It’s coming!

by Deb Olin Unferth

“A novel like no other: an urgent moral fantasia, a post-human parable, a tender portrait of animal dignity and genius.” Dana Spiotta

At stake: the contested objects, nine hundred thousand white leghorn hens, their foremothers brought over from Italy in the mid-nineteenth century and bred in a frenzy ever since. Were they property or individuals? That’s what had to be decided.

—

It was from this farm, don’t forget, that Cleveland had taken Bwwaauk some three months before, when she dropped out of her cage and went walking down the road in search of more.

Bwwaauk had spent her life from the time she was a pullet on this farm.

You’d think that by now with all the genetic meddling, sensory deprivation, and inbreeding, a hundred and fifty years’ worth, that these animals would barely have brains anymore, that their minds’ dials would be set on static, a low hum, refrigeration vibration. You’d think they’d be blank-brained, a collection of impulses and flesh. Indeed some of the hens on Happy Green Family Farm were moronic slabs, but most were not. They all contained within them the DNA, if not the full expression, of the original bird intelligence. Those hardy genes pressed themselves into existence in all kinds of ways, so that most of these hens still had that feral smart-bird spark in the eye, the instinctual Gallus need to flock, wander, arrange themselves into hierarchies, mate, rear, befriend, follow, fly their awkward short flights, bathe and preen in the dust.

Those hundreds of thousands of brains of Happy Green Farm were ticking away in those grim warehouses, crushed into tiny boxes (or crowded into larger boxes in the two so-called cage-free barns), half-smothered and rotting alive in the oppressive air, barely able to spread their wings, unable to look up and see anything but steel and conveyor belts and low-wattage bulbs, pressed up against strangers, beaks half-severed, feet deformed by the wire they stood on day and night.

Bwwaauk had grown up in Barn 8, an old-style A-frame structure, where the cages are piled in tiers on a slant so that when the crap drops through the wire, it misses (mostly) the hens in the lower tiers. Bwwaauk had lived in a bottom-row cage, the worst spot on an A-frame because crap drops on you from above (the system isn’t perfect). The whole jalopy is placed on the second floor of the barn with a large opening underneath. The excrement falls through the wire to a huge open room below called the pit.

Barn 8 was the oldest barn on the farm, built in 1990. Its cages were rusty. In places the wire had corroded and had holes in it, holes the size of a chicken. In most rows if a hole broke through the rust and a hen fell through, she simply landed in the cage below her. The hens in that cage would peck her to death as an invader, then stand on her dead or dying body to give their feet a rest from the wire. But in Bwwaauk’s case, when the ammonia ate through the rust, the hole that broke open was in a cage on the bottom row. So when Bwwaauk fell, she flopped down onto a six-foot pile of excrement.

She landed with a thump. She looked up at the cage she’d just left. The hens in the cage peered down through the hole at her below. They all assessed the situation.

This hen that Cleveland took, whose brain was lighting up, turning over, working, while she looked up at her hen friends in the cage, her brain was in the toil of trying to convey the complex thought, I’ll be back for you, I promise.“

In the wild, chickens have complicated cliques and distinct voices.

They talk among themselves, even before they hatch. A hen twitters and sings to her eggs and the chicks inside answer, peeping and burbling and clicking through the shells. Adult chickens have over thirty categories of conversation, each with its own web of coos and calls and clucks and struts. Chickens gossip, summon, play, flirt, teach, warn, mourn, fight, praise, and promise.

It is this last, promise, that concerns us here.

In a cage situation a hen has little use for most of these categories of conversation. Her vocabulary atrophies or never fully develops – but it’s there, contained within the brain (which stores and processes information differently from the human brain – the bird’s brain is more like a microchip folded inside the cortex, not like the human’s bulky car motor) and will surface when necessary.

So it was that in the moment Bwwaauk turned her face up to the hens in the cage she’d just fallen from, she struggled to communicate, her mind turned on. Winked to life.

There is a particular cheep isolated by bird researchers who specialize in the Gallus gallus. This sound, when tagged onto the end of a vocalization, translates to something like, “It’s coming.” So a mother might cheep to her chicks, “Follow me up here! Danger – it’s coming!” Or if a male is strutting in front of a female and he tacks the cheep to the end of a crow, he might mean, “Passion, food, babies, protection – it’s coming, girl!” In other words, this cheep works as a rudimentary form of the future tense. This hen that Cleveland took, whose brain was lighting up, turning over, working, while she looked up at her hen friends in the cage (hens have long-lasting friendships and can recognize over a hundred other chicken faces, even after months of separation, and they recognize human faces too), her brain was in the toil of trying to convey the complex thought, I’ll be back for you, I promise, not a sentence hens would generally have a lot of use for in or out of cages, since they like to stay close to one another, even in the wild. This particular cheep came to her.

She made the sound of her own name – Bwwaauk – and the cheep, “It’s coming.” Then she slid down the pile of excrement and marched on.

She never did go back, but she sent someone to fetch them.

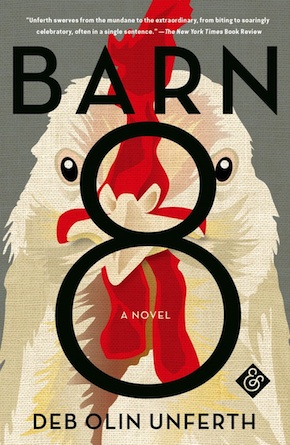

From Barn 8, out now from And Other Stories

Deb Olin Unferth is the author of six books, has received fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and Creative Capital, won three Pushcart Prizes, and was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award. An associate professor at the University of Texas in Austin, she also teaches creative writing at a prison in southern Texas. Barn 8, her UK debut, is published in paperback and eBook by And Other Stories.

Deb Olin Unferth is the author of six books, has received fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and Creative Capital, won three Pushcart Prizes, and was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award. An associate professor at the University of Texas in Austin, she also teaches creative writing at a prison in southern Texas. Barn 8, her UK debut, is published in paperback and eBook by And Other Stories.

Read more

@debolinunferth

Author portrait © Nick Berard