Many a woman scorned

by Karin Salvalaggio

“Well written, pacy, and full of twists and turns.” Lucy Scholes, Independent

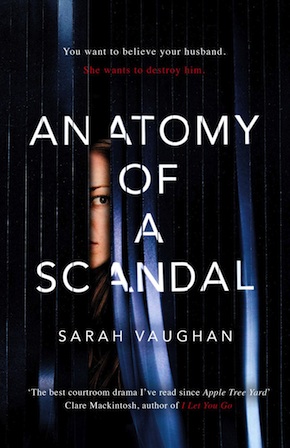

If Sarah Vaughan possessed a secret superpower I’d hazard to guess that it was precognition. The storyline of her latest novel Anatomy of a Scandal could have been plucked from today’s newspaper headlines. To label the work as a political thriller would be missing the point, as it is so much more than that. Deftly written, the novel bridges past and present; questions of guilt and innocence; loyalty and collusion; and issues of consent and sexual assault along with all the grey spaces in between. Kate is a successful barrister who specialises in prosecuting sexual assault cases. A woman with secrets, she is driven by more than justice. Sophie is the beautiful wife of an ambitious politician named James. She’s put her Oxford education and any dreams she may have had for herself aside to look after her husband, children and home. James is a junior minister in government who is one of the Prime Minister’s closest and oldest friends. He is also the man who stands accused. Sophie wants to believe him and Kate wants to destroy him. The stakes couldn’t be higher. Anatomy of a Scandal is a novel that holds a mirror up to our troubled times and finds us all guilty of varying degrees of complicity.

Harvey Weinstein was once a formidable force in Hollywood. A big man in more ways than one, he wasn’t the first to be exposed, but it was his downfall that set off a cascade of revelations that have left all of us feeling bruised and bewildered. A long list of celebrities, broadcasters, musicians, politicians, restaurateurs and company executives have recently been accused of sexual assault. Revelations have slowed, but throughout the latter part of 2017 lurid tales of unwanted sexual advances, sexual harassment and rape dropped out of the internet like bombs on a daily basis. Kevin Spacey. Boom! Lewis CK. Boom! Al Franken. Boom! Michael Fallon. Boom! Damien Green. Boom! Dustin Hoffman. Boom! A middle-aged white male trending on Twitter once sparked worries of an untimely death, but those days of innocence have passed. Our eyes are open and we do not like what we see. Cue the hostile reckoning. Uma Thurman is pissed, Salma Hayek has gone public, TIME magazine has featured those that have broken the silence on their cover, Rose McGowan has been vindicated, and the rest of us are thinking if they can scream we can scream too.

And boy did we scream.

I’d like to think that 2017 will go down in history as the year women finally woke up. The shock election of the notorious ‘pussy grabber’ Donald Trump lit the match, righteous anger provided the fuel, and hashtags kept the engines running on social media. Within 24 hours of Trump’s inauguration the world witnessed the largest protest march in America’s history. Women, men and children from all walks of life donned pussy hats and placards and took to the streets of not just America, but cities all over the world. And it didn’t end there. Women have been busy organising themselves thoughtfully and collectively in places of work, worship and play. We refuse to be polite and we refuse to be patient. We want change and we want it now.

To block, or unblock, that is the question.

To block, or unblock, that is the question.

Much has been written and broadcast about those accused of committing acts of sexual assault and the women and men who have accused them. Everyone on social media seems to have an opinion, informed or otherwise. The battle lines have been drawn – in some cases quite harshly. You’re either with us or against us. It’s a confusing time and soundbites, Twitter posts and pithy editorial pieces fail to do the subject justice. There is simply no way to make a real connection with those on either side of the argument in a world that lacks nuance. How do we combat rape culture if we refuse to communicate with people who are entrenched in its dogma? Where is the empathy for the victim? And where is the courtroom? Making accusations on social media isn’t sustainable. At some point someone has to go to trial.

Sarah Vaughan and I first met when we joined The Prime Writers, a loose affiliation of authors who support each other’s work on and offline. I soon learned that Sarah possesses the two tools all great writers cannot live without – a legendary work ethic and a meticulous eye for detail. The fact that she also writes beautifully seals the deal. We took some time to share our thoughts on Anatomy of a Scandal and the present state of sexual politics. I gave her some tricky questions and she was game enough to answer them.

KS: Rape culture is defined as ‘a society or environment whose prevailing social attitudes have the effect of normalising or trivialising sexual assault and abuse’. Anatomy of a Scandal highlights the pervasiveness of rape culture in our society today without you once using the phrase. Readers do not always warm to books that take on social issues, as more often than not the storytelling suffers. Happily, you found the right balance. This may seem effortless to the reader but I know from personal experience how difficult it is to achieve. Did you set out to take on rape culture when you started writing Anatomy of a Scandal or did that evolve with time?

I didn’t want my pre-teen daughter to experience the same difficulties in navigating sexual politics and future relationships that our generation has. But this was always a novel, not a polemic.”

SV: I knew from the very start that Anatomy of a Scandal would focus on an alleged rape by a charismatic, entitled and, crucially, attractive politician who’d been having an affair with his parliamentary researcher, and I dreamed up the idea after having an animated discussion with two friends about the rape trial of a footballer, so rape and the question of consent were to the forefront of my mind. I was also conscious of what we’re now calling our #MeToo moments – and of how I didn’t want my pre-teen daughter to experience the same difficulties in navigating sexual politics and future relationships that our generation has. But this was always a novel, not a polemic. It was the characters and how they deal with the trial and its aftermath that were important. I came up with the idea in late 2013 so the issue hadn’t yet erupted into the public consciousness in the dramatic way it has post-Weinstein. But with the discussion of the footballer rapist – whose conviction has since been overturned on appeal – and the judgements made about the young woman in the case, it did feel as if it was brewing.

The MeToo hashtag is all over social media, Uma Thurman is angry (but won’t tell us why), men who once dominated the entertainment industry are, metaphorically speaking, falling on their own swords, and there is also a bit of fallout in the heart of Westminster where much of your novel is set. Historically speaking, conviction rates for sexual assault against women are abysmally low both in the UK and US. In the wake of the Harvey Weinstein scandal we’re seeing a ‘hostile correction’ being played out in social media. Men are being forced from their positions of power, not by the courts of justice but by the courts of public opinion. We’re living in a time when public shaming has become the weapon of choice. What are your thoughts on this confrontational reckoning? Is it, as many feel, the manifestation of frustration women have felt for years? We do after all have Exhibit A sitting in the White House at this very moment. If an audiotape of him bragging about sexually assaulting women wasn’t enough to stop him getting to the top, what chance do we really have of moving the conversation forward?

I’ve read that the timing of Weinstein being outed and the subsequent #MeToo outpouring was prompted by the catalyst of Trump being elected. Women felt this collective shock and anger that a man who’d bragged of being able to “grab ’em by the pussy” was now the most powerful in the world. I think there’s very much an element of that here, in the same way that the Jimmy Savile case, and our collective guilt at not recognising he serially abused children, has led to a sea change in how we now treat child-abuse victims. Perhaps this ‘hostile correction’ – this unflinching calling-out of public figures in particular for their sexual misconduct – is partly motivated by our desire to try to redress what happened with the election of the US president.

Personally I found it very hard to explain to my then 11-year-old daughter that Trump had been elected when I’d had to explain his ‘locker-room banter’ comments just a month earlier. “But how could they vote for him if he speaks like that about women?” she asked, baffled, as she clocked yet another example of adult fallibility.

But this isn’t just a reaction to the election of Trump. It’s clearly the manifestation of years of frustration – and anger. The #MeToo campaign has brought back lots of uneasy memories for me, as well as frustration that from my mid-teens onwards I’d internalised the idea that harassment -– from catcalling to cars mounting pavements behind me, to men flashing and worse in parks or on public transport – was just something that happened to young women and girls.

That’s not to say that some of the trial by social media hasn’t made me uneasy. There’s something very unsettling about a mob mentality. Nor that we shouldn’t recognise that there are degrees of harassment: it should go without saying that a clumsy pass can be just that; and that an unwanted knee-brushing is at the other end of the continuum from rape. What’s so critical, and so apparent in the bulk of allegations emerging from Westminster, is that power – and an abuse of it – is the key element. It’s older men in positions of authority harassing younger staff members, or much younger journalists. And now those younger women – and some men – are speaking out.

You tell the story from three points of view. Kate is a barrister living in London, Sophie is a married mother of two and James, her husband, is a junior minister who is a lifelong friend of the Prime Minister. I don’t believe I’m giving much of the plot away when I say their worlds collide. I’ve always been as fascinated with character arcs as I am with storylines. Though Kate’s story is fascinating and she clearly evolves throughout the novel, the dramatic part of her transformation pre-dates the present day. James on the other hand is so blind to his shortcoming that he hardly changes at all. It is Sophie’s character that interests me the most as she’s the one who travels furthest. It was fascinating to see how you handled this. Though there were quiet moments of ‘unravelling’, she never once loses her composure in public despite her husband’s very public shaming. It would have been so easy to write a different ending to her story, but you chose not to. Which character did you find the most challenging to write and why?

I’m not very good at repressing my emotions like Sophie. The challenge was in trying to convey this apparently impervious exterior while revealing her internal life to generate sympathy.”

I think you’ve answered that question for me! I found Sophie the most challenging because of all the women in the novel she was the least like me. I felt far more immediate sympathy for Kate, who I wrote in the first person: I’ve always been drawn to damaged characters and not only is Kate an outsider, like many writers, but she is bright and in some ways fearless. It was a complete joy to create an outwardly successful woman and I’d love to return to her one day. But Sophie’s steadfast loyalty and willingness to be a good little wife felt alien in many ways – and almost anachronistic. As a married mother-of-two whose own parents divorced, I could very much understand that desire to maintain her tight family unit, even if I didn’t share the extent to which she was willing to do so. In writing her, I was very conscious of needing to convey that she had narrowed her options – and that her confidence had diminished as her relationship continued. She’d given up her career when she had their first child, Emily; lived where James’s career dictated; prioritised his needs; subsumed herself in dedicating herself to her family and her man. I’m not very good at repressing my emotions like Sophie, but I could clearly imagine a restrained, upper-middle-class woman, who knew she was on public display and for whom any public outpouring would be shameful. The challenge was in trying to convey this apparently impervious exterior while revealing her internal life to generate sympathy.

There was recently a brilliant piece by Amanda Hess in the New York Times in which she argues quite forcefully that it’s time to do away with the idea that an artist’s work should be seen separately from their misdeeds, or as she calls it ‘biography’. While Anatomy of a Scandal is set in the world of politics it is easy enough to see the parallels. We may love Bill Clinton for all that he has done for the liberal causes we truly believe in, but he is also a man who preyed on a young intern, and for the most part got away with it. Is it ever right to cherry-pick? If we’re going to call out Trump’s behaviour surely we have call out Clinton’s.

There was recently a brilliant piece by Amanda Hess in the New York Times in which she argues quite forcefully that it’s time to do away with the idea that an artist’s work should be seen separately from their misdeeds, or as she calls it ‘biography’. While Anatomy of a Scandal is set in the world of politics it is easy enough to see the parallels. We may love Bill Clinton for all that he has done for the liberal causes we truly believe in, but he is also a man who preyed on a young intern, and for the most part got away with it. Is it ever right to cherry-pick? If we’re going to call out Trump’s behaviour surely we have call out Clinton’s.

I find Clinton hugely problematic. I think we definitely do make concessions if we’re left-leaning, and if we’re honest because he was so charismatic. As a very junior reporter, I once chatted to an Oxford don who’d met him not long before the Lewinsky story had broken. This academic was straight, he told me, “and happily married for 30 years, but I’d sleep with him if he asked me. I’ve never seen such charisma,” he only half-joked.

Which doesn’t, of course, excuse the former president’s behaviour. Monica Lewinsky has said the relationship was consensual, but she was a 22-year-old intern and he the 49-year-old President and this wasn’t just a knee-brushing. He might have claimed not to have had “sexual relations with that woman” but most of us, in the UK at least, would think of oral sex as sex. If this happened in the current climate, I think those calling out Weinstein and Spacey – let alone our own MPs for more relatively minor examples of sexual misconduct – would, quite rightly, be more judgemental.

Believe it or not, I found an interesting parallel in structure between Anatomy of a Scandal and Cormac McCarthy’s No Country for Old Men, a novel where the three main characters don’t once come face to face. Though your characters interact in flashback, they are for the most part isolated from each other for much of the present day. Barring a couple of brief interactions between Sophie and James they barely speak, and when we see the three of them together in court James is behind a screen, Kate is behind a desk and Sophie is hiding out up in the public gallery. They are three characters inextricably linked yet very much fighting their own battles. Was this something you purposefully set out to do or did the structure evolve organically?

I think this evolved organically. There are a few scenes between James and Sophie – at the start and then some pretty key ones after the trial – and there is the court interaction between Kate and James, but I suppose each character spends time locked in their own battle, and both the women have chapters when they’re alone with their own thoughts. I did think about a final confrontation between Kate and Sophie, but I clearly wanted to keep them in their discrete worlds. They aren’t women who would be natural soulmates and they approach this crisis involving James with different agendas. I can’t imagine that there would be any easy meeting point.

Lisa Levy’s piece in LitHub ‘On Rape Culture in Crime Fiction: Why we can’t seem to stop reading (and writing) about violence and abuse against women’ is an unflinching criticism of crime fiction’s often abysmal treatment of women. We, as crime writers, certainly have the opportunity to reset the balance in our work but many of us instead choose not to. You took great care in writing scenes that many women will relate to on a deeply personal level. There was real empathy and I never once felt you crossed the line. In one scene an act of violence is recounted in public court and in another inside a young woman’s head as she tries to make sense of what has just happened to her. Both are devastating. Do you feel we have a responsibility as writers to be more responsible about how we portray sexual violence?

Absolutely. Writing this was a huge leap of faith compared to my previous two women’s fiction novels, although I’d argue that both of them touch on abuse, the second quite explicitly, and I knew I didn’t want to write anything that felt sensationalist, titillating or gratuitous: I’ve found very graphic descriptions of sexual violence disturbing and I didn’t want to cross that line. But at the same time, I couldn’t dress this up or veer away from the horror of what happens. To do so would minimise what happens to my characters and the experience of rape victims in real life.

The whole novel explores how meaning emerges in the things that aren’t said – and it’s pretty evident what the meaning is here.”

Before I started writing, I watched a criminal barrister prosecute in a sexual offences case at the Old Bailey, and saw the opening of a rape case at my local Crown Court. I then contacted the barrister I’d seen in London and shadowed her throughout a rape trial. As a former Guardian journalist who’s done a lot of court reporting, I took very detailed shorthand notes of the way in which she led the alleged victims through their evidence, and was surprised at the detail of her examination. Olivia’s evidence very much mirrors what I heard in court. Of course I’ve fictionalised it, cut out the repetitions and legal argument, and put her in very different scenarios. But the drama inherent in the examination by both prosecuting and defence barristers, and the level of brutal, anatomical detail is just what you’d see in court.

I thought that this was incredibly important because Olivia, the parliamentary researcher whom James is accused of raping, isn’t given her own point of view. The court scenes are seen through Kate’s first-person narration, and so this is the only ‘voice’ Olivia has. Court currently grants alleged victims anonymity – there are reporting restrictions that forbid their names being used, and complainants can give evidence either via video link or behind a screen, so that they don’t see the man they’re accusing – and, as in real life, the tabloids make certain judgements about Olivia. So I hoped that her story would seem more powerful if it was heard as dialogue in court.

As for the act being told in a character’s head, without wanting to create spoilers, I thought this was the way in which this character would try to deal with it. The whole novel explores how meaning emerges in the things that aren’t said – and it’s pretty evident what the meaning is here. The character alludes to a Victorian novel, Tess of the d’Urbevilles, in which Hardy writes: “But where… was Tess’s guardian angel?” She doesn’t cite the quote, but anyone reading who’d read it would pick up on it. Hopefully it’s a case of less is more.

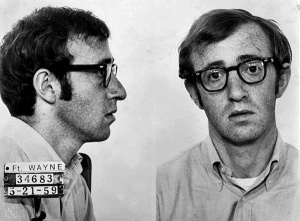

Take the Money and Run, 1969. ABC Films/Wikimedia Commons” width=”360″ height=”266″>Claire Dederer’s ‘What Do We Do with the Art of Monstrous Men?’ in the The Paris Review highlights the moral dilemma many of us now find ourselves in. Roman Polanski, Woody Allen and Bill Cosby, to name but a few, stand accused, and in some case convicted, of sexual assault. As Dederer bluntly states, “They are monster geniuses, and I don’t know what to do about them.” Is it right, as some argue, to keep the work separate from the biography of the creator, or does that biography disrupt the work in ways that render it impossible for us to watch without constantly looking for signs of the creator’s monstrosity? And what of the female artists who stand accused of being monstrous? Dederer writes, “This is what female monstrousness looks like: abandoning the kids. Always. The female monster is Doris Lessing leaving her children behind to go live the writer’s life in London. The female monster is Sylvia Plath… She dreamed of eating men like air, but what was truly monstrous was simply leaving her children motherless.” As a divorced mother-of-two, I am painfully aware of what it feels like to be seen as monstrous. Writing novels requires a degree of selfishness that stands in direct opposition to expectations of motherhood. If we’re not feeling guilty about neglecting our children, we’re feeling guilty about neglecting our work. In my case the spouse is out of the equation, which I suppose is fortunate on one level, as that is guilt I can do without, but I am curious as to how other female writers manage to ignore ‘the pram in the hall’ so they might harness their inner ‘art monster’.

Take the Money and Run, 1969. ABC Films/Wikimedia Commons” width=”360″ height=”266″>Claire Dederer’s ‘What Do We Do with the Art of Monstrous Men?’ in the The Paris Review highlights the moral dilemma many of us now find ourselves in. Roman Polanski, Woody Allen and Bill Cosby, to name but a few, stand accused, and in some case convicted, of sexual assault. As Dederer bluntly states, “They are monster geniuses, and I don’t know what to do about them.” Is it right, as some argue, to keep the work separate from the biography of the creator, or does that biography disrupt the work in ways that render it impossible for us to watch without constantly looking for signs of the creator’s monstrosity? And what of the female artists who stand accused of being monstrous? Dederer writes, “This is what female monstrousness looks like: abandoning the kids. Always. The female monster is Doris Lessing leaving her children behind to go live the writer’s life in London. The female monster is Sylvia Plath… She dreamed of eating men like air, but what was truly monstrous was simply leaving her children motherless.” As a divorced mother-of-two, I am painfully aware of what it feels like to be seen as monstrous. Writing novels requires a degree of selfishness that stands in direct opposition to expectations of motherhood. If we’re not feeling guilty about neglecting our children, we’re feeling guilty about neglecting our work. In my case the spouse is out of the equation, which I suppose is fortunate on one level, as that is guilt I can do without, but I am curious as to how other female writers manage to ignore ‘the pram in the hall’ so they might harness their inner ‘art monster’.

I’m having to learn to be more selfish in carving out more writing time. I largely write when my children, aged 9 and 12, are at school. So I’m there for my youngest at the school gate from 3.30 (or 4.30 when he does sport three days a week). I’ll then do emails – or, if on deadline, write – once they’re in bed. But, because I have been asked to do more events to promote Anatomy, they’ve had to become used to me being away. I feel guilty about that, but at the same time conscious that it’s good for them to see me succeed in my field, as well as my husband in his. In February they’re all coming to Barcelona for the Spanish launch and I think that will be very positive. Certainly seeing me at the Paris launch of my first novel, when they were 6 and 9, was the moment when they really understood what I did.

At the risk of trotting out clichés, it does feel like a constant juggle to balance both writing well and keeping my children happy. I feel like I’m physically very much around for them: ferrying them to after-school athletics and football; cooking meals from scratch; putting their needs first. But when I’m preoccupied with a novel, and particularly in the couple of months leading up to deadline, I’m not always in the present. I can feel distracted. I’ve also experienced insomnia due to fretting about how Anatomy of a Scandal will be received, so I know I’ve been grumpier. (I’m not great on four hours sleep.) Obviously I then feel guilt about this, but I’m convinced they benefit from having an engaged, intellectually stimulated mother, as well as us benefitting financially.

If I’m completely honest, I do crave headspace at times: not away from my children’s emotional needs but just from the admin that clutters family life. The demands for school trip money and forms for concerts, for creating crafts for school fairs; for organising childcare or complicated lift arrangements to and from clubs; for taking the car to be repaired.

Perhaps I’ll write sharper once they’ve left home, but there’s no way in which I would wish away their childhood. Having children is the best thing that’s ever happened to me, while ‘the pram in the hall’ gives me a necessary focus. It also makes me rein in my perfectionism, which is no bad thing.

I didn’t start writing fiction until my children were 7 and 4 so motherhood, and the intensity of emotion that it has provoked in me, has always been at the heart of my writing. And, had I not had kids, the practical impossibility of being a lobby journalist wouldn’t have arisen. I might still be reporting on politics. So, really, I have them to thank for becoming a novelist.

Sarah Vaughan is a novelist and journalist based in Cambridge. Her first novel, The Art of Baking Blind, was published in 2014 by Hodder in the UK, and in nine other countries. The Farm at the Edge of the World followed in 2016, and in 2017 became a bestseller in France. Anatomy of a Scandal is published by Simon & Schuster in the UK and Atria/Emily Bestler Books in the US, and translated into 17 other languages.

Sarah Vaughan is a novelist and journalist based in Cambridge. Her first novel, The Art of Baking Blind, was published in 2014 by Hodder in the UK, and in nine other countries. The Farm at the Edge of the World followed in 2016, and in 2017 became a bestseller in France. Anatomy of a Scandal is published by Simon & Schuster in the UK and Atria/Emily Bestler Books in the US, and translated into 17 other languages.

Read more

sarahvaughanauthor.com

@SVaughanAuthor

Author portrait © Phil Mynott

Karin Salvalaggio is the author of the Macy Greeley mystery novels Bone Dust White, Burnt River, Walleye Junction and Silent Rain and a contributing editor at Bookanista. She recently completed a new standalone thriller set in West London.

karinsalvalaggio.com

@KarinSalvala