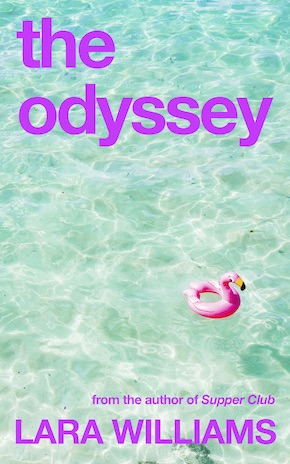

Lara Williams: Lost at sea

by Mark ReynoldsLara Williams’ second novel The Odyssey is a biting satire about a generation cast adrift by the gig economy. Its narrator Ingrid joined the crew of a luxury cruise ship to flee from a failed marriage, and is buffeted between ever-changing roles within a mind-numbing micro-economy which sees her faking it as anything from a gift shop manager to a manicurist, a poolside lifeguard or a croupier. Ingrid throws herself into each role with determined abandon, mostly in order to cast her past and present shortcomings into oblivion. Her social life on board consists of sitting through soulless movies and TV reruns with fellow drifters Mia and Ezra, a brother and sister of indeterminate nationality or drive, and falling into a role-playing game they call ‘Families’ in which the three take it in turns to play mother, father and baby in a heartbreaking echo of actual intimacy. On her rare forays on land, Ingrid wanders alone through nondescript dockside bars inviting drunken scrapes and hollow hook-ups, while on the ship she gets sucked into the captain’s cultish mentoring scheme based around the Japanese notion of wabi sabi, which is centred around the acceptance of impermanence and imperfection. “What you need to understand,” his mantra runs, “is that everything is coming out of and going into nothingness.” Not exactly the life-affirming stimulus to flip her worldview into a more positive mode.

Mark: How would you describe The Odyssey in up to 25 words?

Lara: Heroine Ingrid works aboard a gargantuan cruise ship, where she enrols on a mysterious mentoring scheme run by the ship’s enigmatic captain.

How did Ingrid first form in your mind’s eye?

My first image of Ingrid was her standing alone in a gift shop, looking at a bouquet of flowers that she had arranged. She was the only employee in the gift shop who has been trained in flower arranging – the workers on board the cruise ship are constantly required to undertake training, though she signed up for the florist course voluntarily, she’s a big believer in self-improvement – and I pictured her admiring her handiwork. She suspects she is much more committed and competent than her co-workers, and over time that feeling hardens into a kind of contempt.

What traits (if any) do you share with Ingrid?

Ingrid throws herself into the surreal and dehumanising world of the cruise ship as a mode of escapism, trying to avoid thinking about her real life. She’s seeking a kind of obliteration through work, and I can relate to that craving for obliteration. She also doesn’t trust herself to have full agency over her life, which makes her a perfect candidate for the cult-like ‘mentorship scheme’ run by Keith, the ship’s captain. She basically wants to hand herself over to Keith and abnegate all responsibility. This is an extremely appealing idea to me. Recently, I have been pestering my boyfriend to assume control over my finances because I am useless and spend all my money on stupid shit, but so far he has refused. I don’t think I’ve trusted a single decision I’ve ever made and I’d love to be just told what to do.

How much time have you personally spent on cruise ships – and why?

My parents took me and my sister on a cruise when I was very young. Why? I cannot imagine why. I guess ’cause at the time they were still together and financially solvent and it seemed like the thing to do? I can’t remember much about the trip now. A cruise sounds like hell to me, but also I am now dying to go on one.

What’s the crappiest job you’ve ever had, and how long did you endure it?

Probably a telesales job I had in Stockport, when I was about twenty-two. I say sales, but it was actually ringing up companies offering them free advertising space – and I literally could not give stuff away for free, despite all the sales training and roleplays I had to do before I was allowed to call anyone. Now I look back on it almost nostalgically because I got on with the people I worked with, didn’t have to start till half past nine and ate my lunches in the cafe of this weird cotton museum, surrounded by haunted-seeming figures dressed as Victorians. But also, the guy at the desk opposite me used to openly view pornography on his computer, not even using a small window. Someone reprogrammed my phone so it would automatically ring a BDSM sex line whichever number I dialled. My boss used to log onto my computer to read my emails and occasionally he would come up behind me and massage my shoulders, saying, “Ha ha, Lara hates this.” Plus, I spent all day cold-calling people who were not exactly thrilled to hear from me. I stayed for about six months. I can still remember my last day, walking out of the huge, beautiful ex-cotton mill it was based in, listening to Sufjan Stevens on my phone.

I’m interested in how the gig economy is presented to us like a good thing – a portfolio career! – and how the aspirational lifestyle branding of work has come to replace material rewards.”

What do you regard as the worst aspects of capitalism and a globalised world?

There are so many fresh horrors I’m not sure I can deftly identify the worst, so I’ll just talk about some of the things I wanted to write about in The Odyssey. I was interested in exploring the psychic impact of precarious labour and the rental economy. All the staff who live on the cruise ship are essentially gig workers, moving between roles every few months, constantly having to retrain and recalibrate into new environments. There is a pervasive sense of scarcity, which makes everyone anxiously grateful that they have any work at all. No one owns anything and the ordinary compensations that have traditionally come from work – security, home ownership, family – they are precluded from, and so they have to create artifices of these things. Like: they play a game called ‘Families’ instead of actually building meaningful relationships with one another. I’m interested in how the gig economy is presented to us like a good thing – a portfolio career! – and how the aspirational lifestyle branding of work has come to replace material rewards. I used to live in a flat above a design agency that had a bar in it, and I would walk past at 8 or 9pm, and see all the designers sitting around having a beer, and I would think: it is 9 o’clock in the evening! Go home! It is an economy that demands so much of us and gives so little back.

What is your idea of a perfect holiday or journey?

Now that I have a baby the answer is just anything with childcare.

What is the first rule you tend to drum into your creative writing students?

I don’t think I have any rules I ‘drum’ into students! But I guess what comes to mind is being a reader first.

Does everyone have a book in them?

I reckon so. It is often touted as a cliché of socialism: that it can unleash the creative potential of all, that everyone could write their book. I remember seeing a big blue-tick journalist, I’ve forgotten who, saying something about this on Twitter a couple of years ago: that this does not seem like an appealing offer. I suppose if you are writing and publishing under capitalism, you are more ambivalent about it, because so far it’s working for you.

Who do you count among your literary heroes – authors or characters?

A lot of female short-story writers: Mary Gaitskill, Lorrie Moore, Grace Paley, Shirley Jackson, Anne Beattie, Zsuzsi Gardner.

How would you summarise your lockdown experience?

I went on lots of runs and watched a lot of films, then I got pregnant and had a baby.

Which books have you most recently read and admired?

The last book I read was Larry’s Party by Carol Shields. Carol Shields’ novels tend to take a character and forensically unpack why this person is the way they are; taking quite ordinary, domestic and mundane things and making them utterly addictive.

What are you writing next?

I’m attempting a kind of pregnancy body horror/conspiracy thriller novel.

Lara Williams is the author of Treats and Supper Club. Treats was shortlisted for the Republic of Consciousness Prize, the Edinburgh First Book Award and the Saboteur Awards and longlisted for the Edge Hill Short Story Prize, and Supper Club won the Guardian ‘Not the Booker’ Prize, was named as a Book of the Year 2019 by TIME and Vogue, and has been translated into six languages. Lara lives in Manchester and is a contributor to the Guardian, Independent, Times Literary Supplement, Vice, Dazed and others. In 2021 she was longlisted for the BBC National Short Story Award. The Odyssey is published by Hamish Hamilton and Penguin Digital in paperback, eBook and audio download.

Lara Williams is the author of Treats and Supper Club. Treats was shortlisted for the Republic of Consciousness Prize, the Edinburgh First Book Award and the Saboteur Awards and longlisted for the Edge Hill Short Story Prize, and Supper Club won the Guardian ‘Not the Booker’ Prize, was named as a Book of the Year 2019 by TIME and Vogue, and has been translated into six languages. Lara lives in Manchester and is a contributor to the Guardian, Independent, Times Literary Supplement, Vice, Dazed and others. In 2021 she was longlisted for the BBC National Short Story Award. The Odyssey is published by Hamish Hamilton and Penguin Digital in paperback, eBook and audio download.

Read more

@HamishH1931

@PenguinUKBooks

lara_a_williams

Author portrait © Justine Stoddart

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.

@bookanista

wearebookanista

bookanista.com/author/mark