Christina Patterson: Five lives

by Mark Reynolds

“A memoir full of wit, wisdom, tenderness and heart. Christina Patterson writes so beautifully, and with searing honesty.” Dr Rachel Clarke

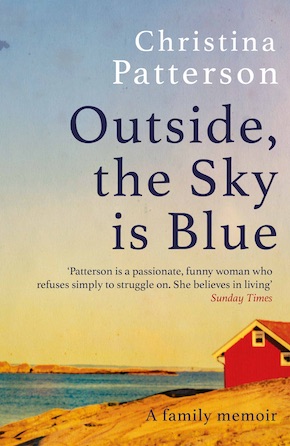

When her brother Tom died suddenly at the age of 57, it fell to Christina Patterson, as the last surviving member of the immediate family, to clear out his house. She diligently sorted through the papers Tom had gathered, including all manner of diaries, letters and photographs left by their parents and older sister Caroline. The resultant book Outside, the Sky is Blue picks out fragments of those documents and the memories they trigger for Christina in a tender, candid, sometimes heartbreaking, ultimately joyful account of family life, overcoming illness and loss, and embracing happiness.

It all begins with her parents John and Anne’s ardent courtship and early years of marriage, when John served as a diplomat in Bangkok and Rome, before moving their young family to suburban Surrey. John commuted to a new job in Whitehall while Anne worked as a primary school teacher, and each year the family would undertake a long journey by car and ferry to Anne’s native Sweden to spend their summers.

Both Tom and Christina sailed through school with top grades, but Caroline fared less well. Always highly strung, Caroline suffered a nervous breakdown in her teens and was diagnosed with schizophrenia, which would hamper her ability to hold down a job in later life.

Around the time of Caroline’s diagnosis, Christina began attending a youth club run by evangelical Christians, and got so swept up in their teachings that within a few weeks she was converted from a passionate atheist into a fundamentalist whose first aim in life was to please Jesus. Astonishingly (and Christina herself is astonished by this, looking back), this commitment would last well into her twenties, and became a crutch to help her through debilitating bouts of an illness that was finally diagnosed as lupus. It also led to some regrettable life decisions that interfered with her deeper longings for romance and travel as she set out on a career in publishing, literature and journalism.

I spoke to Christina, on what it turns out would have been Tom’s 60th birthday, about putting the book together during the pandemic, her feelings of Swedishness, Caroline’s mental struggles, how her two brushes with cancer opened her eyes to a crisis in nursing, about finding a partner and buying a new bolthole together in Umbria, and her feelings towards authority figures from God to Boris Johnson.

—

Mark: Your family amassed a remarkably thorough archive of letters, diaries, photographs and cine films. Was your mum archivist-in-chief, or is it a trait that runs right through the family?

Christina: She was definitely archivist-in-chief, yes. But I have to say my Dad was pretty good as well, he had loads of quite neatly labelled albums, and they both wrote diaries for their entire adult life. My sister was very good with photo albums, and my brother had quite a few as well. It’s ironic that it’s me that’s ended up writing the book, because I’m absolutely the least organised. My mother’s the one who had the full archive of my published journalism, and of course that’s completely gone to pot since she died, so I’ve got nothing now except links you have to subscribe to, to read. I really don’t know why she was so organised in that way, but she was and I’m absolutely not.

Was Tom’s sudden death the catalyst for this book, or were you already planning a family memoir?

I’ve been planning to write a version of it for twenty years, actually. The original thinking was about my wacky born-again-Christian years and my sister’s breakdown and schizophrenia, and the quite probable but unprovable link between those two things – how one person’s pain and suffering affects another person’s life. I had this weird and embarrassing illness in my twenties which came back in bursts of crippling pain, and it was embarrassing because it was inexplicable. I can’t prove it, but I think there was some link with Caroline’s illness.

So I suppose I wanted to make sense of all of that, and then it was just extremely unfortunate that, one by one, they died. Tom had always said fine, go ahead, write what you like, but when he died I seriously thought I might not be able to do it. It was only when his best friend Stuart told me I should write the book that I felt in a way I’d been given permission from his representative on earth. It sounds like a ridiculous thing to say, but they were friends from the age of eleven, and best friends to the day Tom died, so it really did feel like being given permission by his representative on earth to go ahead and write it.

Click on images to enlarge and view in slideshow

So where did you start, with all the sifting through…?

So where did you start, with all the sifting through…?

I think for journalists, the leap from 800, 1,200 words, even two-and-a-half, three-and-a-half thousand words to a hundred thousand is a nightmare. Once you’ve got the structure, it’s kind of fine, but finding a structure for this book was a challenge, because essentially I had five people’s archives – mine, as I’ve explained, was utterly chaotic and basically just scattered around my home, but I had five people’s photos and papers and albums; five people’s lives that needed to be somehow interwoven into something coherent and, one hopes, entertaining. I found it really, really difficult, and in the end I just had to do it chronologically.

This was quite a project to have been tackling during lockdown. Were you spending a lot of time just on your own with all this stuff?

Yes, but then I’ve now worked at home on my own for ten years, so I’m used to it. Actually my partner’s just gone back to the office and I’m incredibly jealous because, you know, he gets chat! And lunch hours! I keep treating myself to really expensive local smoked salmon bagels and flat whites just to get out of the flat…

So it wasn’t particularly different to my normal working life, but obviously going through all those photos and letters was pretty poignant and painful, but then being in a state of grief about Tom’s death, I would have been thinking about all that anyway.

So what was the mix of catharsis and sorrow and despair?

Not much despair, actually. I mean obviously terrible grief when Tom died, but it’s interesting that I rankle at the word ‘despair’. Sometimes the grief felt unbearable, but it never did feel like despair. Because for me despair is the ultimate, really: I want to give up, I want to die, I’ve had enough. And I have had that in my life, but I haven’t had it since Tom died.

But grief, yes, obviously, a lot; catharsis, a huge amount. I have, as I say, wanted to write a version of this book for twenty years, and I don’t see a reason why anyone should inflict their cathartic therapeutic processes on the world unless it’s also something that’s enjoyable or entertaining – because the point is that there’s a contract with the reader, and your job is to give the reader a good experience. So it’s kind of a by-product in a sense, but there definitely was huge catharsis, and now that I’ve physically got the book in my hands, I do feel like, oh, phew, I’ve done it. This has been hanging over me, and I’ve done it now.

Back then, there was no kudos at all in not being English-English and suburban. My sister was desperately embarrassed, she just wanted to be the same as everyone… but Sweden was quite an important part of our lives.”

In your childhood, ABBA’s Eurovision success was a joyful moment shared with your Swedish cousins. How Swedish did you feel growing up in Surrey?

Funnily enough, I was at a party for the editor of the Jeremy Vine show – they have me on a lot, for a bit of Boris-bashing, basically – anyway, he just retired and he had an ABBA tribute band at his leaving do, and when they struck up with ‘Waterloo’ I felt like saying, “Hey, I discovered ABBA before anyone else! I’m the one who had their posters all round my bedroom!” I even had ABBA: The Soap and all the rest of it.

But we never really felt Swedish – and we felt very, very English when we went to Sweden. I loved the Swedish stuff, but no one had even heard of Sweden really when we were children, not before ABBA came along and then Björn Borg, IKEA and all these things (I’ve had to train myself to call it ‘eye-key-ah’, because it’s ‘ickier’ in Swedish. I’ve been going there since I was a baby, and I still love it).

But we never really felt Swedish – and we felt very, very English when we went to Sweden. I loved the Swedish stuff, but no one had even heard of Sweden really when we were children, not before ABBA came along and then Björn Borg, IKEA and all these things (I’ve had to train myself to call it ‘eye-key-ah’, because it’s ‘ickier’ in Swedish. I’ve been going there since I was a baby, and I still love it).

So I felt a bit Swedish, but also just sort of slightly embarrassingly different, in a sense. Back then, there was no kudos at all in not being English-English and suburban. My sister was desperately embarrassed about it, she just wanted to be the same as everyone, she never used to talk about Thailand where she lived or Italy or Sweden, or any of this stuff, but it was quite an important part of our lives.

Why do you think you became so transfixed by evangelical Christianity in your teens and twenties? Is the way they operate designed to get under your skin? I genuinely felt like punching the air at the point where you write “Fuck off, God” in your diary.

Funnily enough, I recently reviewed a book for The Sunday Times called Beyond Belief by Elle Hardy, about Pentecostalism and the huge rise in the so-called charismatic movement in the 70s which came out of America, and that’s what I got caught up in. So it was even more wacky than your bog-standard Baptists, who one would think of as kind of po-faced and grim, whereas this was actually very exciting for a fourteen-year-old. You know, lots of handsome boys in leather jackets, all speaking in tongues and proclaiming that the Lord Jesus was their saviour. Unfortunately it proved to be a heady combination.

It’s difficult in these times to speak negatively of religion, because we’re all meant to be tolerant and so on, but I think fundamentalism is a very bad thing, and fundamentalism was a very bad thing for me.”

But it absolutely is designed to hook you in. In a sense, all the devices, all the apps, anything we’re hooked on is of course designed to do the same, whether it’s the sugar-carbohydrate combination in Kettle Chips or the dopamine hits of the version of Christianity I was sucked into. It was very emotional, in a way quite narcissistic or solipsistic, because it was very much about you and your personal relationship with God, and people believing that God was in control of their lives to a really minute degree, giving them parking spaces, getting rid of their colds, all of this stuff, and I did get hooked in. And I do think it was kind of a tragedy. It’s difficult in these times to speak negatively of religion, because we’re all meant to be tolerant and so on, but I think fundamentalism is a very bad thing, and fundamentalism was a very bad thing for me.

There are many heartbreaking moments in the book, not least Caroline’s treatment by a succession of unsympathetic employers. Is the job market any kinder to schizophrenia sufferers today?

I really doubt it. I don’t know, because I’m not involved in the job market, but I think when all the millennials talk about mental health, they’re talking about something entirely different, and I don’t think many employers seriously engage with people with severe and debilitating mental illnesses. I may be wrong – I hope I’m wrong – but I don’t think I am. I think very few employers are prepared to cope, in a very competitive, cut-throat world, with carrying people who are dealing with these kinds of challenges.

A few years ago, I wrote a piece for the Guardian about a cafe in a basement in a church in Southwark for people with mental illness, and it was a very sad experience. Because I met these people, mostly they were middle-aged, they’d mostly had very difficult lives and very little in the way of employment, and I think many people with mental illnesses are condemned to a life on benefits, often in erratic housing. So I suspect that not much has got much better on that front, sadly.

To what extent do you think Caroline’s drug regime contributed to her heart problems, and to her death at 41?

Do you know, I don’t think we ever talked about that as a family, and we can’t know. But a drug that you take for thirty-odd years – slightly less in her case, because she was younger when she died – and the weight gain it causes, I just can’t think that’s a healthy combination, and my understanding is that a lot of people with schizophrenia do die quite young. So I’m sure there are lots of complicated factors, but I think it must have played a part.

Do you know, I don’t think we ever talked about that as a family, and we can’t know. But a drug that you take for thirty-odd years – slightly less in her case, because she was younger when she died – and the weight gain it causes, I just can’t think that’s a healthy combination, and my understanding is that a lot of people with schizophrenia do die quite young. So I’m sure there are lots of complicated factors, but I think it must have played a part.

You’ve suffered more than your share of debilitating health issues and ineffective treatments. Are you now a convert to holistic, alternative therapies, or is grabbing a handful of drugs sometimes the only answer?

No, I’m not a convert at all. I tried so many things, and most of them were a complete waste of time and money. I’m a convert to one acupuncturist who I see when I have a flare-up of anything, but I hardly ever see her these days. I’m dreading the day she retires, because she must be probably late-60s now.

Health and healing is such a complicated area, isn’t it? But I think clearly a kind of basically healthy life, i.e. work you quite like, not living with terrible financial worry, ideally having some love in your life, having friendships, eating relatively healthily, but most of all being fundamentally fairly happy, I think those are the things that on the whole are most likely to make us healthy. And if holistic treatments, by hook or by crook, or by placebo or whatever, manage to do that then fine, I’m all for them.

I do think we can overmedicalise a lot of things, and I genuinely think that shoving yourself full of lots of drugs is often not the best thing to do – though absolutely necessary if you have cancer or something like that. So I’m in favour of a holistic approach to health in the way I’ve just described, but I do think that an awful lot of alternative practitioners are essentially charlatans.

I found this therapist, Richard, who I write about in the book, and I will forever be grateful for what he did for me. If I hadn’t seen him, I very much doubt that I would have the stability and happiness I have in my life now.”

Your experience at Homerton for your first cancer operation was pretty dreadful. How did you prepare differently for the second operation?

The second one was at the Marsden and again I had a terrible, terrible time, but I didn’t want to go into all of that in the book. The surgeons were great, but the nursing was absolutely terrible, which is why I ended up doing a big healthcare campaign for the Independent and also for Radio 4 and various places. But one of the things I had to do to prepare, ironically, was fatten myself up, because they were taking flesh from my stomach to reconstruct a breast, and the surgeon said there wasn’t enough on me. So for the first time in my life I spent the next few weeks ploughing through five cakes a day – and amazingly, when you’re meant to do it, it’s not much fun! When you’re not meant to do it, of course, it’s absolutely wonderful. So that was the key thing I did to prepare.

But I was obviously very, very worried and upset, it was a dreadful time. And I found this therapist, Richard, who I write about in the book. I only saw him once or twice before I went into hospital, and then saw him afterwards, and I will forever be grateful for what he did for me. If I hadn’t seen him, I very much doubt that I would have the stability and happiness I have in my life now. I can’t imagine how I would have coped with my mother’s and brother’s deaths if I hadn’t seen him.

Aside from writing and editing the book during lockdown, what has a typical day looked like over the last couple of years, and how did you cope with adjusting to a life with fewer deadlines?

A typical day? Oh God, get out of bed, stare at your computer for 18 hours, get back into bed, do the whole thing all over again. I’m used to working at home, but I always had a very, very busy social life. For most of my adult life, I’ve been out most nights, and I have really missed that social interaction. I am seeing people now, but still quite cautiously.

The deadline thing is so interesting. If you’re a journalist, it’s so hard to galvanise yourself unless it’s a really real deadline. So basically my whole work life is a kind of gallop from deadline to deadline. I started a podcast during the first lockdown, and I’ve now done three seasons, and I really enjoy it but it’s extremely time-consuming. Not just researching, but doing the interview, editing, sharing on social media. The stuff I can’t stand, which seems to take up my entire life, is the non-writing – the endless admin, emails – the bollocks, basically. Sometimes I feel like my work life is just made up of the bollocks, and nobody even pays me for the bollocks.

Of course, being a completely free person it’s entirely up to me, so I don’t know who this imaginary boss is I’m blaming for my failed work life, but I find all that stuff really, really, really tedious. What I like is the actual thinking, the writing, the talking. I could chat and write till the cows come home, but all the rest of it, count me out, I wish I had teams of people to do it all for me.

It’s fair to say there have been atypical days during lockdown for you as well – like buying a new place in Italy, and having a tiny wedding. Is ‘Paradiso’ a ready-made home from home, or is it in need of a trip to IKEA?

We’ve only just completed on it, actually, and we saw it in the summer of 2020, so it’s been a ridiculously long time because of Italian bureaucracy. In fact we’re going over for the first time as owners in March, so that’s really exciting.

It’s not a major renovation project, but it’s barely been lived in for the last eight years, which is why it was such a bargain, so it needs a coat of paint and a cosmetic makeover, and the gardens are completely overgrown. But when I go to bed, when I finally put my devices down, that’s what I dream about, being out in Umbria, sipping wine on a terrace and all of that.

Do you plan to spend a good chunk of time there when it’s fixed up?

I would very much like to. Unfortunately Brexit hasn’t hugely helped on that front, because we are limited now, so although I can work anywhere, you can’t spend more than three months in six out there, so I’m going to have to think quite carefully about when to go. And my partner has this thing called a job, which apparently some people have, which means that he actually has some obligations to somebody else.

So we haven’t worked that out yet, I think it will be trial and error, but in my ideal life I’ll be out there a lot, writing books and sitting in the sunshine, because I hate the climate in this country, I really do. When the sun comes out, it’s lovely, but just the endless, endless grey and rain, it really depresses me.

And after the tiny wedding, are you planning a bigger celebration at all?

I don’t think so. I mean, the wedding was for a reason, it was for Umbria, and I never think of myself as married, and I never, ever refer to Anthony as my husband. So the tiny wedding was a lovely day, and a chance to get a very nice meal out when you weren’t allowed to go out for meals much. I don’t think we’ll do anything bigger, no. I did briefly think we might, but it’ll be so far away by then we’ll probably be divorcing by the time we get to do anything!

I think the number of deaths we have had is disgraceful. It’s hard to make an overall assessment until the pandemic is actually over, but we know that Boris Johnson said ‘Let the bodies pile high,’ and he did.”

At a risk of opening a vast can of worms, how would you summarise the UK government’s response to Covid, and Boris Johnson’s leadership in general?

Well, while I am personally very happy in my life now, I am in a state of – actually the word you used earlier, despair – about our political situation. It’s not just that I think Boris Johnson is incompetent and nasty and narcissistic – and sociopathic, actually, and I don’t say that lightly. It’s that he has wrecked faith in politics and politicians, and severely damaged the institutions of this country. And the fact that he regularly resorts to Trumpian tactics like his smear on Keir Starmer is a real nadir in British life. I know there are lots of so-called metropolitan elite ‘remoaners’ complaining about how awful it is to be British these days, and I was and am very upset about Brexit, not least because it wasn’t a cleanly fought campaign, but what’s happening now is a whole other deal. To be regularly, regularly lying in Parliament – just to be lying all the time – clearly this is a man who never, ever took the rules he imposed on the nation seriously, and I think the number of deaths we have had is disgraceful. It’s hard to make an overall assessment until the pandemic is actually over, but we know that Boris Johnson said “Let the bodies pile high,” and he did.

What puzzles me is the number of deaths they’re announcing every day with no explanation. It’s just become normal to expect 200, 300 deaths a day, and nobody knows who’s actually dying.

Exactly, completely normalised, no mention of the people who are dying, and Boris Johnson doesn’t want the figures to be public anymore, because he wants to pretend the pandemic is over, and tragically it isn’t.

And it’s reported everywhere using the same formula, with the proviso that some of the figures may not even be Covid deaths.

I know, and the other one that made me so angry from the start, which they used to use a lot, is ‘underlying health problems’. Most people in this country have an underlying health problem or two. We’re one of the fattest nations in the world, so of course there’s a huge amount of high blood pressure, diabetes, obesity, and just ageing – you know, we’re not superhuman machines. So I find that deeply, deeply upsetting and insulting to people, to suggest that if you’re in anything other than perfect health then you don’t really count as a death figure.

I’ve just got one final question, and I think I pretty much know the answer from what you’ve already told me. But, to borrow what you observe was always Caroline and Tom’s heartfelt conversation-opener, how are you?

Do you know, I’m fine. I mean, today is a poignant day for me because it’s Tom’s birthday, but fundamentally I’m fine, and I’m happy, I’m just incredibly grateful to be alive. I think it’s very, very sad that I lost my really special family. One of the reasons I’m so upset about the political situation is because they were all fundamentally extremely decent, kind, good people. I was brought up to believe that being a good person was the most important thing in life, and I believe that. Obviously we all fail on multiple fronts all the time, but I do feel very lucky to have had them as my family. I feel very lucky to be alive and in good health now. Obviously I wish we weren’t living through this absolute tragedy of a pandemic, and I wish we weren’t about to face the economic problems we’re about to face, but speaking personally, I’m absolutely fine, thank you.

Christina Patterson is a writer and broadcaster. She writes for The Sunday Times, the Guardian, The Telegraph and the Daily Mail, as well as magazines ranging from Harper’s Bazaar to Red. Her first book The Art of Not Falling Apart was published in 2018. She regularly appears on radio and TV news programmes, hosts the podcast The Art of Work and is a speaker, facilitator, conference chair and coach. A former columnist at theIndependent and Director of the Poetry Society, she has contributed to books on poetry, literature and health. Outside, the Sky is Blue is published by Tinder Press.

Christina Patterson is a writer and broadcaster. She writes for The Sunday Times, the Guardian, The Telegraph and the Daily Mail, as well as magazines ranging from Harper’s Bazaar to Red. Her first book The Art of Not Falling Apart was published in 2018. She regularly appears on radio and TV news programmes, hosts the podcast The Art of Work and is a speaker, facilitator, conference chair and coach. A former columnist at theIndependent and Director of the Poetry Society, she has contributed to books on poetry, literature and health. Outside, the Sky is Blue is published by Tinder Press.

Read more

christinapatterson.co.uk

@queenchristina_

queenchristinawriter

@TinderPress

Author portrait © Laura Pannack

Family photographs courtesy Christina Patterson

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.

@bookanista

wearebookanista

bookanista.com/author/mark