Enchanted by the mystery of books

by Mika Provata-Carlone Ana Pérez Galván, the tranquil force behind Hispabooks, has an unwavering dream: to publish new writing from every corner of Spain in English translation, and to change readers’ perceptions of Spanish literature as eternally oscillating between the two monumental poles of Cervantes and Lorca; to revise our view of Spain as being only the realistic figment of Hemingway’s or Orwell’s imagination. Ana belongs to a very precious minority of publishers whose relationship with their trade, their art and its products is as tactile and intimate as it is philosophical, vocational and visionary. For Ana, who trained as a journalist, publishing is a gesture of love, understanding and humanity, the means to sustain a fragile and brittle national and global community. Books must make a difference, they must have narrative and cultural resonance, and the bulimic fascination with new releases, in her view, undermines our intellectual culture and publishing ethos. Her passion for words, for language, for local voices (she speaks beautifully), and the private mystery of individual lives are evinced in every novel on the Hispabooks list, and emanate powerfully in her presence. Ana’s gentle resolve conceals a sharp intelligence, a very fine instinct for meaning and for the craftsmanship of beauty, as well as a very shrewd business sense; what she does not conceal is a soul that unflinchingly feels and seeks human contact. We met at the British Library on the International Translation Day, where she was part of a very vibrant plenary discussing the strengths and weaknesses in publishing translations.

Ana Pérez Galván, the tranquil force behind Hispabooks, has an unwavering dream: to publish new writing from every corner of Spain in English translation, and to change readers’ perceptions of Spanish literature as eternally oscillating between the two monumental poles of Cervantes and Lorca; to revise our view of Spain as being only the realistic figment of Hemingway’s or Orwell’s imagination. Ana belongs to a very precious minority of publishers whose relationship with their trade, their art and its products is as tactile and intimate as it is philosophical, vocational and visionary. For Ana, who trained as a journalist, publishing is a gesture of love, understanding and humanity, the means to sustain a fragile and brittle national and global community. Books must make a difference, they must have narrative and cultural resonance, and the bulimic fascination with new releases, in her view, undermines our intellectual culture and publishing ethos. Her passion for words, for language, for local voices (she speaks beautifully), and the private mystery of individual lives are evinced in every novel on the Hispabooks list, and emanate powerfully in her presence. Ana’s gentle resolve conceals a sharp intelligence, a very fine instinct for meaning and for the craftsmanship of beauty, as well as a very shrewd business sense; what she does not conceal is a soul that unflinchingly feels and seeks human contact. We met at the British Library on the International Translation Day, where she was part of a very vibrant plenary discussing the strengths and weaknesses in publishing translations.

MP-C: How did you decide to become a publisher? What is your vision for Hispabooks? And did someone inspire you along the way?

APG: Ever since I began reading books on my own I was fascinated by the book as an object. It was a big wonder for me how a story could actually take the printed form and how the book itself was made. My initial curiosity was further boosted when a close cousin somewhat older than me began working as an editor. She told me about what she did and I was definitely enraptured by the magic of it all. With time, after years of working in publishing for different presses, my interest gradually shifted more and more to the core of publishing, and what ultimately makes sense out of it all, the works themselves, their nature, their content, the ideas and images conveyed in them, literature, all in all.

What types of authors or books make it on the Hispabooks list? How do you scout for them?

What types of authors or books make it on the Hispabooks list? How do you scout for them?

At Hispabooks we are set on offering the widest picture possible of what contemporary Spanish fiction looks like today within the literary fiction genre. In that sense, we try to be eclectic and select books that we believe have some added value with respect to what’s already been published in translation from Spanish into English – that can be the story or the writing itself.

What is the future of independent publishing, especially for literature in translation?

It is difficult to say, but I’d like to be optimistic about it. Independent publishing has always been a great challenge, a world of philanthropists working mostly as a labour of love. This is still very much so, but the technological tools publishers have nowadays are amazing and enable them to be ever more autonomous. Something especially true and useful when it comes down to literature in translation. Internet is a meeting point that didn’t exist years ago, and which helps to bridge frontiers and barriers that formerly were a big obstacle to building a truly global community of readers, enjoying cultural and creative exchange. Publishers nowadays have ready access to nearly everything that’s being published everywhere, in real time, and they are gradually engaging more with literature from other countries. I feel this is a very promising scenario that will contribute to a growing culture of publishing in translation.

Language is at the core of what we do. What inspires us most when engaging with a book is the writing itself; the way each writer uses it as a tool to produce an image that conveys an idea, a feeling, an approach to life.”

From contract to the printed page, how does it happen?

Once we’ve bought rights for a book, we follow very much the standard publishing process. A key point for us is choosing the best translator for each book, meaning by this the best match for each work. Each writer has his own voice, and, in a way, translators have theirs too, even if honing it as required for each work. After that, we coordinate all the editing, printing and distribution process with our editorial team and partners. We are really lucky to work with professionals of a very high standard who always engage keenly in all the work they do for us, with real care for detail. Simon Pates has designed all our covers, and it has been a real joy and an amazing experience working with him from the start. Cecilia Ross is also one of our best assets. She edits most of the translations we do, with a real gift for it.

You have some truly gifted translators working for you. What is the good of language for you? Of languages crossing paths on the pages of Hispabooks?

You have some truly gifted translators working for you. What is the good of language for you? Of languages crossing paths on the pages of Hispabooks?

Language is at the core of what we do. Being a literary fiction publisher, what inspires us most when engaging with a book is the writing itself. Not so much in terms of vocabulary but of creativeness. The way each writer uses it as a tool to produce an image that conveys an idea, a feeling, an approach to life and the human being – that is what ultimately drives our publishing plan.

Who are your ideal readers? What does it take to make us into a society of ideal readers, and would we want to be such a society?

Our ideal readers are those searching for a glimpse of the human soul, however fleeting and deceptive the picture they get might be. In this sense, they are readers looking for answers, and therefore constantly questioning themselves and the world around them, and looking forward to an open conversation on it all with others. Therefore, following this line of thought, I believe it only takes willingness and engagement with community, with ideas, with knowledge, with love, with life, all in all, to be a society of ideal readers, or rather to be plainly and simply a society, because without all that I don’t think we could rightfully call ourselves a society, just a group of people living together.

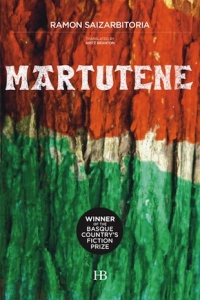

Can great literature exist in small nations? Can languages spoken by few resonate in the ears of many (the piccoli of Martutene)?

I definitely think it can. Literature, like all arts, is a means and a result of human experience, and that in itself has at the same time an individual and a universal scope. However different the cultural, ideological and idiomatic background may be between two people, at the end of the day I feel there is one common human soul where we all belong and that we all share. Sometimes this communication to and from it is straightforward, and other times it takes some extra steps, such as translation, but at the very bottom, core issues are common to all of us, whatever the culture or the language, and therefore, even if expressed in lesser-used languages, with the right bridging tools they can resonate in the ears of a large readership.

Who are the Spanish Greats? The Catalonian? The Basque? The Galician?

There are different groups of ‘greats’ to mention. In the first instance, the most renowned, like Javier Marías, Antonio Muñoz Molina, Rafael Chirbes, Almudena Grandes, Rosa Montero or Arturo Pérez Reverte. But there is a not so well-known group of Spanish writers producing really fine work too: Ignacio Martínez de Pison, Felipe Benítex Reyes, Javier Cercas, Marta Sanz, Luisgé Martín, Sara Mesa or Antonio Orejudo, for instance.

There are different groups of ‘greats’ to mention. In the first instance, the most renowned, like Javier Marías, Antonio Muñoz Molina, Rafael Chirbes, Almudena Grandes, Rosa Montero or Arturo Pérez Reverte. But there is a not so well-known group of Spanish writers producing really fine work too: Ignacio Martínez de Pison, Felipe Benítex Reyes, Javier Cercas, Marta Sanz, Luisgé Martín, Sara Mesa or Antonio Orejudo, for instance.

In Galicia, Manuel Rivas is the big writer, in Catalunya, Enrique Vila-Matas and Eduardo Mendoza, in the Basque Country Ramon Saizarbitoria and Fernando Aramburu, to name just a few.

What authors do you dream of adding to your list? Who are your favourite (non-Hispabooks) authors?

We admire the work of the great Spanish contemporary writers that have already been translated by top UK and US publishers, like Enrique Vila-Matas or Antonio Muñoz Molina, but there are also new voices from younger authors on which we’re really keen. The Boy Who Stole Attila’s Horse by Ivan Repila is a beautiful book we tried to buy but was eventually sold to Pushkin Press; The Sky Over Lima by Juan Gómez Bárcena is a great novel too that was sold to Houghton Mifflin and Oneworld, and we’d also have loved to have it in our list.

Final words of wisdom: what has publishing taught you?

Publishing has helped me achieve a sharp sense of the true value of things. It is a very deceptive world, at all levels. Starting with the book as an object itself (the power of the printed form, for instance, to endorse the content it holds is a double-edged sword), and going down through all the publishing process. A book is like an iceberg; readers only see the quarter that is visible on the surface, while the other three quarters that are underwater remain a mystery. And that mystery is all the work behind it, beginning with the creation of the work itself by the author, the months and years of writing, its translation (if there is one), the editing, and the more business-oriented part: publicity, marketing, sales and distribution. It is a fascinating journey, but usually a very demanding and tough one. The things you can do as a publisher for a book are endless, and sometimes they work and other times they don’t. It is a world where uncertainty and luck have a major part. A book’s life is as fragile as can be, and you always have to be prepared for the worse scenario possible. I’d say it’s not for the faint-hearted.

To finish: A life of books or books for life?

Books for life. I don’t understand a life without books, but I couldn’t think either about a life without many other things. Books give us the opportunity to reflect on things we wouldn’t reflect on otherwise and to do so in a very unique way, but ultimately, like it or not, it is in those things where life happens. It is then our attempt to reflect on and understand them that inspires new books, and it all starts over and over again.

Ana Pérez Galván is the managing director of Hispabooks, which she founded with editorial director Gregorio Doval in October 2011, with a remit to bring contemporary Spanish writers in English translation to a global audience. She is based in Madrid..

hispabooks.com

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.