ply his trade on the streets of London. In an odd echo of this centuries later, his namesake Rochester in Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre dresses as a fortune teller to read the palms of his guests.

Cinderella

The classic rags-to-riches fairy tale beloved of aspiring princesses everywhere has an identity shift at its heart. Slighted and abused in her kitchen squalor, Cinderella becomes a stunning beauty with the help of the fairy godmother and turns every head at the ball. Underneath it all, she remains herself, however, as the glass slipper reminds us: it fits regardless of the setting. Much like its heroine, the tale itself has been through drastic alterations over the centuries. Versions vary from the saccharine – think the singing mice in the Disney animation – to the sinister. In its most violent incarnation, the bullying sisters chop their heels and toes off in an effort to make the glass slipper fit, before having their eyes put out by birds.

Don Quixote

Perhaps there is a little of Miguel de Cervantes’ ‘ingenious gentleman’ in all of us – or certainly in those of us who love books. Having read himself into a kind of insanity with a literary diet featuring too many chivalric romances, the nameless protagonist of the book proclaims himself a knight, Don Quixote, and sets out to right the world’s wrongs and re-establish chivalry, co-opting a farmer to be his squire along the way. To most of the people he meets, it is quite obvious that Don Quixote is not the hero he fondly imagines himself to be. But in his own mind, he is a giant among men, a crusader for all that is good and true. As a result, the scrapes Don Quixote gets himself into are at once funny and touching – we can laugh at how ridiculous he is, all the while recognising that his delusions of grandeur are all too human.

Ann Morgan is a London-based freelance editor and writer. Her first book, Reading the World: Confessions of a Literary Explorer was published by Harvill Secker in February 2015. Her debut novel Beside Myself is published by Bloomsbury Circus in hardback and eBook. Read more.

Ann Morgan is a London-based freelance editor and writer. Her first book, Reading the World: Confessions of a Literary Explorer was published by Harvill Secker in February 2015. Her debut novel Beside Myself is published by Bloomsbury Circus in hardback and eBook. Read more.

ayearofreadingtheworld.com

@A_B_Morgan