Megan McCubbin: Wild in heart and soul

by Mark Reynolds

Megan McCubbin, a familiar face to viewers of the BBC’s Springwatch and Animal Park, is a passionate and eloquent champion of wildlife and one of Britain’s foremost young naturalists. Having grown up in and around the Isle of Wight Zoo, and travelled the world on assignment with step-dad and now fellow Springwatch presenter Chris Packham from a tender age, there was little question she would go on to study Zoology and become a vocal science communicator and biodiversity activist in her own right. With An Atlas of Endangered Species, she sets out to inspire the next generation of environmentalists by encouraging an informed appreciation of the natural world and plugging in to the sense of wonder she experienced herself when growing up – and to get families talking about extinction and conservation.

“I think it’s very important to encourage young people to step outside and just notice what’s on their doorstep first of all,” she tells me via Zoom during a break in filming for the next Springwatch series. “I had an amazing experience the other day just listening to a blackbird singing for about half an hour, and the amount of joy it brought me was exactly the same as if I was watching elephants in Africa or penguins in Antarctica. So it’s about appreciating the wildlife we’ve got on our doorsteps – robins, blackbirds, earthworms, stag beetles, ladybirds, whatever it may be. I wrote the book from a personal perspective about some of the encounters I’ve had with wildlife in the UK and around the world. I tried to keep it a mixture of some of the big megafauna groups that people definitely know, and some they definitely won’t. So it’s about bringing awareness for some loved and under-loved species, but also highlighting a need for action and a need to use our voice to help scientists and rangers on the ground, and to keep protecting our species. It goes beyond just putting species on an endangered list, we can’t keep adding more species, it’s got to be about taking them off.”

Having struggled with dyslexia as a child, Megan was very particular about the book being accessible to people with reading difficulties, not only in terms of choosing open fonts and layouts, but also by using a narrative style that feels like she’s in direct conversation with you as you read.

“I’m glad it comes across that way,” she smiles. “When I was younger I had a real anxiety and fear around books. I can remember being sat in an English class or at home on a birthday being given a book and I would genuinely feel very stressed, I would feel like I’d failed even before I’d opened it because I knew I wouldn’t be able to digest the information as expected, or as quickly as others would want me to, and the letters would move around on the page or it wouldn’t be the right colour or the texture of the paper would feel really odd. All these different things would just use up a lot more energy for me when it came to consuming information, and it took a while for me to learn that it wasn’t me that was failing, it was just that the books I’d been given weren’t thought about for dyslexic people, or for anyone with visual struggles. For example I gave the book to my nan and, bless her, she’s got problems with her eyes, she reads on her Kindle because she can no longer read books on paper, but she was able to read my book, which I was really happy about. So I hope even for neurotypical people that it’s accessible and easier on the eye. I just felt that if other books were written and styled in this way then I might not have had that fear and anxiety, so I hope that young people with those difficulties don’t feel the same as I did, and are thought about more in publishing.”

I’ve never seen a colour book like it before, combining adult themes with beautiful illustrations. We were really lucky to get Emily, she worked really hard on getting it right, capturing movement and behaviour.”

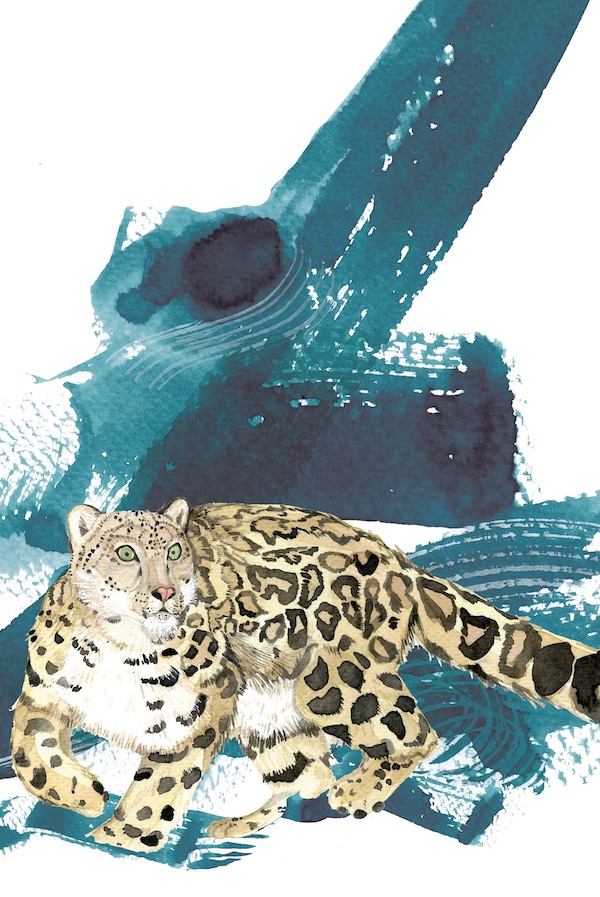

Cementing that user-friendliness, the chapters open with beautiful illustrations by Emily Robertson depicting each of the twenty species under consideration. “It was a long process, talking about illustrators,” Megan recalls. “We knew some of the themes would be somewhat hard-hitting. Talking about endangered species, obviously it’s hard to keep it upbeat all the time because you have to talk about why they’re endangered. But we knew that to counteract that it would be lovely to have some really colourful, vibrant illustrations, and I think that’s exactly what Emily brought. Honestly, I have no idea how she does it, but she brings these animals to life. I’ve never seen a colour book like it before, combining adult themes with beautiful illustrations. We were really lucky to get Emily, she’s very talented and worked really hard on getting it right, capturing movement and behaviour, whether it’s the orangutan in the tree, or the orcas jumping through the waves, which is one of my favourites.”

Megan writes vividly about travelling to Kenya at the age of six and seeing vultures, jackals and hyenas feasting on the carcass of a giraffe; and about watching a pair of albatrosses in a courtship dance off the tip of South Georgia on an Antarctica expedition when she was ten.

“I was incredibly fortunate that I was able to travel from a really young age,” she reflects, “and to go to remote parts of the globe and meet amazing communities and see species that were beyond my wildest dreams. My stepdad Chris Packham has travelled the world a lot for his work, and any opportunity he got to bring me along, I was there with him. So I kind of grew up travelling with film crews. We didn’t do typical holidays, it was always a working trip or an educational trip. There were no trips to the beach – or if I did manage to get to the beach it was for an hour to look at a wader, which I loved and continue to grow to love more and more as I get older. So I was really fortunate to be able to travel a lot in my younger years, to India, to the Arctic, to see family in Canada, to parts of America. I’ve since worked in the Bahamas and in China, some far-flung places around the world, and those experiences really opened my mind. I’ve seen climate change, I’ve seen species decline. Every year, for example, we would go to The Gambia, and I’ve seen bird species decline there year on year. I’ve been to Antarctica a number of times and I’ve seen glacial retreat. So that is a massive motivator for me, having seen it first-hand, to get the word out there and to talk about these things. I’ve been so lucky to go to these places, that now it’s my duty to do what I can to protect them.”

Probably the toughest part of compiling the book was winnowing it down to just twenty species. “That was a tricky one,” she agrees. “I knew there were some key species I wanted to cover. I’m really into sharks, for example, so I knew I wanted to get sharks in there, and I knew I wanted to talk to one of the scientists from the Shark Lab, where I went and studied for a long time. Other than a few key species that I knew about, I wanted to learn as much as hopefully the reader will learn when they’re going through the book. So I opened it out, because obviously you don’t know what you don’t know. I put a shout-out on Twitter and I asked people, “Do you work with a globally endangered species, and would you be willing to give up a couple of hours of your time to talk to me?” and the response I got just from one tweet was remarkable, I was astounded by the number of people that got in touch from all over the world. Then it was so hard to choose, there were thousands of others I could’ve gone for, but I went for scientists I looked into where I thought the work was really engaging or different, and I wanted to make sure I had a bird, an insect, an amphibian – and it’s an atlas, so I wanted to make sure they were distributed all around the globe. But there were some stories that just really spoke out to me, and obviously it could be a never-ending book if I were to do all of them. But I chose the ones I was really fascinated by, some that I didn’t know much about and I wanted to learn about too, but they’re all unique stories in their own right, I think, there’s not much overlap between them.”

I’ve seen climate change, I’ve seen species decline, I’ve seen glacial retreat. I’ve been so lucky to go to these places, that now it’s my duty to do what I can to protect them.”

One surprising inclusion is the glow-worm which, although not officially classified as endangered, has suffered a staggering three-quarter population loss in the UK since 2001. It is a victim of what’s become known as the ‘insect apocalypse’, which is a result of agricultural practices that have led Britain to becoming one the most nature-depleted countries in the world. So how have we largely overlooked that fact until now?

“I think ignorance is bliss, in many ways,” says Megan. “And also there’s a phenomenon called shifting baseline syndrome, which explains how every generation gets used to the current environmental norms and accepts that as the way things ought to be, or have always been. I can talk to my grandparents and they’ll tell me stories about how they’d walk through Southampton, where I grew up, and there would be flocks of starlings everywhere; my granddad can remember nightingales singing in the city; my nan grew up in Norfolk and there were red squirrels over there. But I don’t remember that, that’s not my reality, therefore it’s not my normal. Because we get so used to how things currently are, we forget what nature should actually be. When we’re travelling through the countryside we see expanses of fields, we see plantations and we see greenery, and we think ah, green is good, because we’ve been greenwashed to think that way. But actually when you look at it, a lot of it is a monoculture, a lot of the trees that are planted are non-native and just for commercial use and not our ancient woodlands, which is a habitat we have lost and continue to lose. So we’ve got to change the narrative about what our natural world should be. We tend to bury our heads in the sand because it’s such a big, overwhelming problem, and actually we’ve just forgotten. We’ve got so used to over-managing, and we say, well our fathers did this before us, and their grandfathers did this before us, but if you go further back that never happened. So this idea we’ve got of traditionally over-managing our land is something that is still relatively new, and we need to scrap that and tackle shifting baseline syndrome head-on.”

In one of the many memorable passages in the book, Megan examines the extent of the microsystem of insects, fungus and algae that live in the fur of a sloth:

Sloths are solitary animals by nature, but when you take a look at what lives on them in the microcracks of their fur, you’ll find a whole ecosystem of moths, beetles, parasites, arthropods, fungi and algae, some of which can be found nowhere else on Earth other than on the back of a sloth. It’s a symbiotic, mutually beneficial relationship; these organisms have a safe place to live while the sloths are not only visually camouflaged – thanks to the photosynthetic algae tingeing their fur green – but it also helps them remain inconspicuous in the olfactory sense, as it means they smell just like the jungle they live in.

“How cool are sloths! Sloths are amazing!” she buzzes. “I feel like there’s a documentary to be made about the ecosystem on a sloth’s back. You’d need a very patient sloth and a good micro lens. But yeah, it’s fantastic. And the thing I liked about the sloth chapter was that actually I learnt so much. Yes of course they’re incredibly slow and their metabolisms are slow, but they’re slow for a reason. And how amazing is it that the algae turns their fur green so that they smell like their environment, because obviously they can’t run away from predators. It’s just mind-blowing. I knew a little bit about the fact that moths were on the sloth’s back, I think that’s been covered in one of the Attenborough documentaries, but I didn’t understand the extent to which there is a community on a sloth’s back. The scientists have known for a fair little while, but we don’t cover sloths as much as we should, I think.”

When you’ve got poachers on the ground who are trying to get away with bad business, trying to shoot a rhino or whatever it may be, the last thing they want is birds circling right above their illegal activity.”

In the white-headed vulture chapter, there’s a heartbreaking eyewitness account by Campbell Murn of the Hawk Conservancy Trust about a poachers’ tactic known as ‘sentinel poisoning’. Megan takes up the story: “Vultures are phenomenal birds, they are of course largely scavengers, and they have the most acute sensory system to be able to detect a dead body very, very quickly, so they’ll go down and consume it, and all these different vulture species each have a different specialism. Some will go after the meat, some will then come in later and have the bone, so they really are nature’s clear-up systems, and they are so fundamentally important. But depending on the species, whether they’re visually finding the dead animal, or smelling it, or going off the behaviour of other vultures, what they do is they start circling. And when you’ve got poachers on the ground who are trying to get away with bad business, trying to shoot a rhino or whatever it may be, the last thing they want is birds circling right above their illegal activity. Rangers for a long time used vultures to their advantage – the moment they see circling, they’ll go and check if it’s a poaching incident, and vultures have given the game away for quite a lot of poachers in the past, so poachers have started to lace decomposing bodies of buffalo or zebra with poison so that vultures will come down and eat the poison, which then not only goes through the vultures but goes through everything else as well – lions and hyenas and jackals that come up, it goes into the whole ecosystem and you’ve got a huge poisoning event on your hands, it’s an ecological catastrophe. So it’s basically poachers trying to cover their tracks, so the vultures don’t give the game away.”

Another alarming fact is that pangolins may account for as much as twenty per cent of the illegal wildlife trade because they’re just so easy to pick up when they’re intimidated and roll themselves into a ball to protect their soft underbellies. Can we expect a good news story about the pangolin anytime soon?

“I’d like to think so,” Megan insists. “At the moment the demand for pangolin scale in traditional medicines is still quite high, but we are becoming better at detecting it going through customs. The demand is still there, but I think that is going to change with generational turnover. A lot of people that consume pangolin scale or any traditional medicine tend to be of an older generation, so we are starting to see that flip, but how quickly that can happen and whether pangolins can recover remains to be seen. The more we can learn and the more we can do to reintroduce the confiscated pangolins, the better chance they’re going to get. But security is quite tight around areas where there are pangolins, and for good reason.”

The final choice of species in the book is humans. Again not strictly endangered in anything like the immediate term, but since almost every species that has ever existed on Earth has been wiped out over time, the question remains, “Will we be the animals that consciously destroyed the planet as we knew it, or the ones that learned from our mistakes and managed to turn it around at the last second?” So how hopeful is Megan about zero carbon targets being met to tackle climate change, and what more could Britain in particular be doing?

“Well, what we could be doing is not investing in new coalmines. That would be a good start. There was an IPCC report that said the two things we have to do to reduce climate catastrophe are to move away from fossil fuels to invest more in renewable energies, and to stop investing in fossil fuel infrastructure, and we are currently still doing both, we are commissioning new coalmines and still pumping out greenhouse gases. Yes, things are starting to turn slightly. As I say in the book, more people are now employed in the renewables sector than in the fossil fuel sector, which is good, but unless we have major investment into that transition and major support, then I am greatly concerned. But I have to stay hopeful. I genuinely have to stay hopeful, doing what I do, because I can’t keep fighting if I’m not. And there are steps of progress, it’s just those steps are small and we need to listen to the scientists. I say this all the time, we made law and regulation and policy, it’s a man-made thing and it is important, however if that policy can’t be flexible with updated science, then what’s the point? If we can’t update our own laws and regulations easily with updated knowledge, then something is going terribly wrong. And at the moment scientists are being ignored, or listened to so that politicians can look good but then nothing’s acted upon. It’s infuriating because these people are spending all their lives trying to protect endangered species or understand climate change to try and influence policy, but that policy just isn’t changing, it’s like it’s stuck in concrete. So I am hopeful, but I think we do need major action. There’s only so much that individuals can do, and I’ll always say that individual action is important, but I’m getting to the point now where I just think the most important tool that we have is our voice, and we have to hold our politicians and big companies to account, and insist that they lead the way. We are seeing businesses transform, but we need to speed up that process, and we need to get the government on track.”

My advice to anyone looking in on those protests is don’t judge it until you’ve been there. I think of it like a festival with purpose, it’s a really positive space, a real empowering moment to be involved in.”

We also have to learn to be more careful about the stuff we consume. Palm oil is used in up to fifty per cent of all items sold in supermarkets, from food to toiletries, cosmetics, and even clothing, and usage can surely be reduced to prevent the destruction of wild habitats to make way for palm oil plantations. Squalene, or shark liver oil, is still very widely used in cosmetics, and around 3,000 sharks are killed to collect every tonne. So what should be used instead, and how do we identify and avoid using products that contain these things?

“With palm oil it’s really tricky because as a crop the palm oil tree has a really high yield, and other plants would take a lot more rainforest, a lot more deforestation to harvest the same amount, so it’s a challenging question. But Indonesia is moving really well in limiting and trying to halt deforestation entirely, and keep up soil health to regenerate palm oil plantations where the damage has already been done. In the last year they’ve been taking steps to really reduce that damage, so I have to commend Indonesia for that, and now other producer countries need to follow. I always try and buy palm-oil-free. Some manufacturers make claims for sustainable palm oil, but I hear differing reports about how effective and sustainable it really is, so I try not to buy it. I don’t have the answer about what alternatives there are, other than just trying to change our diets and eat less processed food, which would be healthier for all of us. Chris van Tullekin has just released a book called Ultra-Processed People, and it’s the most enlightening, quite terrifying book I think I’ve ever read. I’ve read a lot of books on the climate, and this book is absolutely petrifying because it tells you all about the kinds of foods we’re putting in our bodies and the chemicals and the oils and everything, and now there’s a lot of food I used to eat that I will no longer eat. But palm oil is an ongoing discussion, I would say. Squalene, on the other hand, there are plant alternatives, it’s as simple as that. We don’t have to use squalene, we don’t have to be taking sharks from the deep sea and using their oil in our face creams. It’s like the bear bile phenomenon, we don’t have to use it, there are plant alternatives out there, so that one’s just black-and-white for me, I find it really bizarre that we’re putting oil from deep-sea sharks on our bodies. Nuts.”

Another thing we can all do as individuals to make our voices heard is to take to the streets in protest, especially at a time when the government is introducing new laws to criminalise disruptive tactics and joining the right-wing press in condemning groups like Extinction Rebellion and Just Stop Oil as lawbreakers and trouble-makers. So where should we draw the line between the lawful and the disruptive?

“The people behind these organisations aren’t anything like as they are portrayed in the media,” says Megan, “they’re professors, they’re teachers, they’re highly intelligent people that know what they’re talking about, and they’re there because they’re frightened and angry and no one else is doing anything. They don’t want to stick themselves to pavement, they don’t want to cause disruption, but they don’t feel like they’ve got any other choice to make people listen and they tried everything else, they tried petitions, they tried talking peacefully, what is there left to do? So at what point does it become morally acceptable to break certain laws, if those laws are unjust and are ultimately leading to the demise of our environment, our species and ourselves? We have to ask ourselves those difficult questions. I was recently at The Big One in London for a couple of days, where over a hundred organisations came and stood shoulder to shoulder, and we had the biodiversity march on the Saturday, which was a peaceful, family-friendly event, no civil disobedience. And Just Stop Oil and Extinction Rebellion are changing their focus, they’ve done civil disobedience. If it gets desperate they’ll do it again, but they want to get more people onside, they want more people to understand, so they’re trying to change their tactics a little bit, to be more inclusive. But my advice to anyone looking in on those protests is don’t judge it until you’ve been there, because a lot of the time the narrative skews what’s really happening. I think of it like a festival with purpose, it’s a really positive space, a community space where people really support each other, even when talking about the gloom and doom of climate change. It’s a real empowering moment to be involved in, and every time I’m there I genuinely feel a weight is lifted off my shoulders because I think, thank God someone is doing something, whatever their methods, and that’s got to be respected.”

—

Megan McCubbin is a zoologist and TV presenter with a particular interest in animal behaviour, evolution and the illegal wildlife trade. She studied Zoology at the University of Liverpool, specialising in primate behaviour and conservation, and has worked in China as a behavioural specialist for the charity Animals Asia, which rescues and rehabilitates bears trapped in the bear bile farming market. She has also spent time volunteering for Africat in Namibia working on big cat conservation and teaching environmental education workshops, and spent five months working alongside leading scientists at Bimini Biological Field Station (Shark Lab) in the Bahamas. Megan is co-author with Chris Packham of Back to Nature: How to Love Life and Save It (Two Roads, 2020). An Atlas of Endangered Species is published by Two Roads in hardback, eBook and audio download, read by Megan.

Read more

meganmccubbin.com

@MeganMcCubbin

meganmccubbinwild

@TwoRoadsBooks

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.

@bookanista

wearebookanista

bookanista.com/author/mark