Rumaan Alam: This is how civilisation ends

by Farhana Gani

“The novel excels in its dissection of modern liberal America and forces the reader to confront the limits of their own heroism in the face of disaster.” Financial Times

“I woke up this morning and the world already feels safer!” declared a friend on Facebook the day after Joe Biden and Kamala Harris swept to victory in the US election. Hah! Wait till you read Leave the World Behind, I thought, perhaps a little too sceptically, you’ll soon change your tune.

If this suggests Rumaan Alam’s latest novel is to be avoided, you’ll be doing yourself a great disservice and missing out on a thrilling and unnerving critique of modern times. His book is as brilliant as it is damning; and as entertaining as it is disturbing. Already highly praised on both sides of the Atlantic, this is a tautly written tale about the way we live now, spanning a few days in the lives of people like you and me, and set in the present day – Angela Merkel leads Germany and the 45th President is dividing the nation.

Like Joel Edgerton’s equally unsettling contagion horror film It Comes at Night, Alam has created a world within a world, in which bewildering events force two families together, and each tries to protect what’s theirs as fear and distrust grows. Something even bigger is going on all around but our protagonists have no idea what it is or how bad it is going to get.

Amanda and Clay are a successful, highly-educated, comfortably-off, happily married 40-something couple with two bright, well-mannered teenagers – Rose and Archie. The family are staycationing in Long Island not too far from their apartment in Manhattan. Amanda arranged their luxurious Airbnb via email, and for the adults it’s an opportunity to “pantomime ownership for a week” and leave the trappings of their busy lives behind for the sun-filled solace of the Hamptons.

Armed with books, swimming apparel and bag-loads of gourmet food, they begin to unwind and spend quality time together. Throughout these introductory chapters Alam paints a picture of a family that gets on well, secure in their future together and at ease with themselves. He also masterfully weaves in their middle-class affluence, frustrations and aspirations, their consume-and-discard culture and their cognitive dissonance about environmental issues. A trip to the beach hints at changes in the weather systems; there is “detritus washed up on the sand, shells and plastic cups and iridescent balloons that had celebrated proms and sweet sixteen miles away.”

All is calm, the weather is good, the food plentiful and everyone is getting on… until one night, after the kids have gone to bed, there is a knock at the door.

Into their blissful isolation, a mere 40-pages in, arrive the Washingtons, Ruth and George. Unannounced. They’re stressed and dishevelled. They’ve managed to escape New York, where something terrible is happening. They can’t say what, but there’s a city-wide power cut, and their phones aren’t working. The safest place they could think of was their house in the country. Clay is courteous and calm, but Amanda’s hackles are raised: “This didn’t seem to her like the sort of house where black people lived.”

If you found the US election result exhilarating, try to imagine the reverse of that feeling and you’ve got the creeping horror of unfolding dread-laden events seeping into your soul as you turn the pages.”

This sets the scene for the rest of the novel. As the mystery deepens, life becomes claustrophobic for both families trying hard to tolerate each other under one roof as they endeavour to find out what is going on. WiFi is down, no TV channels are on air. Clay fruitlessly tries to go to the nearest village for news. Then comes the sound. It’s a blast through the air like nothing they’ve ever heard before. It shatters windowpanes and shakes them to the core. What is it?

Whilst the families are none the wiser about events unfolding in the wider world, Alam cleverly peppers the narrative with enough clues for the reader to piece the horrors together to see a not too far-fetched scenario of how civilisation ends. People are dying; refugee camps are overflowing; animals are behaving erratically; ICUs kill instead of heal when the power is cut; commuters on public transport or workers in skyscrapers are trapped; food is in short supply; garbage is piling up on the streets… it’s a catastrophe of global proportions.

Netflix has snapped up the film rights, and Julia Roberts and Denzel Washington are signed up to play Amanda and George. Alam wrote the novel two years before the Covid pandemic and the escalation of the #BlackLivesMatter protests, and now we are better versed in how governments respond and individuals behave during a global catastrophe, it will be interesting to see how the adaptation further reflects our times.

If you found the US election result exhilarating, try to imagine the reverse of that feeling and you’ve got the creeping horror of unfolding dread-laden events seeping into your soul as you turn the pages. You might also consider that on the day Biden was confirmed as President-elect, in Denmark 17 million mink were quietly sentenced to death when a few were found to be Covid carriers. Leave the World Behind is a novel signalling the shape of things to come. I implore you to read it.

I caught up with Rumaan Alam to discuss his grim vision of the future and why it strikes a contemporary chord.

Farhana: Your book couldn’t be more timely. When did you start working on it, and what sparked the idea?

Rumaan: The first spark of the idea came at the end of 2017 – it was winter, and I was reminiscing about our family holiday that summer, in a house we’d rented via Airbnb that’s almost precisely the house I describe in the novel. But things evolved from there; the desire was not to tell the story of my own vacation, but something else entirely. I wanted to write a novel of family life and the small details of domesticity that explored the big issues of our day.

It draws on events raging at the heart of the Western world right now – the pandemic; climate change; and the #BlackLivesMatter movement. It is set in the present day: “The 45th president of the United States seemed to have dementia. Angela Merkel seemed to have Parkinson’s disease. Ebola was back…” Why did you want to set it during Trump’s tenure?

I didn’t want this to be a book about Trump; one of the frustrations of sharing the planet with him is the way he’s forced us to see everything as somehow related to him. So I avoid saying his name, but he’s there, because I wanted this to be a book about this moment. Not to talk about that guy, but to talk about what’s most urgent right now.

How did you and your family live during the lockdown? Were you able to write? Did you develop new habits and coping behaviours?

I’ve not been writing much but then I probably wouldn’t have been coming right off of this new book. Writing is an input/output situation, and I need time to sort of regroup and figure out what it is I want to be tackling next. One of the frustrations of this moment is that the way I find my way forward is by looking at art – going to museums, seeing films, hearing music, even just being out in the world. All the things we mostly can’t be doing now! My family as so many others saw life get smaller, but so be it; we have a nice home, I have the luxury of working from home, and so we simply made do, trying to improvise school for the kids and stay entertained here. That said, the one art these conditions haven’t taken from us is the book. So I’ve been reading, which has always been my greatest comfort.

Was the community spirit evident in your neighbourhood? In your novel when George goes to seek help from Danny, his builder, neighbourliness is sacrificed and it becomes each man for himself. What does it take for humans to lose their humanity?

I have found it a great comfort to be right here in New York City. We’ve seen community fridges pop up so that our neighbors dealing with food scarcity have a resource down the street; we’ve seen people put on masks and do their best to observe what makes most sense. It’s very reassuring. But history has shown us so many examples of people failing to make the moral choice; the citizens who stood by during great injustice. Maybe I’m one of those people too. There’s terrible injustice in this country at this moment, and maybe my disagreeing with our policies at the border, say, isn’t enough. Maybe we humans shouldn’t take our own humanity on faith; maybe we all fail to live up to it.

Has the Covid-19 response changed your views for better or worse on how governments and the public at large are capable of responding to a crisis?

I believe we’ve seen the complete abdication of responsibility by our government. It’s indefensible, it’s absurd, it’s maddening. I have faith in the public but mourn that we have so degraded our civic institutions. I hope we can see this culture’s attitude change; we should demand a government that takes an active role and not a passive one.

Under lockdown there was much in the news about wildlife reclaiming the streets; the skies becoming quiet; people having epiphanies about material goods not being anywhere as important as health, food, each other. This is also central in the novel. Do Americans (and Europeans) need to reconfigure their priorities?

I cannot speak for others but I can acknowledge my own complicity here. Money won’t save us. Things won’t save us. We’ve failed our moral responsibility to be stewards of this planet. I hope this epiphany arrives, and I hope it leads to change.

Amanda and Clay, both well educated, are nonetheless driven by status and wealth envy. “Clay had tenure, and Amanda had the title of director, but they did not have level floors and central air-conditioning.” Are we living in anti-intellectual times?

I don’t know if the impulse toward material comfort and status is anti-intellectual but it does feel real, and rampant.

You reference Six Degrees of Separation, a play about a wealthy New York couple bending over backwards to welcome into their home a man posing as Sidney Poitier’s son. And of course, Poitier is famed for starring in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner. How much influence did these works have in shaping your characters?

I did think a lot about works for the stage – both John Guare’s masterpiece and Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, the former for the way it toys with race and our expectations about how stories about race must play out and the latter for the way it shows the menace lurking beneath the conviviality of strangers thrust together, drinking and talking. Seeing a play, the audience can feel trapped with the characters. I wanted that kind of experience for the reader, that you feel trapped inside the house as they are.

The racial tension in the novel is fascinating. Can Amanda’s initial attitude towards the Washingtons be justified in any way? After all, she’s only a product of an upbringing, education and political system that sees the world through a white lens… Do you think many readers will see themselves in Amanda?

How might Amanda herself justify her uglier thoughts – that she’s afraid for her children? That feels defensible! But of course we know that her suspicions are about more than protecting the kids. Indeed, she is just a product of a society but perhaps should push herself to be better or more enlightened. I hope readers find themselves discomfited; I hope they ask themselves why.

Seeing a play, the audience can feel trapped with the characters. I wanted that kind of experience for the reader, that you feel trapped inside the house as they are.”

You give us the measure of Clay when he gets lost on his way to the grocery store and encounters a distressed woman, unable to speak English. He hides this event from the others but it’s an action that will haunt him. What does this reveal about “masculine responsibility” today?

I’m not sure I believe in seeing the world in terms of masculine or feminine, but Clay does – he sees it as his role as a man and a father to be the protector, the problem-solver. But he’s not equal to the task. He fails a pretty big moral test by declining to help a woman in need. What does that say about his handle on masculine responsibility; has he failed to be a man or failed to be a human?

Animals feature extensively in the book. Why was animal symbolism important to you?

Animals are important in myth and folklore from every culture. I personally find them uncomfortably inscrutable; my discomfort with animals imbues them, I think, with a feeling of mystery. There’s a sense that if the people in the book could understand what the animals were up to they would know how to proceed. But people can never really understand animals, I don’t think.

It’s being adapted for Netflix, with Denzel Washington and Julia Roberts onboard. Did you write the novel with these two actors in mind? (You have Amanda say to George at one point, “You know, you look a little like Denzel Washington.” – and “it was not the first time he’s heard this”. Was this dialogue in your original manuscript, or was it a cheeky addition after Denzel had signed up to play the role? And do you expect the line to be retained in the adaptation?)

No, that line was part of the original manuscript, so the involvement of Washington himself is just one of those odd and unforeseeable things, the happiest of accidents. I did not ever imagine this book being adapted for film but am thrilled that it will be. I do wonder how Sam Esmail, the writer and director, will deal with that line, but that’s his call!

How involved are you in the adaptation?

That work is in the hands of an expert – Sam Esmail!

“Trees marked their lives in rings that can’t be seen; people, in the garbage they left everywhere.” Your book left this reader deeply unsettled about the way the world is heading and the future of the planet. Will this pandemic change our lifestyle in any way? What paradigm shift do you hope for, for future generations?

I don’t know how to answer this question. I’m not sure if the pandemic will be the thing to change our attitude toward global climate change; I’m not sure what will.

Towards the end of the novel George reflects on a “failure of imagination”, realising that the evidence was apparent in the death of trees, catastrophic rise in animal extinctions, perilous journeys undertaken by desperate migrants and refugees. Do you see a failure of imagination in world leadership today, and how responsible is the individual?

I absolutely do. Our leadership, as so many of the rest of us, is hostage to capital and power and unwilling or unable to rise to the challenges of the moment. I have a sense of what our leaders might do; I’m not sure what the rest of us ought to do.

Which is your go-to source for trusted, factually-correct news?

The New York Times.

Clay kids himself that smoking is a patriotic act (“like owning slaves or killing the Cherokee”). What present-day acts of patriotism trouble you?

There’s a prevailing idea that certain things are American and others are not; this troubles me. To speak of anything as being un-American feels maddening, counter to the whole experiment of this country.

Are you working on your next novel, and are you willing to share anything at this stage?

It’s too soon to talk about!

Are there any books you’ve read in recent months you’d particularly recommend?

I’ve read a lot that’s great this year – Ayad Akhtar’s Homeland Elegies, Lydia Millet’s A Children’s Bible, Hiroko Oyamada’s The Hole, Bryan Washington’s Memorial. And this is only to mention books published this year. No one who’s really looking can say there’s a shortage of good things to read.

As the year edges to a close, how would you define 2020 for yourself, for America and for the world?

Precipitous.

Rumaan Alam is the author of three novels: Rich and Pretty, That Kind of Mother and Leave the World Behind. His other writing has appeared in The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, New York Magazine, Buzzfeed, and The New Republic, where he is a contributing editor. He also co-hosts two podcasts for Slate. He studied writing at Oberlin College, and now lives in New York with his husband and two kids. Leave the World Behind is published in hardback and eBook by Bloomsbury.

Rumaan Alam is the author of three novels: Rich and Pretty, That Kind of Mother and Leave the World Behind. His other writing has appeared in The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, New York Magazine, Buzzfeed, and The New Republic, where he is a contributing editor. He also co-hosts two podcasts for Slate. He studied writing at Oberlin College, and now lives in New York with his husband and two kids. Leave the World Behind is published in hardback and eBook by Bloomsbury.

Read more

rumaanalam.com

@Rumaan

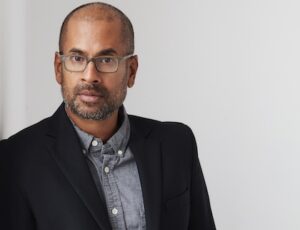

Author portrait © David A. Land

Farhana Gani is a freelance writer and a founding editor of Bookanista.

@farhanagani11

@bookanista

wearebookanista

bookanista.com/author/farhana/