Petra Hůlová: Gender agendas

by Mark Reynolds

“Wonderfully rough, gloriously evil language.” Die Zeit

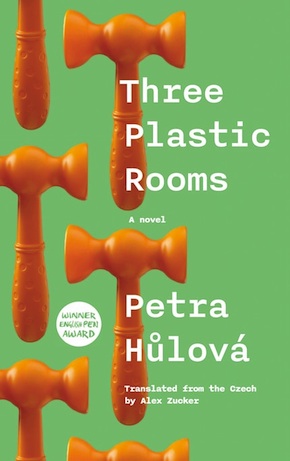

Multiple award-winning Czech novelist and playwright Petra Hůlová’s Three Plastic Rooms takes the form of a foul-mouthed monologue by an unnamed prostitute in city very like Prague, who holds forth on matters regarding her profession, her punters and society at large. It is her second novel to be translated into English, the original Czech edition having first appeared in 2006. I chat to her about revisiting this forthright and endlessly fascinating chronicler of the murkier edges of modern society, and about her wider work.

MR: The narrator of Three Plastic Rooms is a 30-year-old prostitute with strong opinions on everything from desire, exploitation, consumerism, distance and intimacy, to ageing and beauty. Where did her voice spring from?

PH: Although I’ve been to a couple of brothels and I spoke with male friends who shared with me their experiences of visiting prostitutes, it’s based on my own imagination. The attempt was not so much to make a portrait of a streetworker, but rather to approach the topic of sexuality from a different angle. The prostitute as someone who has a profoundly different relationship to sexuality and her body and the body in general was for me a useful tool that helped me to explore certain themes I was interested in.

She came to you quickly; you were writing something else at the time…

Yes, in St Petersburg, where I’d gone out of a romantic idea to write in the city of Dostoevsky. But I came to a dead end when I realised the novel I was trying to write wasn’t really going anywhere. I went out with a can of beer and cigarettes and I was walking along the waterways when I saw a woman on the street and immediately there was this ironic, mocking voice in my head commenting on her. The voice continued on, and I felt I had to go back to my room and start writing. I really let myself be led by that voice. It was a sort of stream of consciousness, but for some time before I had been interested in sexuality as a mirror for gender relations. I knew I wanted to write a novel on that topic, and a female narrator is something I use pretty often in my work.

It was first published over ten years ago. How does it feel to be revisiting it now?

I’ve published eight novels, the ninth will be published this spring, and there are some I appreciate more and some I appreciate less, of course, and this is one of my most favourite. I like to go back to it because still nowadays I feed on the same mix of emotions and thoughts. My last novel, The Gorge, which was published three years ago, is again a monologue. It’s my most autobiographical book because it’s a writer who narrates the story, but it’s kind of self-mocking as the writer is very egocentric and she hates her kids because she sees them only as an obstacle to her writing, which she does basically just for money. She’s a very dislikable character, but the topics of gender and sexuality and a kind of self-hatred are still present. And my next book that is about to be published is a feminist dystopia, and again gender and sexuality are very much there. So I think Three Plastic Rooms is like a starting point of certain tendencies that I developed further, and are still very vivid and alive for me.

It was the director’s idea to divide the voice into five characters. I thought it was a great approach and it was a great pleasure to hear the characters speaking on the stage. It was also my first encounter with theatre.”

How closely did you work with Alex Zucker on the translation, and how did he go about matching the very careful and inventive language of the original?

Well, I think Alex is the best translator of contemporary Czech literature into English. The art of translation is to be able to keep the content and the meaning yet make it understandable in other contexts of language and culture, and I trust him immensely to do that. He translated my first novel All This Belongs to Me some years ago, and he was working pretty independently and I didn’t feel I had to check on anything very much. He just had some concrete questions; I think especially there are some words in the text that I invented like the names for sexual organs, where I played with gender as well to change the meaning and the power structure of sexual activity.

Three Plastic Rooms was made into a stage play, in which the narrator’s personality was split into five distinct voices played by different actors. How did that come about?

It was the director Viktorie Čermáková’s idea to divide the voice into five characters. She made some cuts in the text, of course, because it’s too long for a play, but she didn’t make any changes; she basically attached pieces of text to particular characters that she defined as certain variations of the voice. Because the narrator is pretty ambiguous: sometimes she is romantic, sometimes she is vulgar, there are moments she reflects in a philosophical way on contemporary society, there are moments she reflects on her clients, whatever. I thought it was a great approach and it was a great pleasure to hear the characters speaking on the stage. It was also my first encounter with theatre. Later I started to write theatre plays myself.

Can you say a little about the plays you’ve subsequently written?

After I was asked to adapt Ian McEwan’s Atonement for the Švandovo Theatre in Prague, I wrote three other plays. The topic of Cell Number is Czech identity: what does it mean and where are we going? Then I adapted The Gorge together with the director Kamila Polívková. For my latest play, which will be performed in the spring, I was approached again by Viktorie Čermáková to adapt another novel of mine. She left it up to me what I would choose, and I chose The Guardians of the Public Good, which is told by a young communist who reflects critically on the changes in 1989; so it’s also quite political. But I didn’t want just to adapt it, I wanted to set in in the present, so the character in the book who was in her early 20s commenting on the start of capitalism in my country is now in her 40s, reflecting on all that’s happened since then.

All This Belongs to Me, about three generations of women in Mongolia, came out when your were just 23 and was a huge success. What drew you to Mongolia in the first place, and how did that story come together?

I was on a Cultural Studies course and I saw a documentary by Nikita Mikhalkov called Urga, and I just fell in love with the place and instantly knew I wanted to go there to study the ethnography and learn the language. Part of the curriculum is one year at the National University in Ulan Bator, and I went there with five fellow students from my class. It was difficult there in Mongolia in 2000, a completely different culture and winter and I had a lot of free time, so writing became my shelter and I started working on fiction there. I didn’t have a laptop with me so I was writing by hand, and then I came back home and started rewriting the story on the computer. But in the process of rewriting it, I realised it was not worth pursuing, so I started working on a different thing from scratch, and that ended up as All This Belongs to Me. As it often is with debuts, it was very spontaneous, intuitive writing. I just imagined I was a Mongolian woman, and tried to describe the world through her eyes. I see today what a dubious ambition that was, but at that time I just jumped into it, and as soon as I finished her narration I thought, there is more in this story of her family, let’s try to speak through the character of her mum. Oh, and there’s more, why don’t I try to show the perspective of her granny? And so it became the perspectives of five women from one family, on family affairs and a discussion of tradition and modernity in Mongolia. Nowadays I see it as a very problematic project: how could I dare to do this? What would I think if, I don’t know, a guy from Japan came to Prague for one year and then wrote a novel about being a Czech? There were critics in my country who took it as a hidden narrative on the topic of post-revolution changes in the Czech Republic, so people interpret it in different ways, but for many people it was I think a persuasive description of a place they’d never been to. I think I grasped something universal, and it does tell you something about the place. It’s an amazing culture and I speak the language and have a certain insight into the place and the mentality, but it was a very courageous act and I wouldn’t be able to do anything like that anymore. But I was 21 and I didn’t bother myself with all these side thoughts.

You mentioned the upcoming ‘feminist dystopia’; could you say some more about that?

The working title is A Brief History of The Movement, and it’s a story from the near future when radical feminism takes over society and becomes the mainstream. To sum up the ideology, they emphasise that woman is a human being that should be valued for her inner qualities, her spirit and character, and not for her attractiveness, so it is forbidden to be attracted to a woman on the basis of her body and appearance, you are only allowed to be attracted to her on the basis of her true human qualities. Most males have learned how to change their attitudes, yet still about ten per cent of men don’t, and illegally they enjoy pornography and just won’t accept the ideology, so they are interned in institutions for re-education. The book is narrated by a guard/lecturer at one of these institutions, and she describes how the movement started and how the institution operates, and then she goes on a work trip to an institution for females – because also there are women who go for illegal plastic surgery and use make-up and just won’t give up the old manipulative female strategies based on appearance. So you follow the narration of this guard who works passionately for the movement, and she tells you about this brand new happy world from the position of the prevailing mainstream, and she believes they are near to a final victory in which everybody accepts the new ideology. So it’s not told as dystopias often are from the perspective of an oppressed outsider, but by a representative of the winning majority. I enjoyed writing it very much. I was working on it for many years because the first attempt, the first version of the novel, was completely different with a male narrator who agrees with the new rules and has to send his best friend for re-education. It really took me a long time, but I think I grasped something pretty essential relating to our problems with gender equality and political correctness. I’m not laughing at the system, I think there is great value in the idealism in there, and I don’t like the fact that appearance and youth is much more important for women than for men and I think it’s unfair. But this system would be problematic and one can hardly agree with everything that happens in the institutions. But it’s ambiguous and that was my aim, to just make you think about it and get you out of your comfort zone.

Who are your literary heroes or major influences?

Well, definitely when I was younger, writers I adored a lot, and I still respect them a great deal, were Kafka and Kundera, and then I think later my most favourite writer for many years was and still is Elfriede Jelinek, the Austrian Nobel Prize winner. In the preface to Three Plastic Rooms, Peter Zusi relates my novel to Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own. I wasn’t thinking about it when I was writing the novel but Virginia Woolf was from my early childhood very much present in my intellectual life because she was and is my mum’s favourite author, so my mum was literally stuffing me with Virginia Woolf’s books from an early age. I kind of didn’t like it because the books were too difficult, but then later I fell in love with her work sincerely. I even remember I cut out one short story from a book we had at home and sent it in an envelope to my first boyfriend as a gift of love. So yes, Virginia Woolf was definitely an important author for me as well.

And which other Czech writers are doing interesting things right now?

Right now the writer I follow most closely is David Zábranský. I really like his work, and we support each other as writers who share an ambition to be present not only in their writing but also to have a public voice. Among other writers I would mention Jáchym Topol or Emil Hakl.

I don’t doubt the revolution was a very positive change in Czech society, but no one was shouting for capitalism on the demonstrations, and Václav Havel was very critical of both communism and capitalism in his work.”

You were still a child at the time of the Velvet Revolution. What are your personal memories of communist rule and the subsequent reforms?

I’m very grateful that I still remember communist times. I’m from the last generation that has those memories. I was ten years old when the revolution happened, and it really gives me an opportunity to compare today’s world with one that younger people really don’t grasp. I have many memories of grey streets and simple stores and communist teachers at school. What I remember very well is the confusion I felt during the revolution because even though I come from, let’s say, an intellectual family, my parents never spoke to me about politics and were not dissidents in any way. And then I experienced them being very enthusiastic and happy about the revolution, and I thought, Why? You’re now happy that the situation is changing, but you never told me anything was wrong before! So I felt a little cheated and confused. I was not really able to articulate it this way, but I felt a kind of disappointment in my parents who up to that point were just people I completely respected and adored as a kid. I don’t want to doubt the revolution was a very positive change in Czech society, but at first people were yearning for freedom and democracy and not capitalism – no one was shouting for capitalism on the demonstrations, and Václav Havel was very critical of both communism and capitalism in his work. But then it just changed, and for many years basically any criticism of the right-wing political establishment was taboo, and anybody who did it was muted by the argument that it might not be perfect, but it’s better than what we had, and that really had a very negative effect on the development of my country, both in terms of society and thinking. And intellectuals let it happen, let themselves be castrated by this argument. Fortunately nowadays it’s changing, and leaning to the left does not automatically make you a communist villain who should just shut up, it’s again becoming a respected position – but it was a long process.

Petra Hůlová’s novels, plays, and screenplays have won numerous awards, and she is a regular commentator on current events for the Czech press. She studied language, culture and anthropology at universities in Prague, Ulan Bator and New York, and was a Fulbright scholar in the USA. Her eight novels and two plays have been translated into more than ten languages. Three Plastic Rooms is out now in paperback from Jantar Publishing, translated by Alex Zucker.

Petra Hůlová’s novels, plays, and screenplays have won numerous awards, and she is a regular commentator on current events for the Czech press. She studied language, culture and anthropology at universities in Prague, Ulan Bator and New York, and was a Fulbright scholar in the USA. Her eight novels and two plays have been translated into more than ten languages. Three Plastic Rooms is out now in paperback from Jantar Publishing, translated by Alex Zucker.

Read more

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.

@bookanista