Diving into Wonderland

by Mark Reynolds Something is stirring underground at London’s Waterloo, as two immersive shows share a lovingly created Wonderland to mark the 150th anniversary of Lewis Carroll’s Alice. I sit down with co-directors Oliver Lansley and James Seager from theatre group Les Enfants Terribles and producer Emma Brünjes to peer down the rabbit-hole.

Something is stirring underground at London’s Waterloo, as two immersive shows share a lovingly created Wonderland to mark the 150th anniversary of Lewis Carroll’s Alice. I sit down with co-directors Oliver Lansley and James Seager from theatre group Les Enfants Terribles and producer Emma Brünjes to peer down the rabbit-hole.

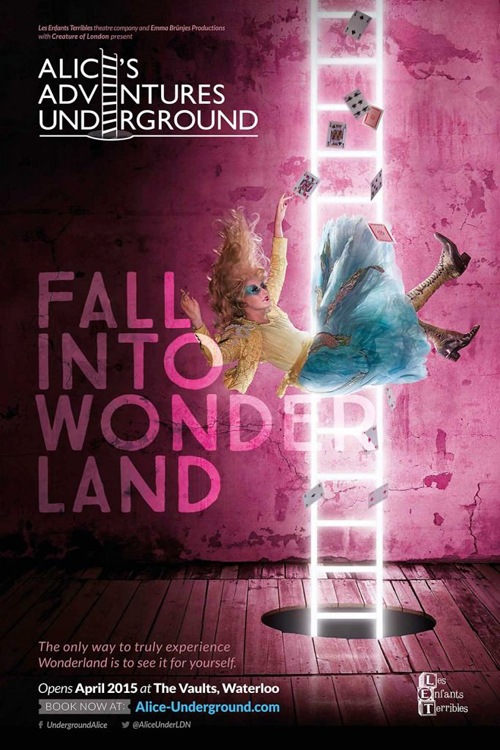

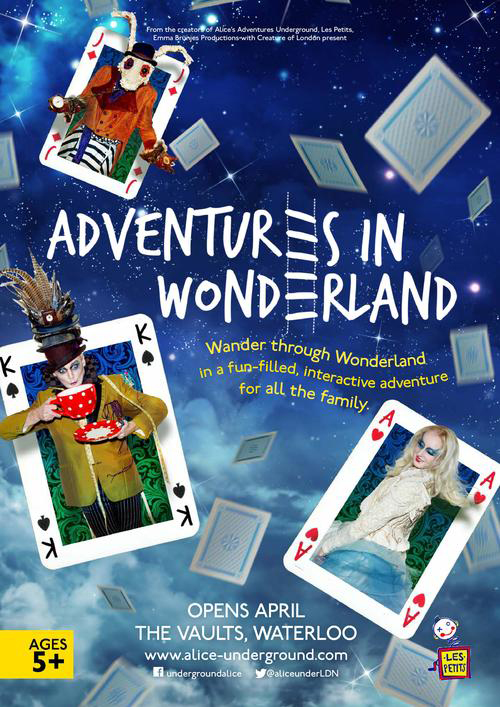

Alice’s Adventures Underground, and its sister show for five-year-olds upwards, Adventures in Wonderland, combine puppetry, costume, drama, live music, circus and spectacle to give a delightfully entertaining and wholly satisfying twist on the adored children’s classic. In both shows, audiences are faced with the choice of an Eat Me or Drink Me route into Wonderland, before scurrying through the mazy underworld in small groups, encountering familiar characters in striking guises, and exploring the fantastical world with eyes wide open to new surprises.

On Monday nights at The Vaults, when other theatre spaces lie idle, the Wonderland Sessions are a carefully curated series of talks giving insight into the deep influence of Carroll’s work in all aspects of our culture, bringing together special guests from the worlds of art, theatre, fashion, film and dance. More than three years in the planning, the shows’ creators are proud, dizzied and infectiously enthusiastic about their ambitious journey.

MR: What first sparked the idea of adapting the Alice books? Was it always geared to the 150th anniversary, and at what point did The Vaults emerge as the venue?

Oli: They’re all quite integrated, those three things. It had been an idea for a while to create an entire world somewhere, and when Alice came up it seemed like a very obvious choice because it’s one of those books that when you read it, as much as you’re taken in by the story, the real thing that jumps out at you as a reader is the desire to visit the place, to go there and to experience the world and to meet the characters. Alice in Wonderland is such a unique piece of literature in the way that it ignores most of the rules that we think there are in terms of storytelling and what makes a satisfying experience. It’s a challenge to adapt because it’s non-linear, a series of sketches, explorations and musings. Rather than it being a choice of going, “Let’s do an immersive show, what world can we use?”, it felt very much like Wonderland lent itself to being told in this way. So the idea was hanging around in our heads, and we knew Kieron [Vanstone] who took over The Vaults a couple of years ago, so we went down there. There aren’t many spaces in London with the kind of footprint to be able to create Wonderland, and The Vaults being underground, it seemed absolutely perfect. It was 2013 when we had The Vaults in our head, and Kieron was interested, and then when we realised the 150th anniversary was coming up, we sort of went, “Well this is it, it’s now or never.” We met up with Emma in early 2014, and it was almost exactly a year from our first meeting to our first day of rehearsals.

Emma: The first meeting was 29 January 2014 – it’s etched. It was a no-brainer when we sat down for a coffee and the guys told me the idea. I was like, “Absolutely, and absolutely it has to happen next year.” And we went into fifth gear.

James: It’s been a lot of work: meetings and logistics, planning and producing the show and getting people on board. We’ve been blessed, we’ve had an amazing team, from lighting teams, designers, puppeteers… We’ve spent the last year approaching the best people and the people we wanted to work with, and they’ve all loved the idea and we’ve built a great team.

Oli: The biggest thing was the logistics of what we wanted to achieve with the show, which was primarily that we wanted to build a complete world that you could wander around. The method of theatre and storytelling we wanted to use I don’t think has quite been done on this scale before, to create an experience which allows the audience to have an element of choice, but also allows an element of freedom that gives everyone a different but equal journey. To be able to do something on this scale necessitates a certain number of tickets to be sold but we still wanted to give people as intimate an experience as possible. So although over 650 people go through the show each night, most of the time your audience is no more than 14 people. And we wanted it to feel intimate and that you’ve got a chance to directly interact with the world. So the logistics of planning that was extraordinary.

Emma: Oli and Anthony Spargo, the co-writer, had written a first draft of the script, to which we all sat down and wrote a budget that then developed. It became very clear that the show was going to be planned in exacting detail, both financially and creatively, by spreadsheet. I’d never seen a show that has a script and a spreadsheet side-by-side. Even when the actors got their offers, they were given a script and a rota and a spreadsheet and a time code to read.

James: One of our biggest desires with this production is to give everyone a story. There are several story strands that converge throughout the show. Obviously in a normal piece of theatre you sit an audience in a certain spot and they all look at the same thing, so it’s easy to deliver pieces of a story to them. Or in a lot of immersive shows you wander around and the story happens and it’s up to you how much you get of it. We had to juggle how to deliver story while also giving people a sense that they’re wandering through a world. But ultimately giving our audience a story they could follow from start to finish.

And the spontaneity and surprise are kept at a level all the way through, I found. In both shows, you get a sense that people in the same room, never mind those who have taken a different path, are having a highly individual experience. So what would audience members miss by not coming back to seeing the show again?

And the spontaneity and surprise are kept at a level all the way through, I found. In both shows, you get a sense that people in the same room, never mind those who have taken a different path, are having a highly individual experience. So what would audience members miss by not coming back to seeing the show again?

Emma: There’s a cast of 30, plus 12 card guards, on the adult show, and they all play multiple roles as the audience splits into four groups at 15-minute intervals. We gave all these numbers to a statistician in the City and he couldn’t work out how many times an audience member could come back and have a very different experience. We flummoxed him.

Oli: In the courtroom scene for example, within a night as the scene rotates we have six different Kings, three different Queens, six different White Rabbits. When you’re trying to run a scene as a director you might go, “Right this needs to be pacier,” then you get a different Rabbit coming in whose tempo is much higher. And because the whole show is run on a time code, it’s the most complicated thing.

James: In rehearsals, Oli and I would be directing one scene and then we’d have to do it again, and again, and again, and again…

Oli: It was like directing five or six rehearsals at the same time.

James: But it was 100% the right thing to do. If you’re doing the same scene up to 36 times a night and seven or eight times a week, then it seems that the actors should rotate the roles for their own sanity. Which hopefully brings a freshness to the piece as well.

We had a version where all the audience got to see everything, they just went through a different route. But we soon found that for this sort of show and for this sort of experience, sometimes what you don’t see is just as important as what you do see.”

Oli: Very early on we had a version where all the audience got to see everything, they just went through a different route. But we soon found, through a lot of workshops and development discussions, that for this sort of show and for this sort of experience, sometimes what you don’t see is just as important as what you do see. We always encourage people turning up at the show together to split up between Eat Me/Drink Me and the different suits, and I think the joy of the show is being taken on your own journey, then coming back together at the end. By the time the audience gets to the courtroom scene they have been split into tribes each with their own sort of in-joke, and people see their friends reacting to different characters and having relationships that they know nothing about.

James: When the show finishes and people are in the bar you overhear the audience talking to each other and saying, “Did you see this?” “No, but did you see this?” And that’s really exciting, hearing that buzz of people comparing their routes.

Oli: It was a risk, and sometimes it seems crazy. The Mock Turtle space, which is this tunnel that we flooded where it rains, and contains an extraordinary moment of performance, you spend a lot of money and time creating a moment like that, and then only half of our audience is going to see it. We talked about this a lot, and realised that to really get the most out of the show you have to embrace the spirit of what it is. In theory we could have controlled it more, but I think the heart of what Wonderland is that it’s disorientating, it’s alive and it’s wild, and I think the audience embrace and understand that.

James: It’s also about making all the routes and experiences equal, so that people who don’t see the Mock Turtle, for example, get to experience the Caterpillar and an amazing projection-animation.

Oli sets out a rhetorical question in the foreword to the programme, but I’ll ask it anyway: “How do you give people what they want, whilst also giving them something they’ve never seen before?”

Oli sets out a rhetorical question in the foreword to the programme, but I’ll ask it anyway: “How do you give people what they want, whilst also giving them something they’ve never seen before?”

James: It’s a difficult one that we’ve been talking about for a lot of months. People do have their perception, people think they know what the Mad Hatter’s going to look like in their imagination, from reading it or seeing Disney versions, so you’ve got to pay homage to that, but you’ve also got to challenge them a little bit.

Oli: It’s like finding people’s subconscious tick-boxes, and that was a big thing about the routes as well – “If I go to Wonderland and I don’t get x, y, z, I’m going to be disappointed.” – you have to be aware of that expectation, but at the end of the day we just need to tell our story, and do it the way that we feel it should work, and hope that works for other people.

James: We were keen not to stray too far away from the original text as well. You’ve got to put your own spin on it, you’ve got to put your narrative to it, but at the same time we didn’t want to reinvent the wheel and make some kind of drastically different Hatter or drastically different Mad Hatter’s Tea Party. Because it’s an amazing book, and people love it for good reason, so it’s a balancing act of having your own take but paying homage, and hopefully that’s what we’ve got.

Oli: We tried to take as much from the book as we possibly could. I mean, the Tea Party is literally almost word for word. It’s in a different order and it’s mashed up and it’s gone through our filter, but as much as possible our starting point for everything was the book; our starting point for every scene was taking those sections out of the book and then working them into our story.

Emma: I suppose the biggest step, from an audience point of view and their experience, came in the development stages in October last year. I got down to rehearsals and Oli pulled me to one side and said, “Don’t panic, but Alice isn’t going to be in Alice in Wonderland!” And I said, “OK… ” But it was completely the right decision, because it makes the audience become Alice. We are building a world, we are putting it there for you, but you are going on her journey. You’re not watching her journey as a voyeur or as a third party, and that’s why you have that sense of involvement and excitement.

James: The Tea Party’s a very good example of that. The moment you put Alice in the Tea Party you’re watching her interact with the Hatter and the Hare, and we realised that it allows you to detach and feel safe because you’re watching someone else’s experience, but if you take that conduit away, suddenly there are people looking at you…

Emma: In the children’s show [directed by Emma Earle] it’s so sweet, because they spend the hour going, “Where’s Alice? Where’s Alice?” and then she appears – in that lovely moment I won’t ruin. It’s fantastic, and helps give them a sense of ownership of Wonderland.

This Wonderland is made real by a feeling of subterfuge and revolution against the tyranny and unpredictability of the Queen. How soon did you realise this aspect would be key to both shows?

This Wonderland is made real by a feeling of subterfuge and revolution against the tyranny and unpredictability of the Queen. How soon did you realise this aspect would be key to both shows?

Oli: One of the key messages of the book is about not growing up. Lewis Carroll’s obsession with the seven-year-old Alice and wanting her to remain like that forever, the kind of inquisitive nature and innocence in the way that children see the world, is something that kind of gets beaten out of us. The name of our theatre company, Les Enfants Terribles, tells you a little bit about who we are and what we like to do, and we like to have that sense of mischief. We like to bring people into our worlds and say, “Stop being a cynical, hipster theatre critic and just allow yourself to come into Wonderland for an hour and a half and be a child again.” That was the essence of what we were trying to create.

James: Straightaway we set up the tyrannical Queen, and that led us to consider what the other cards meant, and the role of the audience. Obviously if you’re Hearts, then you’re affiliated with the Queen, so then we started thinking about what the other three suits would mean, and it developed from there. Then we came up with WURM, the Wonderland Underground Resistance Movement, and how our characters could fit into that, and then the different routes through Wonderland really developed.

Oli: Another thing is, our Wonderland is Wonderland 150 years after Alice arrived, so it was sort of an extrapolation of what has happened to the world in that time. Alice spends a lot of the book trying to put her own Victorian sense of logic to this world of no logic, so we took that nugget and thought, so where does that lead us 150 years later, and then came the idea of nonsense being banned.

Emma: We’ve all experienced immersive or interactive shows where you sometimes lose the sense of narrative, and that was something that was driving us, and we wanted our audience to feel part of it. Giving each of the audience an individual card and identity was every bit as important as taking Alice out.

Was there always going to be a children’s show alongside the adult show?

Was there always going to be a children’s show alongside the adult show?

Oli: It’s such an important piece of children’s literature, and I think very early on we realised that if we tried to squeeze everything into a one-size-fits-all show we would have to make compromises. Adventures in Wonderland has allowed us to provide an experience for younger children than we would’ve been able to with a single show, and it means that we can create an experience that will be more satisfying for them than trying to have the same experience that, say, a 30-year-old theatre-goer from Hoxton would enjoy. We set up our own specific children’s theatre company, Les Petits, because we wanted to create children’s work that worked on the same levels as our grown-up shows do. And there’s much more responsibility doing children’s theatre, because kids go into these worlds and they accept stuff, and it stays with them. It’s a really exciting but privileged position to be in, to create these experiences for young children.

James: They are very honest, kids. An adult audience might see the amazing puppetry and masks and enjoy the design and technicality of it, but a kid will see the Cheshire Cat or the Rabbit and they won’t think of the design of it, they’re either “Yes, I believe that” or “I don’t believe that.”

Oli: You don’t get any points for artistry. Either they’re engaged or they’re not engaged.

Children love the interaction with the characters. And that’s great, because it means you’re converting children to live theatre, live entertainment, at a really early age, and you’ve got them away from a TV or a computer game.”

Emma: I went through one of the very first audience intakes with the children’s show, and as this little boy got to the Eat Me/Drink Me point he collapsed in tears saying, “I don’t want to grow, I don’t want to grow!” But then I saw him at the end with the flamingo croquet, happily wielding it around the bar. They want to come back, they’ve never really seen anything like this, and they love the interaction with the characters. And that’s great, because it means you’re converting children to live theatre, live entertainment, at a really early age, and you’ve got them away from a TV or a computer game. And they’re all turning up in costume, which is delightful. We get lots of Alices, and girls dressed as the Red Queen, and little boys with rabbit ears.

Do the Wonderland Sessions take place in a single space, or around the venue?

Emma: It’s the most traditional thing that we’re doing, because we put seats out and everyone sits and looks at the stage for the most part. But they’re very much driven from us saying we’re not just putting on a theatre show, we want to celebrate this book, the influence of this book across all the media.

Oli: They’re so fascinating. It makes you realise the impact this book has had on so many different elements of our culture, and on so many different people. The first one was ‘Being Alice’, where we had a selection of incredible women who had played Alice over the course of their careers. Then we had Alice Liddell’s great-granddaughter come in and talk about Alice herself, and people like Fiona Shaw…

Emma: … and Bob Crowley, who was just nominated for a Tony. It’s fantastic and we’re very honoured. It just shows the power of this piece of literature.

And are the Sessions going to continue all the way through August as well?

Emma: Yes, they’re going to be in a slightly different guise, we’re just working that out at the moment. Be we built this space and we want as many people as possible to see it…

James: … and to keep Monday active. That’s really exciting for us, engaging a different type of audience in a different type of way on a Monday nights when the actors take a break.

Emma: I feel the same about West End theatres, they are these beautiful buildings that people only see for three hours a night, and I feel strongly about showing off the Wonderland we created. One of the other things we might introduce during the summer holidays is play coffee mornings for mums with children under 5, so there’s all sorts of other things we want to try and do in the space.

How would you go about transferring the shows elsewhere? How many of the sets are site-specific and would need to be rethought?

James: You can do that and we’re looking into it. How we do it will be determined by the architecture and location.

Oli: The main thing is finding enough space. The thing with The Vaults is it gives you a lot for free on certain spaces, but it makes your life very difficult with other spaces. In the Tea Party we get a lot for free, but then there are other spaces where you’re really working against the fact that you’re in a tunnel.

Emma: We’ve created lots of rooms-within-rooms in some places.

Oli: Every venue I assume would give you advantages in one area and disadvantages in another area.

Emma: Our intention is very much to take it to other countries, hopefully, but it will have to just tweak. The fundamental elements will not change – because we don’t want to be rewriting the show!

Oli: Now we’ve got the building-blocks I think we all feel confident about our ability to recreate it.

Emma: We’re in conversations with New York, LA, Sydney, so we’re ambitious to try and push those territories. I was talking to someone only last night and he said, “Oh, the Japanese would love this,” and it hadn’t even occurred to me, and I thought, “Yeah, absolutely.” We’ve had also emails from people in the Middle East. Now that we’re open, and we’ve all had a couple of nights’ sleep, it’s definitely something we’d really love to do. We’re super proud of it.

Alice’s Adventures Underground” width=”320″ height=”213″>Oliver Lansley (Director, Writer and Producer, right) is Artistic Director of Les Enfants Terribles, which he founded in 2002. As an actor he is best known for playing Kenny Everett in the BAFTA-winning The Best Possible Taste (2012).

Alice’s Adventures Underground” width=”320″ height=”213″>Oliver Lansley (Director, Writer and Producer, right) is Artistic Director of Les Enfants Terribles, which he founded in 2002. As an actor he is best known for playing Kenny Everett in the BAFTA-winning The Best Possible Taste (2012).

James Seager (Director and Producer, centre) is Les Enfants Terribles’ full-time director and producer. Initially involved with the company as an actor, he moved to producing and directing shows in 2005.

Emma Brünjes (Producer, left) established Emma Brünjes Productions in 2013, where she works as a producer, promoter, general manager and agent. She was previously Head of Avalon Promotions, producing and promoting UK-wide comedy tours, and Manager of Productions & Programming at Nimax Theatres.

Alice’s Adventures Underground and Adventures in Wonderland continue at The Vaults until Sunday 30 August.

More info.

Read our junior reporter Malaika Cowen’s review of Adventures in Wonderland.