A kind of truce

by Elsa Drucaroff

It’s the middle of the night on a residential street. Rodolfo Walsh leaves his house and heads to a nearby bar located at the last stop of one of the city bus lines. At this hour, it’s full of regulars: cabbies and bus drivers.

Since the payphone is all the way in back – right before the staircase to the basement, next to the storage room and the filthy bathrooms – there is a certain measure of privacy. Walsh deposits a token. He’s rattled, but trying hard not to let it show. He dials a number from memory.

In a downtown apartment, the phone rings. A woman about forty-five years old, half-asleep in bed, reaches out blindly for the phone on the nightstand. “Hello.” She too was once a young mother. But the passage of time shows more on her face than his.

“Marta, it’s me.”

“What happened to Vicki!” This wasn’t a question, but a cry of certainty and hopelessness.

“Radio Colonia said there was a confrontation with the Army, and they gave her name as a possible victim.” Rodolfo is whispering because he doesn’t want to be heard, but perhaps he also can’t bring himself to speak any louder.

“What happened to Vicki?” Marta says, still confused.

“The radio gave her name as a possible victim in a—”

“What happened to Vicki! Please, Rodolfo, just tell me what happened!”

He takes a deep breath and says, his voice gravelly, “They killed her, Marta! I think they killed her!” His voice is louder now, but he doesn’t shout. Because he can’t.

Marta is speechless. What she has just heard is slowly registering. On the other end of the line, Walsh isn’t moving a muscle. He’s falling apart. Since she says nothing, he decides to speak. “Marta, listen to me. It’s still unconfirmed. I want you to go to—”

“Shut up.”

“Just, listen—”

She screams, “You killed her, you sonofabitch!” and slams the phone down.

*

Meanwhile, a thickset man in his living room, Colonel König, is sitting in pajamas at the bar, watching the shadows change with the on-and-off glow of the Coca-Cola sign. He stretches to flick on a low lamp next to a glass curio case with precious antiques, his gaze focused on an exquisite eighteenth-century figurine with a broken arm, a small porcelain shepherdess.

König goes over to the bar and pours himself a whisky. He drinks, lost in thought, then turns off the light, leaving the room dark, illuminated alternately by the blinking red and white sign, then only the glint of his ice cubes. During a brief interval of light, he leans toward the display case and opens it. With surprising care his fat hands pick up the shepherdess. He observes it closely, gravely, then sets it back in its place. The man has grown bulky, but cannot yet be called elderly. The ice tinkles on its way down to his mouth. He draws his eyebrows together as he savors his drink, brooding darkly. Alone, inescapably alone, in his enormous, empty living room.

*

König strides across the street toward Café La Paz, on Corrientes and Montevideo. His insomnia has kept him up until all hours, but he woke up bright and early anyway, although he had to wait before putting into effect the plan he’d sketched out at dawn. As he’s walking up to the pool room on the second floor, he thinks it’s probably going to be empty and he’s wasting his time. The clock says eleven. A young guy practicing alone, with his back to him, is bent over the table with his cue. A couple of retirees are playing chess nearby. König heads their way. “Morning, fellas. Pardon the interruption, do you two come here often?”

The men eye him somewhat distrustfully. One of them stops the clock. “I suppose you could say that,” he answers vaguely. “Why?”

“I’m looking for a friend who used to play chess here, Rodolfo Walsh. I’d like to leave him a message. You know if he comes around here much?”

At the mention of Rodolfo’s name, the youngster playing pool turns ever so slightly, in a careful and controlled fashion. König doesn’t notice because he has his back to him. Neither do the chess players. One of them shakes his head, but it seems to ring a bell for the other one. “Rodolfo – the journalist, right? Nope, we haven’t seen him around here in a looong time! He used to come by at night, but that had to be about two years ago. Nah, he doesn’t come in here anymore—”

“Well, bad luck, I guess. Thanks anyway.”

König heads towards the stairs. The pool player’s eyes follow him out. It’s Pablo. Abruptly, König turns around, as if he could sense someone was watching. Pablo averts his gaze immediately and pretends to be concentrating on his next move as König walks back over to the chess players, takes out a card, leans on the table to write something, and says in a voice that’s almost too loud, “Look, just in case, if you happen to see him, would you give him this card for me? Tell him it’s from an old buddy.”

“Okay, but I don’t think he’s coming back.”

“Well, if not, just throw it away and don’t worry about it.” The colonel marches out of the room, and the old men resume their game. They’re not very much interested in the matter. But Pablo is. He’s turned around, and now he seems to be watching them play. Although if you were to really look at his eyes, you’d see that’s not what he’s doing. There’s the card, resting quietly on the edge of the table.

Why don’t you come over to my place? It’s the most secure spot I can think of. I’ve got some good whisky, too. We’ll just talk. And as soon as we’re done talking, we can be enemies again.”

A few hours later the telephone rings in König’s apartment.

“I heard you were looking for me. Something about a broken two-hundred-year-old doll. A shepherdess. Derby porcelain.”

There’s a moment of silence.

“Yes, I’ve been looking for you,” the colonel confirms. “Can you come by?”

“What for?”

“I can find the missing arm. Well, maybe.”

“Not sure if I have the time right now, Colonel—”

“Just listen to me, man, don’t be so thick. I can help. You of all people should know the value of the shepherdess, it’s priceless.”

Silence on the other end of the line. Then a clipped sigh. “Fine. I’ll meet you sometime between three and four, on Florida Street between Rivadavia and San Martín Plaza. You just walk around. I’ll find you.”

*

There’s a crowd on Florida Street. It’s banking hours, and everyone’s still at work. Rodolfo Walsh catches up with König, and they walk side by side.

“Took you long enough. I was starting to lose my patience,” says König.

“You’re the one who wanted to see me.”

“I was only thinking about your daughter. I mean, I was wondering if it was really your daughter… My sincere condolences, Walsh, really, I mean it.”

For a brief moment, Rodolfo’s face contorts violently as if something got in his eyes and was burning acutely, as if an insect had suddenly flown into his face. It only lasts a second, then he shakes his head, and his face once again goes blank, hard. “So you’re saying she’s dead,” he says.

“I think so. But don’t misunderstand me, I hope she’s dead. You and I both know why. But – the truth is I have no idea if she’s dead or alive. These days, not even I know what’s going on.”

Walsh doesn’t respond. They walk in silence.

“Listen, man,” König says all of a sudden, “Why don’t you come over to my place? It’s the most secure spot I can think of. I’ve got some good whisky, too. How about a truce? Look – I’m raising the white flag, you’ve got my word of honor. We’ll just talk. And as soon as we’re done talking, we can be enemies again.”

Walsh hesitates.

“Word of honor, Walsh,” König says without guile.

Walsh stops walking and turns to him, staring hard. The colonel holds his gaze and smiles sadly.

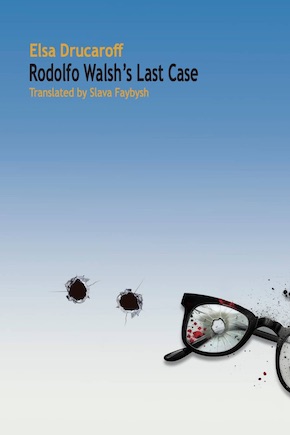

from Rodolfo Walsh’s Last Case, translated by Slava Faybysh (Corylus Books, £9.99)

—

Elsa Drucaroff was born and raised in Buenos Aires. She holds a PhD in Social Sciences and is a professor of literature at the University of Buenos Aires, where she has taught for several decades. She is the author of four novels and two short story collections. She is also a prolific essayist and has published numerous articles on topics such as Argentine literature, literary criticism and feminism. Rodolfo Walsh’s Last Case, her first full-length novel to be translated into English, is published in paperback and eBook by Corylus Books.

Read more

@Elsa_Drucaroff

@CorylusB

Author photo by Héctor Piastri

Slava Faybysh is a translator based in Chicago. His translation of Elsa Drucaroff’s short story ‘Lili in Her Forest’ was published in New England Review in 2023. Other short translations have appeared in the Southern Review, The Common and elsewhere. He also translated Leopoldo Bonafulla’s anarchist memoir, The July Revolution: Barcelona 1909.

@slavabob8