Sleepwalker

by Jeff Vande Zande

“Shows us what happens when suburbia takes on a rebellious, sometimes eerie and always dangerous life of its own.” Laura Hulthen Thomas

Martin can still hear the way Vickie screamed that night when they’d set the bone. He winces. She was just a little girl, then. Downstairs, pots and pans knock against each other. The cupboard closes. A passing car smears a phantom window over his walls. It leaves behind darkness and the gray outlines of things in the room. Now Vickie must be at least in her late thirties. Forties?

She goes through the silverware drawer. Martin sighs. He doesn’t know why his daughter is home now. He doesn’t want to know.

Sleepwalking. They really didn’t know anything about it. Martin believed it was important not to wake her. Doctors said that there was really no danger in it. Disoriented. Confused. That’s all she would be. She’d come around. They’d also heard that she couldn’t hurt herself. He and Charlotte would lie in bed listening to her downstairs picking up her toys or searching for something. Whispering and giggling over what she might be doing, they held each other. Then one night she pulled the television down on herself and broke her arm.

“Can’t really say how long she’ll do this,” the doctor said. He explained that it usually ended around twelve years old, but it could go longer.

Vickie lay in Charlotte’s arms, already sleeping. Her tiny arm disappeared into the cast. Charlotte asked if there was anything they could do.

“Put up a gate so she can’t get downstairs easily. Move things so she doesn’t trip. Make sure she gets good sleep every night. Naps maybe.” The doctor pulled the curtain back. The E.R. was noisy. Screaming. Crying. Complaining. Talking. Medical babble.

Isn’t there any way to treat it,” Martin had asked, “some pill or something?”

“If it gets really bad, there are short-acting tranquilizers, but hold off on that for now. Just help her take care of that arm. There’s really no quick fix.” He wished them a safe drive home. He left the curtain open.

“Charlotte? Are you awake?” Martin asks, uneasy with his memories.

No answer.

He reaches for the back of her thigh, but can’t find her in the sheets and blankets of the king-sized bed. More cars drone past.

“Why is she home again? I don’t remember her telling us why?”

Martin breathes through his mouth. He stares into the dark ceiling. ‘I shouldn’t have said that to her. I was just… I was angry. But, I shouldn’t have talked like I did.’”

He stares into the blackness above their bed. “Do you remember the first time she came back home? She stayed for a year. Remember? That phone call in the middle of the night. I drove because they said they’d keep her at the hospital until I got there.” He rubs his eyes. “One semester before she was going to finish.”

He pulled open the curtain. Vickie sat on the edge of a hospital bed. At least twenty pounds lighter, she stared at her feet. Stringy hair hanging down. Skinny arms coming out of the thin hospital gown. Harsh fluorescent light.

“Daddy,” she said, “please don’t say anything.” She didn’t look up.

“Why would I say anything? I’ve only been on the road for three hours to take a two-hour trip. I’m damn near night blind, but maybe being on drugs made you forget that.” He tried to stop. “A near overdose. That’s what a doctor was telling me on the phone at midnight about you. So why should I say anything?”

“Daddy, please.”

“Daddy? All of a sudden, daddy? Vickie what… I mean, I wanted to come here someday to see you in a gown, but I was hoping for a graduation gown.”

She raised her hands to her face and convulsed with sobbing. A nurse had to walk her to the car. Then, three hours of silence.

Martin breathes through his mouth. He stares into the dark ceiling. “I shouldn’t have said that to her. I was just… I was angry. But, I shouldn’t have talked like I did.”

He knows what his wife would say. “Vickie was not an easy daughter. So you said things. Still, you let her stay at the house for over a year. That’s what matters.”

“Of course I let her stay. I was angry, but this is home. And, she got help. Remember the meetings?” He reaches again for Charlotte. His hand touches the remote control for the television.

Downstairs, a closet door opens.

“Did you hear that? I think Vickie’s home again. Still sleepwalking. The doctors said she’d outgrow it. So much she never outgrew.” He listens. “Do you know why she’s home, Charlotte? I don’t remember why this time? What does she need? Money? Just a place to stay? It must have been when I went walking after dinner. Is that when she told you why she’s home?”

He pulls the remote from under the sheets. “I’m going to turn this on. Do you mind? I just can’t sleep with her down there making that noise.”

Television light flickers in the room. Martin tries to follow the programs, but can’t. The plots lose him. The punch lines on the late night talk shows aren’t funny. He laughs a few times, but only because he recalls the antics of Johnny Carson’s program. “Now he was funny,” he used to tell Vickie. “These new guys don’t know how to be funny – only filthy. And weird.” He turns off the television, and the room goes black. It lightens slowly.

Downstairs, the den door squeaks on its hinges. He vaguely remembers Vickie being home again for some reason. “I was terrible the last time,” he says, hoping that the television woke Charlotte. “The last time she came home to stay I said terrible things – things a father shouldn’t say.”

“Not every father has Vickie for a daughter. She wasn’t easy,” Charlotte used to say.

“I know, I know… but, still. The next morning she was gone. I remember that night so clearly.”

He had gone downstairs. Vickie was making a sandwich. She made one for him, and then they watched television. They found a channel showing highlights from the Johnny Carson show.

“Now this stuff is funny,” Martin said. He laughed and pointed and looked over at Vickie for her reaction.

“I like Letterman better,” she returned, her mouth full of sandwich.

“Letterman?” Martin hissed. “Throwing pencils around? His stupid faces? That’s not funny.”

She finished her sandwich. “Why are we even watching this? This isn’t even a show. This is a commercial, Dad. They want you to buy their tapes. Do we have to sit here and watch a commercial like it’s a show? Can we see if something else is on?”

Martin was quiet for a moment, but he didn’t change the channel. “You know what else isn’t funny?” he asked. “Throwing your life away isn’t funny,” he answered.

“I’m going to bed.” She stood.

“Not in my house you’re not,” Martin said. “Not with my bread and peanut butter and jam in your mouth, you’re not. You’re going to listen. For once, you’re going to listen.”

She turned towards him and crossed her arms.

He cleared his throat. Then he asked her why she left Roger. She said she didn’t know. He asked if she didn’t think that filing for a divorce was a little rash. She said she didn’t know. He asked her what, if anything, did she know.

“I know this isn’t helping. I know I’d just like to go to bed.”

“Do you think you can just sleep this off? You’re thirty-two years old. You had a house, a husband who took care of you – a husband who was going to help you go back to school. You just walked away from it. Why?”

“I told you I don’t know.”

Martin stared at the television. “You don’t know,” he said. “That boy calls every day. He asks me why. Me. What am I supposed to tell him?”

Vickie uncrossed her arms. She sighed. “I’m just going to go to bed, okay?” She turned around and started towards the stairs.

“I’m going to tell you something,” Martin said.

She stopped, but didn’t turn around.

“I’ve never prayed. But after this – when you had what everyone wants. And now you’re throwing it away… everything, your whole life – like it’s not a gift. I prayed last night. I prayed to something or someone that you start to do something right. I…” He looked up, stopped. “Okay, go ahead. Run up to your room! Smoke a cigarette and blow the smoke out your window like you did when you were a teenager under this roof. That will make everything better. A little girl. That’s all you’ll ever be!” He was yelling up the stairs after her until her door slammed.

“When I came to bed that night you didn’t say anything,” he says to Charlotte. Then he waits. “You were kind, but I know I was wrong. I wasn’t a good father. The next morning she was gone. Not even a note.”

“Vickie was never an easy daughter,” Charlotte used to say. “You do what you can. You leave the door open. What else can you do?”

“I was a terrible father,” he says.

He’d said it before, but Charlotte always reminded him that even after that last time Vickie called three days later. He begged her to come back, and she did.

“But still,” he says, “a father doesn’t say such things. Such venom.”

‘Charlotte, did you hear that? There’s someone in the house?’ He remembers something dimly. ‘Maybe it’s Vickie. She’s home, isn’t she? She came home again. I think she’s sleepwalking.'”

He reaches around. His hand touches upon the television remote control. He turns it on. He finds nothing he can follow. He hits the button again. Darkness.

“Charlotte? Charlotte? Do you think I was a terrible father? I said such things. I have my father’s mouth. I just think that I pushed her away – that it’s my fault that she turned out this way. Will she ever come around?”

He listens. Nothing. He decides he’ll let his wife sleep.

A drawer opens and then closes downstairs.

Martin sits up. “Charlotte, did you hear that? There’s someone in the house?” He remembers something dimly. “Maybe it’s Vickie. She’s home, isn’t she? She came home again.”

He listens. The house pings and pops in the walls.

“I think she’s sleepwalking. She never outgrew it. Remember, like the doctor said?” He listens. “She’s so quiet down there.” He sits up and puts his feet on the floor. “Do you remember the television? Her little arm?” He listens again. “Why is she here? It’s so quiet downstairs now. What’s she doing?”

He stands up. “I’m going to check on her,” he whispers over the bed.

The stairs creak under his feet. He thinks he hears Charlotte coming behind him, but he has to concentrate on the steps to keep his balance. He stops on the landing and can hear Vickie talking in the kitchen.

“Yeah, fine I guess,” she says. “Fine as can be.”

She pauses.

“Sometimes to me, but it’s in and out.” She’s quiet for a moment. “Yeah. More to himself, really. Or, I guess to her. That’s what it sounds like. Like he thinks she’s still here.”

Martin smiles. “Do you hear her? Sleepwalking. Remember the doctor talking about the talking – the sleep talk babble?” He turns, but Charlotte is not on the stairs. He will tell her in the morning. He takes the last few steps.

He moves towards the corner. “About three weeks already,” Vickie says. Kitchen light shines off a wall in the dining room. “I’ll stay until whenever. I just want him to be in his own house for as long as possible.”

Martin grins, snorting a tiny laugh through his nose. Beginning to turn the corner, he stops. He’s not sure he’s ready to know why his daughter is home. He remembers something dark. Then he forgets and turns into the light.

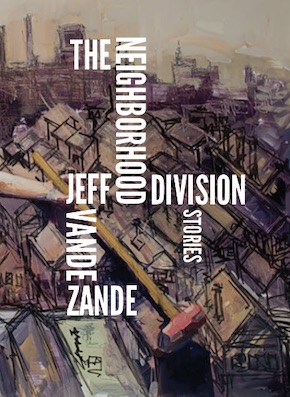

From the collection The Neighborhood Division (Whistling Shade Press)

Jeff Vande Zande teaches fiction writing and film at Delta College in Michigan and writes poetry, fiction and screenplays. His other books include the novels Landscape with Fragmented Figures, American Poet (both Bottom Dog Press) and Detroit Muscle (Whistling Shade Press). American Poet won a Michigan Notable Book Award from the Library of Michigan.

Jeff Vande Zande teaches fiction writing and film at Delta College in Michigan and writes poetry, fiction and screenplays. His other books include the novels Landscape with Fragmented Figures, American Poet (both Bottom Dog Press) and Detroit Muscle (Whistling Shade Press). American Poet won a Michigan Notable Book Award from the Library of Michigan.

Read more

Buy from bookdepository.com

Buy the Kindle eBook

authorjeffvandezande.blogspot.com

@jcvandez

Author portrait © Luke Goodrow

‘Sleepwalker’ was adapted by Jeff Vande Zande for a short film directed by Michael Randolph.

Watch on Vimeo