Chigozie Obioma: Tangled lines

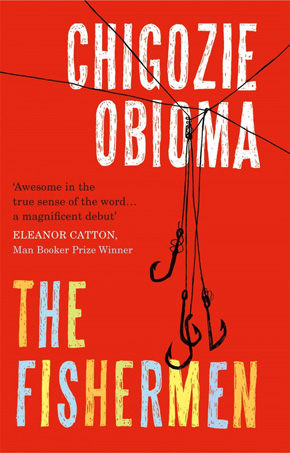

by Mark ReynoldsTold from the point of view of Benjamin, the youngest of four brothers, Chigozie Obioma’s powerful debut The Fishermen is the story of a childhood in 1990s Nigeria. When their father has to travel to a distant city for work, the boys take advantage of his absence to skip school and go fishing. At the nearby river they encounter a madman called Abulu, who predicts that one of the brothers will be killed by ‘a fisherman’ – a prophecy that sets into motion a tragic and transformative chain of events.

MR: On the back flap, you say “The Fishermen first came to me as a tribute to my many brothers, and a wake-up call to a dwindling nation…” How much of the detail is autobiographical, and what are the most calamitous ways in which Nigeria is dwindling?

CO: That was a reference to the origin of the novel. I was away from Nigeria, in Cyprus, and I was homesick, and I had this call from my dad one day and during the conversation he mentioned my two oldest brothers, who used to have this sibling rivalry growing up which would sometimes spiral into violence. And he mentioned that they were so close now, in their early 30s. And after the conversation I just started to reflect on what was the worst that could have happened during those days when they would beat each other up. The idea of writing a story about a close-knit family came up, and then I wanted to explore the idea of an external force that would come in from the outside and destroy a united family.

Nigeria is a conglomerate, a montage of different nations. The Igbo nation, for example, is about 40 million people, and that’s just one tribal region. The country is a construct of the British, a contraption that is not sustainable. Thriving nation-states, with their own identities, were merged together. I was also thinking of what the American historian Will Durant said, that a great civilisation cannot be destroyed from the outside, only from within. So just as the nation-states yielded to the force of this external power, the boys yield to the external authority of the madman.

The story came to you while you were living in Cyprus. Would you have told the same story if you’d stayed in Nigeria?

I don’t think I would have. The story became the dominant thing in my mind at the time I left Nigeria. To write about the place, I had to withdraw from it, and trust in the power of hindsight.

At what age did you leave Nigeria, and under what circumstances?

I was about 22. I was in this Nigerian college, studying Economics. When I was growing up I would say I wanted to be a writer. I wasn’t necessarily discouraged, but people would be sad or afraid for me: You’re going to end up in penury, why not just be a lawyer or something and write on the side? But I wanted to study the tradition of literature, and with some luck I was able to convince my parents to let me go. London was of course where I wanted to come, but the UK border control wouldn’t give me a visa, so Cyprus somehow came up as the next viable option. It had to be a school that was affordable, America was out of the question.

How often do you visit Nigeria at the moment, what keeps you from going back, and how much longer do you expect to be based in Michigan?

Nothing keeps me from going back, I go once a year or so. I will leave Michigan for the University of Nebraska, Lincoln in the fall, when I begin as assistant professor of literature and creative writing. I expect to be in the States for some time.

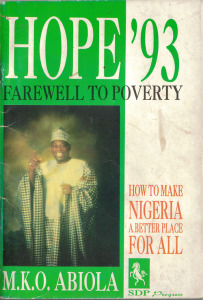

The boys grow up admiring M.K.O. Abiola’s vision for a new Nigeria. If his election win had been allowed to stand, how would Nigeria’s recent history have played out differently?

The boys grow up admiring M.K.O. Abiola’s vision for a new Nigeria. If his election win had been allowed to stand, how would Nigeria’s recent history have played out differently?

We have this saying that if something does not happen, it’s better not to imagine, it’s better not to try to create it. But if he had won, I think he was the one politician or presidential aspirant who actually had the most comprehensive and clear agenda for Nigeria. I was small in 1993, but he was very, very assertive about what he thought he could do to make the country work, to change the paradox that is Nigeria: oil-rich, massive human resources in a population of 170 million people, a very strong and vibrant educated class of people, and still inefficient as a nation. So I think he would have been able to bring something good to the table.

What do you understand to be the circumstances of Abiola’s death, when he was found dead in prison on the day he was scheduled to be released?

You will have noticed we have a tendency to be very superstitious in Africa, and that is a fertile ground for conspiracy theories to grow, but I do think that he was assassinated. It was not a coincidence. He’d survived prison for very long, so for him to die like that is suspicious. There have been books written about it, but people disagree.

Ben’s brother Obembe is a book lover, and Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart is a looming presence. How influential has that book been on your own writing?

My major influence was not Achebe, but Amos Tutuola, the Yoruba writer who wrote the first novel by an African in English [The Palm-Wine Drinkard]. But Things Fall Apart became very popular. Achebe is an influence because his work is grounded in Igbo philosophy, you read him to learn something about the history and the culture of the people, a lost tradition and civilisation.

There’s a saying that if you want to hide something from an African, put it in a book, and to a great extent it’s true. I take my family as an example.”

You told me earlier there isn’t a strong literary tradition in terms of book buying in Nigeria. Why do you think that is?

It is an unfortunate situation but literary culture is almost zero, you are an anomaly if you engage with books. There’s a saying that if you want to hide something from an African, put it in a book, and to a great extent it’s true. I take my family as an example. There was a short-story version of the novel, and there were copies of that journal in my house for many years. I have eleven siblings, and only my dad and my younger sister have read it. No other person. Five times more Americans, and maybe British too, have read Things Fall Apart than Nigerians. Reading is seen as a taxing experience, whereas it’s easy to watch movies. But there’s something that comes with engaging in a text, it’s a conversation with your mind in a way that very few other art forms can challenge you, and I think you have to acquire the facility from a very young age.

So at what age did you become an avid reader?

I came to reading through an almost desperate love for storytelling. I grew up hearing my mom and my granny telling stories, and also my father. I was fascinated by this idea of escape, of alternate worlds, how people can create reality just in their head, in their imagination, and each time I hear stories these faces seem to rise from nowhere. Every story I heard, I would go tell my friends at school.

When I was about eight or nine I was sick in hospital with malaria or something, and my dad would sit by my bedside and tell me stories. Then when I was well, one day he came back from work and I asked him to tell me a story, and he said, “Go and read it yourself,” and he gave me a book and I went and read it and discovered that one of the most fascinating stories he’d ever told me was inside it! That was a secret before then, so that was a pivotal moment. Prior to that I had always seen my dad as this great man who had this vast reserve of stories, but then I saw I could actually get this thing from books, and I started reading voraciously. And then I began to replicate the stories in written form, so that was the point where I moved from a storyteller to a writer.

The way Ben equates family members and others around him with distinctive animal characters lends the book a mythical quality, which is also helped along by Ben’s innocence and inexperience. At what point did you decide to begin the story through the eyes of a nine-year-old boy, and why?

I wanted to be able to capture this moment of growing up, this coming of age, I wanted the storyteller to be present in the story, to tell the story in a linear form: this is where it started, and this is where it ends. So to be able to do that I had to take him back to that time when it all began. As for the animals, I wanted Ben to believe in the idea of a parallel universe – in the sense that there is an interdependency of creatures and other living things – and that the story of a human can be told from the perspective of a tree, the story of a country through a worm-hole, or the story of a woman through a bird. When you’re young, the things you remember don’t always come in a linear form, that’s not how the mind works, and there’s something to be said for a representation of occurrences by what you’re fascinated with, which to Ben is animals. And once you represent, say, the death of the brother by a sparrow, it makes the impact of the death less tragic.

Which animal would you identify with?

Oh, man! None that I can think of. I’m just fascinated with them, and I would see myself in many of them at once.

Why did you want to set up a spiritual conflict between Abulu and the local priest Pastor Collins?

You know, Africans are very religious. It’s very rare to find someone who is not. I now live in the Midwest, where empirical secularism is the order of the day, and people are surprised that people still cling to these old forms of belief. But I’ve studied my own people, and they find solace in religion, especially those who are not very well off. And that goes a long way, it gives people a measure of happiness that you wouldn’t find amongst middle-class New Yorkers, for example. But there’s a subtle question too, a commentary that the novel tries to make, of our overdependence on these superstitious things. The mother believes the prophecy could be stopped by prayers. I’m actually arguing for more of a balance: let’s not go too much to secularism, but we have to embrace rational and logical thinking, without completely losing the supernatural. I think the West has gone too far the other way.

Are there any plans for the book to be published in Nigeria, and the rest of Africa?

Yes, we’re talking to a publisher who is very interested, but as I said, because of the almost non-existent reading public, the industry suffers and publishers rely on acclaim from the international community. So if the book does very well in the UK and in Germany – as it has, actually – and in the US, then they will be interested. Because they listen to the BBC, they read the New York Times, and you get more respect at home if people respect you outside.

Most European nations fostered a sense of national identity before sovereign authority, so there was a sense of a shared ancestry, a common good. So they were a nation first, and then they became a state, but the reverse was the case in Africa.”

Why is Yakubu Gowon such a figure of hatred to Ben’s father?

He was the military dictator in 1966 when Nigeria fell into a civil war – which I think was a lost opportunity because that was the moment when Nigerians actually discovered that this whole idea was not our own, this nation was not a creation of ours, and we can actually form other nations. Achebe before he died had been calling for a sovereign national conference. We may actually discover that we could have a sustainable nation as one entity, but we first have to dismantle this thing, and come together and decide on the terms on which it should exist.

Most European nations of the post-World War era first fostered a sense of national identity before sovereign authority, so there was a sense of a shared ancestry, a common good. So they were a nation first, and then they became a state, but the reverse was the case in Africa – in Nigeria, for example, a state was created by the British – and that is why you have state-nations instead of nation-states. It’s why most African nations have failed, and that’s why I think if we can dismantle Nigeria and create it again, it can actually be the first step towards progress.

What have you been writing since you finished this book, and when can we expect the next?

There’s a second novel titled The Falconer, and it does the same thing of trying to tell a story through the characteristics of an animal, this time with a specific focus on a falcon. It’s partly set in the UK, actually, in the mid-nineteenth century, just about when Africans were coming in contact with Britain. I’m a few chapters in, not halfway but almost. I’ll have a first draft by the end of the summer, and then revision might take a few years. Revision is where the actual writing is done.

Chigozie Obioma was born in 1986 in Akure, Nigeria. His short stories have appeared in Virginia Quarterly Review and New Madrid. He was a Fall 2012 OMI Fellow at Ledig House, New York, and recently completed an MFA in Creative Writing at the University of Michigan. The Fishermen is published by ONE, an imprint of Pushkin Press. Read more.

Chigozie Obioma was born in 1986 in Akure, Nigeria. His short stories have appeared in Virginia Quarterly Review and New Madrid. He was a Fall 2012 OMI Fellow at Ledig House, New York, and recently completed an MFA in Creative Writing at the University of Michigan. The Fishermen is published by ONE, an imprint of Pushkin Press. Read more.

chigozieobioma.com

Author portrait © Scott Soderberg

“In his exploration of the mysterious and the murderous, of the terrors that can take hold of the human mind, of the colors of life in Africa, with its vibrant fabrics and its trees laden with fruit, and most of all in his ability to create dramatic tension in this most human of African stories, Chigozie Obioma truly is the heir to Chinua Achebe.”

Fiammetta Rocco, New York Times