Ann-Helén Laestadius: Lost lands and lost lives

by Mark Reynolds

Ann-Helén Laestadius’ Stolen is a forceful story of a young Sámi woman battling to preserve the lifestyle and traditions of reindeer herders in Sweden amid a wave of torture and massacre of the animals on whose livelihood they depend. At the age of nine, Elsa witnesses the aftermath of the brutal killing of her favourite calf by a notorious local hunter. Initially silent about what she has seen, she’s eventually taken by her father to report the crime to the police – but they are met with cold-hearted indifference. For the Sámi, an attack on reindeer is an assault on their culture and spiritual beliefs, but the law views the disappearances as a minor theft, which the police are unwilling to investigate.

Ten years later, at the annual Jokkmokk Winter Market, Elsa runs into old school friend Minna, who is studying to be a lawyer. Although Minna is more conflicted about her Sámi heritage than Elsa, the two team up to fight for justice, and for the killings to be understood as hate crimes.

Ann-Helén, who grew up among reindeer herders in the north of Sweden, and is of both Sámi and Tornedalian descent, has built a career as a journalist and author around her passion for standing up for minorities. Stolen is her first novel to be translated into English and the first in a planned trilogy, and her work is now set to find a broader audience than ever as a Netflix adaptation of Stolen goes into production. I catch up with her via Zoom from her home outside Stockholm, just as the second book in the trilogy is released in Sweden.

Mark: How has your dual Sámi and Tornedalian identity affected your worldview through childhood and in your adult life?

Ann-Helén: As a child, I was very close to my Sámi heritage, and recently I wrote a short story about my life and how I feel about being both Sámi and Tornedalian, and it was the first time I started to think about how I always viewed my father. I never, as a child, saw him as Tornedalian, I saw him as a Swede. And it’s kind of strange because my father speaks Meänkieli and I knew the language wasn’t Swedish, but still for me the two different cultures were Sámi and Swedish, which I used as a kind of protection. It was really hard to be a Sámi when I grew up in Kiruna in the 70s and 80s, the Sámi children were bullied and had a really hard time, so when I started school I didn’t want to tell anyone I was Sámi.

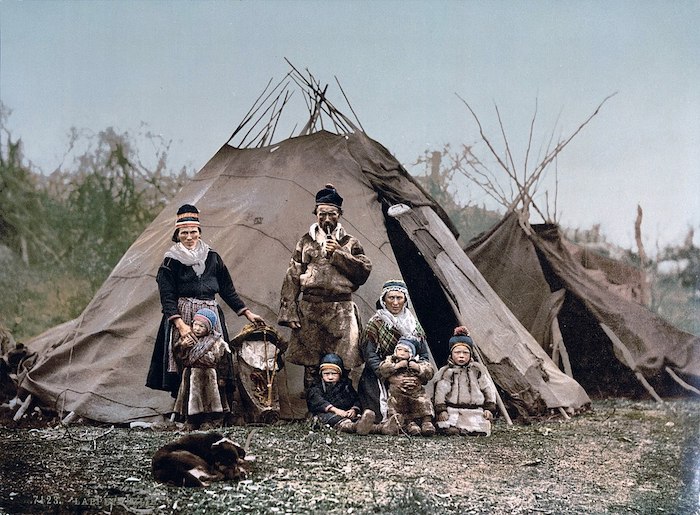

The older I got, the more I started to think about why I didn’t want to let anyone know about my Sámi roots as a child. But this wasn’t unusual, many of us growing up in the 70s and 80s were afraid to tell anyone about our background. Neither my mother nor my father let me speak Sámi or Meänkieli, they didn’t teach me. And for my mother’s part it’s because she went to the boarding schools – in Sweden they took the reindeer herder families’ children to boarding schools when they were seven years old, where they could no longer speak their language, and they were taught to be ashamed of their culture and background. As a consequence, when they grew up and had their own families, they didn’t want their children to learn Sámi because they were afraid they would be affected in a bad way.

Today of course I’m absolutely confident with my identity, and have been for many, many years. This turned around when I was seventeen, eighteen years old, when I started to talk about who I was and I went to courses in Sámi and I really tried to embrace it again. But it was strange because at home my mother spoke the language, all my cousins, my grandmother, grandfather, we had the Sámi Duodji, the Sámi handicrafts, my cousins and uncles were reindeer herders, so I had everything, but in school I had to be someone else. But that’s why I’m writing books, because this has really impacted me so much. I have thought about it the older I got, and as an adult I really knew that I wanted to write about this, and the consequences it has had for us.

In Sweden, the Church has asked for forgiveness for all the things they have done to the Sámi people. The government has still not done this… I would say Norway is much better at taking care of its indigenous people.”

How have Sámi oral storytelling traditions informed your own writing?

Oh, very much. My mother always told me and my sister stories as we were growing up, stories from her childhood, but also more supernatural things, about creatures in Sámi mythology. So from an early age I was taught not to follow anyone calling for me in the woods because it could be dangerous. These stories really made a big impact on me, and I knew that I also wanted to tell my own stories. I’ve been writing my own stories since I was six years old, and I knew that someday I wanted to be an author and a journalist. And my mother still tells me stories and reminds me of things that I should be writing about.

The territory of Sápmi extends across the national borders of Sweden, Norway, Finland and Russia. How does it affect Sámi identity today to be seen as a minority in their own lands?

Well I don’t know that much about Russia, but I do know that if you compare the four countries, Norway is the one that has come the furthest. They have many more books in Sámi, they translate a lot of books into Sámi, so they are pretty much ahead of us in Sweden and Finland. The Sámi in Norway have a better opportunity to put out their work. In Sweden, the Church has asked for forgiveness for all the things they have done to the Sámi people. The government has still not done this, so we’re awaiting that. Things are beginning to happen in Sweden too, but I would say Norway is much better at taking care of its indigenous people.

How frequent are the reindeer killings and torture – and a lack of police investigation – at the heart of the novel? And are these episodes over yet?

When I decided to write this book – I started thinking about it seven years before I wrote it – I started to collect stories from reindeer herders and my own relatives, who told me about and showed me pictures of the reindeer they had found dead or almost dead, tortured, and then I interviewed other reindeer herders and I met this young woman, Sara Skum, who gave me one hundred police reports that her Sameby, the Sámi village where they have their reindeer, had submitted for the last ten years or so, and the police hadn’t done anything about any one of them. All the cases were made known, but no one was doing anything. And this is still going on; I’ve seen pictures just this last week of reindeer being killed. But there has been some attention on this, which has put the police on the spot. TV4 made two programmes, and they confronted the police and showed them some of the police reports I also had the opportunity to read. So when this happened, and my book came out in Sweden, there was a lot of attention. And when some reindeer were found out in the woods outside a little village about 250km from Kiruna, the police actually took a helicopter to go and see, which has never, ever happened before, so I was really pleased to hear that. So maybe things are changing, but it’s still a crime that the police don’t put any bigger effort into, because of the low penalties. It’s only considered as a theft.

This is the first time you’ve switched from writing YA fiction. Why did this book demand an older, broader readership, and how did your journalism inform the telling of this story?

I thought it would be maybe too scary and I’d have to hold back if I made it another YA book. But I still wanted a child’s story, so I went to Elsa as a nine-year-old to tell the story from a child’s perspective, because I think it’s important to understand that it really affects the children in reindeer herder families, and how hard it is for the parents to tell their children what they are facing. But I didn’t think it was any problem to switch to writing for adults. I felt more free to write as I wanted to. My background as a journalist always helps, and it was important when I did my research and I met with the reindeer herders, and read the police reports. My experience as a reporter helped me a lot in the writing.

Do you identify more closely with Elsa or the relative outsider Minna; or do they both contain many aspects of your own character?

Well I wasn’t brought up in a reindeer herder family, but my mother was. But that was one of the things that worried me a bit when I started thinking about writing this book: I’m not a reindeer herder, can I tell their story right? So I did loads of research and talked to them a lot, and I also let the reindeer herders read my script before it was a book. So I would say I’m not Elsa, but I know a lot of Elsas. The inspiration comes from some of my cousins, and very much from Sara, as I got to know her. And Minna is a character who has been fighting a little bit with her identity, because it’s hard sometimes in the Sámi community to be accepted, and that’s one of the topics in my book too. Elsa’s mother Marika is considered a non-Sámi woman, although she is a Sámi. So I would say I feel some resemblance to Marika, because I have a father that isn’t Sámi, and in the beginning when I started to write books some people would come up to me and say that I’m not a true Sámi, you have to have both parents to be a Sámi. And there’s also a common belief in Sweden that you have to have reindeer to be a Sámi. So I would say Marika maybe, and Minna, I like her fighting spirit and I like the way she goes about it through the law. But I’m also like Elsa when it comes to not being afraid to speak my mind. So I think there’s a little bit of me in each of those characters.

In the northern parts, where I come from, it’s still quite traditional, but I see my cousins who are such tough young women fighting for their place in the reindeer herding, and it is easier nowadays for the women to join in.”

Elsa is determined to be out with the reindeer, which is unusual for a young woman. How have women’s roles in Sámi society today changed since your parents’ and grandparents’ time?

I’d say it’s different, depending on which part of Sápmi you’re talking about. In the south, the women have a bigger chance to take their place in the Sameby and have the right to vote, and all the family is involved in the Sameby in some way. Most of the time it’s just the men who can vote, but in the south they have seen a change. In the northern parts, where I come from, it’s still quite traditional, and mostly it’s the sons who follow their fathers into reindeer herding. But I see a change also up there, I see my cousins who are such tough young women fighting for their place in the reindeer herding, and it is easier nowadays for the women to join in, we have a lot of technical equipment that is a big help. It used to be very heavy work, you have to be physically strong to be a reindeer herder, but now we have the snowmobiles and helicopters, there are all sorts of things that make it a little bit easier.

There’s a moment early in the book where Elsa shouts up at the Northern Lights and she’s told off by her grandmother. What are traditional Sámi interpretations and beliefs about the Northern Lights, and how do these differ from how the phenomenon is marketed to visitors in the name of ecotourism?

This scene in the book is taken from my own childhood. When I was a little girl I was out with a friend in the playground outside our house in Kiruna, lying down in the snow making snow angels, and we saw the Northern Lights above us and we started to shout, like Elsa shouts in the book, “Hi, guovssahasat! I hear You!” And then my mother came out on the balcony in panic: “Stop shouting, you can’t shout. Come in, come in immediately!” She was so scared, and I was like, what just happened? And she didn’t explain then, she just said when I came in, “You cannot do that. It’s dangerous to be speaking to the Northern Lights.”

My new book, Straff (Punished), is coming out in Sweden now, and I write about it in there too. I talked to a lot of Sámi people and asked them what they knew, and everybody had some kind of story of their own. Some people think it’s a kind of warning, others say it’s dead people up in the Northern Lights sending some kind of message. Someone told me that a boy had pointed at the Northern Lights and then got his finger crushed shortly after. So there are different stories.

Now the Northern Lights is such a big thing, tourists come to Kiruna and they go up to Abisko and they’re so fascinated about it, which is good for tourism up there. I’m not afraid of the Northern Lights, but I still respect it like my mother taught me since I was a child. And I think many Sámi people, especially the older generations, believe it’s something to be quiet around. And I think most of the tourists respect it too.

In a similar vein, the Jokkmokk Winter Market dates back many centuries. What are your thoughts about the present-day commercialisation of Sámi handicrafts and associated activities such as snowmobile safaris and dogsled trails?

In the book Elsa is pretty upset when people come up to her wanting to touch her and take pictures, and that’s also something I’ve been through. When I’m here in Stockholm, sometimes I wear my gákti, my Sámi costume, and almost every time if I’m standing waiting for a bus or in the subway, someone comes up to me and says, “Do you need help? I can show you the way.” They just can’t imagine that a Sámi is living in Stockholm. So I’m quite used to the fact people don’t know about us, and it’s a big ignorance, actually.

It’s good that our handicrafts and the culture are widely spread, but it’s important that it’s made by the Sámi, I don’t like when other people make things and say it’s Sámi-made, it’s important to keep it in our community. I have relatives who do these tourist things, let people follow them out to the woods to see the reindeer and go on snowmobiles and eat out in the summertime, and many reindeer herders need the extra revenue, because it’s hard to survive on only herding.

But I think I’m right in saying there’s no Sámi tradition of dog-sledding.

No, nothing. I have no relatives who go out with a dogsled. The dogs they use like sheep dogs, for rounding up the reindeer.

I’m extremely happy that Netflix wants to make something out of a Sámi story, it’s very important for us to get our stories out in the world, so it will be good for the world to see what is still happening today in Sweden.”

What have been the most troubling effects of climate change on herding traditions and practices; and on the reindeer themselves?

My cousins have for many, many years now told me there’s a lot of problems, mainly for the reindeer to get to their food beneath the snow, because of the weather. First there’s a little bit of snow, and then all of a sudden it’s warm and it starts to rain and that forms a layer of ice, then another layer of snow and ice, and eventually the reindeer can’t get through this, and then the herders have to buy feed. It’s something that has truly exploded, it’s very expensive, and it’s a way of reindeer herding that many of them really don’t like – they want to be out in the free and let the reindeer follow their own path. But because the reindeer think it’s spring, they think now it’s warm, I have to go, they start to walk to the mountains, and it can be months before the real spring is coming. So that can get very troublesome and they have to keep them in place in a corral.

There is a high rate of mental illness and suicide among the reindeer herders. What are the main causes and effects? Is the outlook improving or worsening in recent times?

Every Sámi knows someone who has committed suicide, either a relative or a friend. When I started to think about writing this book, two cousins of mine, young men, had committed suicide. I was so upset, so sad, and I thought a lot about the silence in Sápmi – people don’t talk about their feelings or how they’re coping with all the problems they encounter. Especially the young men, they have to be so strong, they have to be so macho and they’re not supposed to speak about their feelings, and this is a big cause of mental illness. In my new book I write about how many of the people who went to the boarding schools don’t want to tell their children or grandchildren what they’ve been through because they want to protect them. And for my own part I didn’t dare ask my mother what she went through, because I was afraid of what I’d hear. So it’s from both sides. But I think the silence is very dangerous and is affecting us in a bad way. I don’t have the latest statistics, but there have been a lot of suicides for many years now. Things are getting better because of SANKS, the medical clinic in Norway where you can go and get help in your own language, which means a lot. The doctors and therapists know your background, and understand where you’re coming from. Because Swedish doctors don’t have a clue about how it is to grow up with this hatred and pressures from the mines, the forest companies and the rest. But I have a lot of hope in SANKS, and they are now also starting here in Sweden, so I hope it will be better here. But it’s tough, it’s hard. Traumas are passing through the generations.

Stolen is the first book in a planned trilogy. What readers can expect from books two and three?

Book two, Straff, is about five reindeer-herding children who have been taken from their families at seven years old, and you get to follow them in the boarding school, and then thirty years later, in the 80s, in the villages in and around Kiruna, and see how they were affected by the things they went through as children, and how they’re trying to cope. It was a very hard story to write, but also good because it finally made me and my mother talk about things we hadn’t spoken of before, and we went through her photo albums and I got to see pictures of her in school. The third book is still a bit of a secret, I don’t want to tell too much but I do have a plan and it’s going to be in the Sápmi community, but more than that I can’t tell you yet.

How closely did you work with Rachel Willson–Broyles on the English translation of Stolen?

She emailed me sometimes with specific questions. She wanted get all the details right about Sámi life, and that made me very confident it would be a good translation. I got to read the script too, which was fantastic. To be out in the English market is like an author’s dream in Sweden, so I’m so happy about that.

How involved are you in the Netflix adaptation, and what’s the timeline for its production and release?

They are starting filming now, in February, and they let me read the scripts. I’ve had the opportunity to follow the work with the scripts step by step, and I’m extremely happy that Netflix wants to make something out of a Sámi story, it’s very important for us to get our stories out in the world. You know, Sweden is always bragging about being such a good country, but they don’t take that much responsibility for the things they have done to the Sámi people, so I think it will be good for the world to see what is still happening today in Sweden.

It seems to be in the hands of the perfect director in Elle Márjá Eira, who sounds like a force of nature.

Yes, absolutely. Elle Márjá Eira is great, and Peter Birro who’s writing the script is also fantastic, so I think we’re a good team and everybody is really listening to each other.

Which other contemporary Swedish or Scandinavian writers would you strongly recommend?

There are some really exciting new Sámi writers. One of them is Ella-Márjá Nutti. I don’t know if it’s translated yet, but she has written a very touching novel Kaffe med mjölk (Coffee with Milk) about a mother in a Sámi family who has cancer – and there you have the silence again. She’s really good, and also another new writer, Tina Harnesk, whose book Those Who Sow in Snow is going to be translated in many languages. There’s been a big change, there are so many Sámi writers coming now. When my first book came out in 2007 I went to the Gothenburg Book Fair, the biggest book fair in Sweden, and I was the only Sámi writer there, and now there are lots of people coming to the book fair to talk about their books, so I see a bright future for Sámi authors.

Which authors did you read as a child that most inspired you to write?

One Swedish author, Maria Gripe, wrote books that are really close to me, and sometimes had supernatural themes, which came back to my own childhood and the stories my mum told me. But I also liked the Nancy Drew mysteries, which were considered bad literature in the 80s but we loved them. Anne of Green Gables was also a favourite.

Finally, what do you plan to write next? Is there anything else coming before third book in the trilogy?

No, the third book is my main goal now, but it has been really busy since Stolen came out, I’ve been working so much with that. When I went home in summer 2021 after the pandemic had cooled down a little bit I finally had the opportunity to write the second book. And now with the launch in your country and the States and in Canada, and more countries coming later this year I have a lot of work to do. I also need to take some time off, I need to breathe a little bit so I can start to write again. I need to go home more, I need to be out in the forest, I need to go fishing for salmon and just be cool. Here in Sweden in was two years between the first two books, so maybe it will be another two years before I publish the third.

—

Ann-Helén Laestadius is an author and journalist from Kiruna, now based in Solna outside Stockholm. She has written two children’s books and seven YA novels, including Ten Past One, which was awarded the prestigious August Prize for Best Young Adult and Children’s Novel and the Nordic Literature Prize. Published in Swedish in January 2021, Stolen became a number one bestseller and won the Book of the Year Award, the Adlibris Award for best novel, and the Your Book Our Choice Prize, given by the Swedish Association for Bookstore Employees. Stolen is now published by Bloomsbury Circus in hardback and eBook, translated by Rachel Willson–Broyles.

Read more

@AHLaestadius

@BloomsburyBooks

Author photo by Thron Ullberg

Rachel Willson–Broyles majored in Scandinavian Studies at Gustavus Adolphus College in Saint Peter, Minnesota, and received her BA there in 2002. She started translating while a graduate student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where she received a PhD in Scandinavian Studies in 2013. Rachel lives in Saint Paul, Minnesota. Her other recent translations include Beyond All Reasonable Doubt by Malin Persson Giolito, The Helios Disaster by Linda Boström Knausgård, Sweet Revenge Ltd by Jonas Jonasson, The Survivors by Alex Schulman and Blaze Me a Sun by Christoffer Carlsson.

rachelwillsonbroyles.com

@rwillsonbroyles

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.

@bookanista

wearebookanista

bookanista.com/author/mark