Nell Zink takes flight

by Lucy Scholes

Author portrait © Fred Filkorn

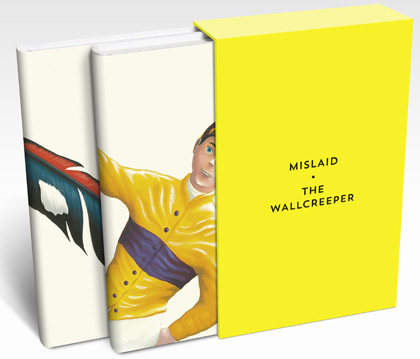

I’d be prepared to put money on the fact that even if you haven’t read either of her novels – The Wallcreeper and Mislaid – you’ve still heard of Nell Zink. Having burst onto the literary scene last autumn with the publication of the former in the US (by the small independent publishing house Dorothy), the fifty-one-year-old American expat who currently lives in the German town of Bad Belzig has been having a moment ever since.

Writing in the New York Times back in October, Robin Romm described Zink’s debut as “a wild thing”, praise that is “the highest compliment it knows” given it’s a story of birdwatching and eco-terrorism. Zink herself was something of a wild writer for many years. Untamed and set apart from any organised literary establishment, she wrote for herself, her partners or select friends. As such, the first thing I want to know when we meet is whether she now feels like she’s living the dream.

“I think it’s important to recognise that it’s very hard for anyone to answer that question because what we all constantly do in this modern world is make a virtue of necessity,” she says, looking at me intently. It’s a bit of an obvious comparison to make, far too obvious I’m sure, but in the flesh she’s a little like a bird herself. She’s slight and elegant in her movements, clearly closely aware of what’s going on around her, and watching the world attentively. And I feel that there’s something flighty there too, like she could spread some invisible wings and fly off at any second.

“You know, actually you’d like to live in a great big Tudor house with fallow deer roaming the lawns,” she continues, “but you’re still really delighted to have found a one-bedroom you can afford, yes? So you say, ‘I love my apartment, it’s so wonderful,’ but you’re making a virtue of necessity. So I was cheerfully writing for myself and a couple of friends, with no thought of publication – only very occasionally, when someone would hammer on me and say, ‘OK, you have to do this now,’ I would send off a little joke enquiry – I mean very occasionally, as in twice in my life, I sent off an enquiry letter to an agent and never got an answer, for legitimate reasons. Like I wouldn’t write the enquiry letter the way they’re supposed to be written and I wouldn’t attach a summary of my work. So I was, I guess, conflicted about it.”

So now she’s, for want of a better term, ‘made it’, how does it feel to have a reading public and to know her work is out there for all to see?

“It’s definitely odd,” she admits. “The first time I wrote anything in the expectation that it was going to be read by more than one or two people was only about a year-and-a-half ago. I wrote a little essay for n+1 online and I was terrified. I felt that everybody in the world was going to read it, and they were all going to hate me. But I’ve since realised that no medium now has the reach of the evening news thirty years ago, nothing reaches everyone. Earlier this year I was asked to write an essay for BuzzFeed and almost as a joke I decided to use it as an opportunity to write about my friend James, a guy I know in Philly. I thought, I’m going to write about how wonderful Jamie is and just wait and see if he ever finds it. BuzzFeed is one of the most popular websites on the planet, right, but who actually reads it, other than 14-year-olds?”

But she’s told him about it since, I ask her; he knows it’s up there?

“Hell, no!” she exclaims with a laugh. “This is research. He’ll never hear about it. In the search results it’ll get lower and lower, until eventually it’s like it never happened. So anyway, when I first started writing for publication I thought people were going to be paying attention, but I’ve since become a lot more relaxed about it because I’ve realised they’re not.”

“Zink is a comic writer par excellence.” New Yorker

But people are paying attention to Zink – reviews of her novels are everywhere, as are interviews with her in major newspapers, not to mention a recent profile in the New Yorker which in itself is a sure sigh she’s made it, doesn’t she agree?

“I literally don’t know,” she says modestly. “It’s like ‘famous for 15 minutes’ has been replaced by ‘famous to 15 people’. I really don’t know.”

I persevere. She’s famous in the literary world, surely she can admit to that, even if in the larger scheme of things it’s a fairly small and somewhat insular domain?

She shrugs her shoulders, clearly still not convinced. “A couple of years ago I went into a Barnes & Noble in the US because I wanted to buy a book of essays by Jonathan Franzen and the clerks didn’t know who he was,” she tells me by way of explanation (apparently the clerk tried to sell Zink The Hunger Games instead, but she wasn’t seduced). And yes, I see her point, if bookshop employees don’t know who Franzen is, there’s little hope for any other writer’s public profile, though thinking about it, I’m inclined to regard this particular encounter as something of an anomaly.

The idea of Zink shopping for Franzen’s work in a Barnes & Noble like the rest of us seems slightly surreal given that their knotty relationship has become the stuff of literary legend. Zink is well aware it’s clickbait too valuable for anyone writing about her to ignore, not that she tries to play down the connection, quite the opposite in fact; she’s completely upfront about how integral he’s been to her success.

“In the story of how I came to be published he’s the Alpha and the Omega, without him there would be no Nell Zink,” she admits, though she is careful to add a qualifier: “but it’s not like he was a huge literary influence or anything.”

Does she even like his work?

“Um, it’s growing on me,” she says diplomatically and we discuss his forthcoming novel Purity for a few minutes, as although radically different works, interestingly it shares a particular character set-up with Zink’s Mislaid – a complete coincidence, she confirms.

The story of how Franzen came to act as Zink’s unofficial agent will go down in literary folklore for years to come. Both keen birders, after reading a New Yorker piece Franzen penned on the subject, Zink wrote to him drawing his attention to the plight of their feathered friends in the Balkans. An old-school pen-pal friendship was struck up and, impressed by her writing, Franzen first encouraged her to pursue her fiction and then set about trying to find a publisher for a novel Zink had written called Sailing Towards the Sunset by Avner Shats.

This is where things get a little complicated. Sailing Towards the Sunset is the title of a novel written by… Avner Shats. She got to know Shats when she was living in Israel with her second husband, Zohar Eitan, an Israeli poet and composer – though, she tells me by way of an aside (a Zink specialty, I quickly learn) apparently he claims he’s not a poet anymore but something else, though what exactly she can’t remember. “He had sort of switched to writing prose poetry and then his most recent project was a novel,” she goes on to explain, “but now he told me he’s abandoned art entirely because since I started to get this reputation and be in the press, girls are interested in him even if he doesn’t do any art himself. Because you know why men do art…” she tails off. “He’s now interesting by virtue of having been with me.”

Marrying a man and using his economic power to finance your freedom could be construed, maybe not as a feminist move… but as an interim solution since the system is just about impossible to change.”

Back to the conversation in hand: she describes Shats as her ‘best pal’ so she obviously wants to read his novel. The problem, however, is that it’s written in Hebrew; and although her understanding of the language is accomplished enough that she can read a paper, the intricacies of the work of an ‘accomplished postmodernist’ elude her. Thus, instead of reading Shats’s novel, Zink re-wrote her own version of it, one that has little to do with the original but instead tells the story of a half-woman, half-seal romantically involved with a Mossad agent. This is just enough detail for me to understand why Franzen didn’t have a particularly easy job on his hands! However, having been captivated by Zink’s particular brand of zany as displayed in both The Wallcreeper and Mislaid, I’m excited to hear that Ecco Press, her American publishers, have made what she describes as ‘noises’ about a potential paperback original edition.

“I say to my editor, ‘Don’t even begin to think I’ve forgotten about it and you can sweep it under the rug,’ but she hasn’t given me a date or anything. I think it would help boost the odds of Avner’s book getting translated though. That’s my secret aim in all of this, and the reason why I repeatedly mention him: I want someone to translate his book.”

This anecdote goes some way to summing up Zink’s attitude to her current fame and acclaim. She’s both unashamedly self-promoting and incredibly altruistic at the same time. One of the very first, and probably the best recommendations of The Wallcreeper I read appeared in a ‘best of the year’ round-up piece published on Salon where Zink did what I assume every other author (both on the list, and in the history of publishing) wants to do, but is too afraid to: she chose her own book. Like much of her writing, she was being both tongue-in-cheek and deadly serious: “Its intellectual level and sense of humor are exquisitely attuned to mine, and I have no trouble filling in the gaps left by its dishonest narrators. The ending delights and surprises me every time, since it was a last-minute decision.” You can practically hear her laughter between the lines. And in the very first paragraph of the BuzzFeed essay mentioned earlier, she has no qualms about reminding her readers that she’s recently been “hailed a genius” and is now earning “serious money” for her fiction.

Without wanting to make sweeping statements, I think it’s rare for women in particular to be this comfortably upfront about their own success, and as such I find Zink’s candour both refreshing and beguiling. But at the same time she’s playing a game, sometimes with the end goal of enhancing someone else’s public profile – whether it’s James from Philly or Avner Shats – sometimes simply for her own or someone else’s entertainment. She famously hurriedly drafted the first few chapters of The Wallcreeper merely for Franzen’s amusement while he was struggling to sell Sailing Towards the Sunset by Avner Shats. And, I learn, even sending it to Dorothy was provocative gameplay.

“I was trying to light a fire under Dalkey Archive Press,” she tells me, explaining that she’d been given the wrong information about the married couple who run Dorothy, and thus assumed (falsely, it turned out) that one of them still worked at Dalkey, the press to which Franzen was then attempting to sell Sailing Towards the Sunset by Avner Shats. “I sent Dorothy The Wallcreeper almost as a joke, it never crossed my mind that they would actually want to publish it,” she explains.

Even acknowledging Franzen’s help, Zink describes the entire process as “a long series of shots in the dark”, and slowly piecing the story together I’m inclined to think that it’s since publication that Franzen’s support has been the most help to her – praise from the likes of him is publicity that money simply can’t buy. It’s the stuff of dreams for any debut novelist.

Dorothy isn’t a feminist publishing project as such, though it does have a female-friendly agenda – books written by women, about women – so it actually turned out to be the perfect fit for The Wallcreeper. The novel is a Bildungsroman that charts the awakening of its narrator Tiffany, a newlywed American expat who follows her pharmaceutical researcher husband Stephen from Philadelphia to Berne then Berlin for his work. It’s a story of female experience but a piece of writing that doesn’t necessarily declare itself as a feminist project. If anything, some readers might be troubled by Tiffany’s complete economic reliance on her husband since for much of the story she doesn’t have a job of her own and refuses to get one. This brings to my mind something I heard Zink say when she appeared on an episode of the podcast The Lit-Up Show – “feminism is something that needs to be financed by someone” – so I ask her if she can elaborate on this with reference to Tiffany’s situation.

“We don’t live after the revolution; it’s just a fact,” she says simply. “As a woman, whatever you’re doing for a living, you’re probably working with guys who are doing the same thing and being paid more for it: that’s life. I’m not saying this as some sort of great ideal, but it’s something worth thinking about: marrying a man and using his economic power to finance your freedom could be construed, maybe not as a feminist move because you’re not trying to change the system, but as an interim solution since the system is just about impossible to change.

“Something that becomes clear towards the end of the book is that the lifestyle Tiffany’s chosen – she’s been reading books, fiction and poetry – is part and parcel of her subjugation. It’s one of the things keeping her from earning money and being an effective activist, and she rejects it.”

I came out of college with a Liberal Arts degree in philosophy qualified to do nothing at all. A lot of philosophy and literature, especially the more intellectually interesting stuff, is so painfully obsolete.”

Tiffany, it should be explained, becomes an eco-terrorist about halfway through the book, and her first act of disassembling a dam rock by rock, stone by stone, becomes a journey of transformation both physical – “I was looking muscular and outdoorsy and more like a birdwatcher’s dream date (the sort of biologist who spends months alone in tern colonies) than ever before” – and emotional: “I had been treating myself as resources to be mined,” she admits on the final page of the novel. “Now I know I am the soil where I grow.”

It’s interesting, not to mention rather unusual, to hear a novelist denigrating the study of the liberal arts, especially someone who studied them herself, but Zink is forthright in her opinion.

“When I went to college I didn’t realise it was possible to go to school and be trained to do interesting work. It was only later that it came to my attention that you could read novels in your spare time and study hydrology and come out of four years of college with the ability to do really interesting stuff with really interesting people, and be paid for it. I came out of college with a Liberal Arts degree in philosophy qualified to do nothing at all. A lot of philosophy and literature, especially the more intellectually interesting stuff that gets talked about there, is so painfully obsolete. Philosophy students will tell you they’re really thrilled and excited about this discovery that it’s our perceptions that create the world we live in. Like a cognitive neuroscientist doesn’t know that?”

But didn’t she experience any exhilaration discovering these ideas for the first time as a student?

“I was excited, yes. It’s just a shame I just didn’t realise that biologists also know this, and they’re the ones doing the cutting-edge research while the humanities are doing the bad armchair versions. Really a lot of the humanities are armchair sociology or armchair cognitive neurosciences – it’s all one big armchair. And I got sucked into that, and I do regret it.”

This gives me pause for thought. Especially considering Zink chose a rather alternative route after college – in that we don’t necessarily expect a Liberal Arts student with a degree in philosophy who ultimately wants to write fiction to turn to bricklaying as a career choice. From manual labour to secretarial work, Zink spent years working a variety of extremely hands-on jobs.

“Oh yes,” she confirms, “but in every one of them I can remember the scene when I stood up and screamed ‘Fuck you’ at a room full of people. It always came sooner or later. Having witnessed myself try to work in teams and do practical things, novelist is a really good job for me.”

She says this with a smile but I can well believe her when she adds, “I am trouble.” This is the impression I got when first reading her novels. They’re clever and funny – extremely funny – but they dare to go there too. The Wallcreeper, for example, is a bold presentation of sex, relationships and male/female power relations. Mislaid, however, is another level of audacity, something that’s Zink’s well aware of.

“I felt very daring when I was writing it because it’s full of things that are wrong,” she confirms.

Set in Virginia – where Zink herself grew up – it tells the story of Peggy Vaillaincourt, a freshman at Stillwater College in the 1960s when the novel opens. Peggy is a lesbian but she’s also attracted to Lee Fleming, an English professor at the school and famous poet who, despite being gay, in turn finds himself drawn to Peggy’s precocious mind and boy-like body: “It was so exciting he couldn’t figure it out. She was androgynous like the boys he liked, but she made him wonder if he liked boys or just had been meeting the wrong kind of girl.”

Needless to say their infatuation is fleeting, though it does last long enough for marriage and two children – a son named Byrdie, and a daughter called Mireille – and the accompanying unhappiness that was bound to follow. Having just about as much as she can take of the monotonous drudgery of life as a faculty wife, Peggy flees the marriage taking Mireille with her, but leaving Byrdie behind with Lee. Determined to not be found by the husband who’s threatened to have her sectioned, she heads into the “murkier depths” of the state, ultimately stealing the birth certificate of a dead black child a couple of years younger than Mireille and henceforth passing them both off as Meg and Karen Brown, an African-American mother and daughter. This, it turns out, is a surprisingly easier deception that one might imagine; “easy as pie” in fact.

“Maybe you have to be from the South to get your head around blond black people,” the narrator explains. “Virginia was settled before slavery began, and it was diverse. There were tawny black people with hazel eyes. Black people with auburn hair, skin like butter, and eyes of deep blue green. Blond, blue-eyed black people resembling a recent chairman of the NAACP. The only way to tell white from colored for purposes of segregation was the one-drop rule: if one of your ancestors was black – ever in the history of the world, all the way back to Noah’s son Ham – so were you.”

For those of us not familiar with the American South of the ’60s and ’70s, such a cultural appropriation might be a hard thing to get our heads around. Or then again, in the light of the recent Rachel Dolezal case, perhaps not.

“When I first saw that story, I was like, ‘Thank god,’ because reviewers [the novel came out in the US in May before Dolezal hit the headlines] had been making fun of me for writing something too far-fetched – a white woman passing herself off as black, they were saying it was from the realm of fantasy. But at the same time, I’m writing about the South in the ’70s, and Dolezal is from Montana by way of Spokane – a place where black people don’t really have a Southern accent, simply because there’s so few of them and there was no segregation so they’ve attended the same schools – so there to say she’s black is not a huge stretch.

“When I was writing Mislaid, I was remembering people I had known when I was young back in Virginia and they’d told me they were black and I was like, ‘You are?’ It’s something that gets swept under the rug, and people who aren’t from the South just aren’t used to it.”

Regardless of the plot’s realism, it’s still a rather ballsy move by a white American author, and I’m keen to know if it was an easier thing to write about removed from America across the pond in Germany?

“It’s hard for me to judge how I would have felt writing those things in the US, but I did feel insulated by an ocean from having social contacts who would shun me or make fun of me at a party for having written it. Maybe if I lived in Brooklyn like everybody else, I would have hesitated to put in the racist joke about Jean-Paul Sartre, but that was a real joke I’d heard. If you’re going to write a book, you shouldn’t flatter yourself that you’re performing a public service, but at the same time I didn’t want to write a book that just anybody could write, I wanted to write a book that was personal, the way an oral history or someone’s account of growing up aspires to give a personal perspective on historical events. If I’d just done a bunch of research and presented a character who was caught up in the movement of black people from A to B based on research in a library, well anyone could do that, they didn’t have to be from the South at all, so my desire there was to make sure it was a book that had a raison d’être, a justification for existing at all: and that was its reliance on my own recollections of what happened.”

It’s perhaps not a plot that will sit comfortably with everyone who reads it, but in many ways Zink has been very careful to avoid accusations of appropriating experience or identities she can’t ever understand. But at the very mention of this she questions my assumptions.

“You don’t know yourself any better than you know anyone else,” she says forcefully. “I don’t know what gives people this weird notion that they’re so well acquainted with themselves; you have to go through years of psychoanalysis to find out what’s going on in your unconscious mind, right? You see yourself interacting with the world, you see yourself in the mirror, you identity yourself with certain groups, you position yourself in society the same way you position a fictional character. I think people really gravely overestimate how much they know about themselves, especially if you limit your interaction with the world, if you have routines and stay in your comfort zone, you don’t know yourself: forget it!”

Having been completely enthralled by both The Wallcreeper and Mislaid, I’m absolutely thrilled to hear that her next novel, Nicotine, is already with her editor. Though a little flabbergasted by the near dismissive way she mentions it: “I drafted something new in March and April, and sold it,” she says in amidst a conversation about something else, so I have to ask for further details. Apparently this kind of speed is normal, “I work in three-week cycles,” she says.

So this is it now, I ask, no more manual labour, no more translation jobs – which, incidentally, she hated – just full-time fiction writing?

“Yes, it’s my job, very definitely. I want to be an author.”

“You are an author!” I reply.

“Yes, I am,” she says, smiling. And as we part ways she’s joking with her publicist about winning prizes and making a fortune in the process, the sort of literary fairy-tale that most writers will only ever dream of, but when it comes to Zink, seems eminently possible.

Nell Zink has worked in the construction, pharmaceutical, and software industries, and is now a translator living in Germany. As a writer, Zink founded an indie rock fanzine in the ’90s, and published short pieces in a variety of outlets. Her novels The Wallcreeper and Mislaid are published in a hardcover box set by Fourth Estate. Read more.

Lucy Scholes is contributing editor at Bookanista and a literary critic and book reviewer for publications including the Daily Beast, the Independent, the Observer, BBC Culture and the TLS. She also teaches courses at Tate Modern and Tate Britain.

@LucyScholes