Elsa Drucaroff, Rodolfo Walsh and Argentina

by Quentin BatesThe years of the military Junta cast a very long shadow in Argentina, and it’s thoroughly poignant that Rodolfo Walsh’s Last Case appears in English just as the country has taken a swerve in a desperate new direction. I had never heard of Rodolfo Walsh. That was put right by Slava Faybysh when he brought his translation of Elsa Drucaroff’s electrifying thriller to Corylus Books, the nano-publisher of translated fiction I’m involved with. Slava’s enthusiasm for the book was infectious, and my interest was sparked – both in the book itself that he was so keen to translate from Spanish – and as soon as I figured out he had been a real person, in the enigmatic Walsh himself.

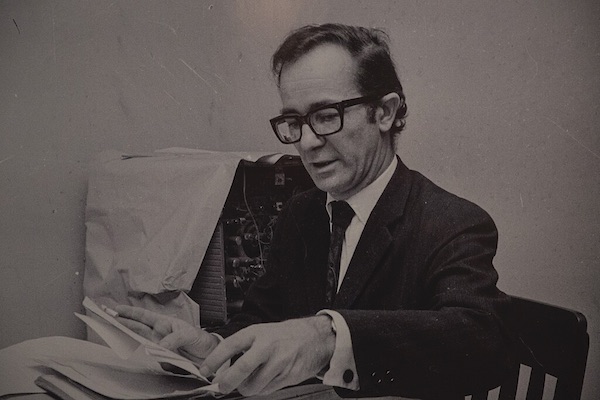

As a journalist and a writer, Rodolfo Walsh is an interesting figure, not least for the claim made on his behalf that he was the forerunner of the genre we know today as True Crime. This was years ahead of anyone else, with his 1957 account of the José León Suárez massacre a year previously, when a group of suspected Peronist activists were rounded up and shot by the Buenos Aires police.

As a political figure, and the head of intelligence for the Montoneros armed resistance, he becomes a genuinely fascinating but far more shadowy figure. We’re never going to know exactly what he did, or even what became of him following the shoot-out with the military in which he’s believed to have lost his life – not long after the murder by Junta forces of his activist daughter Vicki.

I couldn’t help being curious – wanting to know more about this deeply interesting figure, his place in Argentina’s culture and politics, and especially in what it was that brought Elsa Drucaroff to write about him, in a narrative that is both deeply touching and jarringly brutal. I fired off some questions to her last November, as Argentina was in the midst of a general election that would see right-wing populist Javier Milei sweep into power.

Quentin: Could you tell me a little about your own background as a writer?

I always knew I wanted to be a writer, and began writing at a very early age. I kept a private diary from childhood until a few years ago. I’ve written since forever, but I started publishing books in my mid-thirties. Everything I do revolves around literature. I taught language, literature and Latin at a secondary school, and for decades I’ve worked as a lecturer and researcher specialising in Argentine literature and literary theory at the University of Buenos Aires. I write novels, short stories and essays on theory and criticism. I also coordinate literary workshops, and I gave the first ever creative writing graduate seminar in a Humanities Department in my country (it was in 2015 at the University of Buenos Aires).

I love building difficult, complex personalities and moving them through ethical and emotional dilemmas in which things are not so clear or easy to judge.”

I’ve written four novels set during key moments of Argentine history, which are a cross between historical novels and popular genres like adventure, spy novels, thrillers and melodrama. The plots are completely fictional, with a lot of action inserted in a rigorously-constructed historical world, with my own understanding of the sociopolitical conflicts being the starting point. An understanding informed by a woman’s gaze. I love building difficult, complex personalities and moving them through ethical and emotional dilemmas in which things are not so clear or easy to judge.

When did you become aware of Rodolfo Walsh’s work, and what effect did it have on you?

Rodolfo Walsh died when I was 18. At the time I worked at a leftist cultural magazine that was well-known during the political radicalisation of 1970s Argentina. The magazine was called Crisis, and it was also influential throughout South America. The Argentine military dictatorship began in March 1976, and the magazine became defunct a few months later. At the time we were constantly receiving news of contributors and colleagues of the magazine who had disappeared or escaped the country out of the blue. A few of us Crisis workers stayed there vegetating, while getting other jobs. Either that or we concocted ways to publish, in the same magazine, things that wouldn’t offend the military. I was still in that newsroom in March 1977 – it was nearly empty – when someone came with the news that Rodolfo Walsh had died the day before at a Buenos Aires intersection. It was him, by himself, against at least fifty troops. They carted away his body but before he died, the previous day, he had circulated through underground channels a letter against the Junta. Rodolfo Walsh was famous at the time. I knew his book Operation Massacre. I had seen the movie version which was filmed before the dictatorship. I knew who he was.

And although I didn’t quite know what ANCLA was, the Clandestine News Agency that he had founded, I saw strange things around me. There were certain people who still came to the magazine offices on a certain day of the week, always meeting the same person. These things caught my eye, and many years later when I decided to write this novel, I realised that these ‘strange occurrences’ were no less than the clandestine human information chain that was put in place to give and receive information back and forth from Rodolfo Walsh, so that he could compose his famous informational cables for ANCLA, cables that were sent by mail with no return address except for a small anchor logo (ancla is the Spanish word for anchor). The Monday after Walsh died, I went to the Crisis offices, and someone came by with one of those letters. Inside the unsealed envelope was the famous Open Letter from a Writer to the Military Junta, the text that Rodolfo Walsh wrote one day before he was ambushed by the armed forces at an intersection in the Buenos Aires neighbourhood of San Cristóbal. The person who brought the envelope told us about the ambush, told us about how Rodolfo Walsh had died a few days earlier. I had that letter in my hands, that envelope. I was scared and full of admiration and the need to let everyone know what the letter said. It was a devastating review of one year of military dictatorship. I was very sad.

Twenty years later, when I was a university lecturer, I began reading through Walsh’s oeuvre, his excellent English-style police stories with his distinctive detectives, his perfectly thought-out plots in which the details fit together with clockwork precision, little gems of the police genre. I also read his other, much more experimental stories, which explored up-to-the-minute literary styles influenced by avant-garde narratives of the twentieth century. Finally I read his researched political and journalistic books written after Operation Massacre, which made use of creative techniques from the thriller genre to narrate the most rigorous reconstruction of facts. Operation Massacre was, in fact, the first True Crime book in modern literature, published nine years before Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood. There, Walsh investigated the covert, illegal executions of twelve Peronist citizens, perpetrated by police under the military government of Pedro Eugenio Aramburu in 1956. Walsh later wrote other books in which he investigated further political assassinations.

I couldn’t stop thinking about everything that happened. A girl firing against a throng of enemies. A military helicopter circling overhead. A father, also a guerrilla, alone, in hiding, receiving the news.”

In the beginning of the nineties, I decided to focus my seminars in the UBA Humanities Department and the Joaquín V. González Pedagogical College on Rodolfo Walsh’s oeuvre. One of the texts we analysed was the account he wrote about his daughter’s death, Letter to My Friends. She was a Montoneros guerrilla, like him. When I was 18, I had read the news of María Victoria Walsh’s death in the newspapers. It was one of the few tyrannical actions that the dictatorship had admitted to, cataloguing it under the legal framework of ‘armed confrontation’. When the dictatorship was over, I knew that in reality ‘confrontation’ meant massacre. Vicki Walsh and four guerrillas firing against over 150 troops with armoured cars, two small tanks and a helicopter. Rather than merely killing them, what they really wanted was to bring them down, make them disappear, and torture them for information before killing them. Vicki was very young, and she and another compañero fired back from the roof. After this incident, their bodies never appeared again.

When I read Walsh’s account of their deaths, I couldn’t stop thinking about everything that happened. A girl firing against a throng of enemies. A military helicopter circling overhead and firing its machine gun. A father, also a guerrilla, alone, in hiding, receiving the news – because I remembered reading about it in the newspaper, at a time when the media didn’t publish news of disappearances. I imagined this father who investigated political killings, and now he was faced with the killing of his own daughter. A succession of such images went through my head, and a lot of feelings. I myself had just become a mother, and I wondered about my own baby, and the baby that was Vicki, who Walsh watched grow up. Walsh’s letter mentioned that when Vicki fired her Uzi against the hundreds of troops, she laughed. He cited a witness, a conscript who took part in the operation. I said to myself that Walsh must have investigated his daughter’s death like he had investigated other deaths before, and he had managed to speak with an eyewitness. I imagined him moving clandestinely, desperate but committed to finding out the truth. I said to myself “this could be the plot of a thriller,” one in which we know the ending, but we don’t know how Walsh got there. That is where the mystery lay, and that was how Rodolfo Walsh’s Last Case was born.

Tell me about Rodolfo Walsh, in terms of what he means to Argentinians in general, and to you personally?

In Argentina, Rodolfo Walsh is considered by critics and historians of literature to be one of our greatest writers, regardless of the political positions of these critics or Walsh himself. Until very recently, I would say no more than these past two years, Walsh was also considered a hero to those who wish to take up the struggle for socialism from the sixties and seventies. And of course, others considered him to be a man who struggled for his cause with honour, but for the wrong reasons. Some criticised him for having chosen the path of violence and armed struggle to defend his ideals. But no one questioned his principles and his political ethos.

Personally, I admire Walsh as a writer and I admire his political bravery. My position on the guerrilla struggles of the seventies is complex. It can’t be resolved with an abstract condemnation of violence or with an uncritical celebration of the struggle for justice at any price. I think my position on the evolution of the Montoneros guerrilla organisation comes through in the novel. I can’t make a single judgement about it. Political violence might be a desperate recourse against an oppressive, violent state in certain contexts, and it can also be an expression of bloodthirsty madness that doesn’t represent the political forces that are struggling for justice, but a handful of armed individuals who are in it for themselves, and who are becoming decadent in political and human terms. I am convinced that Walsh was never the latter, and that moves me.

Nevertheless, I don’t like the male concept of hero, regardless of the cause, and I also wrote Rodolfo Walsh’s Last Case against this idea of Walsh as a hero. I don’t like that a hero should be infallible. I don’t like perfect people that make people think they never make mistakes, that they have no fear. I don’t like that we judge our peers without shades of grey, nuances and contradictions, because that is what makes us human: we are contradictory, hesitant, fallible.

What I love about Walsh is his ability to commit, even if he has his doubts. What drew me in about him was also seeing political documents from the time in which it was clear that he was not sure about a lot of things, he had questions. For example, I read about a heated internal debate within the Montoneros Executive Board in 1976, at a time when militants were dropping like flies at the hands of the dictatorship. Not only did Montoneros deny these disappearances, but they doubled down on violence and offensive tactics, unnecessarily exposing their members to risk of being massacred. In this context, Walsh rejected these instructions that ordered militants to go and die. He argued very intelligently for declaring a truce and putting an end to armed actions, not because he thought the military would accept such a truce – he explained that this would not happen – but because, as he wrote, word for word, Montoneros could not afford to lose its reputation as a standard-bearer of human rights. Walsh said in this document that the people that followed them (a huge number of people) had become tired, and the grassroots no longer followed Montoneros. It moved me to read this document because Walsh didn’t leave the organisation despite these harsh things he was saying and despite the fact that he wasn’t being listened to. He kept fighting and died alone, firing with his small-calibre gun against over fifty troops. It seemed to me that he thought breaking his commitment because his team was being defeated was detestable. I imagined how scared he must have been. I imagined him choosing to die like his daughter one year previously. This is the Walsh that moves me, the one that knows he is going to lose, that he will probably lose his life, the one that has already lost a daughter, the one that knows the political delirium of his organisation, and still he stays like those Borgian characters who have chosen their destiny, who are who they are with no going back. This is not heroism per se. It isn’t about the absolute certainty of good and evil. It happens because the choices we make bring us to a point at which abandoning the struggle in order to survive is more destructive than dying.

I am also moved by the father Walsh who tells his friends, in extraordinary and contained prose, how his daughter died. Behind every word of this letter is a father’s cry of pain, though it’s not explicit in Walsh’s text. In contrast, Walsh does tell us about when his daughter was a baby, and she laughed at things that surprised her. Walsh needs to understand why his daughter laughed every time she sent out a spray of machine-gun fire from her roof, in the last few minutes of her life. In this letter, we see a father, not a hero.

This is the Walsh I wrote about. This was my character’s starting point. He was considered a hero in Argentina, but my intention was to create a protagonist for my thriller who was a man that suffered, although he didn’t know how to express it, someone who felt as weak and impotent as anyone faced with such a tragedy, fighting back the only way he knew how: by investigating and by writing.

Without making Walsh into an angel, without idealising him, and without leaving the realm of fiction, the novel gives us a way to think critically about a protagonist of our history and our literature.”

But recently the figure of Rodolfo Walsh has been slandered in my country, and certain things that in my view are unquestionable have been questioned. I can’t not mention what is happening in this context. A far-right option has emerged in Argentina, and today, Sunday the 19th of November, as I write these lines, there is an election underway to determine if this far right will govern the country or if we will manage to stop it. The presidential candidate, Javier Milei, and especially the vice-presidential candidate Victoria Villarruel, are deniers of the crimes against humanity committed by the military dictatorship. They support the forces of repression that committed acts that were infinitely more heinous than any of the guerrilla attentats that occurred. They are trying to change our collective memories with open lies. Today, Walsh is a victim of these lies. A completely false accusation is being made against him, in which he is attributed with being the mastermind behind the bombing of a police dining hall. This bomb was, in fact, placed by Montoneros in July 1976. The sole fact that Walsh was chief of intelligence for Montoneros is used to claim that he thought up and coordinated this attack. It was an unquestionably bloody and harmful act, and I would add politically clumsy. But there are documents that exist in which Walsh specifically mentions and condemns it. He considers it a grave error and explains why. He warns, among other things, that Montoneros would lose its status as a standard-bearer of human rights. Some sections of these documents are cited in Rodolfo Walsh’s Last Case. I used them to build dialogue and discussion. But what was then just another source for the novel, today proves that the far right’s claims are slander.

Campaigns to demonise the victims of the genocide perpetrated by the military are on the agenda once again. One might say that at this moment in my country, the meaning of Rodolfo Walsh is being disputed, so it makes me happy that this novel exists. Without making Walsh into an angel, without idealising him, and without leaving the realm of fiction (because most of the plot is imaginary) the novel gives us a way to think critically about a protagonist of our history and our literature. We can argue about him in a million different ways, but he can never be congealed within the label of saint or demon.

How was the book received in Argentina?

The book came out in 2011, a moment of triumph in the cultural battle for memory, truth and justice with respect to the dictatorship’s crimes against humanity. It was very well received by literary critics and by young people who wanted to think about that political moment which they had not lived through themselves. It was not very well received by certain nostalgic seventies militants who were offended because they felt that the book did not portray the guerrillas as sufficiently heroic. In general, the book was read and discussed widely. Its cinematographic rhythm and its tense action were spotlighted. There was one thing that was mentioned that surprised me a little: my supposed ‘bravery’ and my ‘nerve’ to dramatise a character as ‘venerated’ as Walsh. I use quotes because these things were repeated in reviews and interviews to the point where I remember saying to one reporter, “I don’t venerate anyone.” Venerate is another word I don’t much care for. You can love people if you understand them. You can empathise (or not) with people. To venerate or to demonise means to lose all understanding and the ability to think critically.

Translated by Slava Faybysh

—

Elsa Drucaroff was born and raised in Buenos Aires. She holds a PhD in Social Sciences and is a professor of literature at the University of Buenos Aires, where she has taught for several decades. She is the author of four novels and two short story collections. She is also a prolific essayist and has published numerous articles on topics such as Argentine literature, literary criticism and feminism. Rodolfo Walsh’s Last Case, her first full-length novel to be translated into English, is published in paperback and eBook by Corylus Books.

Read more

@Elsa_Drucaroff

@CorylusB

Author photo by Héctor Piastri

After escaping English suburbia as a teenager, Quentin Bates has roots in Iceland that go very deep. He’s been a factory hand, seaman, truck driver and (briefly) a teacher, before falling by accident into an obscure branch of journalism. From there it was a side-step into fiction and from there to translating fiction and non-fiction. One of the group behind nano-publisher Corylus Books, set up to bring otherwise unheard voices to English-language readers, Quentin writes in English and translates from Icelandic.

corylusbooks.com

graskeggur.com

@graskeggur

Slava Faybysh is a translator based in Chicago. His translation of Elsa Drucaroff’s short story ‘Lili in Her Forest’ was published in New England Review in 2023. Other short translations have appeared in the Southern Review, The Common and elsewhere. He also translated Leopoldo Bonafulla’s anarchist memoir, The July Revolution: Barcelona 1909.

@slavabob8