Boris Fishman: Believable lies

by Mark ReynoldsBoris Fishman’s engaging debut novel A Replacement Life offers a critical and affectionate portrait of the Russian-American immigrant community that clusters around South Brooklyn’s Brighton Beach. Slava Gelman is a lowly hack on a New Yorker-style magazine whose grandfather suggests an outrageous writing assignment: to forge a Holocaust restitution claim. His grandmother, an actual Holocaust survivor, narrowly missed out on a payout from the authorities when she died just as the qualification rules were changed – and grandfather wants compensation, crooked or not. As Slava is pulled back from Manhattan into the community that shaped him, this immediate dilemma sets up an entertaining and provocative exploration of moral choice, identity and the art of storytelling.

MR: The book gives a snapshot of a community connected by language, but with widely differing backgrounds. Is ‘Russian-American’, an inappropriate shorthand for the waves of immigrants who have populated South Brooklyn?

BF: “I guess the most technically accurate description would be ‘Russian-speaking ex-Soviets’, or ‘Russian-speaking Soviet Americans’. Let me get into every piece of that. They’re not Russian-Americans because, as you say, they come from different parts of the former Soviet Union, but also because so many of them who came in the 70s and 80s are far more defined by the Soviet experience than anything that came afterward. People such as my family came officially for religious reasons, but it was more for political reasons. But the one thing that unites all these people, thanks to the dubious blessing of the empire they were part of, is the language they speak. All of them can speak Russian, even if they don’t speak it primarily. So a funny thing happens: in the Soviet Union, we were primarily Jews, and as much as we wanted to forget that, we were constantly reminded of it by the people around us. We were invested in blending in; they were invested in keeping us out.

“Once you get to America, those divisions fall away, and instead of being Jewish you become Russian – both to the Americans who are now the ones evaluating you from the ringside seats, and also to your fellow ex-Soviets, who are now far more invested in clinging socially and psychologically to someone who resembles them in this foreign place; far more interested in that than in beating up on a minority, which was a motivation back home. There’s a really toxic strain back in that part of the world that finds strength through xenophobia, through the demonisation of minorities or foreigners. Half of Russian national identity today, I feel, is based on anti-Americanism; just doing the opposite of what the Americans do. I find Russia’s obsession with America fascinating. They try so hard! It’s like the kid who pretends he doesn’t like the girl and hits her a lot to show everyone he doesn’t like her, but in fact he’s obsessed with her. It’s juvenile.”

I’m deeply connected to Russian food, Russian humour, literature, history, and notions of interpersonal interaction, but the way life is lived in South Brooklyn, the psychological space there, I want no part of.”

What was it that attracted these immigrants to South Brooklyn in particular, and what keeps them there?

“Well, in the first place it’s much cheaper than the rest of the city. Secondly, it’s right by the ocean, and many of the original waves came from Odessa in Ukraine, a heavily Jewish city right on the Black Sea. So Brighton Beach, which is the iconic Russian-speaking neighbourhood in South Brooklyn, is called Little Odessa. And it is really magnificent, the beach is just incredibly wide and soft and golden. In terms of what keeps them there, they keep themselves there. The children of those who came in the 70s have fanned out to neighbouring areas that are more prosperous economically and have slightly fancier amenities, a different kind of restaurant perhaps, but psychologically they remain the same kinds of places.

“Of course many have moved out to Manhattan, or to more northern parts of Brooklyn, but it never ceases to fascinate me how lightly worn these people’s Americanism is. I mean, they’re conversant in American culture, in American pop culture, and yet one foot stays firmly in the everydayness of South Brooklyn. They speak to their parents seven times a day, they consume the same products, and draw their sense of self from those environments. Whereas for me, I’m deeply connected to Russian food, Russian humour, literature, history, and notions of interpersonal interaction, but the way life is lived in South Brooklyn, the psychological space there, I want no part of. Because every day the familiar gets chosen over the adventuresome in that part of the city, and that’s not the way I want to live.”

What is it that Slava was desperate to leave behind by moving to Manhattan, and was he ever going to achieve it?

“Slava wants to get away for reasons good and bad. When I was a teenager I sensed that some of the things my parents wanted for me were not ideal ways to actualise my potential as a human being. Even as young people we have a sense of what’s right for us. We often can’t intellectualise it, but the radar is there in an embryonic way and it does give you a feeling in your gut that suggests the right direction. So the less sophisticated reason that Slava wants to leave is that he’s embarrassed; these people are hustlers and they look at ways to get around the law, and instead of reading books they’re watching television, and they eat too much, and all kinds of things like that. He’s embarrassed at being like people who are nothing like the majority of the people in the country he’s moved into. On the other hand, he also has another, more admirable reason for wanting to leave, which is that he believes he has a debt to the country that has taken in his family, to understand it on its own terms.

“There’s something incredibly ungenerous about the way his people live, which is to say the country they moved into is generous enough to leave them alone, and they’re eager to take advantage of that. They never venture into non-Russian-speaking parts of the city unless they have to. There is a kind of slogan in Brighton Beach: ‘We don’t go to America’. But Slava wants to make himself uncomfortable by confronting the new and the unfamiliar that his community’s life is built around avoiding. And that’s Soviet life to the core. Whenever something’s new and unfamiliar, that means it’s bad.”

And to what extent have you yourself broken free of that community, and in what ways does it pull you back?

“I never broke free in the way Slava tries to, but I sensed some of the same things. It requires a kind of arrogant heartlessness to say this way of life, between me and my community, will end and something new will begin. I did not have it in me to commit that cruelty. So I spent the last fifteen years inching my way out instead of sprinting, and I think there’s something kinder and nobler in doing it gradually so you don’t break the hearts of the people whom you love but from whom you happen to be different.

“But the general pattern moves in ten-year increments. I came to America from Belarus at 9, I tried for ten years to suppress every indicator of my background – down to telling friends my name was Bobby, which felt like the perfect American name: blond hair, football player, the dream.

“And then at about 18, we read Fathers and Sons by Turgenev in high school, and it just unleashed something that had been dammed up. Interestingly we had read Crime and Punishment by then, and that had done nothing, but Fathers and Sons set something free, that kind of heartfelt romantic treatment of the questions that torment Russians who are so deeply invested in resolving their country’s fate. And I finally looked behind me to see what I’d left there, and that led to majoring in Russian literature in college, and going to Moscow to work at the US Embassy for a summer, and of course all these experiences, these attempts at recovery, showed me that actually I didn’t want to recover everything, I only wanted to recover some things. And so the next ten years were spent picking up these various pieces and saying, do I want this? Hmm, No. Do I want this? Yeah, I do.

“And so now, twenty or twenty-five years later, I feel like I’m finally in a place where I know what I want and what I don’t want, the parts of the community that I’m happy to embrace and the parts where I feel comfortable saying thank you but no thank you. And the same goes for the country itself. There are parts of modern Russia that I admire, and parts of it that I disown completely, and my gift to myself, the function of a grown-up’s confidence, is to say: I don’t need your permission to tell me whether it’s OK to take this but leave that; I have that authority for myself. That’s also the kind of path that Slava begins on in the course of the novel, discovering the confidence to decide for himself what pieces of the identities available to him he wants to take for himself. His girlfriend Arianna introduces him to the notion he doesn’t have to wait for someone to tell him who he is, and he also doesn’t have to be this or that. He can be pieces of different things that are renegotiated at every moment of every day, and he gets to be the judge of which is which.”

OK, so what happened to Bobby?

“Ha, ha. It won’t surprise you, and actually it’s perfectly symbolic, that I was outed by my parents. We spent five years in South Brooklyn, then to my father’s everlasting credit, he said, ‘I didn’t come to America to live among Russians,’ and he moved us out to northern New Jersey, to a kind of spiritless suburbia. I seized my opportunity: I had a new set of friends on the town’s recreational tennis team, who I told my name was Bobby. My parents came to pick me up one day earlier than they were supposed to and they started calling out my name. And not only were they calling out my real name, they were calling it out in its Russian inflection: in English it’s Boris, in Russian it’s BoREES, which is about as barbaric a sound to me at that age as I could imagine, I mean truly like the Visigoths were storming through the gates, and I was actually hiding, hoping they would stop and get back in the car. The tennis courts have this astroturf that surrounds it and it dampens the strike of the ball when it hits the fence, and I was hiding behind this and a friend came up to me and said, ‘Er, Bobby? I think your parents are looking for you.’ And far more interesting than what was going on in my head at that moment is what was going on in his head, because he also was thirteen and was having to process this kid who’s told us his name is Bobby but probably it’s Boris, so what’s going on there? It’s an interesting thing to imagine.”

My parents were calling out my real name, in its Russian inflection: BoREES, which is about as barbaric a sound to me at that age as I could imagine, like the Visigoths were storming through the gates.”

So just how much of the book is biographical – and autobiographical?

“I wrote a whole essay on this subject for a literary blog back in the States. I found that autobiography actually hinders because in order to make real life work as drama you have to alter it, falsify it, punch this up, shorten this, work this, distil that. The requirements of drama are completely different from the requirements of real life. If you transcribe your life, it’s just leaden inconsequence most of the time. So when you’re inventing from whole cloth, I feel it’s a lot easier to be cold and impersonal and objective, to know what falls out and what stays in. When you’re drawing from real life, the blinders are on in a big way, and it makes it much harder to discern what should stay and what should go. Also, if a Russian person is reading your book they need one kind of explanation (or lack thereof), but a non-Russian needs slightly more hand-holding. But you’re only writing one book for everyone, so how do you decide what to explain and when? You have to make that decision over and over, ten times a page.

“So, to actually answer your question, my own grandmother was a Holocaust survivor and, unlike Slava, whose experiences in the novel are fuelled by the fact that he fails to get her stories before she dies, I did get my grandmother’s stories before she went, and they serve as a kind of broad inspiration for the things that are described in the novel. But the ironic thing is that they also have to be falsified – which I enjoyed, because I’m doing for the purposes of the novel the same thing Slava’s doing for the purposes of the false claims. I didn’t even think twice about falsifying my grandmother’s real story in order to make it work dramatically. The problem is after a while you forget what you invented and what’s real, and I’ll often be speaking about something and will not be able to recall whether that was a piece of my grandmother’s real life or whether I invented it for the novel.

“Some sentences begin as non-fiction and end as fiction. My grandfather did not ask me to forge holocaust restitution claims, but temperamentally that is him; the words the character utters in the novel are invented but, again, those are things my grandfather may very well say. The grandfather is based on mine. His friend Israel is invented from whole cloth. Arianna is based on someone who was in my life, but Vera – the girl Slava’s family would pick because she’s the familiar, comfortable choice – was wholly invented.

“Very often a scene, like where grandfather haggles over the price of a plot in the graveyard, or when the Gelman family goes to Lenin’s tomb in Moscow, the kernels of those scenes are from real life, but literally just the one-line mention in the New York Post about someone selling graves on the side. And then all the leaves on that tree I will have invented. Slava has this thing where he can’t get going on a story unless grandfather gives him the kernel of a factual occurrence from grandmother’s actual life. It was very similar with me, I needed some kind of non-fiction to get me going, but I prefer to then forget it entirely and build something from scratch.”

How often have you been back to Belarus?

“Just once, which was more than enough. This was the summer I spent in Moscow, and I took a side trip to Minsk, the quintessential revisiting of one’s childhood play spaces. You know the enormous, thousand-apartment buildings that are all over that part of the world? So we had an equally enormous yard that spanned five entryways and a thousand apartments, and to me seemed like the size of the universe itself when I was six years old, and of course on encountering it as an adult I was struck by how small it actually was. But that was our universe, me and my friends. We had lots of chestnut trees and so that was our currency. We didn’t have any actual money, but we paid each other and traded in chestnuts, and the experience of popping open that spiky green shell sends off really sharp emotions inside me.”

We don’t hear much news out of Belarus, but under Lukashenko’s dictatorship, it really does seem to be a place that, as you say about South Brooklyn, is ‘stuck forever in Soviet times’.

“But we also have to understand that, except for a minority of freedom activists and people who ideologically disagree with what this man has done, it is my sense that the vast majority of the population is quite content. It is not a wealthy life, but it is a secure life, a stable life, pensions come on time, and increase incrementally, it’s safe, it’s predictable. Part of the reason he remains in power is that he’s ruthless, but also a surprising proportion of the population is OK with the way things are. Russia’s course over the last fifteen years is defined by the shock and terror people experienced under Yeltsin in the 90s. It was pure chaos and lawlessness, and nothing is more terrifying than that. I think Belarus is kind of a strange place in that sense, the citizens are invested in the stability the regime brings.”

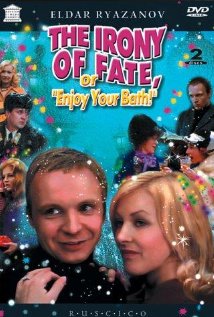

Your character Israel references a Soviet film about a man who wakes up in the wrong apartment after a New Year’s party. Which of course I googled, and found The Irony of Fate (1975). Is this a film you fondly recall from growing up in Minsk, or is such a detail the result of research?

Your character Israel references a Soviet film about a man who wakes up in the wrong apartment after a New Year’s party. Which of course I googled, and found The Irony of Fate (1975). Is this a film you fondly recall from growing up in Minsk, or is such a detail the result of research?

“That is an iconic Soviet film. You know how there’s a tradition in America of watching It’s a Wonderful Life at Christmas? Over there you watch that movie on New Year’s Eve, it’s incredibly sweet. But there’s also a moment in the book where somebody quotes from another Soviet movie, and that’s invented. Or somebody quotes a Soviet slogan: ‘Get yourself noticed, get yourself problems.’ That’s made up. And how wonderful and liberating it is to invent something like that, that smells like fact. I enjoy leading the reader into that suggestion, and then, should the question ever come up, admitting it actually was completely invented. But even rabid anti-Soviet people have a soft spot for the cultural production of their time and place. For example cartoons, you won’t meet an ex-Soviet person without an incredible soft spot for Soviet cartoons. If you care to google one more, just for your own viewing pleasure, it’s called Hedgehog in the Fog and it is utterly enchanting.”

The New York Times review of the book identifies an exploration of ‘truth and fact, conscience and law, head and groin’. Does that neatly sum up the themes you were setting out to tackle?

“Very much so. But probably the one that applies the least is ‘head and groin’. It was really important for me to put sex into the novel, because I feel like there’s a kind of abdication in contemporary American literature of the kind of relations that take place between the sexes in our twenties. There’s a wonderful essay by a woman named Katie Roiphe, called ‘The Naked and the Conflicted’. Her argument basically is that people like John Updike and Norman Mailer and Philip Roth overdid it in one direction, they objectified their female characters and turned them into sexual objects, whereas today’s young male American novelists, they’ll have a conversation, they’ll have some light petting, but the classic sexual impulse has disappeared, and I think that’s a real shame. It’s an indication of the very confused role that men in America have today, and it’s a subject that interests me a great deal and something I want to write about. But there’s actually not a great deal of conflict between head and groin.

“The other two, absolutely. Conscience and law… do you know what love is in a Soviet family? It’s agreeing on everything: You show me you love me by agreeing with me. There’s no tolerance for divergence. What we’re talking about there is the difference between a totalitarian system and a democratic system that withstands dissent; it also functions on the family level. So you have this mission of wanting to honour your elders for their sacrifice, and yet the only honour they’ll accept is one that’s untenable to you. How do you resolve that question? I found that a really rich query.

“The other theme of course is about the restitution claims which, as you may know, have evolved over time. When they were formulated initially, you had to have been an inmate of the ghetto for a particular period of time. But then 18 months became 6 months, and 6 months became 3 months, so what was illegal yesterday is legal today. But what about all the people who died in the interim? They weren’t eligible to apply. What about all the people who were killed, six million of them? It doesn’t have to be limited to a Jewish tragedy; eleven million, what about them? And if you are someone who has been screwed by one authority after another for the duration of your life, when someone says to them, ‘Ah, but you didn’t suffer in the exact way you needed to have suffered in order to qualify,’ it’s not an argument that goes a very long way.

“The extract on Bookanista tries to get into that, and the thing I hope readers take away is I want them to be confused about who’s right – or to believe that both of them have a point. Then later on you have Otto – the German’s voice is actually the voice of morality and reason in the novel. Where Slava says just pay them all, it still will never be enough, Otto says it’s precisely because there can never be justice that the law is all that we have. It may be appropriate on an individual level now and then to take justice into your hands – if you were an African-American in the United States 150 years ago, the state was not looking out for your best interests and you were very justified in taking the law into your own hands in a kind of moral, cosmic sense. But if all of us do that at the same time, what then? I wanted to pose these impossible questions. Because what is the purpose of fiction if not to do that? I’m really devoted to the tradition in Russian literature from the nineteenth century that wanted to ask the biggest questions about who we are and which way we are heading as people, as countries and so on. I often read novels that are very impressive on some kind of technical level, but what they go for is so little. I’d rather fail at something big than succeed in something little. I’ve no interest in capturing small moments.”

If you need to lie, you need superfluous detail. A lie constructed in a laboratory will mention only the essential things, but the superfluous indicates real living.”

A memorable phrase in the novel about the nature of storytelling is one you borrowed from Gabriel García Márquez “If you say there are elephants flying outside your window, no one will believe you. But if you say there are six elephants flying outside your window, it’s a different story.” Although García Márquez actually said 425 elephants. Why the shift?

“Obviously if you stop to think about it there are no elephants, elephants can’t fly outside your window, but there’s something so plausible about the number six that there isn’t about the number 425 that for a nanosecond you’ll think twice. If you need to lie, concrete detail is one thing that’s essential, but you also need superfluous detail. A lie constructed in a laboratory will mention only the essential things, but the superfluous indicates real living. There’s a moment in the novel where Slava realises, Holy shit, I have become a great liar! It’s a really ambivalent power and skill to be able to lie to people, and he realises that he needs to restrain himself.”

… because it’s wrecking his relationship with Arianna.

“That’s right, you achieve one end superlatively but then you pay a price. That is one of the animating principles of the novel psychologically, that there is always a price attached.”

At what point did you discover that your invention of a series of fake Holocaust restitution claims had actually happened? And were you annoyed or vindicated by this discovery?

“I started writing in the fall of 2009, and I finished my first draft in September 2010. Then in November 2010 when that article appeared in the New York Times, I wrote an essay for Tablet where I tried to provide context for why these people had done what they’d done. Legally, I said, there’s no question: they’re culpable. Prosecute them, send them to prison. But morally, it’s a complicated story. These are people who’ve suffered their whole lives and spent 50, 60, 70 years in a system where very often the only way to achieve justice was to bribe someone. Corruption was often the only way to justice, by any reasonable human marker, so let’s not dismiss them as aberrations or pure evil. And I was eviscerated in the comments section as a defender of criminals.

“I think maybe because the novel is longer and more nuanced, I have not had any response of that kind since it came out. But I didn’t think my thunder had been stolen, I felt a kind of vindication. It is the problem of all insular communities that the laundry stays unaired, and this is a great problem in the orthodox Jewish community in New York City. This whole novel is just about holding up the mirror to my community and saying, hey, you need to look at this, you need to think about this. Though it’s interesting, I used to be a journalist and most of my work centred on the Russian experience – there, here, hyphenated, non-hyphenated – and I was a mainstay on Russian radio and Russian newspapers down in South Brooklyn. Since this novel came out, absolutely no communication whatsoever.”

Art doesn’t move forward unless you push the boundaries, but there’s an enormous contingent of the American population and the American political leadership that sees that as frivolity and self-indulgence.”

You were on the NYU MFA program and also acknowledge various residencies and organisations that have supported your writing. So which individuals and institutions have offered the greatest help?

“Well, I found the world of journalism rather stingy in the mentorship department. The heart shows up more, broadly speaking, in the world of publishing, and I found more people willing to be generous in that world than I did in journalism. There’s a kind of utilitarianism that holds the day in journalism that isn’t the case in fiction. So someone like Joyce Carol Oates, who taught me at Princeton and remembered me ten years later, wanted to support the novel. Margaret Atwood, whom I fact-checked once at the New York Times Magazine, I mentioned that I had got a novel coming, and she said, when it does, let me know and I’ll tweet about it. I mean, what does Margaret Atwood have to do this for except to be a mensch, as they say, a good person?

“In terms of institutions, every single one of the residencies I’ve attended, even when they are quite obviously tax write-offs for wealthy people, there’s a special place in heaven for these people because the American Government just does not support the arts in the way the Canadian or the French does. Art doesn’t move forward unless you push the boundaries, but there’s an enormous contingent of the American population and the American political leadership that sees that as frivolity and self-indulgence, as a kind of elitism and intellectualism. We’ve spoken a lot about what I do and don’t want from my Russian heritage, there are also things I do and don’t want for my adopted American self, and one of them is this anti-intellectual strain in American life.

“So I have a lot of time for the institutions that give writers time and space to work, while asking for almost nothing in return. And then of course there’s the common criticism of the MFA system, that it turns out technically proficient but soulless writers. But the MFA programme doesn’t turn people with soul into soulless writers. If you don’t have much soul, sure, an MFA can’t give that to you, it can only teach you technical proficiency. But if you happen to have a little bit of soul, it can make you magnificent. Because no matter how much soul you have, if you don’t have certain technical knowhow you will be unbearable to read. You need the technical chops to bring it to the surface in a way that hooks the reader. The MFA gave me structure, it gave me discipline, it gave me a community of thirteen people who were in the same boat as I was. I started writing every day, which I think is essential for a writer, only when I enrolled in that programme. So I’m a great defender of MFAs, as long as you don’t expect them to make you an interesting person. You’ve got to do that on your own.”

ONE will be also publishing your next novel, Don’t Let My Baby Do Rodeo. Is it finished? When can we expect to see it? And can you say something about the plot?

“It is finished. It’s coming out in early 2016 in the US, so it will be out here soon afterward. I really did not want to lean on my experiences again. I wanted to write out of a different kind of life and mind, so it’s written from a woman’s perspective, an older woman, an adoptive mother who 25 years before came to America as one of the first exchange students after Gorbachev came to power. It’s about this Russian-American family in New Jersey that adopts a boy from Montana who turns out to be, in their eyes, feral, which is a very literal, stylised rendering of the way that many people on the East Coast of the States see the mountain West. They end up heading out West in order to try and find the birth parents and figure out what’s wrong with him. Because, like typical Russians, they’re convinced they were conned and the birth records failed to mention something they needed to know.

“There are two epigraphs to the novel, and one is from James Baldwin, which says man will and must build all sorts of physical entities, but ‘he is also enjoined to understand the great wilderness of himself’. And so there’s a parallel between the literal wilderness and the wilderness of the heart. So, as usual, it’s basically about different kinds of foreignness and belonging.”

And what other projects are you working on?

“Quite a few. I’m thinking of doing a Ukrainian cookbook. The woman who looks after my grandfather is an incredible cook, and I followed her to Ukraine last year with a photographer and captured her life a bit. I had to put it on the back burner because I underestimated how challenging it would be to do a cookbook – you kind of have to be a scientist in order to do it well.

“Also I’m very interested in doing a book about masculinity. There’s an American writer called Jim Harrison who lives in Montana, close to nature, who would be my conduit into the story. I sought him out at a certain time in my life when I was trying to figure out who I was, and was displeased with the examples of malehood that I was seeing from my grandfather who was too alpha, and my father who’s not alpha enough. I wanted to believe that some other way of being a guy was possible, but I simply didn’t know how. And Jim’s work gave me that third way. He has male characters who are at once strong and resolute in classic ways, but also unembarrassed by sophistication and emotion and familiarity with the arts and things like that. So Finding Mr Harrison is a kind of memoir project. I come out of non-fiction, and I’m desperate to get back to it.

“However, when a novel idea blooms in your head it’s very hard to set it aside, and I’m really interested in writing an nineteenth-century-style Russian family novel, but set in the future, a generation ahead. I’m part of a generation, getting back to the masculinity questions, where suddenly women are tanks and men are doormats, which is an overcorrection to the problem that we had before. And I’m imagining my generation’s children wishing to restore a kind of classic rebalancing of gender roles. Obviously this is unformed, it requires some dramatic situation that I haven’t come up with yet, but I’m basically writing an old-fashioned family novel set in the future. I’m imagining passing into a world where Facebook and Twitter are really now déclassé, sort of like smoking, nobody does it anymore. America’s role in the world is slightly reduced, the empire hasn’t collapsed but it’s no longer the superpower it once was.

“It’s something I have absolutely no idea how to do, much as I didn’t with the female voice in the second novel, so that is the signal that it’s the right thing to try. If I wrote another novel with a mid-30s Jewish-Russian male hero, take me out to the shed, because that is not the way to do things.”

Boris Fishman was born in Minsk in the former Soviet Union in 1979, and emigrated to the United States in 1988. His journalism, essays, and criticism have appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times Magazine and Book Review, the New Republic, the Nation, Harper’s, Vogue, the London Review of Books, The Wall Street Journal and other publications. A Replacement Life is published by ONE. Read more.

Boris Fishman was born in Minsk in the former Soviet Union in 1979, and emigrated to the United States in 1988. His journalism, essays, and criticism have appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times Magazine and Book Review, the New Republic, the Nation, Harper’s, Vogue, the London Review of Books, The Wall Street Journal and other publications. A Replacement Life is published by ONE. Read more.

borisfishman.com

Author portrait © Rob Liguori

Read an extract from A Replacement Life

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.