David Gates: Mixed emotions

by Mark Reynolds

“A sizzler of a novel, a whirlwind.” Joseph Heller

David Gates’ smart, scary and intoxicatingly funny novel Jernigan, about the destructive downward spiral of a restless, alcoholic recent widower, received ecstatic reviews when first published in 1991, but since fell on hard times in the UK. Serpent’s Tail has now reissued Jernigan alongside Gates’ first new book in sixteen years, the story collection A Hand Reached Down to Guide Me. I caught up with him in the middle of a whirlwind UK tour to raise a glass to old friends and new connections.

MR: So how does it feel to be back on the road with Jernigan?

DG: I hardly remember anything about Jernigan. I read Stuart Evers’ introduction to this edition, and there are just things I’d totally forgotten about. I don’t know any writer who sits and reads his stuff again, so my memories of it are pretty faint. I’m starting to remember things from it, but it’s remote.

So where did he spring from all that time ago?

Fully formed from the head of Zeus! Where did he spring from? Well, I can tell you about his name. I worked at Newsweek for 29 years, and when I first worked there I had a friend there who had a friend named John Jernigan, he was always talking about him, and I found it such a fascinating name. I forget the names of the poetic feet, but I think it’s a dactyl. Anyway I just liked the kind of bumpy sound of it, and that was the name I hit on. I actually did a reading, I believe in Philadelphia, where John Jernigan showed up, and it was quite an embarrassing and strange moment. The other thing about the name that I found out only after the book was in galleys, there’s a thing that runs through the book about Jernigan’s Irish ancestry, but apparently it’s not an Irish name. It sounded to me like Callaghan or Monaghan, but apparently it’s some kind of Old Breton name meaning ‘iron man’. I had no idea. I freaked out and called my editor and said, “What are we going to do about this terrible problem?” He rightly perceived that it wasn’t really much of a problem, but it didn’t even occur to me to check that.

And do you think we may have heard the last of him?

You know, other people have asked me that in the last couple of days. I think so. Some writers have been successful in bringing back a character – like Updike with Rabbit Angstrom or Richard Ford with Frank Bascombe. On the other hand, no one has ever rated Mark Twain’s Tom Sawyer, Detective. So I think it’s a dicey thing to do, and I think you’re maybe in danger of claiming something for your character that he can’t sustain. I feel that he’s contained within that book, and I feel that about most of my characters, that they exist for the purposes of the thing that they’re in, and don’t really go outside the boundaries of it. It’s not impossible, and certainly I’ve thought of it, and now that I’m going on record about this, I’ll probably change my mind about it, but right now I don’t plan to.

I think he’s around 40 in this book. Let’s say he’s 40 in ’91, 50 in 2001, 60 in 2011, so… surprise, surprise, he’d be my age. Imagine that. Is he even alive?”

I was reading the book for the first time and, perhaps because it is so firmly set in the period when it was first published, I did start to think about fast-forwarding to how he might cope with today’s technology and communications.

Yeah, he would be old. I think he’s around 40 in this book. Let’s say he’s 40 in ’91, 50 in 2001, 60 in 2011, so… surprise, surprise, he’d be my age. Imagine that. Is he even alive? I don’t know. I don’t really care about these people after I’m done with them. I’m very involved with them at the time I’m writing about them, but I’m not someone who wonders what happens after the book’s published. And I don’t generally wonder that about characters from other people’s fiction.

Has there ever been a sniff of a film adaptation?

Several. Someone has the rights to it right now. There was one screenwriter who kept optioning it for several years – for not much money. Someone is looking at it now. I let him have the rights for nothing, and if he can make something of it, fine. It would be interesting, but it’s not something I really count on that much.

And you wouldn’t get involved in any screenplay?

I wouldn’t know how to do it. I love movies, but I think people who are really good at it are really good at it, and I don’t want to try and learn a new skill. Most of the movies I like are old movies. There are very few new movies I like; very few movies I see, and I think there’s maybe some new aesthetic and if I were to write a screenplay it would be like a 1930s movie or something.

This book disappeared from UK bookshops for a long spell. What’s the book’s history in the States?

It’s still in print. It came out in hardcover originally, went into paperback, and it’s still in print.

Jernigan has been compared with other rediscovered classics like Revolutionary Road and Stoner…

I’ve never read Revolutionary Road. I began it, and thought it was fun, but it began to make me a little nervous and I never finished it. Stoner I recently bought but I haven’t read it yet. Another comparison that’s made is with A Fan’s Notes by Frederick Exley, which I think I did read before writing Jernigan but had kind of forgotten about, then I re-read it and understood why the comparisons were made.

Which authors particularly influenced you and inspired you to write?

Well Samuel Beckett certainly is the most important for me. My ex-wife Anne Beattie too. She was the first writer I ever knew, naively enough, who was writing fiction out of the kind of lives that I knew. For some reason it didn’t occur to me that that’s what everybody has always done. You know, because I was a literature student, and I always thought literature was literature… but yeah, that was amazing to see that. Jane Austen was very, very important to me, John Cheever became quite important.

And Raymond Carver?

Yeah, that comparison is made a lot, and it’s flattering to me because I love his work. I’m not sure that mine is really that similar. Maybe the drinking, but stylistically I think he’s a lot plainer than I am, and my people are very, very different people from his. His are people who are generally not that articulate, that sophisticated. Mine are overly articulate and overly sophisticated. But yeah, he’s certainly someone I admire, he’s one of the people that I teach my students over and over.

What are the first tips you give your writing students?

One tip I give them is that every character in a novel or short story, or indeed a play or movie, thinks that he or she is the protagonist. And that seems to help people in thinking about their minor characters. Beginning writers are usually good with their protagonist, because their protagonist is often like them, but less strong with the so-called secondary characters. And if they can think that this person has a bigger life, that each of those characters thinks it’s his or her story, then it helps them make those characters more convincing, rather than secondary conduits for the narrative. Other than that, I don’t really have a lot of advice for them, except the small stuff everybody knows about like don’t use too many adverbs – like one is too many; don’t have a synonym for ‘said’ – don’t have your characters retorting or averring or, best of all, ejaculating. If you’ve got a scene happening, don’t interrupt it to tell the reader how to respond. But these are kind of basics. I just feel they should do what they feel like doing, try to let their emotions lead them.

Do you steer them towards reading writers and genres they haven’t encountered before?

Yes I do, or I steer them to re-read stuff they have encountered, to read it again and again to see why they admire it. I tend to re-read much more than I read. Right now I’m re-re-re-re-re-reading Bleak House. I’ve usually got a Dickens novel that I’m re-reading. I re-read a lot of things in order to teach them.

There’s a lot of music, in the novel in particular.

A lot of music; maybe too much. I try to keep the music under control, but not with any success. One of my favourite things about Jernigan, and I’m still proud of this, is that I made him not a musician. His son plays guitar, and there’s a very naïve description of him ‘tapping’, but Jernigan doesn’t know the word tapping, so he describes it in an awkward way. It was kind of fun for me to make him someone who couldn’t play an instrument.

What do you play?

Mostly guitar, I can play some pedal steel guitar. I play in a band with James Wood, who’s a marvellous drummer.

If Jernigan has a soundtrack it would be the songs of Webb Pierce. What made you land on his particular brand of cheerfully presented misery?

I love Webb Pierce. He’s a very odd-looking character. He’s famous for having had a guitar-shaped swimming pool, and also for his very fancy Western costumes. Good singer I think, great singer. The way he comes into it is Martha’s father was a Webb Pierce-like singer. I did meet someone in Nashville whose father was a country singer, so I think that situation was a little bit similar – it’s very remote…

And if you look up the songs that are referenced, they really are tales of misery.

Of course that’s true, but that’s country music. And drinking songs too. ‘There Stands the Glass’ is a great drinking song.

“Gates is like John Updike without God.” Newsday

Similarly, the title story of the collection is very rooted in the Stanley Brothers. What’s their legacy on the American music scene? Their music, and Ralph Stanley’s solo work have had a revival since O Brother, Where Art Thou?

Yeah, I think that was very important in getting him some attention. I wrote a profile of Ralph Stanley in The New Yorker, which came out around the time of O Brother, Where Art Thou? He’s become something of a touchstone and I just love his music, I’ve loved it ever since I was in high school. As in the story, you’ll be sitting around with people and they’ll argue about who gets to sing Ralph Stanley’s part.

In Jernigan, It’s a Wonderful Life is a background motif in the book, but unlike James Stewart’s George Bailey, there’s no angelic redemption for Jernigan. Should we ever expect a happy ending?

From me, or from someone else?

In general. Why has it become a tradition in Hollywood in particular to have an upbeat ending?

I blame it all on Shakespeare; those damned comedies of his! It’s a genre like any other. I mean, you can continue any of these stories to the point at which it gets grim, you could write Pride and Prejudice past Elizabeth’s marrying Darcy and then dying in childbirth. You know, it’s the genre that determines what’s going to happen; if it’s a comedy, that’s what has to happen. There is a conceit that Romeo and Juliet is a comedy. If he doesn’t drink the poison, they could go off and have a happy life. The last story in A Hand Reached Down to Guide Me has… I guess you’d call it a happy ending, it’s not an unhappy ending. I’m not sure if the ending of Jernigan is unhappy or happy. It had to end there, but it’s not the end of the story, it’s only the end of my story of him. He doesn’t put a gun to his head.

No, I guess it ends on a moment of self-realisation that could go either way.

Exactly.

There’s a battle in your work between intellect and emotion, is this something you’ve managed to crack in your personal life?

I don’t know about in my personal life, it’s a day-by-day business. Would you say my characters live more by their emotions or more by their intellect?

I’d say they’re pulled in different directions by both.

That might be, yeah. Although they’re very emotional about intellectual matters. And also tend to intellectualise emotional matters, and this will make them sort through all the implications of their feelings about each other, and their feelings about their feelings about their feelings about each other.

It often feels uncomfortable to me when a writer moves outside of the territory that he or she knows. Dickens writing the American chapters in Martin Chuzzlewit, they’re terrible, just awful.”

The landscape of New England is a dominant feature, right through the collection and in the novel. What does that countryside mean to you, and how does it feel to give it up for Montana?

It’s the only countryside I know well, so of course I would make use of it. And the weather obsesses me. It’s beautiful and sometimes desolate. And also in a way I suppose I’m consciously being regionalist about it. It often feels uncomfortable to me when a writer moves outside of the territory that he or she knows. Dickens writing the American chapters in Martin Chuzzlewit, they’re terrible, just awful. Or later on in his journals about Switzerland or Venice or wherever he is. Or John Cheever setting stories in Italy, or Russell Banks moving all of a sudden from upstate New York to Jamaica. It seldom works for me. It feels so often as if someone has been on a vacation somewhere and decided to write about it. It’s as if Dickens felt he had to use it, and he’s just more comfortable in London.

Should we blame Shakespeare again?

Oh yeah, we can blame Shakespeare for everything. I’m not sure Shakespeare knew much more about Venice than Dickens did. It’s always ‘Venice’ or ‘Bohemia’ in very heavy quotation marks. I thought I’d stick with the territory, the landscape, the ways of life that I knew well. I’m not tempted to write about Montana. I’m starting my fifth year there, and I just don’t feel I know it well enough. I love being there, I love working out there, but I’m not taking it into my heart the way I take New England into my heart. It’s what you’re used to. And the New England landscape just has emotional significance for me that other places won’t have, even places much more magnificent.

In the collection, is Banishment a short story that grew, a novel that shrank, or was it always going to be something in between?

It was always meant to be a novella.

And what determined that?

Well, my editor asked for either two stories or a novella, and I thought it would be easier to start one piece than two, and as soon as I got started I saw that it could indeed be a novella. I’d never written one before – no, I guess I had. The first thing I wrote, well before Jernigan, that never was published and never should have been published, was probably about the length of Banishment. I thought of it as a novel, but I guess back then I didn’t know what a novel was. Since then it’s the only thing I’ve written at that length. I’m trying to get started on another novel now, and I think it will be a short one, maybe a couple of hundred pages, and I’ll see how that length feels to me. But this length, it’s about 100 pages in the book, that seems a very comfortable length to me. It doesn’t go on forever, and it’s a lot fuller than a short story.

Could it be that the novel you’re planning may actually end up at a similar length?

I don’t know. I have two beginnings, and they seem to be beginnings of different novels, and neither of them is very satisfactory, so I’m going to have to start again. Sure, if I’m lucky enough to end up with 300 pages and it needs to come down to 100, I’ll do that.

How long has novel writing taken you in the past?

A pretty long time. Jernigan took about four years, I think, Preston Falls was about seven, but I had trouble writing it. I wrote a first draft that was half as long again as the published novel, and it was terrible. For example, the main character’s getting a divorce and in the original version he had an affair with someone, and he’d never have done that, he’s way too disengaged to have done that. Also the original version was two first-person monologues, which I decided wasn’t working so I changed it to third person. I finally got it into fairly good shape, but it was much harder to write than Jernigan.

It’s surprising, after Jernigan, to think of your abandoning the first person, because the reader is totally inside the character’s head in that novel. But you found you had to?

I did, yeah, for a couple of reasons. One, it just seems awkward to me to have two first-person narrators. If a scene happens between them, who gets to narrate it? If you’re in third person, those transitions become so much easier. Also the first draft was in the past tense, but the novel’s in third-person present, so that was another big change that I had to make.

Can we expect the re-release of Preston Falls anytime soon?

I’d be very happy if that happened.

And is there a timetable for finishing the next one?

Oh yeah, I very rashly promised my agent and my editor that I would give them something next summer. I don’t know how that’s even possible. But I wrote the novella fairly quickly, and the last story I wrote in the collection, ‘Locals’, which is a longish story, came quickly. I did that in a month, and ten days of that month I was busy teaching. Since I was a journalist for so many years, I never missed a deadline. All the time I was at Newsweek I only knew of one writer who just had a meltdown and couldn’t hit a deadline. And this on a magazine with thirty, maybe forty writers, that’s amazing. So I was thinking that if I gave myself this sort of artificial deadline, maybe the old habits would kick in.

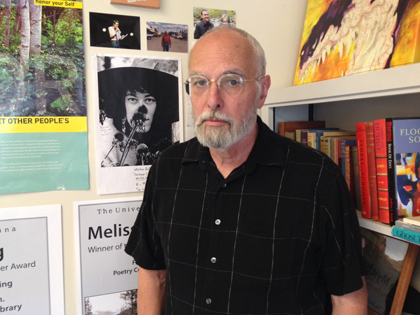

David Gates lives in Missoula, Montana, and Granville, New York. He teaches at the University of Montana and in the Bennington Writing Seminars. As an editor at Newsweek, he specialised in music and books. He is the author of the novels Jernigan (1991) and Preston Falls (1998), and the story collections The Wonders of the Invisible World (1999) and A Hand Reached Down to Guide Me (2015). Jernigan was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and National Book Critics Circle Award. Gates’ stories have appeared in the New Yorker, Rolling Stone, Esquire, Paris Review and Granta. A new edition of Jernigan and A Hand Reached Down to Guide Me are published by Serpent’s Tail in paperback and eBook. Read more.

David Gates lives in Missoula, Montana, and Granville, New York. He teaches at the University of Montana and in the Bennington Writing Seminars. As an editor at Newsweek, he specialised in music and books. He is the author of the novels Jernigan (1991) and Preston Falls (1998), and the story collections The Wonders of the Invisible World (1999) and A Hand Reached Down to Guide Me (2015). Jernigan was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and National Book Critics Circle Award. Gates’ stories have appeared in the New Yorker, Rolling Stone, Esquire, Paris Review and Granta. A new edition of Jernigan and A Hand Reached Down to Guide Me are published by Serpent’s Tail in paperback and eBook. Read more.

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.

@bookanista

Brett Marie discusses Jernigan and the abiding allure of ‘loser lit’.