At last

by khulud khamis

“An explosive and powerful new collection… a fantastic, liberating book… incredibly empowering and life-affirming.” Ayesha Hazarika

It is another Friday evening, and I climb the four stories of Noor’s building with its small, rectangular windows that let in only thin slivers of brownish yellow light. The lightbulbs on the third and fourth landings are burned out, so I make my way in almost complete darkness by counting the stairs.

At first, there was something exhilarating about the secrecy.

A part of my life that belonged only to me. A small slice of myself I didn’t have to share with Tareq, my mother, my sister, my friends.

Now the novelty of it has faded, and the secret – well, it’s not quite a secret anymore.

A few of Noor’s friends know. On the rare occasions we venture out of her apartment to a café, or even just a walk on the beach together, I’m constantly on edge, jumpy whenever Noor touches me, afraid someone I know will see the intimacy in our gestures.

I carry this secret with me everywhere; a kettlebell, pulling me down.

By the time I reach the fourth floor, my breath comes in shallow gulps, my heartbeat a small hammer in my neck, and heat has spread in my stomach. I knock on the door and wait a few seconds before unlocking it with the key Noor had given me only a few weeks after we started seeing each other.

That was almost four years ago.

‘You know you don’t have to knock before you unlock the door. That’s the whole point of having your own key,’ Noor is sitting at her easel next to the window, wearing just a tank top and her paint-splattered jean shorts, the harsh white light accentuating the cellulite on her thighs, the tiny varicose veins running down the insides of her calves. Her hair, with its few silver strands, is in a messy bun held by a brush at the top of her head. When she turns around and reaches for a hug, I see the painting she’s working on. Two female figures, again.

‘Whiskey?’ Noor holds her half-empty glass to me. I kick off my high heels, take a long sip of the whiskey, and kiss her bare shoulder. ‘Hmm, smooth.’ She grins at me. ‘The whiskey, not your shoulder.’

The painting is of the same two female figures she has been painting, obsessively, for some time now – each time with variations of composition, background, and the positioning of the figures. But this time, something is slightly off. I can identify one of the figures as Noor, not from her features, as the figures are more abstract than realistic, but rather from the carefree, open way she carries herself. But what stops me is the second figure, the one I imagine is me. Or is she? We never discussed the identity of these women. She is usually a bit further in, a little blurred, or blending into the background, and always wearing high heels. Something in the mood around her in this painting is a bit off-character, and then there is the way her right foot is in mid-air: fast strokes of the paintbrush, to give the effect of movement. She’s wearing only one sandal, on the foot that is grounded.

And then I see it. Or the absence of it. There are no high heels in the painting. The sandal on her left foot is flat.

I am too embarrassed to ask about this change, so I remain silent.

I wait for the inevitable subject to come up – asking if I have told my family yet about us – but she doesn’t say anything. The last time we had this same argument, we were both a bit drunk. Later, she apologised for accusing me of being ashamed of who I was, of living in the shadows, a hypocrisy. I don’t know if her silence since then means defeat, that she has accepted this as a fact, or if she’s being passive-aggressive.

The painting is of the same two female figures she has been painting, obsessively, for some time now – each time with variations. But this time, something is slightly off.”

Two glasses of whiskey later we are in the bedroom, laying naked on the narrow bed, facing each other. Noor runs her fingers up and down my thigh, stopping just for a moment at my cellulite marks. I stroke her small, bare breasts, gently circling her nipples.

Our lovemaking is a slow dance; we take turns leading, gently, our bodies moving in synchronicity. It is as if part of me has crawled inside her and knows exactly what she is feeling at every given moment.

Words become obsolete.

Her touch is a soothing familiarity but at the same time there is always something new, a small surprise, and my body trembles with expectation of the unknown.

I have no need for light, though Noor desires it. Tonight, our bodies are illuminated a dark yellow from several lit candles, scattered on the floor around the room.

Noor takes my body to places I have never known. I had my first orgasm with her, at the age of forty-four. I didn’t know such sublime pleasure existed in the world.

Our song is on repeat. Etta James’ ‘At Last’.

Her hand now travels up my breasts, first the left one, then the right. She squeezes my nipple, at first gently, then gradually harder. I moan into her mouth. The slight, exquisite pain sends a shock of electricity down my body. Noor pulls away. ‘Oh, you like it and you want more,’ and she squeezes my nipple harder and at the same time pulls on it, all the while watching me. I struggle to remain composed. ‘Let go,’ she whispers into my ear. ‘Let go, Nadia habibti. Yes, like that. Take pleasure in your body.’

I close my eyes and let go, giving up my body to her.

While she keeps pulling at my nipple, her other hand journeys down my stomach, encircles my bellybutton, then starts circling my clitoris, slowly. My orgasm is lava that builds up on the inside, bubbling, boiling, until it bursts out in short, violent waves. I count four before collapsing. Before Noor, I didn’t know my body was capable of such intensities.

I lay on my back, spent. Noor doesn’t expect me to pleasure her just now, which I still find surprising. She takes the vibrator out of the nightstand drawer, turns it on, and presses it down hard on her clitoris, making fast, tiny circular movements. I watch her with fascination. When she begins moaning, I come and suckle at her breast, my fingers at her other nipple, kneading, pulling. Her orgasm comes in abrupt, short staccato trembles of her whole body.

I keep my eyes open, waiting for Noor to fall back asleep so I can silently slip out of bed and go home, out of sheer habit. Then I remember that Tareq is away for the weekend. For the first time in our relationship, I stay.”

It is well after midnight when I wake up, disoriented. Then I remember that I never went home.

Home. But where is my home?

I have finally found genuine joy in my life, and yet I have managed to confine it to a few hours once a week on Friday nights.

I cuddle up to Noor from behind, my face close to her neck, and breathe in the familiar sweet-sour scent of her sweat. I run my hand lightly over her naked back, from her lovely slender neck all the way to her tailbone and back up. Her back slightly arches in response to my touch. She turns around to face me. ‘You’re still here,’ she smiles, her voice hoarse from sleep, her breath whiskey. ‘Hey,’ I whisper, kissing her on the nose. I touch the tiny vertical wrinkles that have been quietly forming above her mouth. She heaves one naked leg over me, trapping my body underneath. I know I should get back home; I keep my eyes open, waiting for Noor to fall back asleep so I can silently slip out of bed and go home, out of sheer habit. Then I remember that Tareq is away for the weekend. For the first time in our relationship, I stay with Noor until late morning.

—

Monday morning, and I am sitting at my office desk, staring at the organisational budget Excel sheet. Amjad the accountant has been snappy with me all week, impatient about getting him the quarterly financial report. I’m already one week late. I’ve been staring at the numbers for the last two hours, unable to make sense of them. My mind keeps wandering back to Saturday morning, that feeling of comfort – of home – waking up next to Noor. I want to be that woman with her foot mid-air, stepping out of the shadows and into truth.

The realisation is so sudden I gasp aloud. Suddenly, everything is crystal clear in my head. I know I want to wake up next to this lovely, beautiful woman every day. I want to be that free woman in her paintings.

I am forty-eight years old, and still afraid to live my life without fear of what will people say. It’s ridiculous. Tareq is finally moving out of the house next month. My sister will understand; she’s been suspecting it for a while anyway, dropping hints at every occasion. When I take a minute to truly think about it, I realise I don’t really care whether my friends will accept it. It is not their life I am living. It has no bearing on them. And my mother, well, she won’t have a choice but to accept it. I am forty-eight years old. It’s about time I start living my own truth. Not this hypocrisy, this pretend life.

I am giddy with this new and sudden joy, imagining Noor’s elation at the news.

At last.

Unable to wait until Friday night to tell her, I grab my bag and rush out of the office. On my way, I send a quick message to Amjad: sorry, family emergency. Your report will have to wait until tomorrow.

I climb the four floors as fast as I can in these damn heels, precariously balancing my weight on the balls of my feet, the heels suspended in air at the end of each step. My feet are aching from the walk, but oh, the small, painful sacrifices we make for appearances. At the door, I stop for a few moments to recover. As I wait for my heartbeat and breathing to slow down, I hear laughter from inside. Then voices. Just before turning the key in, I hear an unfamiliar female voice, ‘so when will you tell Nadia?’ I freeze at the mention of my name. I stare at the ugly dark brown of the door, which I am noticing for the first time. But then I’ve only ever been here at night. ‘Why should I tell her? I don’t owe her anything. She isn’t fully committed, so I don’t have to be either.’ What is she talking about? I can’t make out what they say next, as their voices are now lower. Then, Noor’s voice again: ‘I do love her, but I can’t do this once-a-week thing anymore. I need a real relationship. She promised me she’d tell her son and mother months ago, but so far, nothing. She thinks she can live this double life forever. But I can’t do this. I can’t do secrets like she does.’

Then, the voice of Etta James comes on.

Our song, ‘At Last’.

I pull the key slowly out of the keyhole, my fingers clammy from the humidity. My heartbeat again a small hammer in my neck. I take off my high heels, leaning on the wall, and walk down the four stories of the building barefoot, my legs trembling with each step.

Outside, I stand in the scorching sun, beads of sweat a tiny pool between my breasts. A few couples are sitting at the outside tables of the café on the street corner, going on about their daily lives. I take my phone out of my bag and send a message to Amjad: ‘You’ll have your report by the end of the day.’

I put my high heels on for the last time and head back to the office.

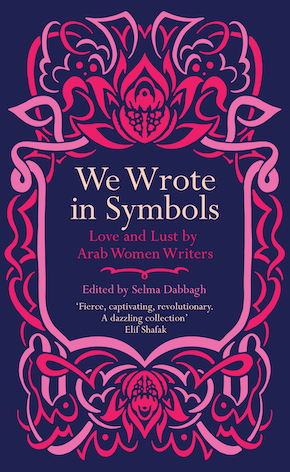

From We Wrote in Symbols: Love and Lust by Arab Women Writers, edited by Selma Dabbagh (Saqi Books)

khulud khamis is a Slovak-Palestinian feminist writer. The Italian translation of her novel Haifa Fragments (Spinifex Press, 2015) was awarded second place in the 2018 Premio Letterario Citta di Siena literary award. Her short stories have appeared in Verity La, FemAsia Magazine and Consequence Magazine. We Wrote in Symbols is published by Saqi Books in paperback and eBook.

khulud khamis is a Slovak-Palestinian feminist writer. The Italian translation of her novel Haifa Fragments (Spinifex Press, 2015) was awarded second place in the 2018 Premio Letterario Citta di Siena literary award. Her short stories have appeared in Verity La, FemAsia Magazine and Consequence Magazine. We Wrote in Symbols is published by Saqi Books in paperback and eBook.

Read more

khuludkhamis.com

khulud.khamis

@khulud_khamis

@SaqiBooks

Selma Dabbagh is a British Palestinian writer of fiction whose debut novel Out of It (Bloomsbury) was a Guardian Book of the Year. Her BBC Radio 4 play The Brick was nominated for the Imison Award, and her writing has been published in Granta and Wasafiri, and translated into several languages.

selmadabbagh.com

selmadabbagh

@SelmaDabbagh