Trading places, writing stories

by Mika Provata-CarloneTrading places have very real symbolic, metaphorical and literal presence in the story of how we have united or divided, structured or wrecked our worlds across time. The words can mean a physical location where goods are traded, bought and sold; or, again, a place of enchanted objects, to be had for the asking (and for a price), a crucible of humanity full of stories of provenance, whiffs of mystery, undertones of danger, strangeness and allure, complex pleasures or adventure. It can mean a familiar space where needs are met, where difficulties are resolved, where the challenging becomes reassuringly easy, obtainable and convenient. Above all, trading places can represent the full semantic transitiveness and dynamic force of that highly active gerund, namely the process, conscious or unconscious, of transcending one’s comfort (or discomfort) zone in order to be translated to the condition and experience of another, of trading places with someone else in both figurative and in tangible, possessable terms and items. The trading of goods was always and fundamentally an exchange of cultural experiences, an exercise in willing or forced empathy or, if nothing else, approximation; it has been at the very least an encounter at a crossroads of a physical geographical space, or at a juncture of more conceptual, and radically transformative proportions. Enemies tame and acknowledge one another, even momentarily, through the trading of gifts, separating distances dissolve, at least in the mind, through the trading of unique, even if commodified, markers of identity; even the sense of individual or communal selfhood is often forged, established or confirmed through the differentiation or the amalgamation of traded goods within a new, distinctive narrative; more especially, stories, those fabrics of words, acts and interactions that weave our lives together in tangles or meaningful tapestries, are not infrequently born as a result of journeys on trading routes, or even shopping trips.

Back to the Shops is written with a gait, a lilt and a swagger that are rather captivating, resonant with a personal voice that inhabits both time and space, collecting and recollecting gestures, images, imprints and practices.”

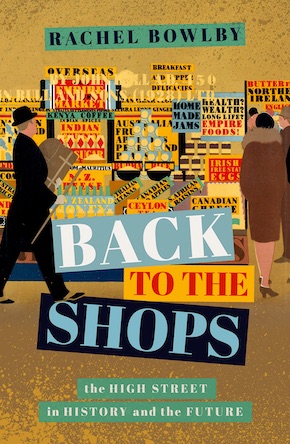

The trading of goods in the history of time and humanity has been more than just consumption, as the last few decades seem to suggest. It has been a cultural exchange with others, an exploration of the Other, a way of forging bridges where war or diplomacy had failed. For all that it has also been used as a political tool of dispossession or deculturation, of colonial aspiration or quite brutally of domination, trade and trading places, the more personal act of shopping and the relative private realm of shops, have been at the heart of our sociocultural becoming. It is a process that has fascinated Rachel Bowlby for a very long time, not merely for the sake of material culture, and the culture of materiality, the stuff that culture itself is made of, but especially for the promise it holds to tell the stories of places and people, to reveal places and people through the way the trading of goods and the places of trade have informed and inhabited the stories we tell of our world. In Back to the Shops: The High Street in History and the Future she brings the two strands of this fascination together, creating a plexus of commercial evolution and of literary representation, the trading of goods and words in turn. The aim of her book, as she says, is “to give some sense of the many kinds of businesses and building and human relationships that shops, in all their variety, have sustained and suggested” – and to do so with particular relish through the writings of authors who have also been her close companions for a very long time.

Back to the Shops is an ethnographical and sociological journey through the twentieth century, which is Bowlby’s main focus, with sharp, yet often longing backward glances towards the past for roots and antecedents, signs and portents. It is written throughout with a gait, a lilt and a swagger that are rather captivating, resonant with a personal voice that inhabits both time and space, collecting and recollecting gestures, images, imprints and practices as it does so. The focus on the twentieth century belies Bowlby’s interest in a democratised materiality, in a communal experience of the transcendental or the mundane aspects of trading places. It also speaks of the difficulty in tracing a history of shops proper, as opposed to workshops, where what was made was sold in situ, and of her chosen theoretical framework, namely to make a distinction between the shopping practice and the more oral or anecdotal history of the general population, and the equivalent traditions and rituals of the wealthier classes, where records and evidence are more substantial, not only in terms of what aristocratic households purchased, say at fairs, on exotic trips, or through purveyors, but also in terms of what they themselves sold as products of their lands, their estate, or their later bourgeois trading specialisations.

Shops for Bowlby emerge not only as the containers of goods, the platforms where they pass from one hand to another, but as being also important in themselves as a marketable element of that other new commodity, the “experience of shopping”. They acquire character and a certain iconicity from the eighteenth century onwards, when the term “going shopping” as opposed to “doing the shopping” seems to have been coined for the first time. She is interested in evolution and circularity, in utopias and atopias: if cities at first emerged radially around trading places (market centres and trade roads), superstore “shopping centres” built outside city centres, are the “centres of nowhere”, whereas “the story [of shopping] can be said to have come back to its point of origin. In the beginning, the not-yet-shop was the pedlar’s pack; inside it the rare thing that came to the customer once in a while. And at the end, the no-longer shop is the smartphone, offering all the commodities that money can buy.” Between these two extremes of planetary motion over the course of centuries, lies “the fixed, located space of the shop that a customer comes to and a shopkeeper keeps.”

Bowlby has a talent for words, for the world of associations and images that they can conjure and retrieve, for the incisiveness with which they can allow a mind like hers to read each step along the human journey of shopping and trade, and more broadly of what she defines as that human community of change, encounter and exchange, on a narrative, conceptual or socio-material level. She sets out to delineate three “supra-categories”, namely the settings, roles and specialities that can demarcate shops and the shopping experience, and to reveal the role of shops and shopping for contemporary societies through historical records, sociological studies, and above all literary tales and the fates and lives of the characters who inhabit them as these are fleshed out through shops and shopping. She will talk both about small, distinct, individual shops, and about shopping megatheria and store chains, which she considers an unfortunate misnomer, since “the structure implied is one of spreading out from a primary point of beginning” – whereas for her the image should be closer to a tree, to echo the term “branches”. Chain stores are at least terminologically American, the British antecedent being called a “multiple”: “for some reason, that useful term was gradually taken out of service, in favour of its clanking alternative.”

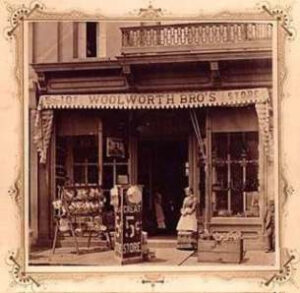

If your idea of chain stores evokes mass production and blandness, Bowlby begs to differ, at least as regards the first stages of the phenomenon. Chain stores such as the Co-op emerge from her analysis as agents of social change and equality in newly-built industrial towns, where a shop owned by the factory proprietor could impose a debilitating monopoly on local buyers (i.e. the workmen and their families). Chains meant standardised, universal, “democratised” prices, as well as quality, some semblance of transparency in living costs, an interesting case of “tables turned” when considered against the current trend of “small shop” gentrification. “The cooperative model became” – counter-intuitively, it would seem today –“hugely influential as a model for a non-capitalist means of distribution”, garnering the support of “intellectuals such as Beatrice and Sidney Webb and Leonard and Virginia Woolf” no less. It also contributed to women’s emancipation, and greater sense of agency. It would be Émile Zola who would graft the term “democratisation of luxury” into everyday social speak, and George Eliot who would demonstrate that “when it comes to commercial, rather than theological [or ideological] loyalties, trade trumps religion [and politics] every time. And the word [for] this distinction is convenience.”

The story of such megagiants of convenience as Tesco, Woolworths, Selfridges, Sainsbury’s, the Co-op or Boots the Chemist is the story of human bodies, of new bodies, old bodies, somebodies and nobodies.”

Convenience meant that one could be in control of one’s own purchasing power, determine the process, rather than be determined by or excluded from it. It would lead to both nirvana states and dire disasters, to dramas like Madame Bovary’s, or to female empowerment, such as Eliza Doolittle’s. The story of such megagiants of convenience as Tesco, Woolworths, Selfridges, Sainsbury’s, the Co-op or Boots the Chemist is the story of human bodies, of new bodies, old bodies, somebodies and nobodies, as defined by shopping, the experience of shops, and that new space and gesture of existence. Bowlby has a “shopping spree” of her own through her book, “sampling” from a veritable emporium of authors, from Henry James, George Eliot, H.G. Wells, Shirley Jackson, Thackeray, Samuel Pepys and Charles Dickens, to George Gissing’s landmark New Grub Street and George and Weedon Grossmith’s The Diary of a Nobody. To these she will add the company of William Hazlitt, Balzac, Orwell, Arnold Bennett, Jane Austen in her full glory, Shakespeare and William Wordsworth, William Cowper, Fanny Burney, Rudyard Kipling and Elizabeth Gaskell, Chaucer and Madame de Lafayette for a sense of historical depth and perspective, Samuel Beckett and James Joyce for their critical angle and their peerless inscribing and analysis of societies and individuals. Throughout, readers will also think of Michael Bond’s Paddington, Paul Morand’s men in a hurry, or Valery Larbaud’s multimillionaire Barnabooths, all in search of that summum bonum, the good and happy life, or the perfect duffle coat…

Across pages of shopping in novels or the records and chronicles of real life, Bowlby will seek to address questions of cosmopolitanism and insularity, ecumenism and isolationism, consumerism, fast fashion, universalisation and a connected world community. She will also tacitly point out the subtext of any shopping narrative as pursued from the vantage point of twenty-first-century society, namely that of an urbanised, fundamentally alienated or at least globalist perspective (one experience fits all), in an essentially decultured, or un-differentiated (undiversified) world. This surfaces more poignantly in the textual engagement with the hyperbole and euphemism of market spaces and marketing, from supermarkets, hypermarkets, superstores and megastores or gigamarts on the one hand, and more genteel emporia, “modern large foodstores”, and Bowlby’s favourite “self-service combination store”. Hyperbolic supply and consumption, demand and production lead to inevitable magnification of waste through the same monoculture/monist desire paradigm, something that Bowlby demonstrates through the corresponding solipsism in interior design and architecture, in the very experience of personal space, of the space for family and individual living: the sameness of products defines not shared, but to an extent carbon-copied lives. Thorstein Veblen’s theory of “conspicuous consumption” is Bowlby’s prism in this case for compulsory and compulsive buying, escalating to a literally consumptive crisis…

Bowlby’s short, yet perfectly proportioned sections on the multitude of shop species are a thrill and a delight, with her entry on shopkeeping revealing how running a shop is more than a role-playing exercise. It requires both guts and gusto (something invariably lost in the modern, more corpulent versions of shopping spaces), as well as knowledge and know-how. There were manuals and exams on the art and craft of standing behind a counter, one such exam delivered by the Institute of Certificated Grocers, and consisting of three graduated papers on such vital subjects as “TEAS, SUGARS” and the intriguingly “EVAPORATED FRUIT”. Shopkeeping presupposed a sense of lineage, from the Middle Ages to the present, not only through membership of a trade guild, but also and especially in terms of belonging to a distinct, even if often hieratic community. Another fine cameo is the account of Great Patriotic Sales, Jumble Sales and Charity Bazaars, under the rubric of shopping for goods on behalf of good causes. Think Gregory Peck in Mark Twain’s The Million Pound Note, Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway, or Eliot’s The Mill on the Floss…

Back to the Shops is as much about resuming life after two years of social and communal abstinence, as it is about reflecting on what it means to exist as part of a larger narrative of social gestures, rites, practices, stories. It is a shrewd study of material culture from a comparative and diachronic perspective, as well as an opportunity for indulging in textual and meta-textual readings, in contextual analysis, or very simply for browsing in books for that human experience or encounter that completes or responds to one’s own state of mind and place. Back to the Shops is certainly a move back to books and their stories, and their ability to inspire us to trade places and perceptions, back to encounters with things and words, cultures and practices of living and belonging. Yet that backward thrust also contains a forward momentum that may perhaps yet redeem us. A hint that the second-hand may sometimes have more inherent value than the brand new; and conversely, that the lengthier process of shopping might be more meaningful than the quick, expedient and instantly gratifying act of “buying now”. Whatever your method of choice as to the acquisition of things, Back to the Shops will invite you to reflect creatively and certainly proactively as regards our relationship with thingness itself, the balance between possession and interchange, purchase and encounter. It is a fine journey into history, a resonant jaunt towards what we may well want to visit in the uncertain after…

Rachel Bowlby teaches courses on the history and theory of consumer culture at University College London, where she is Professor of Comparative Literature. Her previous books include Just Looking (on department stores), Shopping with Freud and Carried Away (on supermarkets). Back to the Shops is published by Oxford University Press.

Rachel Bowlby teaches courses on the history and theory of consumer culture at University College London, where she is Professor of Comparative Literature. Her previous books include Just Looking (on department stores), Shopping with Freud and Carried Away (on supermarkets). Back to the Shops is published by Oxford University Press.

Read more

@OxUniPress

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.

bookanista.com/author/mika/