The unbearable burden of non-being

by Mika Provata-Carlone

“A narrative that is vital for our times.” European Lirerature Network

Lviv, also known as Lwów and to others as Lvov, as Antonia Lloyd-Jones reminds us in her translator’s note, or to some as Lemberg and even Leopolis, is a city with a rich enamel of history – it is almost majolica-like in its many facets, colours, hues and patterns, in the broken splinters of its tesserae that in their synthesis make up for an urban and cultural whole that still seeks its sense of unity and uniqueness. If a city is the shell of its buildings, the genealogy of its architecture and the morphology of its public art, then Lviv, to give it its current name, can be picture-perfectly enchanting, combining Mittel Europa gravitas with Italian bravado and sensuousness, adding Slavic hyperbole in a twist of panache. Like Troy, Lviv was sieged and attacked ferociously, repeatedly across its long history. It has been a war zone, a battleground, the heart of vicious internecine or multi-ethnic conflict and unutterable atrocities. Unlike Priam’s city, the many layers of the material corporeality of its polis remain intact – each coexisting and fraternising with the other as a constant reminder of the many faces, voices and traditions that formed, once, the city’s soul, as echoes, soft or howling, alluring or outright terrifying, of stories that even if told, were often refuted, smothered, erased.

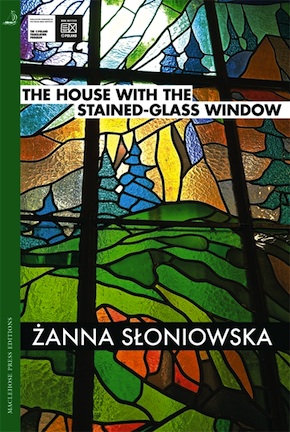

In The House with the Stained-Glass Window, Żanna Słoniowska aims audaciously, but also elegiacally, to reunite the carcass of stones, statues, landmarks and homes with one part, at least, of its ailing soul. She is guided by three axiomatic principles in this: the city’s evocative beauty, transcendental and real, the undying power of the city’s soul, and the extreme condition of its ailment. The novel begins with a death that kicks off a life, and perhaps the ending mirrors the beginning, a circle come full spin, in a Vico spiral of still very troubling history.

“We are like Russian dolls, one in the belly of another, it’s not entirely clear which is inside which, all that’s apparent is which is alive and which is not, we are like Russian dolls transpierced by a single shot,” says the narrator towards the end, placing a heavy burden of meaning on the span of four generations, on the continuity that flows from mother to daughter with searing repetitiousness and inevitability, unyielding predestination, but also a rare sense of destiny. The set of matryoshkas is incomplete, defined by the gaping wound in the middle – and at every joint. The sense of time and continuum is also fragmentary, as is our insight into characters, events, the experience of history and, again, time – real and eschatological, or as the arbiter of change, permanence, destruction or infinity. Słoniowska’s writing is as vigorous as it is oneiric, as maturely pungent as it is elliptical. The narrative voice is that of a child as recalled by the adolescent-adult, a retrospective consciousness creating convex and concave reflecting surfaces, magnifying or distorting as it seeks clarity of vision and an equilibrium for existence. On a different level, this disjunctive, allomorphic prism into the story and survival of a city and of individual lives reflects what emerges as the almost psychotic character of the identity of Lviv but also of its inhabitants: ethnic, religious, national, historical, ideological, artistic, ultimately spiritual and often simply human.

This is an intricate, opulent story, resplendent in its shadows and flashes of brilliance.”

Four women with stories screaming to burst out of sealed, dead, unripe or shrivelled lips; men who exist as foils or as titanic determinants of fate; art as the lens of truth, as the power of genuine being and as a fatal mirage, blurring ideals with monstrosities. Love, female rites of passage, an education, wriggly roots and clean new shoots, everything is part of this vastly ambitious, urgently told story. We move in and out of time and spaces of memory, or of unrealised dreams, within a moral numbness and existential limbo that the narrator assigns to the Soviet era of the city. The tone is full of nostalgia and poetry, the poetry of the Silver Age poets, the art of early twentieth-century Vienna, the music of Chopin; it is full of fear, real fear from possible, actual brutality, from unspoken, unspeakable memory, or the undefined, inarticulate terror of the limitlessness of oppression and its possibilities of horror. Language marks lives, points in time, hope and despair: Russian for the Grand-Grandma (who speaks of God only in Polish), Russian for her daughter Ada, who feels Polish, shifting dialects and allegiances for Marianna, the missing matryoshka. The narrator will claim herself a Lvivian (or a Leopolitan) and write in Polish. Her Lviv is Lwow. Or is it?

There is an Autumn Sonata feel to the relationship between the narrator and her mother Marianna, an opera singer whose voice can fill spiritual and revolutionary voids, but not lives, Bergmanesque darkness with Kundera-like lightness and roughness in the depiction and relief of characters. The atmosphere throughout is a striking, gripping blend of finely balanced verbal and situational comedy, particularly delicate, yet unflinching exposures of the human psyche, the mere physis of the body. If there is truth in the statement that at the heart of the Slavic soul is exaggeration, The House with the Stained-Glass Window would certainly offer good proof of it: it brings together gaily, soulfully, with brio and melancholy, a strong folklore vein with a modernist abandon and an absurdist/surrealist tradition. The influence of Russian/Soviet writing – the flighty humour of Teffi, the dark comedy of Chekhov, Bulgakov, Gogol and Nabokov, Vera Panova, or Tatyana Tolstaya, is subtly behind Słoniowska’s own pitch and voice, together with the consciousness of being part of a whole far greater than the sum of its parts, as well as of a heritage that combines the methodical, fearsome farcicality of the Soviet era with an ever evasive, deeply rooted need for identity – Soviet analytics crossing paths with magic realism, human frailty and the despair of burlesque.

This is an intricate, opulent story, resplendent in its shadows and flashes of brilliance, thoroughly engaging. It issues with each scene or episode an irresistible invitation to decipher and find meaning, connections, to reforge broken links of memory, of historical, cultural and personal significance. It seeks to offer a morphology of existence in a landscape where tectonic shifts follow hard one upon another, to consolidate a sense of will over fate, in a cosmos of the most elusive (often slimy) ambiguity. Among the laughter and the tears, there is brutality, coldness and harshness, by history and by individuals. There is a troubling sense of timelessness, or of a fish-eye perspective into time, whereupon many, tangled roots and rootlessness, stories and the state of forced storylessness, acquire a gargoyle-like focus and deceptive frame. The House with the Stained-Glass Window makes unsettling, yet engrossing reading, as images of the city’s architecture, its history, clash with current Ukrainian headlines and older, stifled voices and lives – of the alternately dominant ethnic Slavic groups, of the horrifically, relentlessly decimated Jewish community, that in the end gets an eerie mention in this novel of rebirth and catastrophe.

Słoniowska has written a story that is infused with the rare gift of a genuine voice enveloped in intriguing mystery. Pain and a deep human gentleness combine with fluid, rich elegance. A tighter control of the somewhat scrambled episodic structure of the narrative, a cleaner feel to the texture of passionate youthfulness in the narrator’s voice, would have made this into a truly remarkable piece of writing, and it is certainly a deeply poignant, charismatic novel, fully resonant in Antonia Lloyd-Jones’ masterfully fluent translation.

Żanna Słoniowska was born in 1978 in Lviv and is a journalist and translator. She now lives in Kraków. She is the first winner of the Znak Publishers’ Literary Prize, for which The House with the Stained-Glass Window was chosen from among over a thousand entries. In 2016, she won the Conrad Award, the Polish award for first novels. The House with the Stained-Glass Window, translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones, is published by MacLehose Press in paperback and eBook.

Żanna Słoniowska was born in 1978 in Lviv and is a journalist and translator. She now lives in Kraków. She is the first winner of the Znak Publishers’ Literary Prize, for which The House with the Stained-Glass Window was chosen from among over a thousand entries. In 2016, she won the Conrad Award, the Polish award for first novels. The House with the Stained-Glass Window, translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones, is published by MacLehose Press in paperback and eBook.

Read more

Author portrait © Adrian Błachut

Antonia Lloyd-Jones is a full-time translator of Polish literature, and twice winner of the Found in Translation award. She has translated works by several of Poland’s leading contemporary novelists including Paweł Huelle and Jacek Dehnel, and authors of reportage including Mariusz Szczygieł and Wojciech Jagielski. She also translates crime fiction by Zygmunt Miłoszewski, poetry by Tadeusz Dąbrowski, biographies, essays, and books for children.

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.