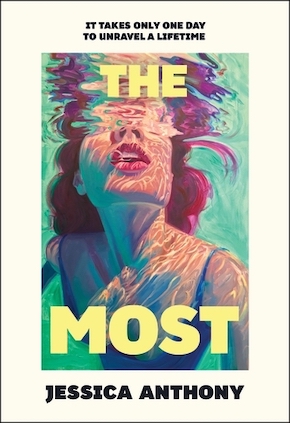

Jessica Anthony: Orbiting the brink

by Mark ReynoldsSet over the course of a sunny November day in suburban Delaware in the late 1950s, Jessica Anthony’s The Most dissects the hopes, uncertainties and secret desires of a married couple whose life hasn’t quite panned out as they’d hoped. Handsome people-pleaser Virgil Beckett drifted into a job as an insurance agent, but is ill-equipped to drive home expected sales, while his wife Kathleen, once a prospective champion tennis player, is reduced to an unfulfilling role as a home-maker and mum of two. On this particular Sunday, as news is breaking about the Russian launch of Sputnik 2 with doomed pooch Laika on board, Kathleen declares she won’t be joining the rest of the family on their usual dutiful trudge to church, and instead decides to take a dip in the apartment complex’s semi-abandoned pool. As she reflects on the malaise in her marriage and her severely abridged ambitions, she is overcome by lethargy and refuses to come out…

—

Mark: Your book put me in mind of Revolutionary Road and My Life as a Dog, and it’s also been compared with Mad Men, Peyton Place and the work of John Cheever, Jennifer Egan, Jonathan Franzen and Taffy Brodesser-Akner. What do you consider were your key influences, and what in particular drew you to writing about this time period?

Jess: When writing outside of my own era, I try to make sense of a time through its literature. I had been reading the work of women writing in the 50s – McCullers, Brooks, O’Connor, Highsmith, Jackson, Childress, Paley – and studying the ways these women were writing women. Clichés that abound from the idea of the contented ‘50s housewife’ have been filtered purely from the fantasies of men’s advertising (there is your Mad Men reference). The literature of the period shows no trace of that obliging, braindead woman. It’s a very odd little mythology that’s endured. To the contrary, the women who reported women in the 50s did so as novelists have always done: by chasing the spectacular singularity of experience that makes a human being, human. So I was keen to write a woman whose agency might startle a modern reader. Like Joy/Hulga in O’Connor’s ‘Good Country People’, stomping around her mother’s house with that wooden leg, bemoaning everyone’s stupidity, or Therese in The Price of Salt, repulsed by the people eating in a lunchroom, or Wiletta in Trouble In Mind, having a riotous time mocking tropes of Black characters in white plays, or Virginia in ‘An Interest in Life’, deciding to solve her problems by going on a game show, I wanted Kathleen Beckett to surprise me with her peculiarity.

How early in the writing did you realise you wanted to condense the action of the novel into a single day, and why?

I knew from the very beginning. The summer I wrote the first draft I was working as a bridge guard in Slovakia, guarding – metaphorically – the Maria Valeria Bridge from being destroyed, as it had been during the two world wars. It was the Slovakians’ belief that the act of creation prevents fascism, so an artist would be there for three months, guarding the bridge through writing. The first week was extremely hot. Temperatures remained over 100 degrees for four days, and I had no air conditioning. Writing was impossible. There is a water park in Štúrovo, with a number of swimming pools. At the end of the first week, I biked over to the pools to cool off. I was delighted to discover that I had an entire lap pool to myself. It was a Sunday. Everyone was at church. I began thinking about bridges between people in a marriage; how a long relationship of any kind exists as a pattern of moments. So I wanted to write a moment out of a couple’s daily pattern or habit; the simple story of two spouses over the course of a single day, and in that day, I would learn everything I needed to know about whether or not the marriage would survive. I was not interested in condemning either party; I was interested in the precarious space between secrecy and individuality. The moment when routine must be upended, and the unspoken must be said. I climbed out of the pool, biked home, and wrote the opening line: “Kathleen Beckett awoke feeling poorly.”

I enjoy the potential of not-knowing in fiction: I discover along with my characters who they are, what they need. Desire breeds conflict. People either receive what they want or they don’t. This creates problems.”

Kathleen simply decides one morning that “normal [is] no longer acceptable”, but she seems frozen in the moment as she refuses to get out of her pool. Her hesitancy keeps the reader guessing how the day will pan out for her and for Virgil. Did you start with just the premise that here is a woman on the verge of a life-changing decision?

I enjoy the potential of not-knowing in fiction: I discover along with my characters who they are, what they need. Desire breeds conflict. People either receive what they want or they don’t. This creates problems. When Kathleen first decided to go for a swim in this abandoned pool, she wanted only to cool off. She was delighted by how good she felt floating in the pool, and so she decided to stay, at least while Virgil and their sons were at church. I enjoyed that I didn’t know why was she staying in the pool. She was making decisions that morning for simple, perhaps slightly hedonistic reasons – but the longer Kathleen remained in the pool, the more time she had to mull over the truth about her marriage, and the more serious her reasons for not leaving became.

The title comes from a winning tennis shot (as well as being the Czech/Slovak word for ‘bridge’). Is the tennis shot your own invention?

I have hypermobility, so my joints are atypically flexible. I can bend my hands into all kinds of odd contortions. When I was about twelve years old, I took tennis lessons, and one afternoon my instructor hit the ball towards me. When I went to return the ball, I swung my arm and my shoulder slipped out of its socket. It is extremely painful to work a shoulder back into place, but while standing on the tennis court, I did it, to the horror of the girls standing around me. While the manoeuvre in the novel is an invention, the sensation of twisting my arm into my shoulder socket on a tennis court is cold memory.

How does the 1950s suburban American Dream compare with your own life experiences, and contemporary life in Maine?

I find it bizarre how people mistake optimism about the 50s with some kind of exemplar of social order, a time when so many Americans had very few rights, and the middle class were largely status-cravers whose identities were formed from whatever car new Mr Johnson had parked in his driveway. Brown vs. Board happened four years into the Fifties. It would be another ten years before Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act. What was working well? The wealthiest were taxed at 90%. We had a robust middle class. Our culture was full of want, but that desire had not yet been corporatized. I imagine my life looks and sounds very different from 50s suburban America. Portland, Maine used to be a working waterfront, but has been gentrified. Outside my window, I used to hear horses carrying tourists around the city on wagons. Now I hear new condo construction, people speaking in therapy jargon. I hear people speaking to their dogs like they are children. It could be said that we are living out the desires implanted in the 50s in exaggerated, outlandish ways.

How would you begin to define the 21st Century American Dream?

Dreams, like religion, and maybe like yodelling, are best practiced alone.

Your previous novel Enter the Aardvark was an uproarious contemporary satire, which happened to be published at the start of the Trump presidency. How would you rate Trump’s contribution to political satire? And can you envisage a normalising of American politics if he is beaten by Kamala Harris in the upcoming election?

If by normalising, you mean that America will remain closer to a democracy than an autocracy, then yes. Trump has proved himself too dangerous to satirize. He has become what he maybe always was: a billboard. An ad. What frightens me about Trump are the huge groups of Americans who seem to think he’s sort of funny, or at least unserious. For satire to work, the subject being ridiculed must possess the potential for humility or shame. Trump once shilled his own brand of chicken by dancing in a yellow suit with people dressed as chickens.

You clearly enjoy jumping between genres and time periods. So what are you writing next?

I am writing a novel. I am keeping it close to the chest, but can tell you that I spent a month in residence at the Fred W. Smith National Library for the Study of George Washington.

What are the most important writing tips you encourage your students at Bates College to follow?

Honesty is always the way into fiction.

Which books and authors have you recently read that you strongly recommend?

I just discovered the writer Adam Ehrlich Sachs, whose new novel Gretel and the Great War is simply outstanding. Laura van den Berg’s new novel State of Paradise is her finest work yet.

—

Jessica Anthony’s previous novels are The Convalescent, Chopsticks and Enter the Aardvark, which have been published in over a dozen countries and featured in Time, Newsweek, Esquire, the Guardian, The Wall Street Journal and The New York Times Book Review as an Editors’ Choice. She is the recipient of the Creative Capital Award in Literature and has been awarded fellowships from the Bogliasco Foundation and the Bridge Guard Foundation. She lives in Maine and teaches at Bates College. The Most is published by Doubleday/Transworld Digital in hardback and eBook.

Read more

@entertheanthony

@DoubledayUK

Author photo by Matt Cosby

Read an extract from Enter the Aardvark

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.

@bookanista

wearebookanista

bookanista.com/author/mark