Knowing who the real monsters are

by Mika Provata-Carlone

“Sarid’s incisive critique of Holocaust memorialisation, the corruption within it and the perverse forms of nationalism it can engender is courageous… Nuanced and subtle at every level.” Los Angeles Review of Books

A crucial juncture in world history was the encounter between the Helleno-Judeo-Christian tradition on the one hand, and the new tenets of Islam on the other. It manifested itself with particularly momentous poignancy on the intellectual plane through a single concept, upon which depended almost everything that mattered: the right to existence itself, cultural, national, sacred, ideological, personal. It involved no less than the image we can have of ourselves, of the world and of the divine. That historical moment or movement was called by various names, revealing each time the slant of interpretation or misconstruction of the question, and all that was (still is) at stake. Iconoclasm, iconodulism, iconolatry, idolatry, iconomachy, aniconism, all became intermingled and entangled terms of erasure, annihilation or expurgation; cultural or deculturating gestures by means of which several power games of titanic significance were played out.

Islam’s resistance to images, which on more than one occasion went as far as outright iconophobia, was due, according to Alain Besançon’s seminal analysis, to its perception of “God’s insurmountable distance [which] renders impossible the fabrication of an image worthy of its object.” The Jewish tradition did have images to start with, of quite extraordinary beauty, art, resonance and eloquence, as can still be seen in the mosaics of the Tzippori (Sepphoris), the Huqoq or the Dura Europos Synagogues, or in the unicum European example of the Canton Schola Synagogue in Venice’s Ghetto. A new, more precise and prescriptive understanding of things, which was articulated and implemented as a result of their own encounter with Islam’s iconoscepticism, also encompassed for Jews a revised relationship with images. Yet Judaic aniconicism stipulates that “it is God’s intimate familiarity” that renders images impossible, almost a hubristic exhibitionism. It is familiarity itself, the personal relationship with God, that is the true reflection and representation. For Christianity, anxious to tread a fine line between old idols and a new faith, that familiarity is what in fact makes images necessary: they are mediators to the divine, not objects of adoratio in and of themselves. For Christians too, image and likeness are contingent upon the closeness of the relationship. Such a premise of proximity and intimacy, of knowability in a particular shape and form, also entails questioning, scrutiny, a process of exploration and understanding, the building, through interaction and exchange, of that I and Thou between man and God. Relationships are dynamic, not static, they throb with life, tension, give-and-take, they demand responsiveness, reciprocity, and even (or especially) self-examination.

The polemics of images emerged again with Calvinism and the Reformation, in a clash this time between Roman Catholicism and successionist movements across Europe – the result of new junctures of self-questioning, of cultural, socio-political, and historical reassessment, even self-negation. Each time an image was smashed to the ground, erasure rather than readjustment of the focus or clarification of the vision would emerge as the dominant force. Why is the question of images, of the right to a reflection and representation of the present and past, the secular and sacred, the distinct historical tradition and individual experience important? Quite simply because the question of the power of images, of true icons and of false, billboard idols, lies at the heart of every totalitarian regime, nihilistic movement, anarchical current in time. In Yishai Sarid’s The Memory Monster many such rip currents, and the subtexts of their historical becoming, run concurrently, resulting in a near-demonic confluence of hermeneutical perspectives, facts, impressions, nightmares, especially revisionist compulsions or even outright assaults.

Sarid sets out to grapple with a monstrous history and the overwhelming effects of its memory – or commemoration; he urgently seeks to know whether reason can defeat monsters.”

The Memory Monster is by no means a straightforward text. It is impossible to classify it as a novel, it would be incorrect to designate it as an essay, misleading to call it a memoir. It is, in fact, a fictionalised yet highly realistic testimony of the desperate effort to both grasp at and fight an image – the image of Jewishness across time, at the time of the Holocaust, in the times of the State of Israel and a global Jewish diaspora. It is a witness account of a soul and a conscience in turmoil, with all the resonance and manifold hues of meaning the word ‘witness’ would have within such a context. Sarid sets out to grapple with a monstrous history and the overwhelming effects of its memory – or commemoration; he urgently seeks to know whether reason can defeat monsters. He would like to create a critical space for the assessment, analysis and diagnosis of brutality, everyday or beyond conception. At the heart of The Memory Monster is an agonising question: is memory itself a devouring Siren, or a wise Athena standing by our side?

The right to an image, however imperfect or even fallible, is key. The Nazi programme of Jewish genocide entailed two critical elements: physical annihilation and total historical erasure. The face of Judaism was to be wiped off the face of the earth, and the Germans’ antisemitic agenda and its implementation were no less than a destruction of the image of Jewish presence, cultural, historical, individual. To exist as a Yellow Star was to have no image, to be a faceless blob in a formless mass; to be an inmate/prisoner/victim in a concentration camp, was to have no human iconicity – no name, no personhood, no existence. To survive the Holocaust, as an individual Jew or as a Jewish people, demanded precisely the retrieval, recollection and reconstitution of those broken-up, smashed, vandalised and negated pictures of a life and history. The effort would be colossal, both in its mental toll and also in its confrontation with yet another monster, namely the historical and cultural dysmorphia and self-loathing imposed by antisemitism and by the non-being of a near-annihilated existence.

The Memory Monster is written in the mode of an intimate confession, doubling up as an official report by a Jewish narrator whose strongest, perhaps distinctive trait is a sense of cerebralised self-alienation, and the inability to belong to a place, a face, a family, a community or a history. It is addressed to an equally nameless, faceless committee, or a superior. The only visuals in Yishai Sarid’s story are the concentration camps and the landscapes of Poland, graphic scenes from the history of the Holocaust, close-ups of objects that tell stories of murder or intimate fragility, of the ruins of the crematoria, of human relics, of the remnants of horror in every shape or form. Also the narrator’s own appearance, which gradually unravels to a deliberate caricature of explicit antisemitic proportions as the story progresses, together with its photographic (existential and eschatological) negative, Aryan iconography past and present.

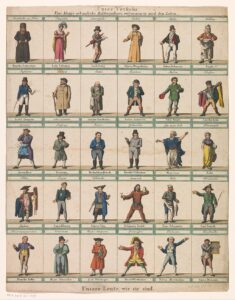

Our Social Circle/Our People, As They Are. Propaganda poster by Johann Michael Voltz, 1819. Rijksmuseum Amsterdam/Wikimedia Commons

The conceit of The Memory Monster is history as a catalyst for understanding, as an instrument for learning, as a vehicle of identity, as a guarantor of continuity and community. Also as a leveller of experience, as an equaliser of trauma and tragedy. The narrator seems to be channelled towards it as a professional career, lured by the power of facts to beat down the false idols of memorialisation, the harpies of doubt, the chimeras of “am I worthy of my own existence?” History “soothed me because everything in [it] was final and complete. Nothing could change. Fictional stories were in the control of a single person’s whims, and made me restless,” the narrator declares early on. He becomes saturated with technical information about the methods and processes of the Holocaust, of the systematic persecution and extermination of Jews, whilst resisting an exploration of the reasons why, of the personal experience of human loss, of the historical and cultural impact on a people. He fights against the memorialising images of the Holocaust he feels are taking over the process of remembrance and critical analysis, against a collective past he deems is creating a mass-produced, falsifying and even oppressive identity. He displays a formidable capacity for cynicism and for a scathing critique of hyper-magnified elements of that salvaged, reconstructed picture, personal or communal, yet he fails to see the larger canvas, the tableau, the true image itself of Jewish presence, in its dynamic flux and flow, its flaws and tragedies, its anxious, fragile humanity.

The sense of disconnectedness is overwhelming – the narrator cannot bring himself to trust in a human response to the horrors he has transformed into a well-rehearsed narrative.”

The narrator’s experience is perforce that of staring at a Gorgon. The monster’s gaze, whether that is the brutality of the Shoah or the agon to exist beyond it, reflects back on him, petrifying human instincts, sensibilities, the critical ability to use that same history he so depends on in order to arrive at a reflected judgement and assessment of facts and contexts, rather than simply extracting the isolated elements that serve to reinforce the sense of disfigurement and deformity, of both conscience and historical belonging, of responsibility towards past and future. The narrator feels a piercing malaise at home in Israel, seeing himself reflected in what he feels is designated there as the Other; he experiences a devastating sense of existential blindness in Poland, guiding groups of students, officials or private individuals to concentration camps, watching their every reaction or even their passivity. The sense of disconnectedness is overwhelming – the narrator cannot bring himself to trust in a human response to the horrors he has transformed into a well-rehearsed narrative. “I was the vessel inside which the story lived,” he says, and the subtextual connotations of that utterance are terrifying: he is a Cerberus guarding the underworld that haunts him, the hell he sees as being both falsified and falsifying.

The narrator’s reactions, his prism of perception, his frame of analysis are highly problematic, unsettling and troubling even, but that is, perhaps, the whole point. The Memory Monster seeks to be an unfiltered transcription of a lost soul in agony, of a Jew whose own image has been smashed beyond repair, and much of it is raw, shocking, profoundly disturbing. It is not easy to find a comfortable readerly position, in fact it is doubtful if any such can be found at all. The strongest point of this de profundis exploration of how to be or not to be a Jew (or in fact a human being) is the seamless interweaving of snapshots of howlingly dehumanised, yet intimately human experience in the camps; the lowest are the multiple false parallels with contemporary history, the distorting blow-ups of actions or reactions, including the role of Jewish prisoners in the running of the camps. The testimonies of Shlomo Venezia, or of Alberto Israel Errera, will hopefully be vivid in readers’ minds, to readjust the focus, straighten the image, clear the vision.

The Memory Monster will not leave anyone who reads it with a sense of either progression or resolution; it ends as much in media res as it begins, as full of ambiguity, blurred or double vision. Yet to engage with its agonising struggle, with its contradictions and crucial, iconoclastic and iconophobic failings, to try and understand why its image is so askew, is not a futile exercise. In fact, it is almost a vital one, involving the reconfirmation of cultural images, of a presence and likeness of the Jewish people and their history and tradition, of a restored personal relationship with all that these stand for. One cannot help but think of the words of Leonard Barkan from his Berlin for Jews: one must live life fully, “haunted, but absolutely honoured, by an indelible past”.

Yishai Sarid was born and raised in Tel Aviv. He served as an intelligence officer for the Israeli Defense Forces before going on to study law at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Nowadays, Yishai Sarid is an active lawyer and arbitrator in Tel Aviv. Alongside his legal career, he has written six novels, which have been translated into ten languages and have won literary prizes including the Bernstein Prize and Grand Prix de Littérature Policière. The Memory Monster, translated by Yardenne Greenspan, is published in hardback and eBook by Serpent’s Tail.

Yishai Sarid was born and raised in Tel Aviv. He served as an intelligence officer for the Israeli Defense Forces before going on to study law at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Nowadays, Yishai Sarid is an active lawyer and arbitrator in Tel Aviv. Alongside his legal career, he has written six novels, which have been translated into ten languages and have won literary prizes including the Bernstein Prize and Grand Prix de Littérature Policière. The Memory Monster, translated by Yardenne Greenspan, is published in hardback and eBook by Serpent’s Tail.

Read more

@serpentstail

Author portrait © Yasmin Sarid

Yardenne Greenspan is a writer and translator. Her translations have been published by Restless Books, St. Martin’s Press, Akashic, Syracuse University, New Vessel Press, Amazon Crossing, and are forthcoming from Farrar, Straus & Giroux. She has an MFA from Columbia University and is a regular contributor to Ploughshares.

@YardenneG

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.

bookanista.com/author/mika/