Celebrating the Year of the Witch

by Camilla Bruce

Some young girls are into sports, some are into fashion, and some spend their teenage years building altars in their bedrooms, summoning spirits and casting spells. At least up until recently, there were perhaps not that many of us – and we did run the risk of being branded as weird, but some of my fondest memories from that time is of stuffing cinnamon, rosemary and other household spices into hand-stitched flannel bags, carving runes into my mother’s candles, and memorising Latin words that I definitely didn’t know the meaning of. All this to say that, although the interest in witches is flourishing right now – and 2023 has been dubbed the ‘the year of the witch’ due to the sheer number of books and other media coming out – there have always been those among us who are drawn to the idea of magic and witchcraft, and it wouldn’t surprise at all if some of the other authors embarking on witchy tales this year also were ‘weird girls’ growing up.

People with far more impressive academic credentials than me have looked into the relationship between teenage girls and witchcraft, so I won’t attempt an in-depth examination, other than to point out that magic – within or outside of a religious context – has always been a tool for the oppressed: something to cling to when one feels powerless. Whether the spells and incantations work is perhaps not all that important – perhaps the only thing that matters is the sense of power and control they invoke when the world feels hopeless or chaotic. In that sense, there’s more to witchcraft than attitude and cool, black clothes, and the practice has perhaps more in common with trendy crystal healing and visualisation techniques than either camp likes to think about.

There are many different kinds of witches, though, and that shows in literature as well. The most important distinction in my head is between the historical witch, and what I think of as the mythical one. The historical category is a crowded space, but I’m mostly thinking of the victims of the witch trials; the thousands of innocent people who were tortured, hanged or burned for crimes they did not commit. Several of the accused had worked as midwives or healers, and had probably done a lot of good in a world with limited healthcare before they were put on trial. At the very least they were normal people with normal lives, who had most certainly not sent wicked spirits out at night to steal milk from their neighbour’s cows.

Although the fairy-tale witch with her crooked nose has often been deemed a negative female stereotype, I’m not entirely willing to dismiss her. In fact, I find her inspirational.”

The mythical witch is somewhat inspired by the historical witch. In this narrative, the witch hunters’ beliefs and the accused’s own testimonies – given under duress, and influenced by folklore – blend together to create a powerful figure who can indeed help or harm through supernatural means. The mythical witch is the witch that the witch hunters thought they were hunting, instead of the farm wives they actually caught. And she is very mighty, too – few other characters have inspired more legends, books or movies than the witch; standing over a bubbling cauldron with her black cat familiar at her side. Since most of the witches in these stories are women, it’s no surprise how the term ‘witch’ has become both a curse and a compliment – depending on your stance on feminist issues.

For a long time, though, the fictional witch was mostly bad, and the poor women who were actually accused morphed into the image of the ugly old hag who wanted nothing more in life than to destroy the happiness of the normative righteous. Although the fairy-tale witch with her crooked nose has often been deemed a negative female stereotype, I’m not entirely willing to dismiss her. In fact, I find her inspirational. That old woman with her herbs and spell books won’t be easily fooled by glitter and flattery: she knows people’s hearts and how to bend them. And maybe, just maybe, in a world of followers, hashtags and likes, her gritty, down-to-earth wisdom serves a purpose.

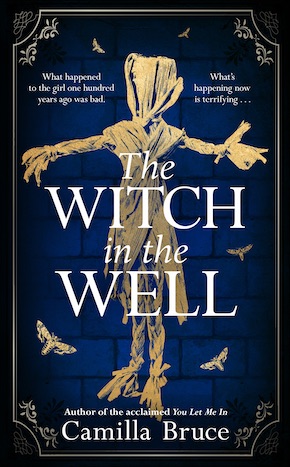

My own witchy offering this year, The Witch in the Well, is a quilt of the witches above. The novel is about two authors who want to write about the same historical witch trial, but come at it from two different angles. One wants to write a novel about a woman who is innocently accused, while the other believes the woman in question was in fact a witch, only a nice one. Trouble ensues when the two authors’ worldviews collide, and it becomes increasingly clear that neither of them got it right.

The witch trials aside, there has always been a strong link between women’s work and magic.”

The Witch in the Well was partially inspired by actual witch trials – or by the unfortunate women who weren’t benevolent midwives or healers, but were accused just for being unpleasant. Back in the day, it was considered extremely uncouth for a woman to run her mouth, and if she happened to argue with a neighbour – and the neighbour’s cow fell ill – a witch accusation might follow. I became fascinated with this ‘imperfect victim’ type of historical witch, who was probably not much liked in her community, and figured it was a category of accused that was unlikely to have been widely explored in fiction. Mostly, though, The Witch in the Well is about the mythical witch, in all her powerful glory, and the chaos that might follow once she is unleashed.

Some critical voices have pointed out that the current flowering of witches in books and on the screen might strengthen the toxic narrative of women as unstable and irrational, but I don’t think that is the case. On the contrary, I think the reason for the witch’s new popularity is that she has become an empowering figure who gives strength to traditionally female traits – like intuition and creativity – without devaluing them. The witch trials aside, there has always been a strong link between women’s work and magic, from small rituals performed in the intimacy of the kitchen, like the blessing of a bread, to mightier expressions, like the Norse sorceress, the Völva, who entered a trance guided by her distaff, an ancient spinning device. Perhaps this link came to be because women’s chores so often evolved around creating something new from base ingredients, like wool into garments and flour into food, but whatever the cause is, I happen to believe that it is something to celebrate rather than dismiss. Because, at its core, witchcraft is an act of creation, but instead of knitting socks or weaving cloth, it is the world that is the subject of transformation – and what can be more powerful than that?

—

Camilla Bruce was in born central Norway and grew up in an old forest next to an Iron Age burial mound. She has a master’s degree in comparative literature and has co-run a small press that published dark fairy tales. Her first novel was the acclaimed work of folk horror, You Let Me In; followed by the historical crime novels In the Garden of Spite/Triflers Need Not Apply and All the Blood We Share. She currently lives in Trondheim with her son and cat. The Witch in the Well is published in hardback, eBook and audio download by Bantam Press and Transworld Digital.

Read more

camillabruce.com

@millacream

@transworldbooks

Author photo © Lene J. Løkkhaug