Laura McVeigh: Journeys of the mind

by Mark Reynolds

“As indispensable as it is timeless… a truly essential read.” Irish Independent

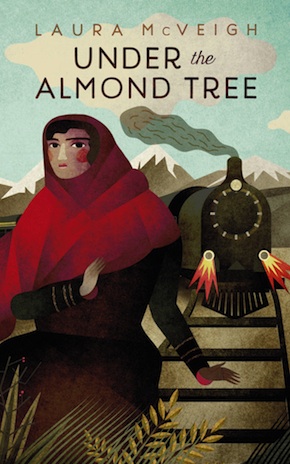

Laura McVeigh’s debut novel Under the Almond Tree is a vibrant and tender modern fable of a young life blighted by war. Fifteen–year-old Samar is displaced from Taliban-controlled Afghanistan and narrates her story from aboard the Trans-Siberian Express as it trundles east and west between Moscow and Vladivostok. With family and memories in tow, as Samar writes in her notebooks, buries her head in Anna Karenina, exchanges stories with fellow travellers and tries to shape a secure future, she is buoyed by the escapism of reading and writing, and the power of love, hope and the imagination. But the terror she is fleeing grows ever more tangible.

MR: First of all, it’s a striking cover and a beautifully made book. Can you tell me a little about the artist?

LM: He’s called Jesús Sotes. He’s a wonderful artist and illustrator, and he really captured the spirit of the storytelling and the aspect of fable and magic realism that there is to the novel. Lisa Highton has a very distinctive vision for each book she publishes – that’s one of the things I really like about Two Roads, it is very bespoke. Lisa and I had talked a lot about the things that mattered to me most about the book, and the vision we both had for the book, and we looked at different artists and his work really stood out.

A large part of the novel is set aboard the Trans-Siberian Express. How did the train become the centrepiece of a novel about fleeing the conflict in 1990s Afghanistan?

For me the novel is about war and displacement in a much wider sense than the conflict in Afghanistan alone, and it was very important to me that I could have that backdrop that can be travelled back and forward, not just through geography but through history, and the sense I wanted to have of how we learn from the past, how we carry the past with us, and seem to keep repeating the same mistakes in terms of our common humanity.

There are all sorts of things that spark a novel. When I was born my parents were very keen on Doctor Zhivago – I was nearly called Lara instead of Laura – so I had an interest in all things Russian, I suppose, from the get-go. I knew that I very much wanted to write about Tolstoy, and in particular Anna Karenina, which is a novel that for me was absolutely instrumental when I was a little bit younger than Samar. So I started the novel with that kind of geography in my head, and then I became interested in really looking at how an ideology can shift and change. I’ve travelled a lot in ex-Communist, ex-Soviet countries, and you see this legacy. In the case of Afghanistan with the Soviet invasion, how Afghanistan was before and during and then to the time of the Taliban, there’s been an incredible shift in a very contained period of time where society has radically changed and then changed again, so that really intrigued me.

I had also seen a whole series of wonderful photographs from the 1960s in Afghanistan, which showed a side to the country I had not been aware of, and isn’t the standard image we have of the country. I come from Northern Ireland, and I’m used to people having an image of a place that is very much at odds with the reality. I found images of people in record shops, I read about Duke Ellington going to play there and, of particular interest to me, the way the women went to university and were able to dress in a different manner. I think almost half the doctors in the country at the time were women, so all those kinds of things really intrigued me, and to think what it’s like to live through that kind of change.

Samar and her family suffer multiple atrocities. As you say on your website, “While I know no one who has undergone all of the experiences that the storyteller of the novel survives, I do know that these things happen in our world and we should speak of them, and that it is through the particular fictions of a novel that we can sometimes glimpse universal truths.” How would you answer critics who might claim Samar’s suffering is too much? Or that a Western writer shouldn’t try to get inside a young Afghan girl’s head?

Having come from somewhere that is very much informed by identity politics, and having grown up with people saying you’ve got to think in a certain way where you’re different to someone else, I think that fundamentally shaped me as a person, and shaped a lot of my choices in terms of the things that I went on to do, and it definitely shapes my writing. For me writing is about the ways in which we are similar and not different, it’s about empathy. I think writing should and does contain multitudes, and should be a bridge to understanding. And if the novel can help do that, and it can help make people think about the issues in a fresh way, that’s all to the good.

It’s very much about family, it’s about hope, it’s about loss, it’s about the transformative power of literature, and I think those are things that, regardless of where we’re from, we can all relate to.”

People have a blinkered idea of what a refugee is, but here’s a middle-class family whose life is completely disrupted, and it’s not so difficult for readers to identify with that.

What I wanted with the book was that it was a universal story; it’s very much about family, it’s about hope, it’s about loss, it’s about the transformative power of literature, and I think those are things that, regardless of where we’re from, we can all relate to.

Samar’s hyperreal journey put me in mind of The Life of Pi…

A number of people have said that.

So which authors, if any, set you on the path to tell this story the way you did?

There were lots of authors that influenced me. You have a lifetime of reading to draw on, so it’s all kind of in there in different ways, but there were a few specifically. I chaired an event, Refugee Tales, at the Edinburgh Festival, and one of the authors, Karen Campbell, had written a very interesting book called This Is Where I Am, which was in my mind. It’s a very different kind of book, but it was writing about those kinds of experiences. Dave Eggers’ What is the What moved me intensely, I found it remarkable, and it just made me feel a little more that this was a topic I wanted to explore for myself. And obviously Tolstoy was a big influence as well, and that’s something I wanted to write about in the novel.

You’ve said that travelling on that train made you realise that East and West are not polarised, but “one continuous land surface which borders, peoples and ideologies have criss-crossed over the centuries.” Where else have you visited en route, and in Afghanistan and Central Asia?

I’ve spent a lot of time travelling in general, and I’ve been to quite a few of the places in the novel. I haven’t been to all of them, I haven’t been to Kabul, and it’s also fair to say that the novel is set in the 1960s through to the 1990s, and I certainly wasn’t doing any travelling then. But I think I have experience both in terms of my own travels and the research that I’ve done to have a good sense and grasp of the subject.

Did working for PEN International and the Global Girls Fund take you to these areas?

I travelled with those roles, and before that I also worked on youth and education issues. I’ve volunteered on international issues, studied global politics and all of that, so it’s something that I’ve been immersed in in many different ways. Certainly with PEN I travelled quite a bit.

And now you’re a full-time writer, are you still a campaigner?

Yes, very much so. Girls’ education is something that’s always mattered to me a lot, and I think that if the book can help on that issue, then I will be very proud of it.

Montserrat is also called the Emerald Isle, and it’s absolutely fascinating. The welcome board as you come out of the very tiny airport says Céad Míle Fáilte, and many Irish customs are there.”

You recently completed a round of edits on your second novel The Plantation House. What are its themes, and when can we expect it to come out?

That’s quite a different book again. Though it is, I suppose, asking the same fundamental questions about what we can learn from the past, how the past shapes us, how does it live in the present? It’s a story of slavery and enslavement and it was inspired, again, by lots of different things. But in particular I was reading about Cromwell and the campaign to rid Ireland of the Irish, and I came across these accounts of children being sent to the Caribbean, and I became very interested in that because it was not something we’d ever been taught about in school. I had also stayed at an old plantation house out in the Caribbean, and had been very affected by that, and intrigued by what the past would have been. Then I travelled to Montserrat, which is also called the Emerald Isle, and it’s absolutely fascinating. The welcome board as you come out of the very tiny airport says Céad Míle Fáilte, and many people and places there have Irish names, many of the Irish customs are there. It’s really intriguing, and I very much wanted to explore there and to write a story about those connections. So that’s where The Plantation House came from. One story goes from seventeenth-century Ireland out to the island, and another story alongside runs from the 1960s through to 2010, beginning with the daughter of the family that owns the plantation house.

Is it practically finished?

When is a story ever finished? It’s a very philosophical question. I am happy with it for now, but I fully expect it will go through many, many more iterations. But my publisher will read it fairly soon.

Has a publishing date been set, or is that still to be decided?

We’ll just see what Lisa makes of it first of all, I think.

It was your quickfire resumé of the second book that got you noticed by Curtis Brown. Could you tell that story?

I had written Under the Almond Tree, and I’d sent off a very early first draft to Mslexia’s novel competition and then set it aside and started working on The Plantation House. I was writing one morning and I had Radio 4 on and they were doing a piece about PitchCB, which is this really great initiative Curtis Brown do. You can tweet your story idea, and different agents read the tweets during the day, and if anybody is particularly interested and wants to find out more, they will favourite it and that means you can send your work in for consideration. I thought it was an interesting challenge so I wrote a tweet about The Plantation House and sent it in, and Jonny Geller favourited it. So that happened, and I thought, well that’s very nice, but obviously I didn’t rush to send in The Plantation House because I was very much still writing it. Then Under the Almond Tree was longlisted for the Mslexia competition, and at that point I thought I really should talk to a few people and see if anybody would like to represent me. I spoke to a very small handful of people and had a really great response, and went to meet Jonny, who said, “Why didn’t you tweet this one as well?” And that was that.

And everything’s happened fairly quickly since. It was around this time last year that you signed with Two Roads, and here’s the finished book.

I suppose in publishing terms that is pretty quick, but it does seem slow when you’re on the other side of it and you’re already halfway through a third book. It’s strange to travel back to it, in a way.

One thing that’s certainly happened quickly since is the many foreign editions that have been signed up [nine languages at the time of writing]. Are you comfortable enough in any of those languages to work closely with the translators?

Well I speak French and Spanish pretty fluently, I studied both of those and I’ve lived in countries where I’ve used them for work, and I can read Italian and make a stab at a couple of other languages. The German publishers, for example, have already had the book translated, and I worked with the German translator a bit on that. Translating is such an art form and you’re not just translating the words on the page, you’re trying to understand the things that the author wanted to convey, so I’m very happy to be available to people to answer any questions they have.

I’ve listened to part of the audiobook, and Rasheeda Ali really seems to have captured both Samar’s youthful zest and her vulnerability. At the start of the recording process, were you given sample readings to select from and approve?

I did listen to sample recordings beforehand, and worked with Lisa to agree which voice we felt was right for the audiobook, and then, you know, she’s a professional, we just let her get on with it. I haven’t heard it all yet; I’m looking forward to hearing it. It’s a very difficult thing to do, because it’s not just the voice of the narrator, but obviously all the other characters in the novel, and it takes a lot of skill to pull something like that off.

You’ve also been working on screenplay adaptation of the novel. Is this on spec, or is the book signed up with a production company?

I’ve started working on the screenplay, and that was something I had really wanted to do from the beginning because when I write I tend to see what I write, and I use the language of film a lot. It’s a good challenge to work on your own original content. I’ve spoken to different producers and people, and we’ll see where it travels.

One particular challenge is that Samar sees as she writes too. Are you putting in hints as to how a director might deal with events that may exist only in her imagination?

When you write a screenplay, I think one of the best ways to go about it is to try and write as if you’re the film editor rather than the director, so that’s what I’m trying to do. The director will obviously bring their own take on it, so I try and do it from the perspective of the editor. One of the things I didn’t want to do was to just slavishly follow the narrative of the novel. If someone else was writing it, they would take all sorts of licence, I’m sure, with how to structure it. You have to find a different way to do it that suits the medium, and that’s part of the challenge and the joy of writing it in a new form.

How do you divide your time between London and Mallorca, and how did both cities become home?

I studied in Cambridge then started my working life in London after college and, like many people, ended up staying. We divide time based on really just as much time as we can spend in Mallorca as possible. I have a young daughter, so we have to fit her around that. It’s a place I love and have visited a lot, and I just think it’s very special. We live up in the mountains and it’s very, very beautiful.

Do you do most of your writing there?

I write anywhere.

And every day?

Sometimes I’ll take a break for a couple of weeks, but most days I write, and I find it a very peaceful place to write, and I certainly did quite a lot of the writing, and the rewrites out there.

A lot of people talk about writing and being a writer but they don’t write, and I think that those who really persevere and stick with it will find their voice and find their audience.”

What would be your key advice to writers who are starting out and trying to get their work noticed?

I think having faith in your own writing is really important. A lot of people hesitate and are sometimes afraid to put it out there. There are lots of routes to connect with people about your writing, so it’s finding out what those are. There are some wonderful writing competitions, particularly for novelists but also short-story writers, there are many wonderful magazines and salon events, and all sorts of places that are open to emerging writers to come forward and share their work. A lot of people do writing courses, which are not always accessible to everybody, but if that’s something that can be helpful, why not? And I think just not to give up – and to keep writing. A lot of people talk about writing and being a writer but they don’t write, and I think that those who really persevere and stick with it will find their voice and find their audience.

You mentioned that you’ve started a third novel. Can you say anything about it at this point?

I never talk about them – not very much anyway – while I’m still writing, because I find that just takes all the energy out of the process. I’m about halfway through at the moment, and it’s a different kind of book again to the first two and I’m really enjoying writing it.

Laura McVeigh grew up in Northern Ireland and read Modern & Medieval Languages at Cambridge. Previously Director of PEN International, she has travelled widely campaigning on freedom of expression issues around the world. She also served as Director of The Global Girls Fund. She lives in London and Mallorca with her family. Under the Almond Tree is published by Two Roads. Read more.

Laura McVeigh grew up in Northern Ireland and read Modern & Medieval Languages at Cambridge. Previously Director of PEN International, she has travelled widely campaigning on freedom of expression issues around the world. She also served as Director of The Global Girls Fund. She lives in London and Mallorca with her family. Under the Almond Tree is published by Two Roads. Read more.

lauramcveigh.wordpress.com

@lcmcveigh

Author portrait © H Dawber

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.

@bookanista