Peter Buwalda: Expect fireworks

by Mark ReynoldsIt’s often assumed that first-time novelists only write about what they know. Ahead of meeting Peter Buwalda I try to dismiss any notion of encountering a judo blackbelt, mathematical genius and jazz buff with paranoia and jealousy issues, a murderous streak and an internet porn habit, as might be inferred from the characters he portrays in the gripping and accomplished Bonita Avenue.

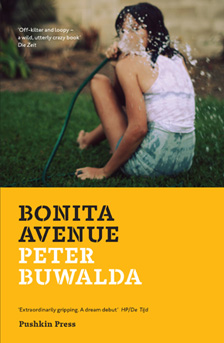

The novel is an intimate family saga set in Holland and America, built around a tense triangle between maths professor and politician Siem Sigerius, his wilful step-daughter Joni, who sees an opportunity to make serious money from a personal porn site, and her troubled boyfriend Aaron. It is also a sweeping satire and a psychological thriller that, in the words of the judges of the AKO Literature Prize: “Puts the reader in a headlock and drags them from climax to climax.” So did he set out to write a novel that defies classification in a single genre?

“It’s an interesting question because writing it I can remember the moment when I was wrestling with the whodunit,” Buwalda recalls. “If I did not reveal a suicide in the first chapter, for instance, then it could have turned out to be a whodunit, and that’s something I really didn’t want to happen. I was aware of genre and I wanted to make something like literature, but I wanted it to be plot-driven at the same time, so it was more like a hybrid between a thriller and a character novel. Some writers I admire are capable of making something that’s truly literature but also a page-turner, and finding that optimum between the two is something I was very aware of trying for.”

The novel has been frequently compared by reviewers and publishers to Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections, but Buwalda is quick to refute that Franzen’s book was any kind of direct influence.

“I can’t take it as an influence, no. It’s brilliant, but it isn’t plot-driven, for instance, it is more like getting up with the characters and living their real lives – and real life isn’t plotted. I can’t name one or three authors who were an influence; it’s more like a bunch of fifty or forty important writers who are all different and all have their merits.”

I suggest that Joni is a Lolita for the internet generation – but Buwalda insists that his first intention was to explore male sexual identity.

“I wrote the novel because of the influence the internet had on the sexual behaviour of young boys. I was thinking, what has the internet changed the most, and if I was an adolescent in 2005 instead of 1985, it would undoubtedly be the directness and availability of porn on the internet. Not only porn, but other information too. The internet makes the younger generation more wise than the elder, for the first time in history I guess. So that was the reason to write about it. I think Lolita is more an aesthetic work of art which I don’t associate with porn.”

But certainly Joni is coquettish in the same way as Lolita; she clearly understands her sexuality and the power she has to manipulate boys and men.

“Joni is in charge of what she’s doing, that’s true. I wanted to depict her as the strongest persona of the three protagonists. Sigerius is suffering from his moral convictions – in condemning what she’s doing, he’s trapped in his own moral thinking; Aaron is only in it because of weakness and jealousy, he’s continuing because he’s afraid somebody else will take his role; but Joni is aware of everything and she has a plan, she decides ‘I want to do this’ and that makes her maybe a kind of Lolita-type person, yes.”

The key events take place against a backdrop of the dying embers of ‘Third Way’ politics in which charismatic, flawed leaders like Clinton, Blair and, in Holland, Wim Kok, turned out to be less than invincible. What attracted him to writing about this era?

“It’s more a coincidence that I had to position the story in that political period,” he reflects, “because what I needed was the first bubble of internet growth. It was necessary that Joni was a pioneer, one of the first who saw that there was a short, easy way to make a lot of money by selling herself without being a prostitute. So that was the reason to take 1995, 1996 as the starting point, not because of the leaderships of Clinton or the others… except for one thing: Sigerius’s struggle with on one side his son who committed a murder and his daughter who is selling herself online. Clinton had the same problem. He was on one hand bombing Serbia and causing collateral damage and the deaths of civilians, and on the other he had the Monica Lewinski scandal, and the public was more upset about Lewinski incident than about the violent and perhaps criminal activities. Sigerius has a son Wilbert from a past marriage who is an outright criminal, while Joni does something you cannot be charged or put into jail for, but he is more upset about that, and that’s interesting.”

One dramatic real-life event that’s depicted is the Enschede fireworks explosion of May 2000, which almost didn’t make it into the book.

“In the first draft of the novel I left it out,” he explains, “not knowing, or remembering it was in that year. Then a little light started burning in my head – what was happening in the year 2000? And when I realised it was the year of the Enschede disaster I had the problem that I’d written a realistic novel – everything in Enschede, the streets, the people, the university, is depicted as it is in real life – so I had to do something with that disaster. I had three choices: I could move the story to 1999, but I felt that would be like writing about Hiroshima one year before the bomb; or I could move everything to another technical university, like Eindhoven or Delft, but that was such a big thing to do because I know Enschede; so I decided, OK I have to bring it in, but then I had to make it interesting for the novel. And it turned out to be an important metaphor for everything that is going wrong in the family – the explosion in Enschede foreshadows the explosion within the triangle of Sigerius, Joni and Aaron. In the end I’m very happy I put it in, because it’s a very strong part of the novel now, it sets everything in sharp focus, it moves the plot forward – the return of Wilbert, for instance, is initiated by the fireworks disaster because he starts thinking, hey, is Joni still alive? Then Aaron and Joni are forced to be together in Sigerius’s house because of the evacuation… so it was very useful and helpful in the end.”

It’s documented that Buwalda took four years to write the book, and I’m curious to know if this was this a full-time project, or if he was fitting the writing around other work commitments.

“It was completely full-time. Actually I worked four-and-a-half years on it, maybe five, of which four were full-time after I quit my job. I had a good contract and an advance that was enough to keep me going. I quit the job, I got the contract on the last day of my job, I went home for the weekend, and on the Monday I sat down in front of a white screen. So it felt very frightening in a way.”

Sigerius is such a dominant figure in the novel, I ask if he was the first character he wanted to build the story around, and whether he came into being fully formed.

“No character was fully formed, but what was fully formed was the outline of the story. The triangle between Aaron, Joni and Sigerius was very clear, the setting was clear, also certain scenes. So it was more like I had this vision of the story that evolved of course during writing.”

Bonita Avenue came out in Holland in 2010. So what has Buwalda been writing since? And is it a little odd to still be talking about these characters still as each edition appears in translation?

“It’s true, I’ve been talking about Bonita Avenue almost every day since 2010. I know those characters’ lives even better than some lives I know for real. I’m writing a new novel, I’m about halfway through and working on it almost every day, but it’s much harder than writing the first one because with the first I lived the life of a recluse. I stepped out of society by quitting the job and nobody needed me, so there is a kind of non-existence when you’re trying to be a writer that makes it very easy to concentrate – there is nothing else to do! But now I’m on the radar and every day somebody asks me something, so it became very hard to find the same focus as I had before.”

The halfway point in the new novel still leaves the finishing line quite a distance away, but this is something he has reckoned quite precisely.

“It will take me another two or three years,” he calculates. “It’s three-and-a-half years since Bonita Avenue was released in Holland, but I lost two complete years in promoting it through its various editions, so I’m about 18 months in.”

The book has been optioned for TV, but he has no wish be directly involved in the production.

“I’m not so interested in making films out of books. The only thing I’ve said was I can’t imagine it as a short film of two hours, so maybe it’s an idea to make a series for television. And they agreed, so that’s what they’re trying to make. I don’t know how long it will take to make it, but they’re serious and they have the option and the rights, so we’ll see.”

There’s a lot of music in the book. Sigerius and Aaron share a liking for jazz, although their knowledge is sometimes lacking or bluffed. Buwalda himself expanded his musical horizons since embarking on the book.

“Halfway through writing Bonita Avenue I discovered classical music. Until I was 37 or 38 I only listened to jazz and pop music, but then I discovered the possibility of writing and listening to classical music at the same time. I started to learn about the composers, then at one point I bought a complete shop! A shop in Dordrecht was closing down, and the guy who owned it put the whole stock on the internet: 3,000 unique CDs for 3,000 euros. I still had 5,000 euros in the bank for the last half-year… and I decided to buy it. Since then I have a complete canonical set of classical music in my house. So in the next novel, classical music plays an important role.”

Joni describes Los Angeles as: “a city that applauded anything and everything as long as it was impermanent, reckless and outrageous.” Buwalda admits he found it easier to describe LA and other American cities from a distance.

“I wasn’t there for long,” he says. “I wrote the chapters before visiting those places, but afterwards I visited them to check and I was there for a month or so – two weeks in Los Angeles and one week in San Francisco and the other week travelling around. I made a lot of notes, then went back to Holland and changed nothing. What I learned from it is it’s possible to visit those places from home, reading the right books, visiting the right websites, picking out the right details – that’s the most important part. When you read a Raymond Chandler novel set in Los Angeles, there are only a few things he mentions about the settings or surroundings. It’s not like reading a Lonely Planet. I even think visiting a place makes it harder to write about it, because the information you have then is too broad, and choosing the right impressions becomes more difficult.”

Bonita Avenue itself is the quiet oasis in San Francisco where the family was briefly functional and happy. The title was chosen to convey a sense of lost hope and nostalgia.

“Exactly, yes. That was the only reason. I think when you look at the timetable of the novel, and the first thing in time you learn about these people is when the Sigerius’s father is interned in a camp on the Burma Railway during the Second World War, and the last thing you know is that Aaron is trying to go to LA and visit Joni in 2008, and between those times the family is happy only in Berkeley between 1980 and 1984 or so, when Tineke and Sigerius’s divorces are in the past, and they have the new nucleus of a family with her two young girls Joni and Janis, and Sigerius is inventing the maths of his life and winning awards. That’s when they were living on Bonita Avenue, and that was the reason to give the novel that name.”

Somebody tore the covers from every book he could get his hands on in every bookstore in Utrecht, Leiden and Zaltbommel without any explanation.”

Soon after publication in Holland, copies of the book were torn and defaced in several bookshops. The media coined the phrase ‘boekenverscheurder’ (literally ‘books tearer’) to describe the incident, and the culprit never explained his actions.

“It was a frightening moment. My publisher called when I was on my way to a reading in a library, and she said somebody ran into a store in Utrecht and tore every copy of Bonita Avenue into pieces. He tore the covers from every book he could get his hands on in every bookstore in Utrecht, Leiden and Zaltbommel. It attracted a lot of attention from the press. The next day I had three camera crews in my house, Twitter exploded, radio shows, et cetera, and it made the guy nervous and regretful so he wrote an anonymous letter to my publisher on a typewriter, and he said he was feeling sick and he regretted what he did, but he didn’t give a motive. Then he made envelopes with 20-euro bills in, the price of one book, so in a shop where he destroyed ten books he put ten twenties in the envelope and in the middle of the night he shoved it under the door without any explanation.”

At the end of the book, it becomes clear that Sigerius is capable of matching the brutality meted out by his son – though at the highest personal cost. But Buwalda sets little store by Freudian ideas that children’s lives and prospects are substantially predetermined by their parents.

“I don’t believe in genes that much, maybe because I only got to know my real father in the last two years. My personal philosophy is that you invent yourself. The biggest thing I took from my youth is that my mother and stepfather worked hard for their children. I won’t forget that, that’s something I like about how they lived. Now I have some wealth because of the success of the novel I still remember the times at home and the real labour my stepfather had to deliver.”

Aaron keeps guinea pigs and hamsters (which – spoiler alert – suffer a rather grisly demise), and I can’t help but ask if Buwalda has himself kept these creatures, and if they make companionable pets.

“Yeah, very,” he grins. “In fact the only character I depicted from reality in the novel is a guinea pig: the guinea pig in my novel is the one I had when I was writing it – though in real life he didn’t come to such a messy end.”

Peter Buwalda has worked as a journalist, an editor at several publishers, and was co-founder of the literary music magazine Wah-Wah. Bonita Avenue was shortlisted for twelve prizes in Holland, going on to win the Academica Prize, the Selexyz Debut Prize, the Tzum Prize, the Anton Wachter Prize and the Leesclubboek van het jaar. It spent two years on the Dutch bestseller lists, and translation rights have been sold to 14 countries. The English edition, translated by Jonathan Reeder, is published by Pushkin Press. Read more.