Elena Lappin: Secrets and lives

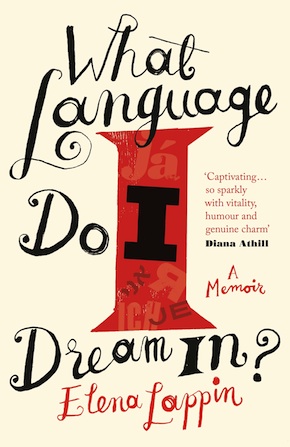

by Lucy ScholesIn Elena Lappin’s novel The Nose, her protagonist Natasha Kaplan, a young New Yorker in London editing an Anglo-Jewish magazine, discovers more than she’s bargained for when in the course of her new job she ends up uncovering secrets about her own family’s past. “I thought I had invented and imagined it all,” writes Lappin towards the beginning of her enthralling memoir What Language Do I Dream In? “But perhaps I was writing about what I did not yet understand, but had lived with all my life.”

In 2002 – a year after The Nose was published – Lappin was having dinner with her husband and their three children in their north London home when the telephone rang. The caller – male, clearly agitated, and most comfortable speaking Russian – informed her that the man she’d known her entire life as her father was not, in fact, a blood relation. Her biological father was a Jewish American now living in New York, who had met Lappin’s mother in Moscow in the 1950s. Lappin’s mother married the man Lappin had grown up believing was her father when she was a toddler, and they kept the true story of her origins a secret from the daughter they raised together for the next forty-seven years.

As well as telling what turns out to be a fascinating story of her origins, and in the process, of how families are made, Lappin’s memoir is also a moving and insightful meditation on identity – individual, familial and national – through the prism of various languages.

“Perhaps my life could be described as five languages in search of an author,” Lappin wittily muses towards the end of her story. Born in Moscow in 1955, Lappin was three when she and her mother left Russia to join her father-to-be in Prague. The family – now with her young brother Maxim in tow – then moved to Hamburg in 1970. Although only a border hop in terms of physical distance, during this period Soviet-controlled Czechoslovakia and West Germany were worlds apart, the journey between them a one-way trip: “You cancelled your old life and lived with the consequences.” Five years later, as a young woman spreading her wings, Lappin moved again, this time to Tel Aviv, a home away from home for many a Soviet Jew during the ’70s. This was where she met her husband – a Canadian whose family were part of the East European Jewish diaspora who emigrated West – and where the couple made their home together for the next five years. After spells in Ottawa, Haifa and the suburbs of Westchester, New York, the early ’90s brought what turned out to be a permanent relocation to London. England became Lappin and her family’s home (during the course of their wanderings they had welcomed three children into their midst), and with it, and “after a journey through four others” – Russian, Czech, German and Hebrew – English the language in which she eventually decided to write.

I knew immediately: that’s how it’s done… If I could find my way into this lightness, my dream of becoming a writer could still be saved.”

Lappin always wanted to be a writer, but she only really discovered her voice in this language that was four times removed from her mother tongue. “I have always found the books I needed in my life,” she writes, “at just the right time and seemingly by accident, without actually looking for them, at least not consciously.” Of all the titles to cross her path, the one that made her want to write in English was an old 1950s paperback that caught her eye in a second-hand bookshop when she was in London on her honeymoon in 1977: My Face for the World to See, by Alfred Hayes. From the very first paragraph – before she knew the story, or was even able to fully understand each and every word with what was her then “literary-beginner’s English” – the book still gave her an immediate thrill. “I knew immediately: that’s how it’s done,” and she wanted to do it too: “If I could find my way into this lightness, my dream of becoming a writer could still be saved.”

Lappin always wanted to be a writer, but she only really discovered her voice in this language that was four times removed from her mother tongue. “I have always found the books I needed in my life,” she writes, “at just the right time and seemingly by accident, without actually looking for them, at least not consciously.” Of all the titles to cross her path, the one that made her want to write in English was an old 1950s paperback that caught her eye in a second-hand bookshop when she was in London on her honeymoon in 1977: My Face for the World to See, by Alfred Hayes. From the very first paragraph – before she knew the story, or was even able to fully understand each and every word with what was her then “literary-beginner’s English” – the book still gave her an immediate thrill. “I knew immediately: that’s how it’s done,” and she wanted to do it too: “If I could find my way into this lightness, my dream of becoming a writer could still be saved.”

Many writers would give their eyeteeth for a tale of such writerly origins. It sounds like something one would encounter in the pages of a novel, not to mention a broader life story as interesting as hers – one in which after nearly half a century, a writer who actively chose the English language realises its something that’s been enfolded deep down in her DNA all along – so it came as something of a surprise to hear Lappin describe herself as a “reluctant memoirist.” This is the first thing I ask her about when we meet.

“Although my life is, I suppose, kind of unusual,” she readily admits. “I never felt that for me personally it would be interesting to write about it.”

She’s not exactly an avid memoir reader either; only able to recall a handful she’s really enjoyed. Mary Karr’s The Liars’ Club and Nabokov’s Speak, Memory, for example, “because the writer’s going in an almost fictional-style search for the narrative of their lives.”

These two elements, however, clearly came together in what transpired following that momentous phone call. A new story about her life ready and waiting to be uncovered – as yet unknown and thus fresh enough to pique Lappin’s own interest – and the pursuit of it providing her with precisely the kind of near-fictional search for a narrative she admired in Karr or Nabokov’s works.

I was confronted with this mystery: How did I actually choose English as my language? And how does my kind of English, which is obviously not that of a native speaker, contain my other languages?”

Around the same time, taking part in a translation summer school at the University of East Anglia, as an author whose work was being translated by the students, set her thinking about her own linguistic heritage.

“Suddenly I was confronted with this mystery: How did I actually choose English as my language? And how does that English – my kind of English, which is obviously not that of a native speaker – contain my other languages? What actually happens in a writer’s mind when they do this?”

Well aware that she wasn’t the first writer to adopt a language and make it her own, she was interested in the potential of being able to observe the process from within.

“I felt it was something worth writing about because it’s about being a writer, but it’s also the story of my life from a certain perspective.”

In the lightning bolt that was the revelation of her true parentage, these two investigative strands were fused together.

“In my case, the well-known saying ‘follow the money’ could be replaced with ‘follow the languages’, as each led to another world. Without my presence their stories were literally all over the place,” she writes, referring to her parents and grandparents, “without an arc to hold them together, and without an interpreter to explain their meaning. This, it turned out, was my role.”

“Discovering my biological father was not who I thought he was, initially I thought This is a story I possibly need to write about once I’ve figured it out,” Lappin tells me, “but it wasn’t until I started really researching it that I realised how far it went in terms of historical, political and family developments, and how it really captured the story of 20th-century history on both sides of the political divide.”

“Discovering my biological father was not who I thought he was, initially I thought This is a story I possibly need to write about once I’ve figured it out,” Lappin tells me, “but it wasn’t until I started really researching it that I realised how far it went in terms of historical, political and family developments, and how it really captured the story of 20th-century history on both sides of the political divide.”

As such, the two elements combined with a keen sense of urgency.

“I felt that until I’d dealt with this material specifically in the form and shape of a memoir, and nothing else, I couldn’t go back to any other project.”

It wasn’t an easy task though; the entire enterprise taking about eight years from start to finish. The language element under discussion was fairly straightforward; it was the personal part that she struggled with. Initially, as one can imagine, she had to tread carefully while unearthing secrets her parents had specifically kept buried for so many years. She grew up in a house always full of conversation; her family’s wasn’t a home where people held their tongues for the sake of politeness. Discussion, even argument was encouraged, but here was something – perhaps the only thing – her parents had never breathed a word about. Now, for the first time, she had to contend with the possibility of hurting the feelings of people closest to her, not to mention dealing with her own emotions of hurt, and even anger at not having been told the truth. Then, as she progressed with her research, a sort of inverse delay mechanism kicked into action as her investigations took her down one fascinating rabbit hole after another.

Lappin is no stranger to writing what she describes as literary investigative journalism. Her excellent essay ‘The Man with Two Heads’, published in Granta in 1999, explored the story of Holocaust imposter Binjamin Wilkomirski, author of Fragments: Memories of a Wartime Childhood. Met with international critical acclaim on publication, the book’s veracity was later debunked by a journalist who put forward evidence that Wilkomirski’s entire account was a product of his imagination. What attracted Lappin to this particular story, she explains, was a fascination with uncovering the truth.

“There was a lie, a question mark – the main thing for me was to have all the facts available before I could even decide.”

When it came to writing her own memoir, she used the same methodology that had served her so well previously.

“I approached my own personal family mystery in exactly the same way,” she says, explaining that writing about oneself is exactly the same as writing about a complete stranger: “So suddenly your home and your family archive is just that: an archive. Those photographs, those albums, those stories – they’re all just material.”

“I love spending time in archives and in libraries and on the internet discovering more and more clues, and this led me to such interesting stories, so many that I couldn’t even begin to mention them all in my book – espionage in Shanghai in the ’30s, for example – I had to stop myself, I had to say to myself, This is great stuff, but it’s not your story. One of the most important things I learned in the process of writing the book was, Remember what your story is, and stick to it. You can’t get carried away because then the book will never be born.”

As she knew from researching Wilkomirski’s story – despite having been ‘found out’, he never admitted to any fictional construction, apparently genuinely believing that the story he’d created for himself was the true account of his origins – memoir is all too easily constructed on shifting sands.

“In writing, there is fiction and non-fiction,” she writes in ‘The Man with Two Heads’. “These seem clear divisions, but as any writer knows the boundary can be blurred, and nowhere more so than in this literary form ‘the memoir’. Trying to evoke the past the memoirist needs to recreate it, and in doing so he may be tempted to invent – a detail here and there, a scene, a piece of dialogue.”

A conscientious memoirist is one engaged in constant curtailment. On the one hand, it’s imperative to not let your research run away from you; and on the other, one mustn’t let one’s characters off their leashes either. The temptation to fictionalise the lives of the people she was writing about was a strong one, Lappin explains – she saw entire avenues of possibility laid out in from of them, but pursuing these would have been a different project entirely.

“I could take this bit or that bit and create fascinating fictional narratives around those characters, they’re all ready for that, but because I was writing a memoir, my task was different. It was to tell the truth as much as I know it and can tell it about them, but from within, so to get to understand it – not just to see where they lived and what they did – but to actually understand it, to understand what motivated them and why they did the things they did.”

A large part of the work then was constant pruning, all of which was done under the ever supportive and discerning eyes of her editor at Virago, Lennie Goodings.

“There was an interesting sort of mistake I made when I wrote one of my earlier drafts. I felt, It’s all very complicated, it’s all over the place, it covers so many different things, so I don’t really need a chronology, I can just tell it the way I feel it. If I connect this with that and it makes sense to me, well that’s fine. Well, it wasn’t fine. I had to go back to basics and create a proper chronology – and this, by the way, was Lennie’s big insight as well – once I had the chronology I could then sometimes go off and talk about things that weren’t in that particular domain because the reader always knew what it was linked to, but the chronology was something that I almost had to force myself into, but now I’m so glad I did because once I made that decision the whole thing came together.”

For me, one of the most intriguing elements of Lappin’s story is a working life that replicates her linguistic one in that it’s undergone a variety of permutations. Over the years she’s been a literary journalist, the editor of a magazine, a novelist, a short story writer, a literary scout, and is currently the editor of Pushkin Press’s much admired ONE imprint as well as a memoirist.

For me, one of the most intriguing elements of Lappin’s story is a working life that replicates her linguistic one in that it’s undergone a variety of permutations. Over the years she’s been a literary journalist, the editor of a magazine, a novelist, a short story writer, a literary scout, and is currently the editor of Pushkin Press’s much admired ONE imprint as well as a memoirist.

“My career – if you want to call it that –” she begins.

I interrupt. “You wouldn’t? Why not?”

“No, I wouldn’t,” she tells me firmly, “because in a career someone starts in a certain place and then they progress and get a promotion and go up and up as far as they can get, and it’s all very linear and solid. My ‘career’ – not as a writer now, but in publishing – I’d call it quite dynamic. I was always guided by my own personal interests: if I felt like editing a magazine then that’s what I did for a few years; if I felt like being a scout, then I did that; if I felt like editing books suddenly there was an opportunity to do that. I work that way because that’s the way my mind works. I have to be passionately interested in what I’m doing. I found it fascinating to be a scout, for example – to play literary match-making between publishers and books, across different languages and thinking in terms of different cultures and how a book could travel from one language to another by being matched up with the right publisher in a different country.”

In the memoir she describes the “narrative pattern” of her life as “more like a series of concentric circles than a linear narrative.” The same description could well be applied to her working life, could it not?

“What is very true is that I’m never just in one thing. I’m always aware of a much wider context, with everything. I also do this in my work as editor; I have a sense of a book connecting with the world in a way that gives it a lot of depth. I never want a book to be in a static place, I want people to really respond to it in a very alive way. I want it to be a live thing.”

Which came first, I wonder? Has the way she’s lived her life and constructed her identity had a knock-on effect on her work, or did it begin with a search for the bigger picture – a pursuit that fuelled her own wanderings between different countries and cultures?

“The truth is that I’ve been like this ever since I was a kid. Before I even knew anything that may have influenced me, I was kind of hyperactive in the way of always starting magazines. Every few years, no matter where I was, I always had to start a magazine: this school, that school; this language, that language. For me, this was a way of having a place to write, to work with friends who could do the same, to have a lot of fun, and to create a world which has a kind of life of it’s own. I fell in love with editing magazines and writing magazines literally from primary school. So when I got to actually edit a real magazine as an adult [Lappin was the editor of Jewish Quarterly in the ’90s] that was the ultimate plaything.

“But basically that’s just my nature. Since childhood I’ve always wanted to do things that were fun, and that were not just for me. That’s why I don’t like the idea of talking about it as a career, I always wanted to do things that would be fun for a lot of people, to be engaged in discussion, and to be passionate about whatever I was doing – I think that’s a very Central European, a very Prague thing. I think I bring it with me. Obviously I was a child when I lived there so I wasn’t part of that scene, but I could see it happening when I was growing up as a teenager and it was present in everything I was reading; I could see myself in it.”

What I’ve been through was an absolute piece of cake compared to what my grandparents’ or my parents’ generation had to live through, and they all did that with joy.”

Given just how much loss it contains, one would be forgiven for assuming Lappin’s memoir might be something of a melancholic or nostalgic affair. In actual fact though, it’s strikingly joyful.

“I think that has to do with the way I grew up. To this day – and they’re in their eighties now – my parents’ home is a hilarious place, always full of people and arguments. My mother told me recently she’d hosted a dinner – which she’d cooked – for twenty people. She was pleased for actually having done it, but she was even more proud of herself for starting an argument with one of the guests about a political issue, provoking him into voicing his views, views she didn’t agree with. I guess it comes from being brought up like that – it’s very real. It’s about getting together and talking. I just love that; I think nowadays we’re all a bit too cautious about expressing our views.

“But aside from that, as you can also tell from the book, what I’ve been through has perhaps not been that easy, but it was an absolute piece of cake compared to what my grandparents or my parents had to live through, and they – not only them but also their relatives and friends, people of that generation – all did that with joy. That’s how they lived and what they passed onto us: living life with joy, enjoying every moment, and when bad things happened you just picked yourself up and kept on going.”

Lappin’s own conception is perhaps the best example of this attitude (helped along, no doubt, by the fact that being unmarried and pregnant was not a problem in the Soviet Union in the ’50s). As she explains in the memoir, her mother’s unplanned pregnancy “was something everyone just accepted: it just happened, the timing was neither good or bad – it just was.”

There’s a difference though between this outlook of “taking things as they come, getting on with them whatever fate might serve up, planned or unplanned, wanted or not,” and the sort of passivity so often associated with the émigré experience, the latter sitting somewhat uncomfortably with Lappin.

“Émigrés like to see themselves as victims of circumstance,” she writes, “of higher forces that deprive them of the chance to live their lives as originally planned – had that war, revolution, financial disaster or nasty neighbour not prevented them from staying in the country of their birth. As a multiple émigré myself, I have come to resent this sentimental, self-pitying, teary-eyed view of what is, of course, a genuine loss.”

In part due to her positive outlook, and in part down to the skilful way in which she weaves an account of the émigré experience through her story, she does need to remind her readers of the full extent of this loss. It’s something that joy and humour can go a long way to obscuring, but will ultimately never entirely eclipse. Reprinting an oft quoted passage on the subject from her short story collection Foreign Brides, she explains that although the book “was meant to be a (mostly humorous) take on foreignness and marriage,” many of her critics successfully identified “the real core of it as the rootlessness of exile: an abyss rather than an amusing gap in one’s life.”

“I had a conversation very recently with a friend of mine,” she tells me, when I press her on the subject. “She emigrated from Prague before me and we reconnected recently. We talked about emigration and what it did to us. I said that it was a wound and something you never really lose, overcome or forget, and she said something she’d never told me before, that the pain of emigration was as deep as the pain of losing her father when she was young – they were the same in her mind – and as a consequence she could only deal with the emigration by never moving again. I said, ‘Yes, that’s kind of what I’m writing about,’ and she was surprised: ‘But you’re always laughing, you’re always moving, you’re always having fun?’ This was interesting to me, that she thought I’d responded in a different way, but really we both felt exactly the same way, it’s just that my character is different to hers. I think there’s a degree of denial that you simply have to have in order to move on, like with any loss. And although it’s always been my choice to deal with it in the best possible way, and to have fun where possible, it’s still a very real loss.”

Significantly though, the image the book ends with is that of Lappin walking her dog in the medieval forest near her north London home, the roots beneath her feet reminding her of the Prague of her childhood, and the bludný kořen, “a mythical tree root that had the power to make you wander for ever, never finding your way back.”

“I must have stepped over it many, many times,” Lappin writes. True. But interestingly the roots I’m most aware of as I read these closing lines are the new ones she’s planted and is now tethered by here in her adopted homeland. What Language Do I Dream In? is a story of finding and making a home as much as it’s about leaving and losing one.

Elena Lappin is a writer and editor. Born in Moscow, she grew up in Prague and Hamburg, and has lived in Israel, Canada, the United States and – longer than anywhere else – in London. She is the author of Foreign Brides and The Nose, and has contributed to publications including Granta, Prospect, the Guardian and the New York Times Book Review. She is the editor of ONE, an imprint of Pushkin Press. What Language Do I Dream In? is published by Virago Press in hardback and eBook. Read more.

Elena Lappin is a writer and editor. Born in Moscow, she grew up in Prague and Hamburg, and has lived in Israel, Canada, the United States and – longer than anywhere else – in London. She is the author of Foreign Brides and The Nose, and has contributed to publications including Granta, Prospect, the Guardian and the New York Times Book Review. She is the editor of ONE, an imprint of Pushkin Press. What Language Do I Dream In? is published by Virago Press in hardback and eBook. Read more.

@elenalappin

Author portrait © Jerry Bauer

Additional images courtesy Elena Lappin

Lucy Scholes is a contributing editor to Bookanista and a literary critic and book reviewer for publications including the Daily Beast, the Independent, the Observer, BBC Culture and the TLS. She also teaches courses at Tate Modern, Tate Britain, the BFI and Waterstones Piccadilly. @LucyScholes